Ananda Coomaraswamy

| Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy | |

|---|---|

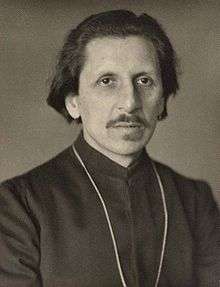

Coomaraswamy in 1916, photograph by Alvin Langdon Coburn | |

| Born |

22 August 1877 Colombo, British Ceylon |

| Died |

9 September 1947 (aged 70) Needham, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | Sri Lankan American |

| Known for | Metaphysician, philosopher, historian |

| Religion | Hindu |

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy (Tamil: ஆனந்த குமாரசுவாமி, Ānanda Kentiś Kumāraswāmī; 22 August 1877 − 9 September 1947) was a Ceylonese Tamil philosopher and metaphysician, as well as a pioneering historian and philosopher of Indian art, particularly art history and symbolism, and an early interpreter of Indian culture to the West.[1] In particular, he is described as "the groundbreaking theorist who was largely responsible for introducing ancient Indian art to the West."[2]

Life

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy was born in Colombo, Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, to the Ceylonese Tamil legislator and philosopher Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy of the aristocratic Vellalar Ponnambalam-Coomaraswamy family and his English wife Elizabeth Beeby.[3][4][5] His father died when Ananda was two years old, and Ananda spent much of his childhood and education abroad.

Coomaraswamy moved to England in 1879 and attended Wycliffe College, a preparatory school in Stroud, Gloucestershire, at the age of twelve. In 1900, he graduated from University College, London, with a degree in geology and botany. On 19 June 1902, Coomaraswamy married Ethel Mary Partridge, an English photographer, who then traveled with him to Ceylon. Their marriage lasted until 1913. Coomaraswamy's field work between 1902 and 1906 earned him a doctor of science for his study of Ceylonese mineralogy, and prompted the formation of the Geological Survey of Ceylon which he initially directed.[6] While in Ceylon, the couple collaborated on Mediaeval Sinhalese Art; Coomaraswamy wrote the text and Ethel provided the photographs. His work in Ceylon fueled Coomaraswamy's anti-Westernization sentiments.[7] After their divorce, Partridge returned to England, where she became a famous weaver and later married the writer Philip Mairet.

By 1906, Coomaraswamy had made it his mission to educate the West about Indian art, and was back in London with a large collection of photographs, actively seeking out artists to try to influence. He knew he could not rely on Museum curators or other members of the cultural establishment – in 1908 he wrote "The main difficulty so far seems to have been that Indian art has been studied so far only by archaeologists. It is not archaeologists, but artists … who are the best qualified to judge of the significance of works of art considered as art." By 1909, he was firmly acquainted with Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill, the city's two most important early Modernists, and soon both of them had begun to incorporate Indian aesthetics into their work. The curiously hybrid sculptures that were produced as a result can be seen to form the very roots of what is now considered British Modernism.[8][9]

.

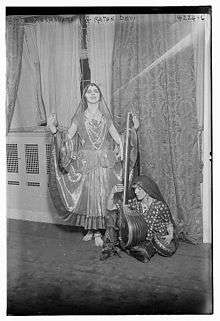

Coomaraswamy then met and married a British woman Alice Ethel Richardson and together they went to India and stayed on a houseboat in Srinagar in Kashmir. Commaraswamy studied Rajput painting whilst his wife studied Indian music with Abdul Rahim of Kapurthala. When they returned to England Alice performed Indian song under the stage name Ratan Devi. They had two children, a son, Narada, and daughter, Rohini. Alice was successful and they both went to America when Ratan Devi did a concert tour.[10] Whilst they were there Coomaraswamy was invited to serve as the first Keeper of Indian art in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1917.[11]

Coomaraswamy divorced his second wife after they arrived in America.[11] He married the American artist Stella Bloch, 29 years his junior, in November 1922. Through the 1920s, Coomaraswamy and his wife were part of the bohemian art circles in New York City, Coomaraswamy befriending Alfred Stieglitz and the artists who exhibited at Stieglitz's gallery. At the same time, he was studying Sanskrit and Pali religious literature as well as Western religious works. He wrote catalogues for the Museum of Fine Arts and published his History of Indian and Indonesian Art in 1927.

