British war crimes

British war crimes are proven acts by the armed forces of the United Kingdom which have violated the laws and customs of war since the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Such acts have included the summary executions of prisoners of war and unarmed shipwreck survivors, the use of excessive force during the interrogation of POWs and enemy combatants, and the use of violence against civilian non-combatants and their property . Although numerous documented cases are known, British war crimes remains less widely known than those committed by the armed forces of other nations.

In commenting on the alleged massacre of a shipwrecked U-Boat crew during World War I,[1] historian Geoffrey Brooks alleged that an unofficial policy has contributed to this. According to Brooks, "It is not, and never has been, the practice of the British military authorities to try British service personnel for alleged war crimes committed against enemy belligerents in wartime no matter how strong the evidence."[2] Numerous British service personnel, however, have been subjected to court martial proceedings and in some cases convicted and even executed for war crimes. Furthermore, questions about alleged war crimes have also been raised by Opposition MPs in the House of Commons, particularly during the Second Boer War and the Irish War of Independence.

Definition

War crimes are defined as acts which violate the laws and customs of war (established by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907), or acts that are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I and Additional Protocol II.[3] The Fourth Geneva Convention extends the protection of civilians and prisoners of war during military occupation, even in the case where there is no armed resistance, for the period of one year after the end of hostilities, although the occupying power should be bound to several provisions of the convention as long as "such Power exercises the functions of government in such territory."[4][5]

The Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict published by the UK Ministry of Defence[6] uses the 1945 definition from the Nuremberg Charter, which defines a war crime as "Violations of the laws or customs of war. Such violations shall include, but not be limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labour or for any other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity."[3] The manual also notes that "violations of the 1949 Geneva Conventions not amounting to 'grave breaches' are also war crimes."

The 2004 Laws of Armed Combat Manual says

Serious violations of the law of armed conflict, other than those listed as grave breaches in the [1949 Geneva] Conventions or [the 1977 Additional Protocol I], remain war crimes and punishable as such. A distinction must be drawn between crimes established by treaty or convention and crimes under customary international law. Treaty crimes only bind parties to the treaty in question, whereas customary international law is binding on all states. Many treaty crimes are merely codifications of customary law and to that extent binding on all states, even those that are not parties.

The 2004 publication also notes that "A person is normally only guilty of a war crime if he commits it with intent and knowledge."[7]

Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901, including the aftermath of the Battle of Peking, troops from the Eight-Nation Alliance, including British ones, committed war crimes while stationed in China. Author Bertram Lenox Simpson, who was in China at the time, reported that he came across "a whole company of savage-looking British and Indian troops" molesting a group of female converts "green-white with fear" while a lady missionary vainly tried to beat them off with an umbrella. Troops also looted with many of the stolen items ending up in Europe.[8][9]

The South African War

Counterinsurgency

As part of the strategy to defeat the guerrilla warfare of the Boer Commandos, farms were destroyed to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. This included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock,[10] the burning down of homesteads, poisoning of wells and salting of fields.

In response to a Parliamentary report on the destruction of Boer farms, anti-war activist Frederic Harrison wrote a letter to the Daily News, published on 30 May 1901, "The official return has disclosed a barbarous, vindictive, systematic attempt to terrorise and crush a brave enemy in arms, by devastating a country which it was found impossible to conquer, by ruining the homes of soldiers with whom we were waging war, and by exposing their wives and children to misery and want. This was a violation of the recognised laws of civilised war, and was expressly forbidden by the Hague Conference. It was especially infamous when resorted to against an honorable body of citizens who were defending the existence of their country. It was insane folly in the case of a people whom it was designed to incorporate into the Empire, who had actually been proclaimed as our own fellow countrymen."[11]

Destruction of towns

Ventersburg

On 26 October 1900, William Williams, a British justice of the peace at Ventersburg in the former Orange Free State, passed a secret message to Maj. Edward Pine-Coffin, alleging that Boer Commandos were concentrating in the village. Maj. Pine-Coffin passed the message on to Field Marshal Lord Frederick Roberts, who decreed that, "an example should be made of Ventersburg".[12]

