Battle of Yongsan

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

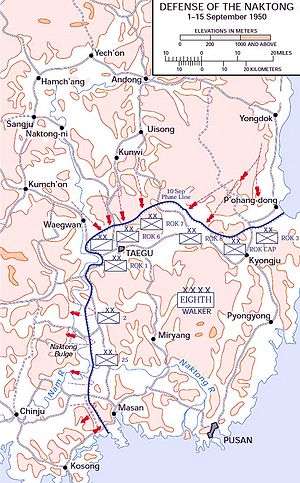

The Battle of Yongsan was an engagement between United Nations (UN) and North Korean (NK) forces early in the Korean War from September 1–5, 1950, at Yongsan in South Korea. It was part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter and was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously. The battle ended in a victory for the United Nations after large numbers of United States (US) and South Korean troops repelled a strong North Korean attack.

During the nearby Second Battle of Naktong Bulge, the North Korean People's Army broke through the US Army's 2nd Infantry Division lines along the Naktong River. Exploiting this weakness, the NK 9th Division and NK 4th Division attacked to Yongsan, a village east of the river and the gateway to the UN lines of supply and reinforcement for the Pusan Perimeter. What followed was a fight between North Korean and US forces for Yongsan.

The North Koreans were able to briefly capture Yongsan from the 2nd Infantry Division, which had been split in half from the penetrations at Naktong Bulge. Lieutenant General Walton Walker, seeing the danger of the attack, brought in the US Marine Corps 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to counterattack. In three days of fierce fighting, the Army and Marine forces were able to push the North Koreans out of the town and destroy the two attacking divisions. The win was a key step toward victory in the fight at the Naktong Bulge.

Background

Pusan Perimeter

From the outbreak of the Korean War and the invasion of South Korea by the North, the North Korean People's Army had enjoyed superiority in both manpower and equipment over both the Republic of Korea Army and the United Nations forces dispatched to South Korea to prevent it from collapsing.[1] The North Korean strategy was to aggressively pursue UN and ROK forces on all avenues of approach south and to engage them aggressively, attacking from the front and initiating a double envelopment of both flanks of the unit, which allowed the North Koreans to surround and cut off the opposing force, which would then be forced to retreat in disarray, often leaving behind much of its equipment.[2] From their initial June 25 offensive to fights in July and early August, the North Koreans used this strategy to effectively defeat any UN force and push it south.[3] However, when the UN forces, under the Eighth United States Army, established the Pusan Perimeter in August, the UN troops held a continuous line along the peninsula which North Korean troops could not flank, and their advantages in numbers decreased daily as the superior UN logistical system brought in more troops and supplies to the UN army.[4]

When the North Koreans approached the Pusan Perimeter on August 5, they attempted the same frontal assault technique on the four main avenues of approach into the perimeter. Throughout August, the NK 6th Division, and later the NK 7th Division, engaged the US 25th Infantry Division at the Battle of Masan, initially repelling a UN counteroffensive before countering with battles at Komam-ni[5] and Battle Mountain.[6] These attacks stalled as UN forces, well equipped and with plenty of reserves, repeatedly repelled North Korean attacks.[7] North of Masan, the NK 4th Division and the US 24th Infantry Division sparred in the Naktong Bulge area. In the First Battle of Naktong Bulge, the North Korean division was unable to hold its bridgehead across the river as large numbers of US reserve forces were brought in to repel it, and on August 19, the NK 4th Division was forced back across the river with 50 percent casualties.[8][9] In the Taegu region, five North Korean divisions were repulsed by three UN divisions in several attempts to attack the city during the Battle of Taegu.[10][11] Particularly heavy fighting took place at the Battle of the Bowling Alley where the NK 13th Division was almost completely destroyed in the attack.[12] On the east coast, three more North Korean divisions were repulsed by the South Koreans at P'ohang-dong during the Battle of P'ohang-dong.[13] All along the front, the North Korean troops were reeling from these defeats, the first time in the war their strategies were not working.[14]

September push

In planning its new offensive, the North Korean command decided any attempt to flank the UN force was impossible thanks to the support of the UN navy.[12] Instead, they opted to use frontal attack to breach the perimeter and collapse it; this was considered to be the only hope of achieving success in the battle.[4] Fed by intelligence from the Soviet Union, the North Koreans were aware of the UN forces building up along the Pusan Perimeter and that they must conduct an offensive soon or they could not win the battle.[15] A secondary objective was to surround Taegu and destroy the UN and ROK units in that city. As part of this mission, the North Korean units would first cut the supply lines to Taegu.[16][17]

