Athy

| Athy Baile Átha Í | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

|

River Barrow, Crom-a-Boo Bridge and White's Castle | |

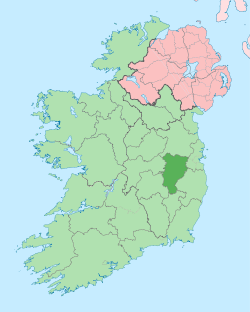

Athy Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 52°59′31″N 6°59′13″W / 52.99197°N 6.98698°WCoordinates: 52°59′31″N 6°59′13″W / 52.99197°N 6.98698°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Kildare |

| Elevation | 71 m (233 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 10,490 |

| Time zone | WET (UTC+0) |

| • Summer (DST) | IST (WEST) (UTC-1) |

| Irish Grid Reference | S680939 |

| Website |

www |

Athy (/əˈθaɪ/;[1] Irish: Baile Átha Í, meaning "town of the ford of Ae") is a market town at the meeting of the River Barrow and the Grand Canal in south-west County Kildare, Ireland, 72 kilometres southwest of Dublin.

A population of 10,490 (2011 Census preliminary results)[2] makes it the sixth largest town in Kildare and the 50th largest in the Republic of Ireland, with a growth rate of 58% since the 2002 census. From the first official records in 1813 (population 3,192) until 1891 (population 4,886) and again in 1926–46 and 1951–61 Athy was the largest town in Kildare. In 1837 the population was 4,494.[3]

It has recently entered the news because of a suspect device found by a member of the public on 15 November 2016.[4]

History

.jpg)

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1813 | 3,192 | — |

| 1821 | 3,693 | +15.7% |

| 1831 | 4,494 | +21.7% |

| 1841 | 4,698 | +4.5% |

| 1851 | 3,873 | −17.6% |

| 1861 | 4,124 | +6.5% |

| 1871 | 4,510 | +9.4% |

| 1881 | 4,181 | −7.3% |

| 1891 | 4,886 | +16.9% |

| 1901 | 3,599 | −26.3% |

| 1911 | 3,535 | −1.8% |

| 1926 | 3,460 | −2.1% |

| 1936 | 3,628 | +4.9% |

| 1946 | 3,639 | +0.3% |

| 1951 | 3,752 | +3.1% |

| 1956 | 3,948 | +5.2% |

| 1961 | 3,842 | −2.7% |

| 1966 | 4,069 | +5.9% |

| 1971 | 4,654 | +14.4% |

| 1979 | 4,755 | +2.2% |

| 1981 | 5,565 | +17.0% |

| 1986 | 5,449 | −2.1% |

| 1991 | 5,204 | −4.5% |

| 1996 | 5,306 | +2.0% |

| 2002 | 6,058 | +14.2% |

| 2006 | 7,943 | +31.1% |

| 2011 | 10,490 | +32.1% |

| [5][6][7][8][9] | ||

Athy or Baile Átha Í is named after a 2nd-century chieftain, Ae, who is said to have been killed on the river crossing, thus giving the town its name "the town of Ae's ford". The earliest maps show development on the river Barrow i the area, Ptolemy's map of Ireland circa 150AD clearly names the Rheban district as Rheba.

The town developed from a 12th-century Anglo-Norman settlement to an important stronghold on the local estates of the FitzGerald earls of Kildare, who built and owned the town for centuries.

The Confederate Wars of the 1640s were played out in many arenas throughout Ireland and Athy – for a period of eight years – was one of the centres of war involving the Royalists, Parliamentarians and the Confederates. The town was bombarded by cannon fire many times and the Dominican Monastery, the local castles and the town's bridge (dating from 1417) all succumbed to the destructive forces of the cannonball. The current bridge, the Crom-a-Boo Bridge, was built in 1796.[10]

The first town charter dates from 1515 and the town hall was constructed in the early 18th century. The completion of the Grand Canal in 1791, linking here with the River Barrow, and the arrival of the railway in 1846, illustrate the importance of the town as a commercial centre. From early on in its history Athy was a garrison town loyal to the Crown. English garrisons stayed in the barracks in Barrack Lane after the Crimean War and contributed greatly to the town's commerce. Home for centuries to English soldiers, Athy gave more volunteer soldiers to the Great War of 1914–18 than any other of similar sized town in Ireland.

