Borneo

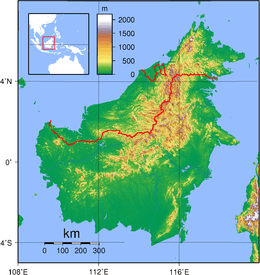

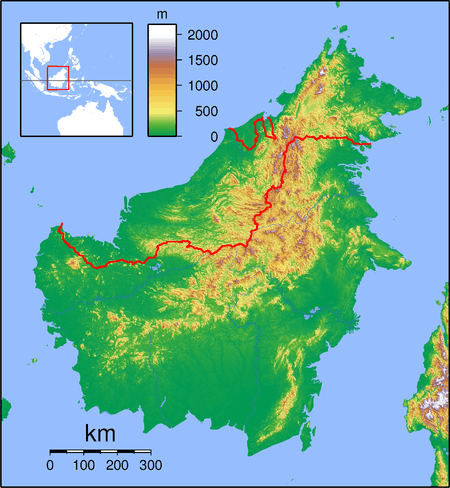

Topography of Borneo | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Southeast Asia |

| Coordinates | 01°N 114°E / 1°N 114°ECoordinates: 01°N 114°E / 1°N 114°E |

| Archipelago | Greater Sunda Islands |

| Area | 743,330 km2 (287,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 3rd |

| Highest elevation | 4,095 m (13,435 ft) |

| Highest point | Kinabalu |

| Administration | |

| Districts |

Belait Brunei and Muara Temburong Tutong |

| Provinces |

West Kalimantan Central Kalimantan South Kalimantan East Kalimantan North Kalimantan |

| States and FT |

Sabah Sarawak Labuan |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 19,804,064 (2010) |

| Pop. density | 21.52 /km2 (55.74 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Dayak, Iban, Kadazan-Dusun, Banjar, Sama-Bajau, Murut, Rungus and Bruneian Malay |

Borneo (/ˈbɔːrnioʊ/; Indonesian: Kalimantan, Malay: Borneo) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest island in Asia.[1] At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and east of Sumatra.

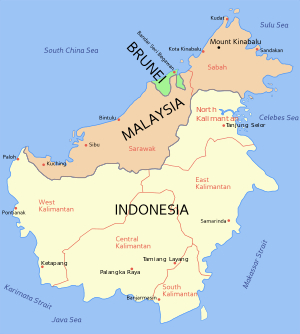

The island is politically divided among three countries: Malaysia and Brunei in the north, and Indonesia to the south. Approximately 73% of the island is Indonesian territory. In the north, the East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak make up about 26% of the island. Additionally, the Malaysian federal territory of Labuan is situated on a small island just off the coast of Borneo. The sovereign state of Brunei, located on the north coast, comprises about 1% of Borneo's land area. Antipodal to an area of Amazon rainforest, Borneo is itself home to one of the oldest rainforests in the world, and to Bornean orangutans.

Etymology

The island is known by many names; internationally it is known as Borneo, after Brunei, derived from European historical contact with the kingdom in the 16th century during the Age of Exploration. The name Brunei possibly was initially derived from the Sanskrit word "váruṇa" (वरुण), meaning either "ocean" or the mythological Varuna, the Hindu god of the ocean. Indonesian natives called it Kalimantan, which was derived from the Sanskrit word Kalamanthana, meaning "burning weather island" (to describe its hot and humid tropical weather).[2]

Prior to that the island was also known by other names. In 977 Chinese records began to use the term Po-ni to refer to Borneo. In 1225 it was also mentioned by the Chinese official Chau Ju-Kua (趙汝适).[3] The Javanese manuscript Nagarakretagama, written by Majapahit court poet Mpu Prapanca in 1365, mentioned the island as Nusa Tanjungnagara, which means the island of the Tanjungpura Kingdom.[4]

Geography

Borneo is surrounded by the South China Sea to the north and northwest, the Sulu Sea to the northeast, the Celebes Sea and the Makassar Strait to the east, and the Java Sea and Karimata Strait to the south. To the west of Borneo are the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra. To the south and east are islands of Indonesia: Java and Sulawesi, respectively. To the northeast are the Philippine Islands.

