Bigraph

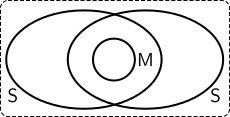

A bigraph (often used in the plural bigraphs) can be modelled as the superposition of a graph (the link graph) and a set of trees (the place graph).[1][2]

Each node of the bigraph is part of a graph and also part of some tree that describes how the nodes are nested. Bigraphs can be conveniently and formally displayed as diagrams.[1] They have applications in the modelling of distributed systems for ubiquitous computing and can be used to describe mobile interactions. They have also been used by Robin Milner in an attempt to subsume Calculus of Communicating Systems (CCS) and π-calculus.[2] They have been studied in the context of category theory.[3]

Anatomy of a bigraph

Aside from nodes and (hyper-)edges, a bigraph may have associated with it one or more regions which are roots in the place forest, and zero or more holes in the place graph, into which other bigraph regions may be inserted. Similarly, to nodes we may assign controls that define identities and an arity (the number of ports for a given node to which link-graph edges may connect). These controls are drawn from a bigraph signature. In the link graph we define inner and outer names, which define the connection points at which coincident names may be fused to form a single link.

Foundations

A bigraph is a 5-tuple:

where is a set of nodes, is a set of edges, is the control map that assigns controls to nodes, is the parent map that defines the nesting of nodes, and is the link map that defines the link structure.

The notation indicates that the bigraph has holes (sites) and a set of inner names and regions, with a set of outer names . These are respectively known as the inner and outer interfaces of the bigraph.

Formally speaking, each bigraph is an arrow in a symmetric partial monoidal category (usually abbreviated spm-category) in which the objects are these interfaces.[4] As a result, the composition of bigraphs is definable in terms of the composition of arrows in the category.

Extensions and variants

Bigraphs with sharing

Bigraphs with sharing[5] are a generalisation of Milner's formalisation that allows for a straightforward representation of overlapping or intersecting spatial locations. In bigraphs with sharing, the place graph is defined as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), i.e. is a binary relation instead of a map. The definition of link graph is unaffected by the introduction of sharing. Note that standard bigraphs are a sub-class of bigraphs with sharing.

Areas of application of bigraphs with sharing include wireless networking protocols[6] and real-time management of domestic wireless networks.[7]

See also

Bibliography

- Milner, Robin (2009). The Space and Motion of Communicating Agents. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521738334.

- Milner, Robin (2001). "Bigraphical reactive systems, (invited paper)". CONCUR 2001 – Concurrency Theory, Proc. 12th International Conference. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2154. Springer-Verlag. pp. 16–35. doi:10.1007/3-540-44685-0_2.

- Milner, Robin (2002). "Bigraphs as a Model for Mobile Interaction (invited paper)". ICGT 2002: First International Conference on Graph Transformation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2505. Springer-Verlag. pp. 8–13. doi:10.1007/3-540-45832-8_3.

- Debois, Søren; Damgaard, Troels Christoffer (2005). "Bigraphs by Example". IT University Technical Report Series TR-2005-61. Denmark: IT University of Copenhagen. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.73.176

. ISBN 87-7949-090-5.

. ISBN 87-7949-090-5. - Sevegnani, Michele; Calder, Muffy (2015). "Bigraphs with sharing". Theoretical Computer Science. Elsevier. 577: 43–73. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2015.02.011.

References

- 1 2 A Brief Introduction To Bigraphs, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 1 2 Milner, Robin. The Bigraphical Model, University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory, UK.

- ↑ Milner, Robin (2008). "Bigraphs and Their Algebra". Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science. 209: 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.entcs.2008.04.002.

- ↑ Milner, Robin (2009). "Bigraphical Categories". CONCUR 2009 - Concurrency Theory. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 5710. Springer-Verlag. pp. 30–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04081-8_3.

- ↑ Sevegnani, Michele; Calder, Muffy (2015). "Bigraphs with sharing". Theoretical Computer Science. Elsevier. 577: 43–73. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2015.02.011.

- ↑ Calder, Muffy; Sevegnani, Michele (2014). "Modelling IEEE 802.11 CSMA/CA RTS/CTS with stochastic bigraphs with sharing". Formal Aspects of Computing. Springer London. 26: 537–561. doi:10.1007/s00165-012-0270-3.

- ↑ Calder, Muffy; Koliousis, Alexandros; Sevegnani, Michele; Sventek, Joseph (2014). "Real-time verification of wireless home networks using bigraphs with sharing". Science of Computer Programming. Elsevier. 80: 288–310. doi:10.1016/j.scico.2013.08.004.