Assimilation and contrast effects

The assimilation effect is a frequently observed bias in evaluative judgments towards the position of a context stimulus.[1] When an assimilation effect occurs, judgments and contextual information are correlated positively, i.e. a positive context stimulus results in a positive judgment, whereas a negative context stimulus results in a negative judgment.[2] Assimilation effects are different from contrast effects, where a negative correlation between judgments and contextual information is observed.

Factors determining assimilation and contrast effects

Assimilation effects are more likely when the context stimulus and the target stimulus have characteristics that are quite close to each other. In their priming experiments, Herr, Sherman and Fazio (1983)[3] found assimilation effects when subjects were primed with moderate context stimuli. The more specific or extreme the context stimuli are in comparison to the target stimulus, the more likely contrast effects are to occur.

However, these are just likelihoods that can serve as indicators for the occurrence of assimilation effects. Depending on how the individual categorizes information, contrast effects can occur as well. A more specific model to predict assimilation and contrast effects with differences in categorizing information is the inclusion/exclusion model developed by Norbert Schwarz and Herbert Bless.[4]

The inclusion/exclusion model

The inclusion/exclusion model of assimilation and contrast effects explains the mechanism through which assimilation and contrast effects occur.[5] The model assumes that in feature-based evaluative judgments of a target stimulus, people have to form two mental representations: A representation of the target stimulus and one of a standard of comparison to evaluate the target stimulus. Focusing on the dependence of the context, the construal of these mental representations from accessible information (i.e. information that comes to mind in that specific moment and draws attention) results in either assimilation or contrast effects. When using the accessible information for constructing the representation of the target, an assimilation effect results, whereas accessible information that is constructed in the mental representation of the standard of comparison leads to contrast effects.

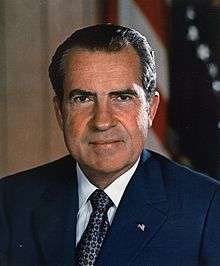

By way of illustration, in their research on the perceived trustworthiness of politicians, Schwarz & Bless[6] either primed their subjects with scandal-ridden politicians (e.g. Richard Nixon) or primed them not. When subsequently asked for the evaluation of politicians' trustworthiness in general, subjects under the priming condition evaluated politicians in general as less trustworthy than subjects did in the condition without priming. This demonstrates the inclusion of scandal-ridden politicians in the representation of the target stimulus and depicts an assimilation effect. The accessible information of politicians' scandals led to a less favorable evaluation of politicians' trustworthiness in general, or in other words, was included in the representation of the target stimulus.

In contrast, such inclusion after the priming did not occur when subjects were subsequently asked for the trustworthiness of other specific politicians. In this case the priming led to a more favorable evaluation of the other politician's trustworthiness than under the condition without priming. This demonstrates a contrast effect, because the accessible information was excluded from the representation of the target stimulus (e.g. Richard Nixon is not Newt Gingrich) and therefore constructed in the mental representation of the standard of comparison.

Consequently, the same accessible information can result in assimilation or contrast effects, depending on how it is categorized.

Simultaneous assimilation and successive contrast

Assimilation effects have been seen to behave quite differently when objects are presented simultaneously, rather than successively. A series of studies found assimilation effects when asking participants to rate the attractiveness of faces that were presented simultaneously. When an unattractive face was presented next to an attractive face, the unattractive face became more attractive, while the rating of the attractive face did not change. In other words, placing oneself next to an attractive person would make you more attractive, as long as you are less attractive than that person to begin with. These effects remained even if the number of faces presented increased and remained over two minutes after the context stimulus (the attractive face) was removed.

Relating these findings to the Inclusion/Exclusion Model above, if we take the classic Richard Nixon example, if Nixon (a scandal ridden politician) is presented side by side Newt Gingrich, then rather than the type of assimilation effect exhibited when they are presented successively (Newt becomes more trustworthy), when presented simultaneously Nixon becomes more trustworthy, and the trustworthiness of Newt doesn't change. These studies also supported the Inclusion/Exclusion Model, showing that contrast effects appeared if attractive faces were presented successively before presenting an unattractive face; in this case the unattractive face was rated as even more unattractive.[7][8]

Examples of assimilation and contrast effects

Assimilation effects arise in many fields of social cognition, for example in the field of judgment processes or in social comparison.

Whenever researchers conduct attitude surveys and design questionnaires, they have to take judgment processes and the resulting assimilation effects into account. Assimilation effects (as well as contrast effects) may arise through the sequence of questions. Previously asked specific questions may influence subsequent more general ones:

Many researchers found assimilation effects when deliberately manipulating the order of general and specific questions.[9][10] When they first asked participants how happy they were with their dating or how satisfied they were with their relationship (a specific question that functions as a moderate context stimulus) and subsequently asked the participants how happy they were with their life in general (general question), they found assimilation effects. The specific question of their happiness with dating or satisfaction with their relationship made specific information accessible, that was further included as representation of the subsequent general question as target stimulus. Thus, by the time the participants were happy with their dating or satisfied with their relationship, they also reported being happier with their life in general. Similarly, when the participants were unhappy with their dating or dissatisfied with their relationships, they indicated being as well unhappier with their life in general. This effect did not occur when asking the general question in the first place.

The term assimilation effect appears in the field of social comparison research as well. Complementary to the previously stated definition, the term describes the effect of a felt psychological closeness of social surroundings that influence the current self-representation and self-knowledge.

See also

- Anchoring

- Attitude polarization

- Confirmation bias § Biased interpretation

- Contrast effect, for a more general overview of the subject, including perception

- Distinction bias

- Norbert Schwarz § Categorization and Judgment

- Priming

References

- ↑ Bless, H., Fiedler, K., & Strack, F. (2004). Social Cognition: How individuals construct social reality. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

- ↑ Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (2007). Mental construal processes: The inclusion/exclusion model. In D. A. Stapel & J. Suls (Eds.), Assimilation and contrast in Social Psychology (pp. 119–141). New York: Psychology Press.

- ↑ Herr, P. M., Sherman, S. J., & Fazio, R. H. (1983). On the Consequences of Priming: Assimilation and Contrast Effects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 323–340.

- ↑ Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992a). Assimilation and contrast effects in attitude measurement: An inclusion/exclusion model. Advances in Consumer Research, 19, 72–77.

- ↑ Bless, H., & Schwarz, N. (2010). Mental Construal and the Emergence of Assimilation and Contrast Effects: The Inclusion/Exclusion Model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 319–373.

- ↑ Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992b). Scandals and the public's trust in politicians: Assimilation and contrast effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 574–579.

- ↑ Wedell, D. H., Parducci, A., & Geiselman, R. E. (1987). A formal analysis of ratings of physical attractiveness: Successive contrast and simultaneous assimilation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23(3), 230-249c

- ↑ Geiselman, R. E., Haight, N. A., & Kimata, L. G. (1984). Context effects on the perceived physical attractiveness of faces. Journal of experimental social psychology, 20(5), 409-424

- ↑ Schwarz, N., Strack, F., & Mai, H.P. (1991). Assimilation and contrast effects in part-whole question sequences: A conversational logic analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55, 3–23.

- ↑ Strack, F. Martin, L. L., & Schwarz, N. (1987). The context paradox in attitude surveys: Assimilation or contrast?. Mannheim (Germany): ZUMA.

Bibliography

- Colman, Andrew M. (2008). "Assimilation-contrast theory". A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199534067.

- Oyserman, Daphna; Elmore, Kristen; Smith, George (2012). "Self, Self-Concept, and Identity" (PDF). In Leary, Mark R.; Tangney, June Price. Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781462503056.