With an area of 743,330 square kilometres (287,000 sq mi), it is the third-largest island in the world, and is the largest island of Asia (the largest continent). Its highest point is Mount Kinabalu in Sabah, Malaysia, with an elevation of 4,095 m (13,435 ft).[5]

The largest river system is the Kapuas in West Kalimantan, with a length of 1,143 km (710 mi). Other major rivers include the Mahakam in East Kalimantan (980 km long (610 mi)), the Barito in South Kalimantan (880 km long (550 mi)), and Rajang in Sarawak (562.5 km long (349.5 mi)).

Borneo has significant cave systems. Clearwater Cave, for example, has one of the world's longest underground rivers. Deer Cave is home to over three million bats, with guano accumulated to over 100 metres (330 ft) deep.[6]

Before sea levels rose at the end of the last Ice Age, Borneo was part of the mainland of Asia, forming, with Java and Sumatra, the upland regions of a peninsula that extended east from present day Indochina. The South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand now submerge the former low-lying areas of the peninsula. Deeper waters separating Borneo from neighbouring Sulawesi prevented a land connection to that island, creating the divide known as Wallace's Line between Asian and Australia-New Guinea biological regions.

Ecology

The Borneo rainforest is 140 million years old, making it one of the oldest rainforests in the world. There are about 15,000 species of flowering plants with 3,000 species of trees (267 species are dipterocarps), 221 species of terrestrial mammals and 420 species of resident birds in Borneo.[7] There are about 440 freshwater fish species in Borneo (about the same as Sumatra and Java combined).[8] It is the centre of the evolution and distribution of many endemic species of plants and animals. The Borneo rainforest is one of the few remaining natural habitats for the endangered Bornean orangutan. It is an important refuge for many endemic forest species, including the Borneo elephant, the eastern Sumatran rhinoceros, the Bornean clouded leopard, the Hose's palm civet and the dayak fruit bat.

In 2010 the World Wide Fund for Nature stated that 123 species have been discovered in Borneo since the "Heart of Borneo" agreement was signed in 2007.[9]

The WWFN has classified the island into seven distinct ecoregions. Most are lowland regions:

- Borneo lowland rain forests cover most of the island, with an area of 427,500 square kilometres (165,100 sq mi);

- Borneo peat swamp forests;

- Kerangas or Sundaland heath forests;

- Southwest Borneo freshwater swamp forests; and

- Sunda Shelf mangroves.

- The Borneo montane rain forests lie in the central highlands of the island, above the 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) elevation. The highest elevations of Mount Kinabalu are home to the Kinabalu mountain alpine meadow, an alpine shrubland notable for its numerous endemic species, including many orchids.

The island historically had extensive rainforest cover, but the area was reduced due to heavy logging for the Malaysian and Indonesian plywood industry. Half of the annual global tropical timber acquisition comes from Borneo. Palm oil plantations have been widely developed and are rapidly encroaching on the last remnants of primary rainforest. Forest fires of 1997 to 1998, started by the locals to clear the forests for plantations were exacerbated by an exceptionally dry El Niño season, worsening the annual shrinkage of the rainforest. During these fires, hotspots were visible on satellite images and the resulting haze affected four countries: Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore.

In 2010 Sarawak announced a plan for energy production, the Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy, to try to establish sustainability.[10]

History

Early history

According to ancient Chinese (977),[11]:129 Indian and Javanese manuscripts, western coastal cities of Borneo had become trading ports by the first millennium.[12] In Chinese manuscripts, gold, camphor, tortoise shells, hornbill ivory, rhinoceros horn, crane crest, beeswax, lakawood (a scented heartwood and root wood of a thick liana, Dalbergia parviflora), dragon's blood, rattan, edible bird's nests and various spices were described as among the most valuable items from Borneo.[13] The Indians named Borneo Suvarnabhumi (the land of gold) and also Karpuradvipa (Camphor Island). The Javanese named Borneo Puradvipa, or Diamond Island. Archaeological findings in the Sarawak river delta reveal that the area was a thriving trading centre between India and China from the 6th century until about 1300.[13]

One of the earliest evidence of Hindu influence in Southeast Asia were stone pillars which bear inscriptions in the Pallava script, found in Kutai along the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan, dating to around the second half of the 4th century.[14] By the 14th century, Borneo became a vassal state of Majapahit based in present-day Indonesia.[15] Muslims entered the island and converted many of the indigenous peoples to Islam.