On August 20, the North Korean commands distributed operations orders to their subordinate units.[15] The North Koreans called for a simultaneous five-prong attack against the UN lines. These attacks would overwhelm the UN defenders and allow the North Koreans to break through the lines in at least one place to force the UN forces back. Five battle groupings were ordered.[18] The center attack called for the NK 9th Division, NK 4th Division, NK 2nd Division, and NK 10th Division break through the US 2nd Infantry Division at the Naktong Bulge to Miryang and Yongsan.[19]

Battle

On the morning of September 1 the 1st and 2nd Regiments of the NK 9th Division, in their first offensive of the war, stood only a few miles short of Yongsan after a successful river crossing and penetration of the American line.[20][21] The 3rd Regiment had been left at Inch'on, but division commander Major General Pak Kyo Sam felt the chances of capturing Yongsan were strong.[22]

As the NK 9th Division approached Yongsan, its 1st Regiment was on the north and its 2nd Regiment on the south.[20] The division's attached support, consisting of one 76 mm artillery battalion from the NK I Corps, an antiaircraft battalion of artillery, two tank battalions of the NK 16th Armored Brigade, and a battalion of artillery from the NK 4th Division, gave it unusually heavy support.[23][24] Crossing the river behind it came the 4th Division, a greatly weakened organization, far understrength, short of weapons, and made up mostly of untrained replacements.[20] A captured North Korean document referred to this grouping of units that attacked from the Sinban-ni area into the Naktong Bulge as the main force of NK I Corps. Elements of the 9th Division reached the hills just west of Yongsan during the afternoon of September 1.[23][25]

On the morning of September 1, with only the shattered remnants of E Company at hand, the US 9th Infantry Regiment, US 2nd Infantry Division had virtually no troops to defend Yongsan.[20] Division commander Major General Laurence B. Keiser in this emergency attached the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion to the regiment. The US 72nd Tank Battalion and the 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company also were assigned positions close to Yongsan. The regimental commander planned to place the engineers on the chain of low hills that arched around Yongsan on the northwest.[23]

North Korean attack

A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, moved to the south side of the Yongsan-Naktong River road; D Company of the 2nd Engineer Battalion was on the north side of the road. Approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan an estimated 300 North Korean troops engaged A Company in a fire fight.[26] M19 Gun Motor Carriages of the 82nd AAA Battalion supported the engineers in this action, which lasted several hours.[23] Meanwhile, with the approval of General Bradley, D Company moved to the hill immediately south of and overlooking Yongsan.[23] A platoon of infantry went into position behind it. A Company was now ordered to fall back to the southeast edge of Yongsan on the left flank of D Company. There, A Company went into position along the road; on its left was C Company of the Engineer battalion, and beyond C Company was the 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company. The hill occupied by D Company was in reality the western tip of a large mountain mass that lay southeast of the town.[23] The road to Miryang came south out of Yongsan, bent around the western tip of this mountain, and then ran eastward along its southern base.[20] In its position, D Company not only commanded the town but also its exit, the road to Miryang.[23][27]

North Koreans had also approached Yongsan from the south.[28] The US 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company and tanks of the 72nd Tank Battalion opposed them in an intense fight.[23] In this action, Sergeant First Class Charles W. Turner of the Reconnaissance Company particularly distinguished himself. He mounted a tank, operated its exposed turret machine gun, and directed tank fire which reportedly destroyed seven North Korean machine guns. Turner and this tank came under heavy North Korean fire which shot away the tank's periscope and antennae and scored more than 50 hits on it. Turner, although wounded, remained on the tank until he was killed. That night North Korean soldiers crossed the low ground around Yongsan and entered the town from the south.[29][30]

The North Koreans now attempted a breakthrough of the Engineer position.[28] After daylight, they were unable to get reinforcements into the fight since D Company commanded the town and its approaches. In this fight, which raged until 11:00, the engineers had neither artillery nor mortar support. D Company remedied this by using its new 3.5-inch and old 2.36-inch rocket launchers against the North Korean infantry.[29] The fire of the 18 bazookas plus that from machine guns and the small arms of the company inflicted very heavy casualties on the North Koreans, who desperately tried to clear the way for a push eastward to Miryang.[28] Tanks of A and B Companies, 72nd Tank Battalion, at the southern and eastern edge of Yongsan shared equally with the engineers in the intensity of this battle.[26] The company commander was the only officer of D Company not killed or wounded in this melee, which cost the company 12 men killed and 18 wounded. The edge of Yongsan and the slopes of the hill south of the town became covered with North Korean dead and destroyed equipment.[29]

