Battle of Beauport

| Battle of Beauport | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seven Years' War French and Indian War | |||||||

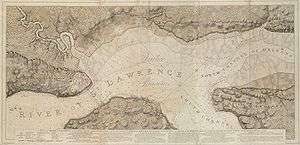

A 1777 map depicting the military positions of the French and British during the Siege of Quebec | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James Wolfe | Marquis de Montcalm | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000 regulars | ~10,000 regulars and militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

210 killed 233 wounded[1] | 60 dead or wounded[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Beauport, also known as the Battle of Montmorency, fought on 31 July 1759, was an important confrontation between the British and French Armed Forces during the Seven Years' War (also known as the French and Indian War and the War of Conquest) of the French province of Canada. The attack conducted by the British against the French defense line of Beauport, some five kilometres (3.1 mi) east of Quebec was checked, and the British soldiers of General James Wolfe retreated with 443 casualties and losses.

Background

The French and Indian War campaigns of 1758 were successful for the British, who had sent more than 40,000 men against New France and made key gains by capturing Louisbourg and destroying Fort Frontenac, although their primary thrust was stopped by French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm in the Battle of Carillon. William Pitt continued the aggressive policy in 1759, again organizing large campaigns aimed at the heartland of New France, the Canadien communities of Quebec and Montreal on the St. Lawrence River. For the campaign against Quebec, General James Wolfe was given command of an army of about 7,000 men.

Beauport

When he arrived before Quebec on 26 June, Wolfe observed that the northern shore of the St. Lawrence River around Beauport (the Beauport shore), the most favourable site for the landing of troops, was strongly defended by the French, who had built entrenchments on high ground, redoubts and floating batteries. Wolfe consequently had to devise a plan involving a landing on some other location of the shore. The search for the best site kept him busy for weeks.

Montmorency camp

On the night of 8th or 9th July, British forces landed on the north shore, some 1.2 km (1 mi) east of the Montmorency Falls, east of where the French west-east defence line ended, at the mouth of the Montmorency River. Wolfe landed first, leading the Louisbourg grenadiers, who were followed by the brigade commanded by George Townshend. The landing met no opposition from the French.[3] James Murray, at the head of a part of his brigade, joined Wolfe and Townshend on 10 July. A camp was set up near the landing site. Wolfe ordered the construction of a battery to defend the camp, as well as rafts and floating batteries in anticipation of an attack on the French line.[4]

Plan of attack

After establishing the Montmorency camp, Wolfe explored various plans of attack, and chose his plan on 28 July. He has two main plans.

The first plan which Wolfe mentioned in his journal and the correspondence with his officers is that of 16 July. In a letter to Brigadier Robert Monckton, Wolfe wrote that he hoped to capture one of the French redoubts, the second one counting from the east end of the Beauport line, in order to force the enemy out of their entrenchments. The plan involved an attack by the Navy, an important landing force transported from Île d'Orléans, as well as a body of troops crossing the river Montmorency on rafts and marching westward to the battle site. At the same time, the brigade commanded by Monckton was to land on the French right, between the Saint-Charles River and Beauport.

This plan was put on hold on 20 July, when an event of great import to the British occurred: the Royal Navy succeeded, on the night of 18–19 July, in passing seven ships, including the ship of the line HMS Sutherland and two frigates (HMS Diana and HMS Squirrel), through the narrow passage between Quebec and Pointe-Lévy, thus opening the possibility of a landing west of Quebec.[5] Batteries firing at the British flotilla from the Lower Town of Quebec, as well as the floating batteries pursuing it, were unable to prevent the crossing. The Sutherland's log records that the French cannonballs flew too high to cause serious damage.[6]

On 19 July Wolfe was at the Pointe-Lévy camp to reconnoitre the north shore west of Quebec. He moved further west the next day, near the mouth of the Chaudière River, to study the opposite shore between Sillery and Cap Rouge.[6] Wolfe wrote to Monckton with orders for a plan of attack involving a landing near the village of Saint-Michel, something he had already considered in June.[7] However, at 13:00, Wolfe countermanded his orders to Monckton, ordering him instead to wait a few days and remain ready to act quickly, because of some "particular circumstances".[8] It is possible that the circumstance he alluded to was a French counteroffensive in which a newly built battery at Samos (near Sillery) damaged the Squirrel.