After the couple divorced in 1930, they remained friends. Shortly thereafter, on 18 November 1930, Coomaraswamy married Argentine Luisa Runstein, 28 years younger, who was working as a society photographer under the professional name Xlata Llamas. They had a son, Coomaraswamy's third child, Rama Ponnambalam (1929-2006), who became a physician and convert at age 22 to the Roman Catholic Church. Following Vatican II, he became a critic of the reforms and author of Catholic Traditionalist works.[12] He was also ordained a Traditionalist Roman Catholic priest, despite the fact that he was married and had a living wife.[13]

In 1933 Coomaraswamy's title at the Museum of Fine Arts changed from curator to Fellow for Research in Indian, Persian, and Mohammedan Art.[7]

He served as curator in the Museum of Fine Arts until his death in Needham, Massachusetts, in 1947. During his long career, he was instrumental in bringing Eastern art to the West. In fact, while at the Museum of Fine Arts, he built the first substantial collection of Indian art in the United States.[14]

He also helped with the collections of Persian Art at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Fine Arts.

After Coomaraswamy's death, his widow, Doña Luisa Runstein, acted as a guide and resource for students of his work.

Contributions

Coomaraswamy made important contributions to the philosophy of art, literature, and religion. In Ceylon, he applied the lessons of William Morris to Ceylonese culture and, with his wife Ethel, produced a groundbreaking study of Ceylonese crafts and culture. While in India, he was part of the literary circle around Rabindranath Tagore, and he contributed to the "Swadeshi" movement, an early phase of the struggle for Indian independence. In the 1920s, he made pioneering discoveries in the history of Indian art, particularly some distinctions between Rajput and Moghul painting, and published his book Rajput Painting. At the same time he amassed an unmatched collection of Rajput and Moghul paintings, which he took with him to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, when he joined its curatorial staff in 1917. Through 1932, from his base in Boston, he produced two kinds of publications: brilliant scholarship in his curatorial field but also graceful introductions to Indian and Asian art and culture, typified by The Dance of Shiva, a collection of essays that remain in print to this day. Deeply influenced by René Guénon, he became one of the founders of the Traditionalist School. His books and essays on art and culture, symbolism and metaphysics, scripture, folklore and myth, and still other topics, offer a remarkable education to readers who accept the challenges of his resolutely cross-cultural perspective and his insistence on tying every point he makes back to sources in multiple traditions. He once remarked, "I actually think in both Eastern and Christian terms—Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Pali, and to some extent Persian and Chinese."[15] Alongside the deep and not infrequently difficult writings of this period, he also delighted in polemical writings created for a larger audience—essays such as "Why exhibit works of art?" (1943).[16]

In his book The Information Society: An Introduction (Sage, 2003, p. 44), Armand Mattelart credits Coomaraswamy for coining the term 'post-industrial' in 1913.

Perennial philosophy

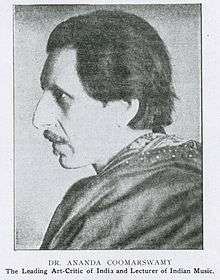

He was described by Heinrich Zimmer as "That noble scholar upon whose shoulders we are still standing."[17] While serving as a curator to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the latter part of his life, he devoted his work to the explication of traditional metaphysics and symbolism. His writings of this period are filled with references to Plato, Plotinus, Clement, Philo, Augustine, Aquinas, Shankara, Eckhart and other mystics. When asked what he was foremostly, he said that he was a "metaphysician", referring to the concept of perennial philosophy, or sophia perennis.

Along with René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon, Coomaraswamy is regarded as one of the three founders of Perennialism, also called the Traditionalist School. Several articles by Coomaraswamy on the subject of Hinduism and the perennial philosophy were published posthumously in the quarterly journal Studies in Comparative Religion alongside articles by Schuon and Guénon among others.

Although he agrees with Guénon on the universal principles, Coomaraswamy's works are very different in form. By vocation, he was a scholar who dedicated the last decades of his life to "searching the Scriptures". He offers a perspective on the tradition which complements Guénon's. He was extremely perceptive regarding aesthetics and wrote dozens of articles on traditional arts and mythology. His works are also finely balanced intellectually. Although born in the Hindu tradition, he had a deep knowledge of the Western tradition as well as a great expertise in, and love for, Greek metaphysics, especially that of Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism.

He built a bridge between East and West that was designed to be two-way: among other things, his metaphysical writings aimed at demonstrating the unity of the Vedanta and Platonism. His works also sought to rehabilitate original Buddhism, a tradition that Guénon had for a long time limited to a rebellion of the Kshatriyas against Brahmin authority.