A centre of Hiberno-English

Athy has evolved as a centre for Hiberno-English, the mix of the Irish and English language traditions. A dialect starting with old Irish beginnings, evolved through Norman and English influences, dominated by a church whose first language was Latin and educated through Irish. Athy in particular was a mixing pot of languages that led to modern Hiberno-English. Positioned at the edge of the Pale, sandwiched between the Irish and English speaking partitions, Athy traded language between the landed gentry, the middle class merchants, the English working class garrison soldiers and the local peasantry. Many locals words borrow from the Irish tradition, such as "bokety", "fooster" or "sleeveen", while words like "kip", "cop-on" or even "grinds" have their origins in Old or Middle English.

This tradition of spoken word led to a lyrical approach to composition and perhaps explains the disproportionate number of writers Athy has produced. Athy becomes subject and object of creative endeavours – the traditional folk song, "Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye", is a prime example. Other songs in this tradition include "Lanigan's Ball" and "Maid of Athy".[11] Another song of note from the area is called "The Curragh Of Kildare", the first song collected by Robbie Burns.[12] Athy is also the surname of a minor character in James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, who tells Stephen Dedalus, the protagonist, that they both have strange surnames and makes a joke about County Kildare being like a pair of breeches because it has Athy in it. Athy is referenced by Patrick Kavanagh in his poem Lines Written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin: "And look! a barge comes bringing from Athy/And other far-flung towns mythologies."[13]

The birth of motor racing

On Thursday, 2 July 1903 the Gordon Bennett Cup ran through Athy. It was the first international motor race to be held in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, an honorific to Selwyn Edge who had won the 1902 event in Paris driving a Napier. The Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland wanted the race to be hosted in the British Isles, and their secretary, Claude Johnson (managing director of C.S. Rolls & Co), suggested Ireland as the venue because racing was illegal on British public roads. The editor of the Dublin Motor News, Richard J. Mecredy, suggested an area in County Kildare and letters were sent to 102 Irish MPs, 90 Irish peers, 300 newspapers, 34 chairmen of county and local councils, 34 County secretaries, 26 mayors, 41 railway companies, 460 hoteliers, 13 PPs, plus the Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin, Patrick Foley, who pronounced himself in favour. Local laws had to be adjusted, ergo the 'Light Locomotives (Ireland) Bill' was passed on 27 March 1903. Kildare and other local councils drew attention to their areas, whilst Queen's County declared That every facility will be given and the roads placed at the disposal of motorists during the proposed race. Eventually Kildare was chosen, partly on the grounds that the straightness of the roads would be a safety benefit.

The route consisted of two loops that comprised a figure of eight. The first was a 52-mile (84 km) loop that included Kilcullen, The Curragh, Kildare, Monasterevin, Stradbally and Athy, followed by a 40-mile (64 km) loop through Castledermot, Carlow and Athy again. The race started at the Ballyshannon cross-roads (53°05′07″N 6°49′12″W / 53.0853°N 6.82°W) near Calverstown on the contemporary N78 heading north, then followed the N9 north; the N7 west; the N80 south; the N78 north again; the N9 south; the N80 north; the N78 north again. Competitors were started at seven-minute intervals and had to follow bicycles through the 'control zones' in each town. The 328 miles (528 km) race was won by the famous Belgian Camille Jenatzy, driving a Mercedes in German colours.[14][15] This race is still celebrated today.