Reinforcements

While this battle raged during the morning at Yongsan, commanders reorganized about 800 men of the 9th Infantry who had arrived in that vicinity from the overrun river line positions.[30] Among them were F and G Companies, which were not in the path of major North Korean crossings and had succeeded in withdrawing eastward.[31] They had no crew-served weapons or heavy equipment.[32] In midafternoon September 2, tanks and the reorganized US 2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry, attacked through A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, into Yongsan, and regained possession of the town at 15:00.[33] Later, two bazooka teams from A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, knocked out three T-34 tanks just west of Yongsan. American ground and air action destroyed other North Korean tanks during the day southwest of the town.[29] By evening the North Koreans had been driven into the hills westward.[26] In the evening, the 2nd Battalion and A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, occupied the first chain of low hills 0.5 miles (0.80 km) beyond Yongsan, the engineers west and the 2nd Battalion northwest of the town.[31] For the time being at least, the North Korean drive toward Miryang had been halted.[32] In this time, the desperately undermanned US units began to be reinforced with Korean Augmentees (KATUSAs.) However, the cultural divide between the KATUSAs and the US troops caused tensions.[34]

At 09:35 September 2, while the North Koreans were attempting to destroy the engineer troops at the southern edge of Yongsan and clear the road to Miryang,[33] Eighth United States Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker spoke by telephone with Major General Doyle O. Hickey, Deputy Chief of Staff, Far East Command in Tokyo.[32] He described the situation around the Perimeter and said the most serious threat was along the boundary between the US 2nd and US 25th Infantry Divisions.[31] He described the location of his reserve forces and his plans for using them. He said he had started the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, under Brigadier General Edward A. Craig, toward Yongsan but had not yet released them for commitment there and he wanted to be sure that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur approved his use of them, since he knew that this would interfere with other plans of the Far East Command.[35] Walker said he did not think he could restore the 2nd Division lines without using them. Hickey replied that MacArthur had the day before approved the use of the US Marines if and when Walker considered it necessary.[32] A few hours after this conversation, at 13:15, Walker attached the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to the US 2nd Division[36] and ordered a co-ordinated attack by all available elements of the division and the marines, with the mission of destroying the North Koreans east of the Naktong River in the 2nd Division sector and restoring the river line.[31][33] The marines were to be released from 2nd Division control as soon as this mission was accomplished.[32][37]

September 3 counterattack

A conference was held that afternoon at the US 2nd Division command post attended by leaders of the Eighth Army, US 2nd Division, and 1st Marine Brigade.[38] A decision was reached that the marines would attack west at 08:00 on September 3 astride the Yongsan-Naktong River road;[39] the 9th Infantry, B Company of the 72nd Tank Battalion, and D Battery of the 82d AAA Battalion would attack northwest above the marines and attempt to re-establish contact with the US 23rd Infantry;[38] the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, remnants of the 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry, and elements of the 72nd Tank Battalion would attack on the left flank, or south, of the marines to reestablish contact with the 25th Division.[40] Eighth Army now ordered the US 24th Infantry Division headquarters and the US 19th Infantry Regiment to move to the Susan-ni area, 8 miles (13 km) south of Miryang and 15 miles (24 km) east of the confluence of the Nam River and the Naktong River. There it was to prepare to enter the battle in either the 2nd or 25th Division zone.[32]

The troops holding this line on the first hills west of Yongsan were G Company, 9th Infantry, north of the road running west through Kogan-ni to the Naktong; A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, southward across the road; and, below the engineers, F Company, 9th Infantry.[41] Between 03:00 and 04:30 September 3, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade moved to forward assembly areas.[39] The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines assembled north of Yongsan, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines south of it. The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines established security positions southwest of Yongsan along the approaches into the regimental sector from that direction.[38][41]

During the night, A Company of the engineers had considerable fighting with North Koreans and never reached its objective.[40] At dawn September 3, A Company attacked to gain the high ground which was part of the designated Marine line of departure.[39] The company fought its way up the slope to within 100 yards (91 m) of the top, which was held by the firmly entrenched North Koreans.[41] At this point the company commander caught a North Korean-thrown grenade and was wounded by its fragments as he tried to throw it away from his men. The company with help from Marine tank fire eventually gained its objective, but this early morning battle for the line of departure delayed the planned attack.[42]

