Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and Loire rivers, that includes the Brittany peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic coast.[1] The toponym is based on the Gaulish phrase are-mori "on/at [the] sea", made into the Gaulish place name Aremorica (*are-mor-ika ) "Place by the Sea". The suffix -ika was first used to create adjectival forms and then, names (see regions such as Pays d'Ouche from Utica and Perche from Pertica). The original designation was vague, including a large part of what became Normandy in the 10th century and, in some interpretations, the whole of the coast down to the Garonne river. Later, the term became restricted to Brittany.

In Breton (which belongs to the Brythonic branch of the Insular Celtic languages, along with Welsh and Cornish), "on [the] sea" is war vor (Welsh ar fôr – "f" being voiced, as "v" is in English), though the older form arvor is used to refer to the coastal regions of Brittany, in contrast to argoad (ar "on/at", coad "forest" [Welsh ar goed (coed "trees")]) for the inland regions.[2] These cognate modern usages suggest that the Romans first contacted coastal people in the inland region and assumed that the regional name Aremorica referred to the whole area, both coastal and inland.

History of Armorica

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (4.17.105), claims that Armorica was the older name for Aquitania, stating Armorica's southern boundary extended to the Pyrenees. Taking into account the Gaulish origin of the name, this is perfectly correct and logical, as Aremorica is not a 'country name', but a word that describes a type of geographical region - a region that is by the sea. Pliny lists the following Celtic tribes as living in the area: the Aedui and Carnuteni as having treaties with Rome; the Meldi and Secusiani as having some measure of independence; and the Boii, Senones, Aulerci (both the Eburovices and Cenomani), the Parisii, Tricasses, Andicavi, Viducasses, Bodiocasses, Veneti, Coriosvelites, Diablinti, Rhedones, Turones, and the Atseui.

Trade between Armorica and Britain, described by Diodorus Siculus and implied by Pliny[3] was long-established. Because, even after the campaign of Publius Crassus in 57 BC, continued resistance to Roman rule in Armorica was still being supported by Celtic aristocrats in Britain, Julius Caesar led two invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 in response. Some hint of the complicated cultural web that bound Armorica and the Britanniae (the "Britains" of Pliny) is given by Caesar when he describes Diviciacus of the Suessiones, as "the most powerful ruler in the whole of Gaul, who had control not only over a large area of this region but also of Britain"[4] Archaeological sites along the south coast of England, notably at Hengistbury Head, show connections with Armorica as far east as the Solent. This 'prehistoric' connection of Cornwall and Brittany set the stage for the link that continued into the medieval era. Still farther East, however, the typical Continental connections of the Britannic coast were with the lower Seine valley instead.

Archeology has not yet been as enlightening in Iron-Age Armorica as the coinage, which has been surveyed by Philip de Jersey.[5]

Under the Roman Empire, Armorica was administered as part of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis, which had its capital in Lugdunum, (modern day Lyon). When the Roman provinces were reorganized in the 4th century, Armorica (Tractus Armoricanus et Nervicanus) was placed under the second and third divisions of Lugdunensis. After the legions retreated from Britannia (407) the local elite there expelled the civilian magistrates in the following year; Armorica too rebelled in the 430s and again in the 440s, throwing out the ruling officials, as the Romano-Britons had done. At the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 a Roman coalition led by General Flavius Aetius and the Visigothic King Theodoric I clashed violently with the Hunnic alliance commanded by King Attila the Hun. Jordanes lists Aëtius' allies as including Armoricans and other Celtic or German tribes (Getica 36.191).

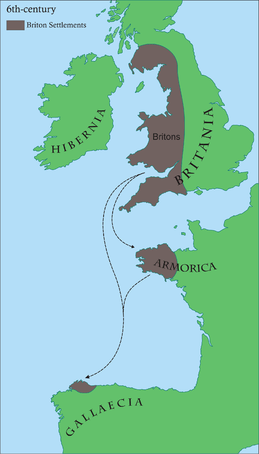

The "Armorican" peninsula came to be settled with Britons from Britain during the poorly documented period of the 5th-7th centuries.[6] Even in distant Byzantium Procopius heard tales of migrations to the Frankish mainland from the island, largely legendary for him, of Brittia.[7] These settlers, whether refugees or not, made the presence felt of their coherent groups in the naming of the westernmost, Atlantic-facing provinces of Armorica, Cornouaille ("Cornwall") and Domnonea ("Devon").[8] These settlements are associated with leaders like Saints Samson of Dol and Pol Aurelian, among the "founder saints" of Brittany.

