1994 Northridge earthquake

Buildings collapsed as a result of the earthquake | |

Los Angeles Las Vegas | |

| Date | January 17, 1994 |

|---|---|

| Origin time | 4:30:55 a.m. PST[1] |

| Duration | 10–20 seconds[2] |

| Magnitude | 6.7 Mw |

| Depth | 11.4 mi (18.3 km) |

| Epicenter | 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°WCoordinates: 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°W |

| Type | Blind thrust |

| Areas affected |

Greater Los Angeles Area Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $13–$44 billion[3] |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent)[1] |

| Peak acceleration | 1.82g horizontal[4] |

| Casualties |

57 killed > 8,700 injured |

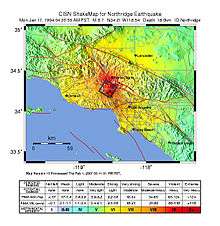

The 1994 Northridge earthquake occurred on January 17, at 4:30:55 a.m. PST and had its epicenter in Reseda, a neighborhood in the north-central San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, California. It had a duration of approximately 10–20 seconds. The blind thrust earthquake had a moment magnitude (Mw) of 6.7, which produced ground acceleration that was the highest ever instrumentally recorded in an urban area in North America,[5] measuring 1.8g (16.7 m/s2)[6] with strong ground motion felt as far away as Las Vegas, Nevada, about 220 miles (360 km) from the epicenter. The peak ground velocity at the Rinaldi Receiving Station was 183 cm/s[7] (4.09 mph or 6.59 km/h), the fastest peak ground velocity ever recorded. In addition, two 6.0 Mw aftershocks occurred, the first about one minute after the initial event and the second approximately 11 hours later, the strongest of several thousand aftershocks in all.[8] The death toll was 57, with more than 8,700 injured. In addition, property damage was estimated to be between $13 and $40 billion, making it one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history.

Epicenter

The earthquake struck in the San Fernando Valley about 20 miles (31 km) northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Although given the name "Northridge", the epicenter was located in the community of Reseda; it took several days to pinpoint the epicenter in detail. This was the first instance with a hypocenter directly beneath a U.S. city since the 1933 Long Beach earthquake.[9]

The National Geophysical Data Center placed the hypocenter's geographical coordinates at 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.21306°N 118.53694°W and at a depth of 11.4 miles (18.3 km).[10] It occurred on a previously undiscovered fault, now named the Northridge blind thrust fault (also known as the Pico thrust fault).[11] Several other faults experienced minor rupture during the main shock and other ruptures occurred during large aftershocks, or triggered events.[12]

Damage and fatalities

Damage occurred up to 85 miles (125 km) away, with the most damage in the west San Fernando Valley, and the cities of Santa Monica, Simi Valley and Santa Clarita. The exact number of fatalities is unknown, with sources estimating it at 60[1] or "over 60",[13] to 72,[14] where most estimates fall around 60.[15] The "official" death toll was placed at 57;[14] 33 people died immediately or within a few days from injuries sustained,[16] and many died from indirect causes, such as stress-induced cardiac events.[17][18] Some counts factor in related events such as a man's suicide possibly inspired by the loss of his business in the disaster.[14] More than 8,700 were injured including 1,600 who required hospitalization.[19]

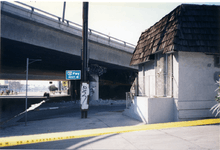

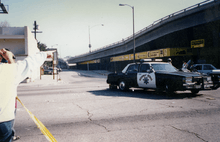

The Northridge Meadows apartment complex was one of the well-known affected areas in which sixteen people were killed as a result of the building's collapse. The Northridge Fashion Center and California State University, Northridge also sustained very heavy damage—most notably, the collapse of parking structures. The earthquake also gained worldwide attention because of damage to the vast freeway network, which serves millions of commuters every day. The most notable of this damage was to the Santa Monica Freeway, Interstate 10, known as the busiest freeway in the United States, congesting nearby surface roads for three months while the freeway was repaired. Farther north, the Newhall Pass interchange of Interstate 5 (the Golden State Freeway) and State Route 14 (the Antelope Valley Freeway) collapsed as it had 23 years earlier in the 1971 Sylmar earthquake even though it had been rebuilt with minor improvements to the structural components.[20] One life was lost in the Newhall Pass interchange collapse: LAPD motorcycle officer Clarence Wayne Dean fell 40 feet from the damaged connector from southbound 14 to southbound I-5 along with his motorcycle. Because of the early morning darkness, he likely did not realize that the elevated roadway below him had collapsed, and was unable to stop in time to miss the fall and died instantly. When the interchange was rebuilt again one year later, it was renamed the Clarence Wayne Dean Memorial Interchange in his honor.