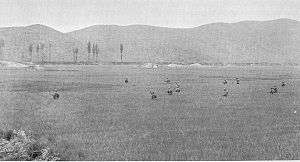

The Marine attack started at 08:55 across the rice paddy land toward North Korean-held high ground 0.5 miles (0.80 km) westward.[40] The 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, south of the east-west road, gained its objective when North Korean soldiers broke under air attack and ran down the northern slope and crossed the road to Hill 116 in the 2nd Battalion zone.[39] Air strikes, artillery concentrations, and machine gun and rifle fire of the 1st Battalion now caught North Korean reinforcements in open rice paddies moving up from the second ridge and killed most of them. In the afternoon, the 1st Battalion advanced to Hill 91.[42]

North of the road the 2nd Battalion had a harder time, encountering heavy North Korean fire when it reached the northern tip of Hill 116, 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan.[39] The North Koreans held the hill during the day, and at night D Company of the 5th Marines was isolated there.[42] In the fighting west of Yongsan Marine armor knocked out four T-34 tanks, and North Korean crew members abandoned a fifth.[40] That night the marines dug in on a line 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan. The 2nd Battalion had lost 18 killed and 77 wounded during the day, most of them in D Company. Total Marine casualties for September 3 were 34 killed and 157 wounded. Coordinating its attack with that of the marines, the 9th Infantry advanced abreast of them on the north.[42]

September 4 counterattack

Just before midnight, the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, received orders to pass through the 2nd Battalion and continue the attack in the morning.[39] That night torrential rains made the troops miserable and lowered morale. The North Koreans were unusually quiet and launched few patrols or attacks. The morning of September 4, the weather was clear.[42][43]

The counterattack continued at 08:00 September 4, at first against little opposition.[44] North of the road the 2nd Battalion quickly completed occupation of Hill 116, from which the North Koreans had withdrawn during the night. South of the road the 1st Battalion occupied what appeared to be a command post of the NK 9th Division. Tents were still up and equipment lay scattered about. Two abandoned T-34 tanks in excellent condition stood there. Tanks and ground troops advancing along the road found it littered with North Korean dead and destroyed and abandoned equipment. By nightfall the counterattack had gained another 3 miles (4.8 km).[42]

That night was quiet until just before dawn. The North Koreans then launched an attack against the 9th Infantry on the right of the marines, the heaviest blow striking G Company.[43] It had begun to rain again and the attack came in the midst of a downpour.[39][45] In bringing his platoon from an outpost position to the relief of the company, Sergeant First Class Loren R. Kaufman encountered an encircling North Korean force on the ridge line.[42] He bayoneted the lead scout and engaged those following with grenades and rifle fire. His sudden attack confused and dispersed this group. Kaufman led his platoon on and succeeded in joining hard-pressed G Company.[46] In the ensuing action Kaufman led assaults against close-up North Korean positions and, in hand-to-hand fighting, he bayoneted four more North Korean soldiers, destroyed a machine gun position, and killed the crew members of a North Korean mortar. American artillery fire concentrated in front of the 9th Infantry helped greatly in repelling the North Koreans in this night and day battle.[47]

September 5 counterattack

That morning, September 5, after a 10-minute artillery preparation, the American troops moved out in their third day of counterattack.[48] It was a day of rain. As the attack progressed, the marines approached Obong-ni Ridge and the 9th Infantry neared Cloverleaf Hill where they had fought tenaciously during the First Battle of Naktong Bulge the month before.[39] There, at midmorning, on the high ground ahead, they could see North Korean troops digging in. The marines approached the pass between the two hills and took positions in front of the North Korean-held high ground.[47]

At 14:30 approximately 300 North Korean infantry came from the village of Tugok and concealed positions, striking B Company on Hill 125 just north of the road and east of Tugok.[39] Two T-34 tanks surprised and knocked out the two leading Marine M26 Pershing tanks. Since the destroyed Pershing tanks blocked fields of fire, four others withdrew to better positions.[47] Assault teams of B Company and the 1st Battalion with 3.5-inch rocket launchers rushed into action, took the tanks under fire, and destroyed both of them, as well as an armored personnel carrier following behind.[39] The North Korean infantry attack was brutal and inflicted 25 casualties on B Company before reinforcements from A Company and supporting Army artillery and the Marine 81 mm mortars helped repel it.[47][49]

September 5 was a day of heavy casualties everywhere on the Pusan Perimeter.[50] Army units had 102 killed, 430 wounded, and 587 missing in action for a total of 1,119 casualties. Marine units had 35 killed, 91 wounded, and none missing in action, for a total of 126 battle casualties. Total American battle casualties for the day were 1,245 men.[47] It is unknown how many North Koreans were killed or wounded on that day, but they likely suffered heavy casualties.[51]