During the 1450s, Shari'ful Hashem Syed Abu Bakr, an Arab born in Johor, arrived in Sulu from Malacca. In 1457, he founded the Sultanate of Sulu; he titled himself as "Paduka Maulana Mahasari Sharif Sultan Hashem Abu Bakr". The Sultanate of Brunei, during its golden age from the 15th century to the 17th century, ruled a large part of northern Borneo. In 1703 (other sources say 1658), the Sultanate of Sulu received the eastern part of North Borneo from the Sultan of Brunei, after Sulu sent aid against a rebellion in Brunei.

Dutch and British control

The Sultanate of Brunei granted large parts of land in Sarawak in 1842 to the English adventurer James Brooke, as reward for his having helped quell a local rebellion. Brooke established the Kingdom of Sarawak and was recognised as its rajah after paying a fee to the Sultanate. He established a monarchy, and the Brooke dynasty (through his nephew and great-nephew) ruled Sarawak for 100 years; the leaders were known as the White Rajahs.[16]

In the early 19th century, British and Dutch governments signed the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 to exchange trading ports under their controls and assert spheres of influence. This resulted in indirectly establishing British- and Dutch-controlled areas in Borneo, in the north and south, respectively. The Malay and Sea Dayak pirates preyed on maritime shipping in the waters between Singapore and Hong Kong from their haven in Borneo.[17]

The British North Borneo Company controlled the territory of North Borneo (present-day Sabah) from 1882 to 1941.[18]

World War II

During World War II, Japanese forces gained control and occupied Borneo (1941–45). They decimated many local populations and killed Malay intellectuals, executing all the Malay Sultans of Kalimantan in the Pontianak incidents. Sultan Muhammad Ibrahim Shafi ud-din II of Sambas in Kalimantan was executed in 1944. The Sultanate was thereafter suspended and replaced by a Japanese council.[19] During the Japanese occupation, the Dayak played a role in guerrilla warfare against the occupying forces, particularly in the Kapit Division. They temporarily revived headhunting of Japanese toward the end of the war.[20] Allied Z Special Unit provided assistance to them. After the Fall of Singapore, the Japanese sent several thousand British and Australian prisoners of war to camps in Borneo. At one of the worst sites, around Sandakan in Borneo, only six of some 2,500 prisoners survived.[21] In 1945, the Japanese were defeated by the Allies.

Recent history

Borneo was the main site of the confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia between 1962 until 1969, as the Indonesian President at the time, Sukarno, perceived the presence of the British in the area as trying to maintain the colonial government, mostly because of Sukarno's own intention to control the whole Borneo island under the Greater Indonesian political concept. To counter this, the British deployed their armed forces to guard their colonies against Indonesian and communist revolts. The Philippines claimed the eastern part of North Borneo (today Malaysian state of Sabah) as part of its territory. The Philippine government based their claim on the Sultanate of Sulu's cession agreement with the British North Borneo Company, which stated that the Sultanate had come under the jurisdiction of the Philippine republican administration, and as such, the republic should be the inheritor of the Sulu territories. The area in northern Borneo was also subjected to attacks by Moro Pirates since the 18th century, and militants such as the Abu Sayyaf since 2000. In 1962, the Brunei People's Party led by A.M. Azahari desired to reunify Brunei, Sarawak and North Borneo into one federation known as the North Borneo Federation (Malay: Kesatuan Negara Kalimantan Utara), where the Sultan of Brunei would be the head of state for the federation, though Azahari had his own intention to abolish the Brunei Monarchy and integrate Brunei, along with other British former colonies in Borneo into Indonesia. This directly led to the Brunei Revolt and forced Azahari to escape to Indonesia, his attempts having failed.