Additional damage occurred about 50 miles (80 km) southeast in Anaheim as the scoreboard at Anaheim Stadium collapsed onto several hundred seats. The stadium was vacant at the time. Although several commercial buildings also collapsed, loss of life was minimized because of the early morning hour of the quake, and because it also occurred on a federal holiday (Martin Luther King, Jr. Day). Also, because of known seismic activity in California, area building codes dictate that buildings incorporate structural design intended to withstand earthquakes. However, the damage caused revealed that some structural specifications did not perform as intended. Because of these revelations, building codes were revised. Some structures were not red-tagged until months later, because damage was not immediately evident.

The quake produced unusually strong ground accelerations in the range of 1.0 g. Damage was also caused by fire and landslides. The Northridge earthquake was notable for hitting almost the same exact area as the MW 6.6 San Fernando (Sylmar) earthquake. Estimates of total damage range between $13 and $40 billion.[21]

Most casualties and damage occurred in multi-story wood frame buildings (e.g. the three-story Northridge Meadows apartment building). In particular, buildings with an unstable first floor (such as those with parking areas on the bottom) performed poorly. Numerous fires were also caused by broken gas lines from houses shifting off their foundations or unsecured water heaters tumbling.[22] In the San Fernando Valley, several underground gas and water lines were severed, resulting in some streets experiencing simultaneous fires and floods. Damage to the system resulted in water pressure dropping to zero in some areas; this predictably affected success in fighting subsequent fires. Five days later, it was estimated that between 40,000 and 60,000 customers were still without public water service.[23] As expected, unreinforced masonry buildings and houses on steep slopes suffered damage. However, school buildings (K-12), which are required by California law to be reinforced, in general survived fairly well.

Valley fever outbreak

An unusual effect of the Northridge earthquake was an outbreak of coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) in Ventura County. This respiratory disease is caused by inhaling airborne spores of fungus. The 203 cases reported, of which three resulted in fatalities, was roughly 10 times the normal rate in the initial eight weeks. This was the first report of such an outbreak following an earthquake and it is believed that the spores were carried in large clouds of dust created by seismically triggered landslides. Most of the cases occurred immediately downwind of the landslides.[24]

Hospitals affected

Eleven hospitals suffered structural damage and were damaged or rendered unusable.[19] Not only were they unable to serve their local neighborhoods, but they also had to transfer out their inpatient populations, which further increased the burden on nearby hospitals that were still operational. As a result, the state legislature passed a law requiring all hospitals in California to ensure that their acute care units and emergency rooms would be in earthquake-resistant buildings by January 1, 2005. Most were unable to meet this deadline and only managed to achieve compliance in 2008 or 2009.[25]

Television, movie, and music productions affected

The production of movies and TV shows was disrupted. The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Profit and Loss" was being filmed at the time, and actors Armin Shimerman and Edward Wiley left the Paramount Pictures lot in full Ferengi and Cardassian makeup respectively.[26] The season five episode of Seinfeld entitled "The Pie" was due to begin shooting on January 17 before stage sets were damaged. NBC's The Tonight Show, hosted by Jay Leno, took place in the NBC Studios in Burbank, close to the epicenter of the quake. Also, ABC's General Hospital, which shoots in Los Angeles, was heavily affected. The set, which is at ABC Television Center, suffered major damage including partial structural collapse and water damage.

All of the earthquake sequences in the Wes Craven film New Nightmare were filmed a month prior to the Northridge quake. The real quake struck only weeks before filming was completed. Subsequently, a team was sent out to film footage of the quake damaged areas of the city. The cast and crew had initially thought that the scenes that were filmed before the real quake struck were a bit overdone, but upon viewing the footage after the earthquake, they were reportedly startled by the realism of it.[27]

Some archives of film and entertainment programming were also affected. For example, the original 35 mm master films for the 1960s sitcom My Living Doll were destroyed.[28]

The first and second episodes of the fifth season of Baywatch featured the earthquake, and how the lifeguards responded to it, professionally and personally.

Transportation affected

Portions of a number of major roads and freeways, including Interstate 10 over La Cienega Boulevard, and the interchanges of Interstate 5 with California State Route 14, 118, and Interstate 210, were closed because of structural failure or collapse. James E. Roberts was chief bridge engineer with Caltrans and was placed in charge of the seismic retrofit program for Caltrans until his death in 2006.