The linguistic origins of Breton are clear: it is a Brythonic language descended from the Celtic British language, like Welsh and Cornish one of the Insular Celtic languages, brought by these migrating Britons. Still, questions of the relations between the Celtic cultures of Britain— Cornish and Welsh— and Celtic Breton are far from settled. Martin Henig (2003) suggests that in Armorica as in sub-Roman Britain,

"there was a fair amount of creation of identity in the migration period. We know that the mixed, but largely British and Frankish population of Kent repackaged themselves as 'Jutes', and the largely British populations in the lands east of Dumnonia (Devon and Cornwall) seem to have ended up as 'West Saxons'. In western Armorica the small elite which managed to impose an identity on the population happened to be British rather than 'Gallo-Roman' in origin, so they became Bretons. The process may have been essentially the same."[9]

According to C.E.V. Nixon, the collapse of Roman power and the depredations of the Visigoths led Armorica to act "like a magnet to peasants, coloni, slaves and the hard-pressed" who deserted other Roman territories, further weakening them.[10]

When Vikings or Northmen settled in the Cotentin peninsula and the lower Seine around Rouen in the ninth and early tenth centuries, and these regions came to be known as Normandy, the name Armorica fell out of use in the area. With western Armorica having already evolved into Brittany, the east was recast from a Frankish viewpoint as the Breton March under a Frankish marquis.

Armorica popularized in contemporary culture

The home village of the fictional comic-book hero Asterix was located in Armorica during the Roman Republic; there, "indomitable Gauls" hold out against Rome. This unnamed village was reported as having been discovered by archaeologists in a spoof article in the British The Independent newspaper on April Fool's Day, 1993.[11]

North Armorica is mentioned in the first sentence of James Joyce's novel Finnegans Wake.

Armorica is featured extensively in Bernard Cornwell's novel The Winter King where Ynys Trebes, later Mont Saint Michel is besieged and destroyed by the Franks.

In The Farfarers, Before the Norse,[12] Farley Mowat speculated that Armorica was the origin of the Albans, who fled from Romans to Britain and Orkney, and later fled from Norse, discovering Iceland, Greenland, Ungava Peninsula Quebec and Newfoundland.

The protagonist, Mathurin Kerbouchard, of Louis L'Amour's The Walking Drum is a native of Brittany, and extensively references the culture of Armorica in the 12th century.

Footnotes

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. "Aremorica"; The Free Dictionary, s.v. "Aremorica".

- ↑ The Irish form is ar mhuir, the Manx is er vooir, and the Scottish form air mhuir. However, in these languages the phrase means "on the sea", as opposed to ar thír or ar thalamh/ar thalúin (er heer/er haloo, air thìr/air thalamh) "on the land".

- ↑ History Compass : Home Archived April 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Caesar, De Bello Gallico ii.4.

- ↑ "Coinage in Iron Age Armorica", Studies in Celtic Coinage, 2 (1994)

- ↑ Leon Fleuriot's primarily linguistic researches in Les Origines de la Bretagne, emphasizes instead the broader influx of Britons into Roman Gaul that preceded the fifth-century collapse of Roman power.

- ↑ Procopius, in History of the Wars, viii, 20, 6-14.

- ↑ K. Jackson, Language and History in Early Britain Edinburgh, 1953:14f.

- ↑ Martin Henig, British Archaeology, 2003, review of The British Settlement of Brittany by Pierre-Roland Giot, Philippe Guigon & Bernard Merdrignac

- ↑ C.E.V. Nixon, "Relations Between Visigoths and Romans in Fifth Century Gaul", in John Drinkwater, Hugh Elton (eds) Fifth-Century Gaul: A Crisis of Identity?, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 69

- ↑ Keys, David (1 April 1993). "Asterix's home village is uncovered in France: Archaeological dig reveals fortified Iron Age settlement on 10-acre site". The Independent. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Mowat, Farley. The Farfarers: Before the Norse. Key Porter Books, Limited. ISBN 978-1-883642-56-3.

See also

- Armoricani

- Armorican

- Plomodiern Parish close

- Saxon shore (Tractus armoricanus)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Armorica. |

- Martin Henig, review in British Archaeology 72(September 2003)

- John Hooker - Coriosolite (Armorican) coinage and classification

Coordinates: 48°10′00″N 1°00′00″W / 48.1667°N 1.0000°W