Demographics

The demonym for Borneo is Bornean.

Borneo has 19.8 million inhabitants (in mid-2010), a population density of 26 inhabitants per square km. Most of the population lives in coastal cities, although the hinterland has small towns and villages along the rivers. The population consists mainly of Dayak ethnic groups, Malay, Banjar, Orang Ulu, Chinese and Kadazan-Dusun. The Chinese, who make up 29% of the population of Sarawak and 17% of total population in West Kalimantan, Indonesia[22] are descendants of immigrants primarily from southeastern China.[23]

In Kalimantan since the 1990s, the Indonesian government has undertaken an intense transmigration program; to that area it financed the relocation of poor, landless families from Java, Madura, and Bali. By 2001, transmigrants made up 21% of the population in Central Kalimantan.[24] Since the 1990s, the indigenous Dayak and Malays have resisted encroachment by these migrants: violent conflict has occurred between some transmigrant and indigenous populations. In the 1999 Sambas riots, Dayaks and Malays joined together to massacre thousands of the Madurese migrants. In Kalimantan, thousands were killed in 2001 fighting between Madurese transmigrants and the Dayak people in the Sampit conflict.[25]

Largest cities

The following is a list of 20 largest cities in Borneo by population, based on 2010 census for Indonesia[26][27] and 2010 census for Malaysia.[28] Population data signifies number within official districts and does not include adjoining or nearby conurbation outside defined districts—such as Kota Kinabalu and Banjarbaru. In other instances, the district area is much larger than the actual city it represents thereby "inflating" the population by including the rural population living further outside the actual city—such as Tawau and Palangkaraya.

| Rank | City/Town | Population | Density (/km2) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samarinda, East Kalimantan | 727,500 | 929 | Indonesia |

| 2 | Banjarmasin, South Kalimantan | 625,481 | 8,687 | Indonesia |

| 3 | Kuching, Sarawak | 617,886 | 332 | Malaysia |

| 4 | Balikpapan, East Kalimantan | 557,579 | 1,058 | Indonesia |

| 5 | Pontianak, West Kalimantan | 554,764 | 5,146 | Indonesia |

| 6 | Kota Kinabalu, Sabah | 462,963 | 1,319 | Malaysia |

| 7 | Tawau, Sabah | 412,375 | 67 | Malaysia |

| 8 | Sandakan, Sabah | 409,056 | 181 | Malaysia |

| 9 | Miri, Sarawak | 300,543 | 64 | Malaysia |

| 10 | Bandar Seri Begawan | 300,000 | 490 | Brunei |

| 11 | Sibu, Sarawak | 247,995 | 111 | Malaysia |

| 12 | Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan | 220,962 | 92 | Indonesia |

| 13 | Lahad Datu, Sabah | 206,861 | 28 | Malaysia |

| 14 | Banjarbaru, South Kalimantan | 199,627 | 538 | Indonesia |

| 15 | Tarakan, North Kalimantan | 193,370 | 771 | Indonesia |

| 16 | Bintulu, Sarawak | 189,146 | 26 | Malaysia |

| 17 | Singkawang, West Kalimantan | 186,462 | 370 | Indonesia |

| 18 | Keningau, Sabah | 177,735 | 50 | Malaysia |

| 19 | Bontang, East Kalimantan | 143,683 | 353 | Indonesia |

| 20 | Victoria, Labuan | 85,272 | 950 | Malaysia |

Administration

The island of Borneo is divided administratively by three countries.

- The Indonesian provinces of East, South, West, North and Central Kalimantan, Kalimantan

- The Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak (The Malaysian Federal Territory of Labuan is located on nearshore islands of Borneo.)