British racing green

Britain had to choose a different colour to its usual national colours of red, white and blue, as these had already been taken by Italy, Germany and France respectively. Red was also stated as the colour for American cars in the 1903 Gordon Bennett Cup. As a compliment to Ireland, the British team chose to race in shamrock green which thus became known as British racing green, although the winning Napier of 1902 had in fact been painted olive green.[14][16][17][18][19]

Historic places of interest

Athy's courthouse was designed by Frederick Darley and built in the 1850s. The building was originally the town's corn exchange.[20]

- O'Brien's Bar:

The town's pub, Frank O'Brien's Bar, is considered a tourist attraction and was voted one of the top ten Irish bars in the Sunday Tribune in 1999.[21][22] Hardware merchants Griffin Hawe now occupy the town's 6 ft. wide and 12 ft. high 18th century cockpit.

- Kilkea Castle: Kilkea Castle is located just 5 km (3.1 mi) northwest of Castledermot, near the village of Kilkea. It was a medieval stronghold of the FitzGeralds, Earls of Kildare.

- Whites Castle: Whites Castle was built in 1417 by Sir John Talbot, Viceroy of Ireland, to protect the bridge over the Barrow and the inhabitants of the Pale. Built into the wall on either side of the original entrance doorway are two sculptured slabs. On the right of the former doorway is the Earl of Kildare's coat of arms, signifying the Earl's ownership of the castle in former days. The slab on the left bears the date 1573, and the name Richard Cossen, Sovereign of Athy.

- The Moat of Ardscull: The Moat of Ardscull is the focal point of local legend about "little people". Assumed to have been built in the late 12th or 13th century, the first clear reference to the moat is in 1654 when the "Book of General Orders" noted a request from the inhabitants of County Kildare for the State to contribute £30 "towards the finishing of a Fort that they have built at the Moate of Ardscull".[23]

- Athy Workhouse: St Vincent's Hospital was formally the Athy Workhouse. The Athy Poor Law Union was formally declared on 16 January 1841 and covered an area of 252 square miles. The new Athy Union workhouse was erected in 1842–43 on a 6.5-acre site half a mile north-west of Athy. Designed by the Poor Law Commissioners' architect George Wilkinson, the building was based on one of his standard plans to accommodate 600 inmates.[24]

- St. Michael's Church: Originally built in the fourteenth century. Some of the vestry and side walls have disappeared, but there is still some of the original church remaining. A small cross lies within the church grounds and it is said that a cross or font is buried in a grave, within the ruins. There was at one time an arch that stood in front of St. Michael's but during some renovations many years ago, this was taken down.

- Quaker Meeting House: Built in 1780 and standing on Meeting Lane. The first Quakers in Athy may have been Thomas Weston and his wife who in 1657 "received the truth" from Thomas Loe, an English preacher, who was visiting some friends in County Carlow (and who later influenced William Penn).[25] They were soon joined by the Bonnett family, the first Quaker family to settle in Carlow. A Quaker meeting was settled in Athy by 1671, the year in which Athy was included in the list of towns where the Leinster Province Meeting was held. The local Quakers met for worship once a week on Wednesdays, and every month a district meeting was held in Carlow to transact church business. Athy, as part of the Carlow district, also sent delegates to the Province's quarterly meetings.

- The Dominican Church: The Dominicans arrived in Athy in 1253 or 1257.[26] They settled on the eastern bank of the Barrow, first in thatched huts of wood and clay, later in a stone priory and church dedicated to St Peter Martyr, one of the earliest saints of the Order. Today, it is the opposite bank of the river that is dominated by the Dominican Church. In November 2015 the Dominicans finally left Athy due to a lack of friars,[27] and the church and lands have been bought by Kildare County Council.[28]

- Athy Heritage Centre: Athy contains the only permanent exhibition on Ernest Shackleton, who was born at Kilkea House. The exhibit is housed in the heritage centre, which has a collection of artefacts from Athy's past as well as artefacts from Shackleton's expeditions. Among the most impressive is a scale model of the Endurance. Each year the Centre arranges and hosts the Shackleton Autumn School, with speakers from around the world to speak on different aspects of Antarctica and Shackleton's life.[29]

- Aontas Ogra: The local youth club in Athy which was set up, originally, as an Irish-speaking revival in 1956. It soon developed into a youth club and was the first boy-girl youth club in Ireland. It is still well-established to this day as an independent youth club in Kildare and is located now, beside ARCH on the Ballylinan road.