Rail service was briefly interrupted, with full Amtrak and expanded Metrolink service resuming in stages in the days after the quake. Metrolink used the interruptions to road transport as a reason to experiment with service to Camarillo and Oxnard, which continues to the present. During the interruption, Metrolink leased equipment from Amtrak, San Francisco's Caltrain and Toronto, Canada's GO Transit to handle the sudden onslaught of passengers. All MTA bus lines operated service with detours and delays on the day of the quake. Los Angeles International Airport and other airports in the area were also shut down as a 2-hour precaution, including Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport (now Bob Hope Airport) and Van Nuys Airport, which is near the epicenter, where the control tower suffered from radar failure and panel collapse. The airport was reopened in stages after the quake.

Universities, colleges, and schools affected

California State University, Northridge was the closest university to the epicenter. As such, many campus buildings were heavily damaged and a parking structure collapsed; as a result, many classes were moved to temporary structures. In Valencia, California Institute of the Arts also experienced heavy damage and classes were relocated to a nearby Lockheed test facility for the remainder of 1994. Los Angeles Unified School District closed local schools throughout the area, schools reopened one week later. University of California, Los Angeles and other universities were also shut down. The University of Southern California suffered some structural damage to several older campus buildings, but classes were conducted as scheduled.

Entertainment and sports affected

Universal Studios Hollywood shut down the Earthquake attraction, based on the 1974 motion picture blockbuster, Earthquake. It was closed for the second time since the Loma Prieta earthquake. Angel Stadium of Anaheim (then known as Anaheim Stadium), which is far away from the epicenter, suffered some damage when the scoreboard fell into the seats. The theme parks Disneyland, Knott's Berry Farm and Six Flags Magic Mountain were shut down after the quake, but only for inspections, since all were designed with earthquakes in mind. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena suffered minor damage. The major Hollywood film studios including Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, Columbia Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Walt Disney Studios and Universal Studios were also shut down. The recording venues Capitol Records and Warner Bros. Records were shut down at the time of the quake, most notably Madonna's Bedtime Stories and Ill Communication by Beastie Boys.

The Los Angeles Clippers of the NBA had three home games postponed or moved to other venues. The game scheduled against the Sacramento Kings was postponed, the game against the Cleveland Cavaliers was relocated to The Forum (then the home arena of the Los Angeles Lakers), and the game against the New York Knicks was moved to the Arrowhead Pond (now Honda Center) in Anaheim.

Other buildings affected

Numerous Los Angeles museums, including the Art Deco Building in Hollywood, were closed, as were numerous city shopping malls. Gazzarri's nightclub suffered irreparable damage and had to be torn down. The city of Santa Monica suffered significant damage. Many multifamily apartment buildings in Santa Monica were yellow-tagged and some red-tagged. Especially hard hit was a rough line between Santa Monica Canyon and Saint John's Hospital. Along this rough linear corridor was a significant amount of damage to property. The City of Santa Monica provided assistance to landlords dealing with repairs so tenants could return home as soon as possible.

Radio and television affected

Los Angeles' radio and television stations were knocked off the air, but resumed coverage later.

NBC affiliate KNBC was the first television station to go on the air[29] while reporters and anchors Kent Shocknek, Colleen Williams and Chuck Henry were producing special reports throughout the morning. Other stations KTLA, KCAL, KCBS and KABC were also knocked off the air. Afterward, anchors and reporters Stan Chambers and Hal Fishman of KTLA, Laura Diaz and Harold Greene of KABC, John Beard of KTTV, and Tritia Toyota of KCBS were doing coverage throughout the morning.

Radio stations such as KFI, KFWB and KNX were on the air during the main tremor, causing severe static on the airwaves. KROQ-FM's Kevin and Bean morning show asked those people tuned in to stay out of their homes. Mark & Brian's morning show on KLOS was also affected. The duo spoke to Los Angeles-area residents about their situation.

FM radio stations such as KRTH, KIIS-FM, KOST-FM and KCBS-FM were bringing special reports when morning show hosts Robert W. Morgan, Rick Dees and Charlie Tuna were calling Los Angeles residents and others from their sister stations to bring their belongings to the stations and advising people not to drink water.

Government and organization affected

The United States Postal Service suspended all mail service throughout the Los Angeles area for several days. The Los Angeles Public Library shut down most of its branches; books were knocked down after the quake. The Los Angeles City Hall suffered no damage. Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan declared a state of emergency and issued curfews in the area, while Governor Pete Wilson and President Bill Clinton visited Los Angeles to tour the area. The Archdiocese of Los Angeles's Cathedral of St. Vibiana suffered severe damage and canceled activities until a new cathedral was built in 2002. The Church on the Way, which is near the epicenter, suffered some damage to the church campus building. The Martin Luther King Jr. Parade, scheduled to take place on January 17, was not held.

