Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

| Amundsen–Scott Station | |

|---|---|

| Antarctic base | |

| Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station | |

|

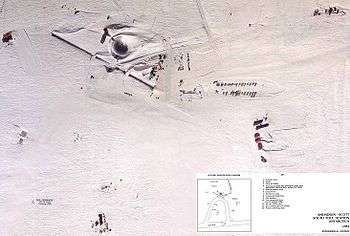

A view of the Amundsen–Scott Station in 2009. In the foreground is Destination Alpha, one of the two main entrances. | |

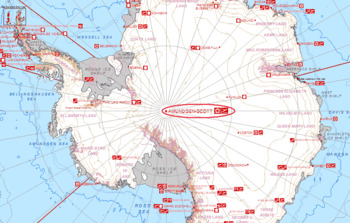

A map of Antarctica showing the location of the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (circled) | |

Amundsen–Scott Station Location of Amundsen–Scott Station at the South Pole in Antarctica | |

| Coordinates: 90°S 00°E / 90°S 0°ECoordinates: 90°S 00°E / 90°S 0°E | |

| Country |

|

| Location in Antarctica | Geographic South Pole, Antarctic Plateau |

| Administered by | United States Antarctic Program by the National Science Foundation |

| Established | November 1956 |

| Named for | Roald Amundsen and Robert F. Scott |

| Elevation[1] | 2,835 m (9,301 ft) |

| Population [1] | |

| • Total |

|

| Time zone | NZST (UTC+12) |

| • Summer (DST) | NZDT (UTC+13) |

| Type | All year-round |

| Period | Annual |

| Status | Operational |

| Facilities |

Facilities include:[1]

|

| Website |

www |

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is a United States scientific research station at the South Pole, the southernmost place on the Earth. The station is located on the high plateau of Antarctica at an elevation of 2,835 metres (9,301 feet) above sea level and is administered by the Division of Polar Programs within the National Science Foundation under the United States Antarctic Program.

The original Amundsen–Scott Station was built by the United States government during November 1956, as a part of its commitment to the scientific goals of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), an international effort lasting from January 1957 through June 1958, to study, among other things, the geophysics of the polar regions.

Before November 1956, there was no permanent human structure at the South Pole, and very little human presence in the interior of Antarctica at all. The few scientific stations in Antarctica were located on and near its seacoast. The station has been continuously occupied since it was built. The Amundsen–Scott Station has been rebuilt, demolished, expanded, and upgraded several times since 1956.

Since the Amundsen–Scott Station is located at the South Pole, it is at the only place on the land surface of the Earth where the sun is continuously up for six months and then continuously down for six months. (The only other such place is at the North Pole, on the sea ice in the middle of the Arctic Ocean.) Thus, during each year, this station experiences one extremely long "day" and one extremely long "night". During the six-month "day", the angle of elevation of the Sun above the horizon varies continuously. The sun rises on the September equinox, reaches its maximum angle above the horizon on the summer solstice in the Southern Hemisphere, around December 20, and sets on the March equinox.

During the six-month "night", it gets extremely cold at the South Pole, with air temperatures sometimes dropping below −73 °C (−99 °F). This is also the time of the year when blizzards, sometimes with gale-force winds, strike the Amundsen–Scott Station. The continuous period of darkness and dry atmosphere make the station an excellent place from which to make astronomical observations, although the moon is up for two weeks of every 27.3 days.

The number of scientific researchers and members of the support staff housed at the Amundsen–Scott Station has always varied seasonally, with a peak population of about 200 in the summer operational season from October to February. In recent years the winter-time population has been around 50 people.

Description and history

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Scientific Station is the southernmost habitation on Earth. It is continuously inhabited. Its name honors Roald Amundsen, whose Norwegian expedition reached the Geographic South Pole in December 1911, and Robert F. Scott, whose British expedition of five men reached the South Pole about one month later (in January 1912) in a race to become the first person ever to reach the South Pole. All of Scott's expedition perished during the journey back towards the coast, while all of Amundsen's expedition returned safely to their base on the seacoast of the continent.

