Bargaining

Bargaining or haggling is a type of negotiation in which the buyer and seller of a good or service debate the price and exact nature of a transaction. If the bargaining produces agreement on terms, the transaction takes place. Bargaining is an alternative pricing strategy to fixed prices. Optimally, if it costs the retailer nothing to engage and allow bargaining, s/he can divine the buyer's willingness to spend. It allows for capturing more consumer surplus as it allows price discrimination, a process whereby a seller can charge a higher price to one buyer who is more eager (by being richer or more desperate). Haggling has largely disappeared in parts of the world where the cost to haggle exceeds the gain to retailers for most common retail items. However, for expensive goods sold to uninformed buyers such as automobiles, bargaining can remain commonplace.

Dickering refers to the same process, albeit with a slight negative (petty) connotation.

Bargaining is also the name chosen for the third stage of the Kübler-Ross model (commonly known as the stages of dying), even though it has nothing to do with price negotiations.

Where it takes place

Not all transactions are open to bargaining. Both religious beliefs and regional custom may determine whether or not the seller is willing to bargain.

Regional differences

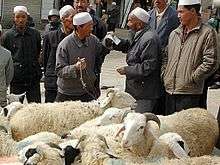

In North America and Europe bargaining is restricted to expensive or one-of-a-kind items (automobiles, antiques, jewelry, art, real estate, trade sales of businesses) and informal sales settings such as flea markets and garage sales. In other regions of the world, bargaining may be the norm, even for small commercial transactions.

In Indonesia and elsewhere in Asia, locals haggle for goods and services everywhere from street markets to hotels. Even children learn to haggle from a young age. Participating in that tradition can make foreigners feel accepted.[1] On the other hand, in Thailand, haggling seems to be softer than the other countries due to Thai culture, in which people tend to be humble and avoiding argument.[2] However, haggling for food items is strongly discouraged in Southeast Asia and is considered an insult, because food is seen as a common necessity that is not to be treated as a tradable good.[3]

In almost all large complex business negotiations, a certain amount of bargaining takes place. One simplified 'western' way to decide when it's time to bargain is to break negotiation into two stages: creating value and claiming value. Claiming value is another phrase for bargaining. Many cultures take offence when they perceive the other side as having started bargaining too soon. This offence is usually as a result of their wanting to first create value for longer before they bargain together. The Chinese culture by contrast places a much higher value on taking time to build a business relationship before starting to create value or bargain. Not understanding when to start bargaining has ruined many an otherwise positive business negotiation.[4]

In areas where bargaining at the retail level is common, the option to bargain often depends on the presence of the store's owner. A chain store managed by clerks is more likely to use fixed pricing than an independent store managed by an owner or one of owner's trusted employees. [5]

The store's ambiance may also be used to signal whether or not bargaining is appropriate. For instance, a comfortable and air-conditioned store with posted prices usually does not allow bargaining, but a stall in a bazaar or marketplace may. Supermarkets and other chain stores almost never allow bargaining. However, the importance of ambiance may depend on the cultural commitment to bargaining. In Israel, prices on day-to-day items (clothing, toiletries) may be negotiable even in a Western style store manned by a clerk.

Theories

Behavioral theory

The personality theory in bargaining emphasizes that the type of personalities determine the bargaining process and its outcome. A popular behavioral theory deals with a distinction between hard-liners and soft-liners. Various research papers refer to hard-liners as warriors, while soft-liners are shopkeepers. It varies from region to region. Bargaining may take place more in rural and semi-urban areas than in a metro city.

Game theory

Bargaining games refer to situations where two or more players must reach agreement regarding how to distribute an object or monetary amount. Each player prefers to reach an agreement in these games, rather than abstain from doing so. However, each prefers that the agreement favour their interests. Examples of such situations include the bargaining involved in a labour union and the directors of a company negotiating wage increases, the dispute between two communities about the distribution of a common territory, or the conditions under which two countries agree on nuclear disarmament. Analyzing these kinds of problems looks for a solution that specifies which component in dispute corresponds to each party involved.

Players in a bargaining problem can bargain for the objective as a whole at a precise moment in time. The problem can also be divided so that parts of the whole objective become subject to bargaining during different stages.

In a classical bargaining problem the result is an agreement reached between all interested parties, or the status quo of the problem. It is clear that studying how individual parties make their decisions is insufficient for predicting what agreement will be reached. However, classical bargaining theory assumes that each participant in a bargaining process will choose between possible agreements, following the conduct predicted by the rational choice model. It is particularly assumed that each player's preferences regarding the possible agreements can be represented by a von Neumann–Morgenstern utility theorem function.

Nash [1950] defines a classical bargaining problem as being a set of joint allocations of utility, some of which correspond to what the players would obtain if they reach an agreement, and another that represents what they would get if they failed to do so.