- The independent country of Brunei (main part and eastern exclave of Temburong)

| Federal State or Province |

Capital | Part of country | Area km2 |

Area % |

Population censuses of 2010[29][30] 3 |

Population % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei | Bandar Seri Begawan | Independent Sultanate | 5,770 | 0.77 | 406,200 (2009 est)[31] |

2.1 |

| Sarawak | Kuching | Malaysia | 124,450 | 16.55 | 2,420,009 | 12.2 |

| Sabah | Kota Kinabalu | Malaysia | 73,619 | 9.79 | 3,120,040 | 15.7 |

| Labuan | Victoria | Malaysia Federal territory |

92 | 0.01 | 85,272 | 0.4 |

| East Malaysia | Malaysia | 198,161 | 26.4 | 5,625,321 | 28.4 | |

| West Kalimantan | Pontianak | Indonesia | 146,760 | 19.5 | 4,393,239 | 22.2 |

| Central Kalimantan | Palangkaraya | Indonesia | 152,600 | 20.3 | 2,202,599 | 11.1 |

| South Kalimantan | Banjarmasin | Indonesia | 37,660 | 5.0 | 3,626,119 | 18.3 |

| East Kalimantan | Samarinda | Indonesia | 210,985 | 28.1 | 3,550,586 | 17.9 |

| North Kalimantan | Tanjung Selor | Indonesia | 71,177 | 9.46 | 525,000 | 2.65 |

| Kalimantan | Indonesia | 548,005 | 72.9 | 13,772,543 | 69.5 | |

| Borneo | – | 3 countries | 751,936 | 100.0 | 19,804,064 | 100.0 |

1) Brunei: Census of Population 2001

2) islands administered as Borneo, geologically part of Borneo, on nearshore islands (2.5 km off the main island of Borneo)

3) Citypopulation.de reports on Official Decennial Censuses in 2010 for both Indonesia and Malaysia, independent estimate for Brunei.

See also

- Fauna of Borneo

- Flora of Borneo

- Hikayat Banjar

- Kutai basin

- List of endemic birds of Borneo

- List of islands of Indonesia

- List of islands of Malaysia

- Mammals of Borneo

- Maphilindo

References

- ↑ "10 largest islands in the world". http://10mosttoday.com. External link in

|journal=(help) - ↑ "Central Kalimantan Province". archipelago fastfact. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ History for Brunei 2009, p. 43

- ↑ "Naskah Nagarakretagama" (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "An Awesome Island". Borneo: Island in the Clouds. PBS. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ BBC-TV: "Borneo", Planet Earth

- ↑ MacKinnon, K; et al. (1998). The Ecology of Kalimantan. London: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Nguyen, T.T.T., and S. S. De Silva (2006). "Freshwater Finfish Biodiversity and Conservation: An Asian Perspective", Biodiversity & Conservation 15(11): 3543-3568

- ↑ "Scientists discover new species in Heart of Borneo". WWF. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Shayne Heffernan (21 October 2010). "Economy Malaysia, Eyes on Sarawak". Live Trading News. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Cœdès, George (1968). The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824803681.

- ↑ Derek Heng Thiam Soon (June 2001). "The Trade in Lakawood Products Between South China and the Malay World from the Twelfth to Fifteenth Centuries AD". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000066.

- 1 2 Jan O. M. Broek (1962). "Place Names in 16th and 17th Century Borneo". Imago Mundi. 16: 129–148. doi:10.1080/03085696208592208. JSTOR 1150309.

- ↑ (Chapter 15) The Earliest Indic State: Kutai. The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. E Press, The Australian National University. 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "1350-1400 - Majapahit Empire". Military. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "Part 2 - The Brooke Era". The Borneo Project. Earth Island Institute. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Wanderings Among South Sea Savages And in Borneo and the Philippines by H. Wilfrid Walker. Archived from the original on November 4, 2009.

- ↑ "British North Borneo Papers". School of Oriental and African Studies. Archives hub. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ http://pariwisata.kalbar.go.id/index.php?op=deskripsi&u1=1&u2=1&idkt=4

- ↑ "'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail", New York Times, 9 November 2007. Archived 21 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Japanese Prisoners of War. Philip Towle, Margaret Kosuge, Yōichi Kibata (2000). Continuum International Publishing Group. pp.47–48. ISBN 1-85285-192-9.