The original Amundsen–Scott Scientific Station was constructed during November 1956 to carry out part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of scientific observations during 1957 through 1958, and the station has been continuously occupied since then. As of 2005, this station lies within 100 meters (330 feet) of the Geographic South Pole. Because this station is located on a moving glacier, this station is, as of 2005, being carried towards the South Pole at a rate of about 10 meters (or yards) per year. Although the United States Government has continuously maintained an installation at the South Pole since 1957, the central berthing, galley, and communications units have been constructed and relocated several times. Each of the installations containing these central units has been named the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station.

Snow accumulation is about 60–80 millimetres (2.4–3.1 in) (water equivalent) per year. The station stands at an elevation of 2,835 meters (9,301 feet) on the interior of Antarctica's nearly featureless ice sheet, which is about 2,700 meters (8,900 feet) thick at that location. The recorded temperature has varied between −12.3 °C (9.9 °F)[2] and −82.8 °C (−117.0 °F), with an annual mean of −49 °C (−56 °F); monthly mean temperatures vary from −28 °C (−18 °F) in December to −60 °C (−76 °F) in July. The average wind speed is 5.5 metres per second (18 ft/s); the peak gust recorded was 25 metres per second (82 ft/s).[3]

Original station (1957–1975)

The original South Pole station, now referred to as "Old Pole", was constructed by an 18-man United States Navy crew during 1956–1957. The crew landed on site in October 1956 and was the first group to winter-over at the South Pole, during 1957. The low temperature recorded during 1957 was −74 °C (−101 °F). These temperatures, combined with low humidity and low air pressure, are survivable only with specialized equipment.

On January 3, 1958, Sir Edmund Hillary's team from New Zealand, part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, reached the station over land from Scott Base, followed shortly by Sir Vivian Fuchs' British scientific component.[4]

The buildings of Old Pole were assembled from prefabricated components delivered to the South Pole by air and airdropped. They were originally built on the surface, with covered wood-framed walkways connecting the buildings. Although snow accumulation in open areas at the South Pole is approximately 8 in (20 cm) per year, wind-blown snow accumulates much more quickly in the vicinity of raised structures. By 1960, three years after the construction of the station, it had already been buried by 6 ft (1.8 m) of snow.[5]

The station was abandoned in 1975 and became deeply buried, with the pressure causing the mostly wooden roof to cave in. The station was demolished in December 2010, after an equipment operator fell through the structure doing snow stability testing for the National Science Foundation (NSF).[6] The area was being vetted for use as a campground for NGO guests.

Dome (1975–2003)

The station was moved and rebuilt in 1975 as a geodesic dome 50 meters (160 feet) wide and 16 meters (52 feet) high, with 14 m × 24 m (46 ft × 79 ft) steel archways, modular buildings, fuel bladders and equipment. Detached buildings within the dome housed instruments for monitoring the upper and lower atmosphere and for numerous and complex projects in astronomy and astrophysics. The station also included the Skylab, a box-shaped tower slightly taller than the dome. Skylab was connected to the Dome by a tunnel. The Skylab housed atmospheric sensor equipment and later a music room.

During the 1970–1974 summers, the dome construction workers were housed in Korean War tents, or "jamesways". These tents consist of a wooden frame with a raised platform covered by canvas. A double-doored exit is at each end. Although the tents are heated, the heat output is not sufficient to keep them at room temperature during the winter. After several jamesways burned down during the 1976–1977 summer, the construction camp was abandoned and later removed.

However, starting in the 1981–1982 summer, extra seasonal personnel have been housed in a group of jamesways known as "summer camp". Initially consisting of only two jamesways, summer camp at its peak consisted of 11 berthing tents housing about 10 people each, two recreational tents and bathroom and gym facilities. In addition, a number of science and berthing structures, such as the hypertats and elevated dorm, were added in the 1990s, particularly for astronomy and astrophysics.

During the period in which the dome served as the main station, many changes to US South Pole operation took place. From the 1990s on, astrophysical research conducted at the South Pole took advantage of its favorable atmospheric conditions and began to produce important scientific results. Such experiments include the Python, Viper, and DASI telescopes, as well as the 10 m (390 in) South Pole Telescope. The DASI telescope has since been decommissioned and its mount used for the Keck Array.[7] The AMANDA / IceCube experiment makes use of the two-mile (3 km)-thick ice sheet to detect neutrinos which have passed through the earth. An observatory building, the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO), was dedicated in 1995. The importance of these projects changed the priorities in station operation, increasing the status of scientific cargo and personnel.