On 28 October, Field Marshal Roberts issued orders to General Bruce Hamilton, that all houses belonging to absent males were to be burned down. After burning down the village and its Dutch Reformed church, Gen. Hamilton posted the following bulletin, "The town of Ventersburg has been cleansed of supplies and partly burnt, and all the farms in the vicinity destroyed, on account of the frequent attacks on the railway lines in the neighborhood. The Boer women and children who are left behind should apply to the Boer Commandants for food, who will supply them unless they wish to see them starve. No supplies will be sent from the railway to the town."[13]

On 1 November 1900, Maj. Pine-Coffin in his diary that the remaining civilian population of Ventersburg had been transported to concentration camps. He admitted to have made sure that families were divided and that male and female Afrikaners were sent to different locations, "so that after the war they will have some difficulty in getting together."[13]

The destruction of Ventersburg was denounced in the House of Commons by Liberal MP David Lloyd George, who said of Gen. Hamilton, "This man is a brute and a disgrace to the uniform he wears."[14]

Louis Trichardt

On 9 May 1901, Cols . Johan William Colenbrander and H.L. Grenfell rode into Louis Trichardt ahead of a mixed force of about 600 men. In addition to Kitchener's Fighting Scouts, the force included elements of the Pietersburg Light Horse, the Wiltshire Regiment, the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC), a large force of Black South African" Irregulars", and six members of the War Office's Intelligence Department commanded by Captain Alfred James Taylor.[15]

Even though Louis Trichardt was "reeling from the annual effects of malaria", British and Commonwealth servicemen sacked the town and arrested an estimated 90 male residents suspected of links to the Zoutpansberg Commando.[16]

On 11 May 1901, the remaining residents of Louis Trichardt, including both the Afrikaner and "Cape Coloured" populations, were ordered to evacuate the town. According to local resident E.R. Smith, British and Commonwealth servicemen helped themselves to whatever "curios" they wanted and allowed the civilian population only a short time to gather their things. The town of Louis Trichardt was then burned down by Native South African "Irregulars" under the supervision of Captain Taylor. The civilian population was force marched between 11 and 18 May to the British concentration camp at Pietersburg.[17]

According to South African historian Charles Leach, Captain Taylor "emphatically told" the local Venda and Sotho communities "to help themselves to the land and whatever else they wanted as the Boers would not be returning after the war."[18]

Concentration camps

As a further strategy, General Lord Kitchener ordered the creation of concentration camps - 45 for Afrikaners and 64 for Black Africans.

According to historian Thomas Pakenham, "In practice, the farms of Boer collaborators got burnt too - burnt by mistake by Tommies or in reprisal by the commandos. So Kitchener added a new twist to farm-burning. He decided that his soldiers should not only strip the farms of stock, but should take the families, too. Women and children would be concentrated in 'camps of refuge' along the railway line. In fact, these camps consisted of two kinds of civilians: genuine refugees - that is, the families of Boers who were helping the British, or at least keeping their oath of neutrality - and internees, the families of men who were still out on commando. The difference was crucial, for at first there were two different scales of rations: little enough in practice for the refugees, and a recklessly low scale for the internees."[19]

Of the 107,000 people interned in the camps, 27,927 Boer women and children died [20] as well as more than 14,000 Black Africans.[21]

The Pietersburg War Crimes Trials

The Boer War also saw the first war crimes prosecutions in British military history. They centered around the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC), a British Army irregular regiment of mounted rifles active in the Northern Transvaal. Originally raised in February 1901, the BVC was composed mainly of British and Commonwealth servicemen with a generous admixture of defectors from the Boer Commandos.[22] After more than a century, the ensuing court martials remain controversial.