Legislative changes

The Northridge earthquake led to a number of legislative changes. Due to the large amount lost by insurance companies, most insurance companies either stopped offering or severely restricted earthquake insurance in California. In response, the California Legislature created the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), which is a publicly managed but privately funded organization that offers minimal coverage.[30] A substantial effort was also made to reinforce freeway bridges against seismic shaking, and a law requiring water heaters to be properly strapped was passed in 1995.

Building code changes

With each major earthquake comes new understanding of the way in which buildings respond to them. Advances in the technology associated with testing systems, design and seismic modeling software, structural connections, structural forms, and seismic force resisting systems have accelerated dramatically since Northridge. There is an array of building forms and systems that are no longer legal to build. An example is the previously popular "soft-story" multifamily apartments. These buildings typically look like a three-story box on a narrow lot, where the upper two floors overhang the lower floor and are supported on pipe columns so cars can be parked underneath. Because the ground level is soft relative to the upper floors the upper portion can sway and fall onto the carport below. Today, no wood floors are allowed to extend more than an additional 15% beyond the shear wall or other lateral-load resisting element of the floor below. This typically results in overhangs of only up to three or four feet, compared to the 20 to 40 feet that was previously built. If an architect still wants this type of design, the structural engineer may specify that the previously used pipe column design be replaced with a laterally stiff steel "moment frame." This can also mitigate the problem of the soft-story structure by stiffening the soft ground floor.

See also

- 2008 California earthquake study

- List of earthquakes in California

- List of earthquakes in the United States

References

- 1 2 3 "Historic Earthquakes". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Introduction". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Petak, William; Elahi, Shirin (2001). The Northridge Earthquake, USA and its Economic and Social Impacts (PDF). EuroConference on Global Change and Catastrophe Risk Management Earthquake Risks in Europe, IIASA, Laxenburg Austria, July 6–9, 2000. p. 5.

- ↑ Yegian, M.K.; Ghahraman; Gazetas, G.; Dakoulas, P.; Makris, N. (April 1995). "The Northridge Earthquake of 1994: Ground Motions and Geotechnical Aspects" (PDF). Third International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. Northeastern University College of Engineering. p. 1384. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ↑ Northridge Earthquake Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Retrieved October 6, 2006.

- ↑ USGS Earthquake Information for 1994 "Significant Earthquakes of the World 1994"

- ↑ "ShakeMap Scientific Background".

- ↑ Douglas Dreger. "The Large Aftershocks of the Northridge Earthquake and their Relationship to Mainshock Slip and Fault Zone Complexity". Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ↑ "Significant Earthquakes and Faults, Northridge Earthquake". Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Show Event - NGDC Natural Hazard Images - ngdc.noaa.gov".

- ↑ "USGS Northridge Earthquake 10th Anniversary". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Southern California Earthquake Data Center at Caltech".

- ↑ FEMA

- 1 2 3 Reich, K. Study raises Northridge quake death toll to 72. Los Angeles Times December 20, 1995

- ↑ History Channel

- ↑ Peek-Asa, C.; et al. (1998). "Fatal and hospitalized injuries resulting from the 1994 Northridge earthquake". International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (3): 459–465. doi:10.1093/ije/27.3.459. PMID 9698136.

- ↑ Kloner, R. A.; et al. (1997). "Population-Based Analysis of the Effect of the Northridge Earthquake on Cardiac Death in Los Angeles County, California". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 30 (5): 1174–1180. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00281-7.

- ↑ Leor, J.; et al. (1996). "Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (4): 413–419. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602153340701.

- 1 2 Executive Summary

- ↑ "Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology-- - Federal Highway Administration".

- ↑ "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ Secure Your Stuff: Water Heater

- ↑ Scawthorn; Eidinger; Schiff, eds. (2005). Fire Following Earthquake. Reston, vA: ASCE, NFPA. ISBN 9780784407394.

- ↑ "Coccidioidmycosis Outbreak". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ↑ Cheevers, Jack; Abrahamson, Alan (January 19, 1994), "Earthquake: The Long Road Back : Hospitals Strained to the Limit by Injured : Medical care: Doctors treat quake victims in parking lots. Details of some disaster-related deaths are released", Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Erdmann, Terry J.; Paula M. Block (2010-03-29). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Companion. ISBN 0-671-50106-2.

- ↑ "New Nightmare (1994)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ Susan King, "The 'perfect' '60s woman", Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2012; retrieved April 14, 2012

- ↑ "Flashback: NBC4 Covers 1994 Northridge Earthquake". KNBC. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ↑ "CA Earthquake Authority". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1994 Northridge earthquake. |

- Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- USGS Pasadena

- USC Earthquake Engineering-Strong Motion Group

- SAC Steel Project (Study of welded steel failures)

- Helicopter Footage Filmed After The Quake

- CITY OF LOS ANGELES Re-survey of the San Fernando Valley