The 1998–99 summer season was the last year that the US Navy operated the five to six LC-130 Hercules service fleet. Beginning in 1999–2000, the New York Air National Guard 109th Airlift Wing took responsibility for the daily cargo and passenger flights between McMurdo Station and the South Pole during the summer.

During the winter of 1988 a loud crack was heard in the dome. Upon investigation it was discovered that the foundation base ring beams were broken due to being overstressed.[8]

The dome was dismantled in late 2009.[9]

Elevated station (2003–present)

In 1992, the design of a new station began for a 7,400 m2 (80,000 sq ft) building with two floor levels that cost $150 million.[10] Construction began in 1999, adjacent to the Dome. The facility was officially dedicated on January 12, 2008 with a ceremony that included the de-commissioning of the old Dome station.[11] The ceremony was attended by a number of dignitaries flown in specifically for the day, including National Science Foundation Director Arden Bement, scientist Susan Solomon and other government officials.

The new station included a modular design, to accommodate an increasing station population, and an adjustable elevation, in order to prevent the station from being buried in snow. In a location where about 20 centimetres (8 in) of snow accumulates every year without ever thawing,[12][13] the building's rounded corners and edges help reduce snow drifts. The building faces into the wind with a sloping lower portion of wall. The angled wall increases the wind speed as it flows under the buildings, and passes above the snow-pack, causing the snow to be scoured away. This prevents the building from being quickly buried. Wind tunnel tests show that scouring will continue to occur until the snow level reaches the second floor.

Because snow gradually settles over time under its own weight, the foundations of the building were designed to accommodate substantial differential settling over any one wing in any one line or any one column. If differential settling continues, the supported structure will need to be jacked up and re-leveled. The facility was designed with the primary support columns outboard of the exterior walls so that the entire building can be jacked up a full floor level. During this process, a new section of column will be added over the existing columns then the jacks pull the building up to the higher elevation.

Astrophysics experiments at the station

- South Pole Telescope (2007–present), used to survey the CMB to look for distant galaxy clusters.[14]

- Viper telescope (1997–2000), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the CMB.[15] Was refitted with the ACBAR bolometer (2000-2008).[16]

- Python Telescope (1992–97),[15] used to observe temperature anisotropies in the CMB.[17]

- AMANDA (1997–2009) was an experiment to detect neutrinos.[18]

- IceCube (2010–present), is an experiment to detect neutrinos.[19]

- The Keck Array (2010–present), using the DASI mount,[7] is now used to continue work on the polarization anisotropies of the CMB.

- The BICEP1 (2006–08) and BICEP2 (2010–2012) instruments were also used to observe polarization anisotropies in the CMB. BICEP3 began collecting data on 15 May 2016.[20]

- The QUaD (2004–09),used the DASI mount, used to make detailed observations of CMB polarizaton.[21][22]

Operation

During the summer the station population is typically around 150. Most personnel leave by the middle of February, leaving a few dozen (45 in 2015) "winter-overs", mostly support staff plus a few scientists, who keep the station functional through the months of Antarctic night. The winter personnel are isolated between mid-February and late October. Wintering-over presents notorious dangers and stresses, as the station population is almost totally isolated. The station is completely self-sufficient during the winter, and powered by three generators running on JP-8 jet fuel. An annual tradition is a back to back viewing of The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1982), and The Thing (2011) after the last flight has left for the winter.[23]

Research at the station includes glaciology, geophysics, meteorology, upper atmosphere physics, astronomy, astrophysics, and biomedical studies. In recent years, most of the winter scientists have worked for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory or for low-frequency astronomy experiments such as the South Pole Telescope and BICEP2. The low temperature and low moisture content of the polar air, combined with the altitude of over 2,743 m (8,999 ft), causes the air to be far more transparent on some frequencies than is typical elsewhere, and the months of darkness permit sensitive equipment to run constantly.

There is a small greenhouse at the station. The variety of vegetables and herbs in the greenhouse, which range from fresh eggplant to jalapeños, are all produced hydroponically, using only water and nutrients and no soil. The greenhouse is the only source of fresh fruit and vegetables during the winter.