- ↑ "Province of West Kalimantan, Indonesia". Guangdong Foreign Affairs Office.

- ↑ "The world's successful diasporas", Management Today. 3 April 2007.

- ↑ "Indonesia flashpoints:, Kalimantan". BBC. 28 June 2004. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ↑ "Beheading: A Dayak ritual". BBC. 23 February 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ↑ "Sensus Penduduk 2010" (PDF). Badan Pusat Statistik, Indonesia. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Administrative Division Indonesia: Provinces, Regencies and Cities - Statistics & Maps by »City Population«". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics, 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ "Malaysia: Federal States, Territories, Major Cities & Conurbations – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia (Urban Municipality Population): Provinces, Cities & Municipalities – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ↑ "Brunei: Districts, Major Cities, Towns & Agglomeration – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

Further reading

- Ghazally Ismail et al. (eds.) Scientific Journey Through Borneo Series. Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Kota Samarahan. 1996–2001.

- Gudgeon, L. W. W. British North Borneo. Adam and Charles Black, London, 1913.(An early, well-illustrated book on "British North Borneo", now known as Sabah)

- Mathai, J., Hon, J., Juat, N., Peter, A., & Gumal, M. 2010. "Small carnivores in a logging concession in the Upper Baram, Sarawak, Borneo," Small Carnivore Conservation 42: 1–9.

- K M Wong & C L Chan. "Mt Kinabalu: Borneo's Magic Mountain." Natural History Publications, Kota Kinabalu. 1998.

- Dennis Lau. Borneo: A Photographic Journey.

- Stephen Holley. "White Headhunter in Borneo", in Robert Young Pelton, Borneo.

- Mel White: " Borneo's moment of truth", National Geographic Magazine, November 2008.

- Mathai, J. 2010. "Hose's Civet: Borneo's mysterious carnivore". Nature Watch 18/4: 2–8.

- Robert Young Pelton. Fielding's Borneo

- Eric Hansen. Stranger in the Forest: On Foot Across Borneo.

- John Wassner. Espresso with the Headhunters: A Journey Through the Jungles of Borneo.

- Redmond O'Hanlon. Into the Heart of Borneo: An Account of a Journey Made in 1983 to the Mountains of Batu Tiban with James Fenton.

- Charles M. Francis. A Photographic Guide to Mammals of South-east Asia.

- Abdullah, MT. "Biogeography and variation of Cynopterus brachyotis in Southeast Asia." PhD thesis. The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia. 2003.

- Corbet, GB, Hill JE. The mammals of the Indomalayan region: a systematic review. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1992.

- G.W.H. Davison, Chew Yen Fook. A Photographic Guide to Birds of Borneo.

- Hall LS, Gordon G. Grigg, Craig Moritz, Besar Ketol, Isa Sait, Wahab Marni and MT Abdullah. "Biogeography of fruit bats in Southeast Asia." Sarawak Museum Journal LX(81):191–284. 2004.

- Karim, C., A.A. Tuen and M.T. Abdullah. "Mammals." Sarawak Museum Journal Special Issue No. 6. 80: 221–234. 2004.

- Garbutt, Nick, and J. Cede Prudente. Wild Borneo: The Wildlife and Scenery of Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei, and Kalimantan. 2007.

- Mohd. Azlan J., Ibnu Maryanto, Agus P. Kartono, and MT Abdullah. "Diversity, Relative Abundance and Conservation of Chiropterans in Kayan Mentarang National Park, East Kalimantan, Indonesia." Sarawak Museum Journal 79: 251–265. 2003.

- Hall LS, Richards GC, Abdullah MT. "The bats of Niah National Park, Sarawak." Sarawak Museum Journal. 78: 255–282. 2002.

- Nieuwenhuis, A.W. Quer Durch Borneo

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Borneo. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Borneo. |

- Environmental Profile of Borneo – Background on Borneo, including natural and social history, deforestation statistics, and conservation news.