Black Square (painting)

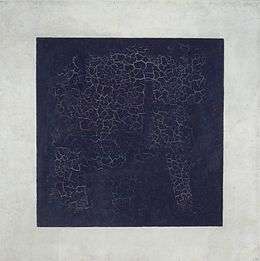

The Black Square, Black Square or Malevich's Black Square is an iconic painting by Kazimir Malevich. The first version was done in 1915. Malevich made four variants of which the last is thought to have been painted during the late 1920s or early 1930s. The Black Square was first shown in The Last Futurist Exhibition 0.10 in 1915. The work is frequently invoked by critics, historians, curators, and artists as the “zero point of painting", referring to the painting's historical significance and paraphrasing Malevich.

History

Malevich painted his first Black Square in 1915.[2] He made four variants of which the last is thought to have been painted during the late 1920s or early 1930s, despite the author's "1913" inscription on the reverse.[3][4][5] The painting is commonly known as Black Square, The Black Square or as Malevich's Black Square. It was first shown in The Last Futurist Exhibition 0.10 in 1915.

Forensic detail reveals of how Black Square was painted over a more complex and colorful composition.[4]

Historical context

A plurality of art historians, curators, and critics refer to Black Square as one of the seminal works of modern art, and of abstract art in the Western painterly tradition generally.

Malevich declared the square a work of Suprematism, a movement which he proclaimed but which is associated almost exclusively with the work Malevich and his apprentice Lissitzky today. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. Suprematism may be understood as a transitional phase in the evolution of Russian art, bridging the evolutionary gap between futurism and constructivism.

The larger and more universal leap forward represented by the painting, however, is the break between representational painting and abstract painting—a complex transition with which Black Square has become identified and for which it has become one of the key shorthands, touchstones or symbols.[6]

Perception

The work is frequently invoked by critics, historians, curators, and artists as the “zero point of painting",[7][8][9] referring to the painting's historical significance as a paraphrase of a number of comments Malevich made about The Black Square in letters to his colleagues and dealers.

Malevich had made some remarks about his painting.

- “It is from zero, in zero, that the true movement of being begins.”[10]

- "I transformed myself in the zero of form and emerged from nothing to creation, that is, to Suprematism, to the new realism in painting - to non-objective creation."[10]

- "[Black Square is meant to evoke] the experience of pure non-objectivity in the white emptiness of a liberated nothing."[10]

Peter Schjeldahl wrote:[8]

"The brushwork is juicy and brusque: filling in the shapes, fussing with the edges. But the forms are weightless, more like thoughts than like images. You don’t look at the picture so much as launch yourself into its trackless empyrean. Beyond its obvious design flair, the work looks easy because it is. Malevich is monumental not for what he put into pictorial space but for what he took out: bodily experience, the fundamental theme of Western art since the Renaissance. His appeal to Americans isn’t surprising. Apart from a peculiarly Russian mystical tradition, which he exploited—evoking the compact spell of the icon, as a conduit of the divine—his work amounts to a cosmic “Song of the Open Road.” It conveys sheer, surging, untrammelled possibility. This quality seemed in synch with the Revolution of 1917. It wasn’t—which Malevich was painfully made aware of, first by his rivals in the Russian avant-garde and then, conclusively, by the regime of Joseph Stalin."

Conservation

Negligence and contempt on the part of the Soviet government in whose keeping the original Black Square remained for decades has resulted in the painting degrading considerably.[11]

Peter Schjeldahl writes:[8]

"The painting looks terrible: crackled, scuffed, and discolored, as if it had spent the past eighty-eight years patching a broken window. In fact, it passed most of that time deep in the Soviet archives, classed among the lowliest of the state's treasures. Malevich, like other members of the Revolutionary-era Russian avant-garde, was thrown into oblivion under Stalin. The axe fell on him in 1930. Accused of "formalism", he was interrogated and jailed for two months."

See also

References

- ↑ "Malevich, Black Square, 1915, Guggenheim New York, exhibition, 2003-2004". Archive.org. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ John Milner, Suprematism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ Kasimir Malevich. Black Square, Hermitage Museum

- 1 2 Kudriavtseva, Catherine I. "The Making of Kazimir Malevich's Black Square". University of Southern California. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Meinhardt, Johannes. "The Painting As Empty Space". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Collings, Matthew. "The Rules of Abstraction". BBC.

- ↑ Mazzoni, Ira. "Everything and Nearly Nothing: Malevich and His Effects". DeutscheBank/Art. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Schjehldahl, Peter. "The Prophet: Malevich's Revolution". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Schjehldahl, Peter. "The Shape of Things:After Kazimir Malevich". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Malevich, K. "Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism". Guggenheim. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Philip Shaw. The Art of the Sublime – 'Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square'. Tate Research Publication, January 2013. Retrieved 06 July 2016.