Transportation

The station has a runway for aircraft (ICAO: NZSP), 3,658 m (12,001 ft) long. Between October and February, there are several flights per day of ski-equipped LC-130 Hercules aircraft from McMurdo to supply the station. Resupply missions are collectively termed Operation Deep Freeze.

There is a snow road over the ice sheet from McMurdo, the McMurdo-South Pole highway.

Communication

Data access to the station is provided by access via NASA's TDRS-4, 5, and 6, the DOD DSCS-3 satellite & the commercial Iridium satellite constellation. For the 2007–08 season, the TDRS relay (named South Pole TDRSS Relay or SPTR) was upgraded to support a data return rate of 50 Mbit/s, which comprises over 90% of the data return capability.[24][25] The TDRS-1 satellite formerly provided services to the station, but it failed in October 2009 and was subsequently decommissioned. Marisat and LES 9 were also formerly used. In July 2016, the GOES-3 satellite was decommissioned due to it nearing the end of its supply of propellant and was replaced by the use of the DSCS-3 satellite, a military communications satellite. DSCS-3 can provide a 30 MB/s data rate compared to GOES-3's 1.5 MB/s. DSCS-3 and TDRS-4, 5, and 6 are used together to provide the main communications capability for the station. These satellites provide the data uplink for the station's scientific data as well as provide broadband internet and telecommunications access. Only during the main satellite events is the station's telephone system able to dial out. The commercial Iridium satellite is used when the TDRS and DSCS satellites are all out of range to give the station limited communications capability during those times. During those times, telephone calls may only be made on several Iridium satellite telephones owned by the station. The station's IT system also has a limited data uplink over the Iridium network which allows emails less than 100KB to be sent and received and small critical data files to be transmitted. This uplink works by bonding the data stream over 12 voice channels.

Climate

Typical of inland Antarctica, Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station experiences an ice cap climate (EF).[26] The peak season of summer lasts October to February.

| Climate data for the South Pole | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −14.0 (6.8) |

−20.0 (−4) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−27.0 (−16.6) |

−30.0 (−22) |

−28.8 (−19.8) |

−33.0 (−27.4) |

−32.0 (−25.6) |

−29.0 (−20.2) |

−29.0 (−20.2) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −25.9 (−14.6) |

−38.1 (−36.6) |

−50.3 (−58.5) |

−54.2 (−65.6) |

−53.9 (−65) |

−54.4 (−65.9) |

−55.9 (−68.6) |

−55.6 (−68.1) |

−55.1 (−67.2) |

−48.4 (−55.1) |

−36.9 (−34.4) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

−46.27 (−51.28) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −29.4 (−20.9) |

−42.7 (−44.9) |

−57.0 (−70.6) |

−61.2 (−78.2) |

−61.7 (−79.1) |

−61.2 (−78.2) |

−62.8 (−81) |

−62.5 (−80.5) |

−62.4 (−80.3) |

−53.8 (−64.8) |

−40.4 (−40.7) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

−52.03 (−61.66) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −41.0 (−41.8) |

−57.0 (−70.6) |

−71.0 (−95.8) |

−75.0 (−103) |

−78.0 (−108.4) |

−82.8 (−117) |

−80.0 (−112) |

−77.0 (−106.6) |

−79.0 (−110.2) |

−71.0 (−95.8) |

−55.0 (−67) |

−38.0 (−36.4) |

−82.8 (−117) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 558 | 480 | 217 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 434 | 600 | 589 | 2,938 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 18 | 17 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 20 | 19 | 8.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 65 |

| Source #1: Weatherbase [26] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Cool Antarctica [27] | |||||||||||||

Media and events

In 1991, Michael Palin visited the base on the 8th and final episode of his BBC Television Documentary, Pole to Pole.

On January 10, 1995, NASA, PBS, and NSF collaborated for the first live TV broadcast from the South Pole, titled Spaceship South Pole.[28] During this interactive broadcast, students from several schools in the United States asked the scientists at the station questions about their work and conditions at the pole.[29]

In 1999, CBS News correspondent Jerry Bowen reported on camera in a talkback with anchors from the Saturday edition of CBS This Morning.

In 1999, the winter-over physician, Dr. Jerri Nielsen, found that she had breast cancer. She had to rely on self-administered chemotherapy using supplies from a daring July cargo drop, then was picked up in an equally dangerous mid-October landing.

