André Antoine

| André Antoine | |

|---|---|

|

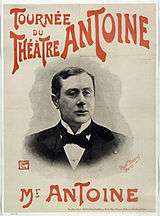

Antoine c. 1900, published in 1908 by Chocolats Félix Potin | |

| Born |

31 January 1858 Limoges, France |

| Died |

23 October 1943 (aged 85) Loire-Atlantique, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Cercle Gaulois |

| Known for | Theatre Director |

| Movement | Naturalism |

| Spouse(s) | Pauline Verdavoine |

| Awards | Officier, Lègion d'Honneur |

André Antoine (31 January 1858 – 23 October 1943) was a French actor, theatre manager, film director, author, and critic who is considered the father of modern mise en scène in France.

Biography

André Antoine was a clerk at the Paris Gas Utility and worked in the Archer Theatre when he asked to produce a dramatization of a novel by Émile Zola. The amateur group refused it, so he decided to create his own theatre to realize his vision of the proper development of dramatic art.

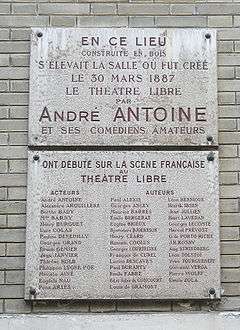

Antoine founded the Théâtre Libre in Paris in 1887. This was a théâtre d'essai, a workshop theatre, where plays were produced whether they would perform at the box office or not. It was also a stage for new writing whose subject matter or form had been rejected in other theatres. Over a seven-year period, until 1894, the Théâtre Libre staged some 111 plays. His work had enormous influence on the French stage, as well as on similar companies elsewhere in Europe, such as the Independent Theatre Society in London and the Freie Buhne in Germany.[1]

Antoine opposed the traditional teachings of the Paris Conservatory, and focused on a more naturalistic style of acting and staging. In particular, Théâtre Libre productions were inspired by the Meiningen Ensemble of Germany. They performed works by Zola, Becque, Brieux, and plays by contemporary German, Scandinavian, and Russian naturalists. In 1894, Antoine was forced to relinquish the theater due to financial failure, but he went on to form Théâtre Antoine, which followed the traditions established by Théâtre Libre until its demise 10 years later.

The work of the Theatre Libre was said to embrace both Realism and Naturalism. In theatre, Realism is generally thought to be a 19th-century movement which uses dramatic and stylistic conventions to bring authenticity and 'real life' to performances and drama texts while Naturalism is commonly seen as an extension to this where an attempt is made to create a perfect illusion of reality. Naturalism is often said to be driven by Darwinism and its view of humans as behavioral creatures shaped by heredity and environment. Antoine believed that our environment determines our character and he would often start rehearsals by creating the set, settings or environment which would then allow his actors to explore their characters and their behaviors with greater authenticity.[2] Often he would only hire untrained actors (a practice still common with young film makers) since he believed that the professional actors of his time could not realistically portray real people.

Antoine's Theatre Libre dedicated itself more specifically to the Quart d'heure or short, simple, free, episodic, one act play performances. he concentrated on script development but advocated naturalistic, behavioral acting dependent on the interaction of actors and helping acting to find their psychological motivations. Discussions on matters of interpretation and setting were a normal part of rehearsals with actors.[3] Antoine believed each play had its unique mood or atmosphere and he hardly ever reused sets and settings. He also literally believed in the notion of removing the fourth wall. With some plays he would rehearse in the space with four walls around the action, natural set and actors and then decide which fourth wall to remove and thus deciding which side or perspective to place the audience on. Plays performed at the Théâtre Libre were often "thin on plot, dense in social and psychological implication" (Chothia, Andre Antoine). Productions rejected formal acting styles that were prevalent at the time and they built the "fourth wall." Despite being proponents of naturalism, they still adhered to some ideas of "playing for the audience" – there is no evidence that Antoine ever set any chairs facing away from the audience, and the actors still had to make sure that their voices could be heard to the back of the house—so, in a way, their "naturalism" was really just a higher level of illusion than theatre had been up to that point.

In 1894, Antoine gave up the direction of his own theatre, and became connected with the Gymnase, and two years later, with the Odéon theatres. Heavily indebted, he left the Odéon in 1914 and turned to the cinema. Meanwhile, he stayed a short period in Istanbul in order to found The Istanbul City Theater. Once World War I started he returned to Paris. Between 1915 and 1922, he directed several films under auspices of the Société cinématographique des auteurs et gens de lettres ("Film Society of Authors and Men of Letters") of Pierre Decourcelle, adapting literary or dramatic works, such as La Terre ("Earth"), Les Frères corses ("The Corsican Brothers") and Quatre-vingt-treize ("Ninety-three"). He applied the principles of naturalism to film, giving importance to the scenery, natural elements that actually determine the behavior of the protagonists, and by using non-professional actors who were not tied up in the old forms of theater. For Jean Tulard, his literary reputation and is involved in "giving the film its sense of nobility". Influencing film makers like Mercanton, Capellans Hervil and he is "the true father of neorealism".

Antoine concluded his career as a theatre and film critic beginning in 1919. For twenty years, his commentary was published by L'Information, and more sporadically in Le Journal, Comœdia, and Le Monde illustré. Two volumes of memoirs were published in 1928, and appeared in the journal Théâtre from 1932 to 1933.

Work

Writings

- Mes souvenirs sur le Théâtre-Libre, 1928

- Mes souvenirs sur le Théâtre Antoine, 1928

Theatrical Productions

Films

(Works as film director)

- The Corsican Brothers (1917)

- Le Coupable (1917)

- Les Travailleurs de la mer (1917)

- L'Hirondelle et la mésange (1920) (forgotten for 60 years, première in 1982)

- Quatre-vingt-treize (1920)

- Mademoiselle de la Seiglière (1920)

- La Terre (1921)

- L'Arlésienne (1922)

References

Sources

- "André Antoine." International Dictionary of Theatre. Vol. 3. Gale, 1996. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 24 Sep. 2011.

- André Antoine, at Cinéclub de Caen. Web.

- André-Paul Antoine, Antoine, père et fils. Paris: Julliard, 1962. Print.

- Antoine, André, Microsoft Encarta 2000, Microsoft Corporation, 1999. Web.

- Bourbonnaud, David "André Antoine, diffuseur et traducteur?" Revue Protée: Les formes culturelles de la communication, volume 30, number 1, Spring 2002. Web.

- Dort, Bernard. "Antoine, le patron", Théâtre Public. Paris: Seuil, 1967. Web.

- Eckersley, M. "It's All a Matter of Style - Naturalistic Theatre Forms." Mask. Drama Victoria: Melbourne, 8. Web.

- Mitter, Shomit and Maria Shevtsova. Fifty Key Theatre Directors. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

- Sarrazac, Jean-Pierre and Philippe Marcerou, Antoine, l'invention de la mise en scène, Actes Sud-Papiers (coll. Parcours de théâtre), 1999. Web. (ISBN 978-2742725120)

- Théatre Antoine at Theatreonline.com. Web.

External links

- Official site of the Théâtre Antoine (French)

- "Collection Théâtrale André Antoine". University of St. Michael's College, John M. Kelly Library. Retrieved 15 October 2015.