Aontas Ogra Logo

Aontas Ogra Logo - 1798 Rebellion Memorial: This landmark is located in Emily Square and is dedicated to Athy's role in the 1798 Rebellion, as well as a memorial to the people that died during the famine.

Notable people

- Philip Crosthwaite, businessman and politician

- Paul Cullen, Archbishop of Dublin and the first Irish cardinal

- Eric Donovan, Irish boxer and European championships bronze medal winner

- Lord Edward FitzGerald, politician and revolutionary

- William Russell Grace, businessman and politician

- John Holland, Victoria Cross recipient

- Mary Leadbeater, author and diarist

- Thomas Lee, soldier and assassin

- Jack Lukeman, musician and record producer

- George Lyttleton-Rogers, tennis player and coach

- John Minihan, photographer

- John MacKenna, playwright and novelist

- Liam O'Flynn, uilleann piper

- Sir Ernest Shackleton, polar explorer

- Zoltan Zinn-Collis, Slovakian survivor of the Holocaust, author of Final Witness. He was one of only five living survivors of the Holocaust in Ireland. He died in his Athy home in Ireland on December 10, 2012.

Transport

Road

The town is located on the N78 national secondary road where it crosses the R417 regional road. In 2010 the N78 was re-aligned so that it no longer heads from Athy towards Kilcullen and Dublin via Ardscull, but now connects with the M9 motorway near Mullamast. The old Athy-Kilcullen section of the road previously known as the N78 is now the R418.

Rail

Athy is connected to the Irish rail network via the Dublin–Waterford main line. Athy railway station opened on 4 August 1846 and closed for goods traffic on 6 September 1976.[30] There is a disused siding to the Tegral Slate factory (formerly Asbestos Cement factory). This is all that is left of the former branch to Wolfhill colliery. This side line was built by the United Kingdom government in 1918 due to wartime shortage of coal in Ireland. The concrete bridge over the River Barrow on this branch is one of the earliest concrete railway under bridges in Ireland.

Bus

Bus Éireann route 7 and JJ Kavanagh's route 717 also provide frequent services to Athy.[31] Bus Éireann route 130 also serves the town but in one direction only. South Kildare Community Transport also operate two routes from the town serving outlying villages and rural areas[32]

Sport

- Athy GAA was formed in 1887. The playing pitch in the early days changed several times until 1905. In 1905 the club rented a field at the Dublin road from the South Kildare Agricultural Society – the present day Geraldine Park. The club had the initiative in those early days to erect a paling around the pitch and were the first club in Leinster to do so. This initiative and club's effort were rewarded when the All-Ireland finals were played in Athy in 1906.

- Athy Rugby Club was founded in 1880 and five time winner of the Leinster Towns Cup.

- Athy Golf Club was formed in 1906 as a nine-hole course and was extended to 18 holes in 1993. The course had a par of 71 and it extended to 6,400 yards from the medal tees. It is situated at Geraldine, a mile from town on the Kildare Road.[33]

- Tri-Athy is a triathlon event held in Athy on the June Bank Holiday weekend.[34]

- Athy Tennis Club has over 120 members[35]

- Athy Town AFC[36]

- St Michael's Boxing Club

- Athy Rowing Club

- K-Leisure Swimming Pool

- A skate park has been implemented in recent years.