On May 11, 2000, astrophysicist Dr. Rodney Marks became ill while walking between the remote observatory and the base. He became increasingly sick over 36 hours, three times returning increasingly distressed to the station's doctor. Advice was sought by satellite, but Dr Marks died on May 12, 2000 with his condition undiagnosed.[30][31] The National Science Foundation issued a statement that Rodney Marks had "apparently died of natural causes, but the specific cause of death ha[d] yet to be determined".[32] The exact cause of Marks' death could not be determined until his body was removed from Amundsen–Scott Station and flown off Antarctica for an autopsy.[33] Marks' death was due to methanol poisoning, and the case received media attention as the "first South Pole murder",[34] although there is no evidence that Marks died as the result of the act of another person.[35][36]

On 26 April 2001, Kenn Borek Air used a DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft to rescue Dr. Ron Shemenski from Amundsen–Scott.[37][38][39][40] This was the first ever rescue from the South Pole during polar winter.[41] To achieve the range necessary for this flight, the Twin Otter was equipped with a special ferry tank.

In January 2007, the station was visited by a group of high-level Russian officials, including FSB chiefs Nikolay Patrushev and Vladimir Pronichev. The expedition, led by polar explorer Artur Chilingarov, started from Chile on two Mi-8 helicopters and landed at the South Pole.[42][43]

On September 6, 2007, The National Geographic Channel's TV show Man Made aired an episode on the construction of their new facility.[44]

On the November 9, 2007 edition of NBC's Today, Today show co-anchor Ann Curry made a satellite telephone call which was broadcast live from the South Pole.[45]

On Christmas 2007, two employees at the base got into a drunken fight and had to be evacuated.[46]

On July 11, 2011, the winter-over communications technician fell ill and was diagnosed with appendicitis. An emergency open appendectomy was performed by the station doctors with several winter-overs assisting during the surgery.

The 2011 BBC TV programme Frozen Planet discusses the base and shows footage of the inside and outside of the elevated station in the "Last Frontier Episode".

During the 2011 winter-over season, station manager Renee-Nicole Douceur experienced a stroke on August 27, resulting in loss of vision and cognitive function. Because the Amundsen–Scott base lacks diagnostic medical equipment such as an MRI or CT scan machine, station doctors were unable to fully evaluate the damage done by the stroke or the chance of recurrence. Physicians on site recommended a medevac flight as soon as possible for Douceur, but offsite doctors hired by Raytheon Polar Services (the company contracted to run the base) and the National Science Foundation disagreed with the severity of the situation. The National Science Foundation, which is the final authority on all flights and assumes all financial responsibility for the flights, denied the request for medevac saying the weather was still too hazardous.[47] Plans were made to evacuate Douceur on the first flight available. Douceur and her niece, believing Douceur's condition to be grave and believing an earlier medevac flight possible, contacted Senator Jeanne Shaheen for assistance; as the NSF continued to state Douceur's condition did not qualify for a medevac attempt and conditions at the base would not permit an earlier flight, Douceur and her supporters brought the situation to media attention.[48][49]

Douceur was evacuated, along with a doctor and an escort, on an October 17 cargo flight. This was the first flight available when the weather window opened up on October 16. This first flight is usually solely for supply and refueling of the station, and does not customarily accept passengers, as the plane's cabin is unpressurized.[50][51] The evacuation was successful, and Douceur arrived in Christchurch, New Zealand, at 10:55 p.m.[52] She ultimately made a full recovery.[53]

In March 2014, BICEP2 announced that they had detected B-modes from gravitational waves generated in the early universe, supporting the inflation theory of cosmology.[54]

On 20 June 2016, there is another medical evacuation of two personnel around midwinter day, again involving air evac by Kenn Borek Air and Twin Otter aircraft.[55][56][57]

In popular culture

Science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson's book Antarctica features a fictionalized account of the culture at Amundsen–Scott and McMurdo, set in the near future.

The station is featured prominently in the The X-Files movie Fight the Future.

The 2009 film Whiteout is mainly set at the Amundsen–Scott base, although the building layouts are completely different.