A bargaining game for two players is defined as a pair (F,d) where F is the set of possible joint utility allocations (possible agreements), and d is the disagreement point.

For the definition of a specific bargaining solution it is usual to follow Nash's proposal, setting out the axioms this solution should satisfy. Some of the most frequent axioms used in the building of bargaining solutions are efficiency, symmetry, independence of irrelevant alternatives, scalar invariance, monotonicity, etc.

The Nash bargaining solution is the bargaining solution that maximizes the product of an agent's utilities on the bargaining set.

The Nash bargaining solution, however, only deals with the simplest structure of bargaining. It is not dynamic (failing to deal with how pareto outcomes are achieved). Instead, for situations where the structure of the bargaining game is important, a more mainstream game theoretic approach is useful. This can allow players' preferences over time and risk to be incorporated into the solution of bargaining games. It can also show how the details can matter. For example, the Nash bargaining solution for Prisoners' Dilemma is different from the Nash equilibrium.

Bargaining and posted prices in retail markets

Retailers can choose to sell at posted prices or allow bargaining: selling at a public posted price commits the retailer not to exploit buyers once they enter the retail store, making the store more attractive to potential customers, while a bargaining strategy has the advantage that it allows the retailer to price discriminate between different types of customer.[6] In some markets, such as those for automobiles and expensive electronic goods, firms post prices but are open to haggling with consumers. When the proportion of haggling consumers goes up, prices tend to rise.[7]

Processual theory

This theory isolates distinctive elements of the bargaining chronology in order to better understand the complexity of the negotiating process. Several key features of the processual theory include:

- Bargaining range

- Critical risk

- Security point

Integrative theory

Integrative bargaining (also called "interest-based bargaining," "win-win bargaining") is a negotiation strategy in which parties collaborate to find a "win-win" solution to their dispute. This strategy focuses on developing mutually beneficial agreements based on the interests of the disputants. Interests include the needs, desires, concerns, and fears important to each side. They are the underlying reasons why people become involved in a conflict.

"Integrative refers to the potential for the parties' interests to be [combined] in ways that create joint value or enlarge the pie." Potential for integration only exists when there are multiple issues involved in the negotiation. This is because the parties must be able to make trade-offs across issues in order for both sides to be satisfied with the outcome.[8]

Narrative theory

A very different approach to conceptualizing bargaining is as co-construction of a social narrative, where narrative, rather than economic logic drives the outcome.

Automated bargaining

When a bargaining situation is complex, finding Nash equilibrium is difficult using game theory. Evolutionary computation methods have been designed for automated bargaining, and demonstrated efficient and effective for approximating Nash equilibrium.[9]

Anchor Pricing

Anchor price is the first call made during a bargain. The first call sets a condition of pricing biased towards the first caller.

See also

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bargaining. |

References

- ↑ Sood, Suemedha. "The art of haggling". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Putthiwanit, C. & Santipiriyapon, S. (2015). Apparel bargaining attitude and bargaining intention (intention to re-bargain) driven by culture of Thai and Chinese consumers, Journal of Community Development and Life Quality, 3(1), 57-67

- ↑ "How to Haggle in Southeast Asia". 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ "Chinese Negotiation - Negotiation Experts". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ "Bargain Hunting on the Rise in India". digitaljournal. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Wang, Ruqu (1 December 1995). "Bargaining versus posted-price selling". European Economic Review. 39 (9): 1747–1764. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)90043-8. Retrieved 10 September 2016 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Gill, David and Thanassoulis, John (2009). The impact of bargaining on markets with price takers: Too many bargainers spoil the broth, European Economic Review, 53(6), 658-674 SSRN 1127627

- ↑ "?".

- ↑ "?". Automated Bargaining project at University of Essex.

- An explanation of the narrative theory of bargaining Ribbonfarm.com

Further reading

The articles in the list were not used in the creation of this article, but provide further background information on the topic. If you are reading this article, and have access to these sources, please consider editing this article and adding references from these sources. -- if you've added a reference, please remove the article from this section.

- Uchendu, Victor. "Some Principles of Haggling in Peasant Markets." in Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Oct., 1967), pp. 37–50.

- Definitions: Bargaining, and Bargaining Zone.

- Psychological perspective of when we bargain in desperation.

- Ethnographic analysis of tourists haggling for souvenirs: Gillespie, A. (2007). In the other we trust: Buying souvenirs in Ladakh, North India, Academia.edu.

- On bargaining theory: Abhinay Muthoo. "Bargaining Theory with Applications", Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- On automated bargaining: Tim Gosling, Nanlin Jin & Edward Tsang, Games, supply chains and automatic strategy discovery using evolutionary computation, in J-P. Rennard (Eds.), Handbook of research on nature-inspired computing for economics and management, Vol II, Chapter XXXVIII, Idea Group Reference, 2007, 572-588