Twinning

In 2003, the town became twinned with the French town of Grandvilliers in the Oise-Picardy département. The French twinning committee is named "La Balad'Irlandaise", and official visits take place every two years, while musical and student exchanges take place more regularly.

See also

- List of abbeys and priories in Ireland (County Kildare)

- List of towns and villages in Ireland

- Market Houses in Ireland

- Duke of Leinster

Further reading

- A Short History of Athy (1999) by Frank Taaffe, published by Athy Heritage Company Limited

References

- ↑ Athy. (2001). In Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary . Retrieved 17 February 2007. The dictionary does not use IPA notation, but the pronunciation given, \ə-ˈthī\, is apparently equivalent to IPA /əˈθaɪ/.

- ↑ , To find the population of Athy, you must add Athy East Urban, Athy West Urban, Athy Rural (Part Rural), and Athy Rural (Part Urban).

- ↑ Entry for Athy in Lewis Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837)

- ↑ "Viable bomb found in Kildare". 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ↑ Census for post 1821 figures.

- ↑ http://www.histpop.org

- ↑ "NISRA – Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (c) 2013". Nisranew.nisra.gov.uk. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x.

- ↑ Taaffe, Frank (23 May 1996). "Athy Eye on the Past: The Bridge of Athy". Athyeyeonthepast.blogspot.ie.

- ↑ Christy Moore, Paddys on the Road. Mercury Records 1969, produced by Dominic Behan

- ↑ History Ireland http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/nicknames-a-directory-of-occupations-geographies-prejudices-and-habits/

- ↑ "Patrick Kavanagh, Lines Written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin". Tcd.ie.

- 1 2 Leinster Leader, Saturday, 11 April 1903

- ↑ Bleacher report, The Birth of British motor racing

- ↑ Circle Genealogic and Historic Champanellois Archived 5 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Forix 8W – Britain's first international motor race by Brendan Lynch, based on his Triumph of the Red Devil, the 1903 Irish Gordon Bennett Cup Race. 22 October 2003

- ↑ The Gordon Bennett races – the birth of international competition. Author Leif Snellman, Summer 2001

- ↑ "Leinster Leader April 1903 – Review of the coming Gordon Bennett Race". Kildare.ie. 11 April 1903.

- ↑ "Athy Courthouse : HERITAGE : Courts Service of Ireland". Courts.ie. 21 June 2001.

- ↑ Sunday Tribune 3 October 1999

- ↑ "O'Briens'". Obriensbar.com.

- ↑ "Kilmead – Moat of Ardscull". Kildare.ie.

- ↑ Peter Higginbotham. "The Workhouse in Athy, Co. Kildare". Workhouses.org.uk.

- ↑ "Thomas Loe (British minister)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Dominicans Ireland – Athy". Dominicans.ie. 17 March 1965.

- ↑ "Dominicans bid sad farewell to Athy foundation". Catholic Ireland. 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "Press Release - Athy Multipurpose Community Facility". Kildare County Council. 1 February 2016.

- ↑ "Athy Heritage Centre-Museum". Athyheritagecentre-museum.ie. 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Athy station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ↑ BE Timetable Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://skct.ie/Athy_Newbridge%20Timetable%20June%202013.pdf

- ↑ Home. "Welcome to Athy Golf Club". Athygolfclub.com.

- ↑ http://www.triathy.com/

- ↑ "athy tennis court sport kildare". Athy Tennis Club.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Athy. |

- Athy, Kildare County Council

- TriAthy website (triathlon information)

- Cuan Mhuire Web Site

- Eye On The Past column by local historian Frank Taaffe

- Official site of Grandvilliers twinning committee

- Official site of Athy Rugby Football Club

- Aontas Ogra Official Website

- Athy Film Club

- AthyLive.com – Information about community groups and upcoming events

- – Local free monthly glossy magazine also available as a paper edition

- Athy Town AFC

- St. Michaels Roman Catholic Parish, Athy