Time zone

The South Pole sees the sun rise and set only once a year. Due to atmospheric refraction, these do not occur exactly on the September equinox and the March equinox, respectively: the sun is above the horizon for four days longer at each equinox. The place has no solar time; there is no daily maximum or minimum solar height above the horizon. The station uses New Zealand time (UTC+12, UTC+13 during daylight saving time) since all flights to McMurdo station depart from Christchurch and therefore all official travel from the pole goes through New Zealand.

The zone identifier in the IANA time zone database is Antarctica/South Pole.

See also

- Polheim, Amundsen's name for the first South Pole camp.

- Scott Base

- Research stations in Antarctica

- Vostok Station

- Concordia Station

References

- 1 2 3 "Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station". Giosciences: Polar Programs. National Science Foundation. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ↑ Lazzara, Matthew A. (2011-12-28). "Preliminary Report: Record Temperatures at South Pole (and nearby AWS sites…)". Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ "National Science Foundation South Pole Station". Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Edmund Hillary in Antarctica". Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Barna, Lynette; Courville, Zoe; Rand, John; Delaney, Allan (July 2015). Remediation of Old South Pole Station, Phase I: Ground-Penetrating-Radar Surveys. Hanover, NH: U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "South Pole's first building blown up after 53 years". OurAmazingPlanet.com. March 31, 2011.

- 1 2 "Keck Array Overview". harvard.edu. NSF. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ↑ http://antarcticsun.usap.gov/features/contentHandler.cfm?id=1985

- ↑ https://antarcticsun.usap.gov/features/contenthandler.cfm?id=1984

- ↑ "nsf.gov OPP MREFC South Pole Station Modernization - FY08 budget request" (PDF). Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ "A New Era". The Antarctic Sun. May 1, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ↑ Modern Marvels episode, "Sub-Zero Tech".

- ↑ Initial environmental evaluation – development of blue-ice and compacted-snow runways, National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, April 9, 1993

- ↑ Ruhl, John; et al. (October 2004). "The South Pole Telescope". SPIE. 5498: 11–29. arXiv:astro-ph/0411122

. doi:10.1117/12.552473.

. doi:10.1117/12.552473. - 1 2 "CARA Science: Overview". uchicago.edu. University of Chicago. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Arcminute Cosmology Bolometer Array Receiver: Instrument Description". berkeley.edu. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ Coble, K.; Dragovan, M.; Kovac, J.; Halverson, N. W.; Holzapfel, W. L.; Knox, L.; Dodelson, S.; Ganga, K.; Alvarez, D.; Peterson, J. B.; Griffin, G.; Newcomb, M.; Miller, K.; Platt, S.R.; Novak, G. (July 1, 1999). "Anisotropy in the Cosmic Microwave Background at Degree Angular Scales: Python V Results". The Astrophysical Journal. 519 (1): L5–L8. arXiv:astro-ph/9902195

. doi:10.1086/312093.

. doi:10.1086/312093. - ↑ Mgrdichian, Laura. "Amanda's First Six Years". phys.org. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ "IceCube South Pole Neutrino Observatory". icecube.wisc.edu. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ Francis, Matthew R. (16 May 2016). "Dusting for the fingerprint of inflation with BICEP3". Symmetry magazine.

- ↑ Ade, P.; Bock, J.; Bowden, M.; Brown, M. L.; Cahill, G.; Carlstrom, J. E.; Castro, P. G.; Church, S.; Culverhouse, T.; Friedman, R.; Ganga, K.; Gear, W. K.; Hinderks, J.; Kovac, J.; Lange, A. E.; Leitch, E.; Melhuish, S. J.; Murphy, J. A.; Orlando, A.; Schwarz, R.; O’Sullivan, C.; Piccirillo, L.; Pryke, C.; Rajguru, N.; Rusholme, B.; Taylor, A. N.; Thompson, K. L.; Wu, E. Y. S.; Zemcov, M. (February 10, 2008). "First Season QUaD CMB Temperature and Polarization Power Spectra". The Astrophysical Journal. 674 (1): 22–28. arXiv:0705.2359

. doi:10.1086/524922.