North Koreans repulsed

During the previous night, at 20:00 September 4, General Walker had ordered the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade released from operational control of the 2nd Division effective at midnight, September 5.[50] He had vainly protested against releasing the brigade, believing he needed it and all the troops then in Korea if he were to stop the North Korean offensive against the Pusan Perimeter. At 00:15, September 6, the marines began leaving their lines at Obong-ni Ridge and headed for Pusan. They would join the 1st Marine Regiment and 7th Marine Regiment in forming the new 1st Marine Division.[47]

The American counteroffensive of September 3–5 west of Yongsan, according to prisoner statements, resulted in one of the bloodiest debacles of the war for a North Korean division. Even though remnants of the NK 9th Division, supported by the low strength NK 4th Division, still held Obong-ni Ridge, Cloverleaf Hill, and the intervening ground back to the Naktong on September 6, the division's offensive strength had been spent at the end of the American counterattack.[50] The NK 9th and 4th divisions were not able to resume the offensive.[52]

Just after midnight on September 6, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was ordered back to Pusan in order to travel to Japan and merge with other Marine units to form the 1st Marine Division.[50] This was done after a heated disagreement between Walker's command and MacArthur's command. Walker said he could not hold the Pusan Perimeter without the Marines in reserve, while MacArthur said he could not conduct the Inchon landings without the Marines.[49] MacArthur responded by assigning the 17th Infantry Regiment, and later the 65th Infantry Regiment, would be added to Walker's reserves, but Walker did not feel the inexperienced troops would be effective. Walker felt the transition endangered the Perimeter at a time when it was unclear if it would hold.[53][54]

Aftermath

The North Korean 4th and 9th Divisions were almost completely destroyed in the battles at Naktong Bulge. The 9th Division had numbered 9,350 men at the beginning of the offensive on September 1. The 4th Division numbered 5,500.[18] Only a few hundred from each division returned to North Korea after the Second Battle of Naktong Bulge. The majority of the North Korean troops had been killed, captured or deserted. The exact number of North Korean casualties at Yongsan is impossible to determine, but a substantial amount of the attacking force was lost there.[51] All of NK II Corps was in a similar state, and the North Korean army, exhausted at Pusan Perimeter and cut off after Inchon, was on the brink of defeat.[55]

The US casualty count at Yongsan is also difficult to know, as the division's scattered units were engaged all along the Naktong Bulge without communication and total casualty counts in each area could not be ascertained. The US 2nd Infantry Division suffered 1,120 killed, 2,563 wounded, 67 captured and 69 missing during its time at the Second Battle of Naktong Bulge.[56] This included about 180 casualties it suffered during the First Battle of Naktong Bulge the previous month.[57] American forces were continually repulsed but able to prevent the North Koreans from breaking the Pusan Perimeter.[58] The division had numbered 17,498 on September 1, but was in excellent position to attack despite its casualties.[59] The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade suffered 185 killed and around 500 wounded during the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, most of which probably occurred at Yongsan.[60]

Once again the fatal weakness of the North Korean Army had cost it victory after an impressive initial success-its communications and supply were not capable of exploiting a breakthrough and of supporting a continuing attack in the face of massive air, armor, and artillery fire that could be concentrated against its troops at critical points.[52][48] By September 8, the North Korean attacks in the area had been repulsed.[35]

References

Citations

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 392

- ↑ Varhola 2004, p. 6

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 138

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 393

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 367

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 149

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 369

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 130

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 139

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 353

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 143

- 1 2 Catchpole 2001, p. 31

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 139

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 508

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 181

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 395

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 396

- 1 2 3 4 5 Millett 2000, p. 532

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 33

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 459

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Appleman 1998, p. 460

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 34

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 182

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 148

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 146

- 1 2 3 Millett 2000, p. 533

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 461

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 183

- 1 2 3 4 Millett 2000, p. 534

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 462

- 1 2 3 Alexander 2003, p. 184

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 149

- 1 2 Catchpole 2001, p. 36

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 147

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 35

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 150

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alexander 2003, p. 185

- 1 2 3 4 Millett 2000, p. 535

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 463

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Appleman 1998, p. 464

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 151

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 536

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 152

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 153

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 465

- 1 2 Millett 2000, p. 537

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 186

- 1 2 3 4 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 154

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 603

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 464

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 187

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 158

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 604

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 16

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 20

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 14

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 382

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 20

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0

- Bowers, William T.; Hammong, William M.; MacGarrigle, George L. (2005), Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2467-5

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books Inc., ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

- Millett, Allan R. (2000), The Korean War, Volume 1, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7794-6

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4