Wolfe returned to the Montmorency camp on 26 July. Escorted by two battalions, he walked up the Montmorency river to reconnoitre the French lines. At about five kilometres (3.1 mi) from the river's mouth, he observed a ford allowing the easy crossing from the west shore to the east shore. This discovery was followed by a solid skirmish between British soldiers, attempting to cross, and French soldiers entrenched on the other side. The British reported 45 killed and wounded.[9]

On 28 July, Wolfe wrote of an attack on the Beauport line to be executed on 30 July. However, poor winds did not allow for naval movements that day and the operations were postponed to the next day.[10] The plan of attack then contemplated by Wolfe was a variation of the plan he had described to Monckton in his letter of 16 July. Unlike the earlier plan, there was no mention of a parallel landing on the French right (west of Beauport).

Battle

Dangers of plan exposed

On the morning of 31 July the war vessel Centurion positioned itself by the Montmorency Falls to attack the easternmost French batteries. General Wolfe went on board the Russell, one of the two armed transports (the other being the Three Sisters) that were meant for the attack on the redoubt. Wolfe, who was then in the heat of the action, had a better chance to reconnoitre the French position than he could from Île d'Orléans. He immediately realized his mistake: the redoubt he hoped to seize to force the French out of their entrenchments was within range of enemy fire. The French soldiers could then very well shoot toward the redoubt without leaving their entrenchments on high ground. This fact changed everything and Wolfe's plan of attack consequently proved riskier than expected.[11]

In spite of this, General Wolfe decided to proceed with the attack already underway. In his journal, he stated that it was "the confusion and disorder" he observed on the enemy's side which incited him to action. Townshend, who commanded at Montmorency, and Monckton who was doing the same at Pointe-Lévy, received the order to prepare for the attack.

Difficult landing

At around 11:00, the transport ships (Russell and Three Sisters) reached the north shore where the body of troops mobilized to take the redoubt landed. Toward 12:30, the boats transporting the main landing force left the Île d'Orléans to rendezvous with Wolfe. An unforeseen difficulty caused the landing planned a little to the west of the Montmorency Falls to be suspended: the boats met with a shoal preventing them from reaching the shore. A significant amount of time was lost trying to find a suitable site for landing, which finally occurred at around 17:30.[12] By that time, the sky was covered by storm clouds.

Confrontation

The first troops advancing toward French lines were the thirteen companies of grenadiers and some 200 soldiers of the Royal Americans.[13] Fire from the Montreal militia stalled their advance up the hill to the entrenchments above.[14]

Shortly after the firing began, a summer storm broke out, causing gunpowder to become wet and rendering firearms unusable.[15] When General Wolfe ordered the retreat, the troops marching from the Montmorency camp had not yet met up with the main force transported from the Île d'Orléans camp.[13]

Consequences

The French were victorious. General Wolfe recorded 443 losses (210 killed and 233 wounded),[1] while the French counted 60 killed and wounded on their side; losses which were attributed to the fire coming from the great battery of the Montmorency camp.[2] The day after the battle, Wolfe wrote Monckton that the losses incurred in the battle were not great and that the defeat was no cause of discouragement.[16]

While the news of the victory was celebrated in the French camp, General Montcalm remained lucid, writing to Bourlamaque that in his opinion this attack was only a prelude to a more important one, which they could do nothing but patiently wait for.[14] The attack did eventually arrive, when on 13 September the British landed west of Quebec and defeated the French on the Plains of Abraham in a battle that claimed the lives of both Montcalm and Wolfe.

Notes

- 1 2 McLynn, Frank (2004). 1759: The Year Britain became Master of the World, p. 221

- 1 2 Stacey, pp. 79-80

- ↑ Stacey, p.60

- ↑ Stacey, p. 66

- ↑ Stacey, pp. 67-68

- 1 2 Stacey, p. 68

- ↑ Stacey, p. 69

- ↑ Stacey, p. 70

- ↑ Stacey, p. 72

- ↑ Stacey, p. 74

- ↑ Stacey, pp. 75-76

- ↑ Stacey, pp. 76-77

- 1 2 Stacey, p. 77

- 1 2 Stacey, p. 80

- ↑ Stacey, p. 78

- ↑ Stacey, p. 81

References

- Journal of the Expedition up the St. Lawrence

- McLynn, Frank (2004). 1759: The Year Britain became Master of the World, Jonathan Cape, London, ISBN 0-224-06245-X

- Stacey, Charles Perry (1959). Quebec, 1759: The Siege and The Battle, Toronto: MacMillan

- J.Bradley Cruxton, W. Douglas Wilson, Robert J. Walker (2001). "Close-Up Canada", Oxford, New York, ISBN 0-19-5415442

External links

- Invasion of the Beauport Shore (CBC)

- A Map of the Plan of the River St. Laurence with the Operations of the Siege of Quebec. On Sept. 5, 1759, in Archiving Early America