. doi:10.1086/524922. - ↑ Brown, M. L.; Ade, P.; Bock, J.; Bowden, M.; Cahill, G.; Castro, P. G.; Church, S.; Culverhouse, T.; Friedman, R. B.; Ganga, K.; Gear, W. K.; Gupta, S.; Hinderks, J.; Kovac, J.; Lange, A. E.; Leitch, E.; Melhuish, S. J.; Memari, Y.; Murphy, J. A.; Orlando, A.; Sullivan, C. O'; Piccirillo, L.; Pryke, C.; Rajguru, N.; Rusholme, B.; Schwarz, R.; Taylor, A. N.; Thompson, K. L.; Turner, A. H.; Wu, E. Y. S.; Zemcov, M. (November 1, 2009). "IMPROVED MEASUREMENTS OF THE TEMPERATURE AND POLARIZATION OF THE COSMIC MICROWAVE BACKGROUND FROM QUaD". The Astrophysical Journal. 705 (1): 978–999. arXiv:0906.1003

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/1/978.

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/1/978. - ↑ "The Antarctic Sun". antarcticsun.com. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "South Pole-News". Southpolestation.com. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ "South Pole TDRSS Relay (SPTR)". Msp.gsfc.nasa.gov. September 1, 2000. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- 1 2 "South Pole, Antarctica". WeatherBase. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Antarctica Climate data and graphs". Archived from the original on October 9, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Live From Antarctica". Passport to Knowledge. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ↑ Greg Falxa. "Tech Crew at the South Pole Interactive TV Broadcast". Falxa.net. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "In Memoriam". The CfA Almanac Vol. XIII No. 2, July 2000. Retrieved on December 19, 2006.

- ↑ Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. Memorial. Retrieved on December 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Antarctic Researcher Dies". National Science Foundation Office of Legislative and Public Affairs, Press release May 12, 2000. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Australian scientist dies during Pole winter". The Antarctic Sun October 22, 2000. Retrieved on December 19, 2006.

- ↑ Chapman, Paul (December 14, 2006). "New Zealand Probes What May Be First South Pole Murder". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Death of Australian astrophysicist an Antarctic whodunnit". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. December 14, 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ↑ Cockrell, Will (December 2009). "A Mysterious Death at the South Pole". Men's Journal. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Canadian Press (23 January 2013). "Bad weather hampers search for 3 Canadians on plane missing in Antarctica". Global News. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ CTV News (23 January 2013). "Kenn Borek plane carrying three Canadians missing in Antarctica". CTV. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ Bob Antol (April 2001). "The Rescue of Dr. Ron Shemenski from the South Pole". Bob Antol's Polar Journals. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- ↑ "Doctor rescued from Antarctica safely in Chile". New Zealand Herald. 27 April 2001. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- ↑ TRANSCRIPT (26 April 2001). "Plane With Dr. Shemenski Arrives in Chile". CNN. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ Patrushev lands at South Pole during Antarctic expedition Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Two Russian helicopters land at the South Pole". Timesrussia.com. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ National Geographic Channel's South Pole Project Archived October 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ann Curry's live broadcast from the South Pole". MSNBC. November 9, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ McMahon, Barbara (December 27, 2007). "Antarctic base staff evacuated after Christmas brawl". London: Guardian. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Pilot describes Antarctica wx challenges". www.weather.com.

- ↑ "Worker at South Pole Station Pushes for a Rescue After a Stroke". New York Times. October 7, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Evacuation is denied for South Pole stroke victim". MSNBC. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Raytheon worker stuck in South Pole is coming home". Boston Herald. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ "South Pole: Stroke Victim Waits for Plane Flight". ABC News. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Sick American engineer flies out of South Pole - US news - Life - msnbc.com". MSNBC. 2011-10-17. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ South Pole stroke victim recovering at Johns Hopkins

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Detection of Waves in Space Buttresses Landmark Theory of Big Bang". New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Antarctic medical evacuation planes reach British station at Rothera" (Press release). Virginia, USA: National Science Foundation. June 20, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ "News". South Pole News. July 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin (June 22, 2016). "Rescue Flight Lands at South Pole to Evacuate Sick Worker". New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. |

- Live webcam image from Usap

- Amundsen–Scott Station Noaa webcam

- National Science Foundation: Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

- Unofficial website on the Station: news, gallery, history

- personal record South Pole winter-over page

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities Map

- weak nuclear force, another personal record South pole winter-over page.

- Airport information for NZSP at World Aero Data. Data current as of October 2006.

- Current weather for NZSP at NOAA/NWS

.svg.png)