"Alan Antliff documents (...in I Am Not A Man, I Am Dynamite) how the Indian art critic and anti-imperialist Ananda Coomaraswamy combined Nietzsche's individualism and sense of spiritual renewal with both Kropotkin's economics and with Asian idealist religious thought. This combination was offered as a basis for the opposition to British colonization as well as to industrialization."[18]

Works by Coomaraswamy

- Traditional art

- Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought?: The Traditional View of Art, (World Wisdom 2007)

- Introduction To Indian Art, (Kessinger Publishing, 2007)

- Buddhist Art, (Kessinger Publishing, 2005)

- Guardians of the Sundoor: Late Iconographic Essays, (Fons Vitae, 2004)

- History of Indian and Indonesian Art, (Kessinger Publishing, 2003)

- Teaching of Drawing in Ceylon] (1906, Colombo Apothecaries)

- "The Indian craftsman" (1909, Probsthain: London)

- Viśvakarmā ; examples of Indian architecture, sculpture, painting, handicraft (1914, London)

- Vidyāpati: Bangīya padābali; songs of the love of Rādhā and Krishna], (1915, The Old Bourne press: London)

- The mirror of gesture: being the Abhinaya darpaṇa of Nandikeśvara (with Duggirāla Gōpālakr̥ṣṇa) (1917, Harvard University Press; 1997, South Asia Books,)

- Indian music (1917, G. Schirmer; 2006, Kessinger Publishing,

- A catalog of sculptures by John Mowbray-Clarke: shown at the Kevorkian Galleries, New York, from May the seventh to June the seventh, 1919. (1919, New York: Kevorkian Galleries, co-authored with Mowbray-Clarke, John, H. Kevorkian, and Amy Murray)

- Rajput Painting, (B.R. Publishing Corp., 2003)

- Early Indian Architecture: Cities and City-Gates, (South Asia Books, 2002) I

- The Origin of the Buddha Image, (Munshirm Manoharlal Pub Pvt Ltd, 2001)

- The Door in the Sky, (Princeton University Press, 1997)

- The Transformation of Nature in Art, (Sterling Pub Private Ltd, 1996)

- Bronzes from Ceylon, chiefly in the Colombo Museum, (Dept. of Govt. Print, 1978)

- Early Indian Architecture: Palaces, (Munshiram Manoharlal, 1975)

- The arts & crafts of India & Ceylon, (Farrar, Straus, 1964)

- Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, (Dover Publications, 1956)

- Archaic Indian Terracottas, (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1928)

- Metaphysics

- Hinduism And Buddhism, (Kessinger Publishing, 2007; Golden Elixir Press, 2011)

- Myths of the Hindus & Buddhists (with Sister Nivedita) (1914, H. Holt; 2003, Kessinger Publishing)

- Buddha and the gospel of Buddhism (1916, G. P. Putnam's sons; 2006, Obscure Press,)

- A New Approach to the Vedas: An Essay in Translation and Exegesis, (South Asia Books, 1994)

- The Living Thoughts of Gotama the Buddha, (Fons Vitae, 2001)

- Time and eternity, (Artibus Asiae, 1947)

- Perception of the Vedas, (Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 2000)

- Metaphysics, (Princeton University Press, 1987)

- Social criticism

- Am I My Brothers Keeper, (Ayer Co, 1947)

- "The Dance of Shiva - Fourteen Indian essays" Turn Inc., New York; 2003, Kessinger Publishing,

- The village community and modern progress (12 pages) (Colombo Apothecaries, 1908)

- Essays in national idealism (Colombo Apothecaries, 1910)

- Bugbear of Literacy, (Sophia Perennis, 1979)

- What is Civilisation?: and Other Essays. Golgonooza Press, (UK),

- Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government, (Oxford University Press, 1994)

- Posthumous collections

- Yaksas, (Munshirm Manoharlal Pub Pvt Ltd, 1998) ISBN 978-81-215-0230-6

- Coomaraswamy: Selected Papers, Traditional Art and Symbolism, (Princeton University Press, 1986)

- The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy , (2003, World Wisdom)

Works about Coomaraswamy

- Ananda Coomaraswamy: remembering and remembering again and again, by S. Durai Raja Singam. Publisher: Raja Singam, 1974.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, by P. S. Sastri. Arnold-Heinemann Publishers, India, 1974.

- Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy: a handbook, by S. Durai Raja Singam. Publisher s.n., 1979.

- Ananda Coomaraswamy: a study, by Moni Bagchee. Publisher: Bharata Manisha, 1977.

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, by Vishwanath S. Naravane. Twayne Publishers, 1977. ISBN 0-8057-7722-9.

- Selected letters of Ananda Coomaraswamy, Edited by Alvin Moore, Jr; and Rama P. Coomaraswamy (1988)

- Coomaraswamy: Volume I: Selected Papers, Traditional Art and Symbolism, Princeton University Press (1977)

- Coomaraswamy: Volume II: Selected Papers, Metaphysics, Edited by Roger Lipsey, Princeton University Press (1977)

- Coomaraswamy: Volume III: His Life and Work, by Roger Lipsey, Princeton University Press (1977)

See also

- Ivan Aguéli

- Titus Burckhardt

- Calico Museum of Textiles

- Comparative Religion

- Esoterism

- René Guénon

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr

- Martin Lings

- Whitall Perry

- Huston Smith

- William Stoddart

- Michel Valsan

- Advaita Vedanta

References

- ↑ Murray Fowler, "In Memoriam: Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy", Artibus Asiae, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1947), pp. 241-244

- ↑ MFA: South Asian Art. Archived from the original Archived 15 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Annual Ananda Coomaraswamy Memorial Oration 1999". Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Kathleen Taylor, Sir John Woodroffe Tantra and Bengal, Routledge (2012), p. 63

- ↑ Journal of Comparative Literature & Aesthetics, Volume 16 (1993), p. 61

- ↑ Philip Rawson, "A Professional Sage", The New York Review of Books, v. 26, no. 2 (February 22, 1979)

- 1 2 "Stella Bloch Papers Relating to Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, 1890-1985 (bulk 1917-1930)". Princeton University Library Manuscripts Division.

- ↑ Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard. Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African and Pacific Art and the London Avant Garde. Oxford University Press, 2011, passim. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9.

- ↑ Video of a Lecture discussing Coomaraswamy's role in the introduction of Indian art to Western Modernists, School of Advanced Study, March 2012.

- ↑ Alice Richardson, Making Britain, Open University, Retrieved 17 October 2015

- 1 2 G. R. Seaman, Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish (1877–1947), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 17 Oct 2015

- ↑ "Rama P.Coomaraswamy (1929-2006)" by William Stoddart and Mateus Soares de Azevedo (3 pdfs)

- ↑ "On the Validity of My Ordination" by Dr. Rama P. Coomaraswamy

- ↑ Princeton University Press, The Door in the Sky: Coomaraswamy on Myth and Meaning

- ↑ Anand Coomaraswamy A Pen Sketch By - Dr. Rama P. Coomaraswamy

- ↑ Why Exhibit Works of Art? Archived 28 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine., essay. He also published a book of that title.

- ↑ Multiworld.org/m_versity/althinkers... - StumbleUpon

- ↑ Spencer Sunshine, "Nietzsche and the Anarchists"

Sources

- T.Wignesan, "Ananda K. Coomaraswamy’s Aesthetics" # Tamil studies Now published in the collection: T.Wignesan. Rama and Ravana at the Altar of Hanuman: On Tamils, Tamil Literature & Tamil Culture. Allahabad:Cyberwit.net, 2008, 750p. & at Chennai: Institute of Asian Studies, 2007, 439p.

- "Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy" in One Hundred Tamils of the 20th Century

- "Coomaraswamy, Ananda K.", Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, vol. 1, ed. Amaresh Dutta, Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 768. ISBN 81-260-1803-8

- Mattelart, Armand. The Information Society: An Introduction, Sage: London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, 2003, p. 44.

External links

- Works by Ananda Coomaraswamy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ananda Coomaraswamy at Internet Archive

- Books by Coomaraswamy - Fons Vitae Series

- 1999 Coomaraswamy lecture by Sandrasagra

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy at WorldCat

- Coomaraswamy bibliography at religioperennis.org

- "Ananda K. Coomaraswamy’s Life and Work" at World Wisdom publishers

- The Colonial Context and Aesthetic Identity Formation: Coomaraswamy, A Case Study by Binda Paranjpe

- Coomaraswamy’s Impetus to Eastern Spirit

- Coomarswamy in Dictionary of Art Historians

- Ananda Coomaraswamy materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)