The Letter

On 4 October 1901, a letter signed by 15 members of the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) garrison at Fort Edward was secretly dispatched to Col. F.H. Hall, the British Army Officer Commanding at Pietersburg. Written by BVC Trooper Robert Mitchell Cochrane, a former Justice of the Peace from Western Australia,[23][24] the letter accused members of the Fort Edward garrison of six "disgraceful incidents":

1. The shooting of six surrendered Afrikaner men and boys and the theft of their money and livestock at Valdezia on 2 July 1901. The orders had been given by Captains Alfred Taylor and James Huntley Robertson, and relayed by Sgt. Maj. K.C.B. Morrison to Sgt. D.C. Oldham. The actual killing was alleged to have been carried out by Sgt. Oldham and BVC Troopers Eden, Arnold, Brown, Heath, and Dale.[25]

2. The shooting of BVC Trooper B.J. van Buuren by BVC Lt. Peter Handcock on 4 July 1901. Trooper van Buuren, an Afrikaner, had "disapproved" of the killings at Valdezia, and had informed the victims' wives and children, who were imprisoned at Fort Edward, of what had happened.[26]

3. The revenge killing of Floris Visser, a wounded prisoner of war, near the Koedoes River on 11 August 1901. Visser had been captured by a BVC patrol let by Lieut. Harry Morant two days before his death. After Visser had been exhaustively interrogated and conveyed for 15 miles by the patrol, Lt. Morant had ordered his men to form a firing squad and shoot him. The squad consisted of BVC Troopers A.J. Petrie, J.J. Gill, Wild, and T.J. Botha. A coup de grâce was delivered by BVC Lt. Harry Picton. The slaying of Floris Visser was in retaliation for the combat death of Morant's close friend, BVC Captain Percy Frederik Hunt, at Duivelskloof on 6 August 1901.[27]

4. The shooting, ordered by Capt. Taylor and Lt. Morant, of four surrendered Afrikaners and four Dutch schoolteachers, who had been captured at the Elim Hospital in Valdezia, on the morning of 23 August 1901. The firing squad consisted of BVC Lt. George Witton, Sgt. D.C. Oldham, and Troopers J.T. Arnold, Edward Brown, T. Dale, and A. Heath. Although Trooper Cochrane's letter made no mention of the fact, three Native South African witnesses were also shot dead.[28]

The ambush and fatal shooting of the Reverend Carl August Daniel Heese of the Berlin Missionary Society near Bandolierkop on the afternoon of 23 August 1901. Rev. Heese had spiritually counseled the Dutch and Afrikaner victims that morning and had angrily protested to Lt. Morant at Fort Edward upon learning of their deaths. Trooper Cochrane alleged that the killer of Rev. Heese was BVC Lt. Peter Handcock. Although Cochrane made no mention of the fact, Rev. Heese's driver, a member of the Southern Ndebele people, was also killed.[29]

5. The orders, given by BVC Lt. Charles H.G. Hannam, to open fire on a wagon train containing Afrikaner women and children who were coming in to surrender at Fort Edward, on 5 September 1901. The ensuing gunfire led to the deaths of two boys, aged 5- and 13-years, and the wounding of a 9-year-old girl.[30]

6. The shooting of Roelf van Staden and his sons Roelf and Christiaan, near Fort Edward on 7 September 1901. All were coming in to surrender in the hope of gaining medical treatment for teenaged Christiaan, who was suffering from recurring bouts of fever. Instead, they were met at the Sweetwaters Farm near Fort Edward by a party consisting of Lts. Morant and Handcock, joined by BVC Sgt. Maj. Hammet, Corp. MacMahon, and Troopers Hodds, Botha, and Thompson. Roelf van Staden and both his sons were then shot, allegedly after being forced to dig their own graves.[31]

The letter then accused the Field Commander of the BVC, Major Robert Lenahan, of being "privy the these misdeamenours. It is for this reason that we have taken the liberty of addressing this communication direct to you." After listing numerous civilian witnesses who could confirm their allegations, Trooper Cochrane concluded, "Sir, many of us are Australians who have fought throughout nearly the whole war while others are Africaners who have fought from Colenso till now. We cannot return home with the stigma of these crimes attached to our names. Therefore we humbly pray that a full and exhaustive inquiry be made by Imperial officers in order that the truth be elicited and justice done. Also we beg that all witnesses may be kept in camp at Pietersburg till the inquiry is finished. So deeply do we deplore the opprobrium which must be inseparably attached to these crimes that scarcely a man once his time is up can be prevailed to re-enlist in this corps. Trusting for the credit of thinking you will grant the inquiry we seek."[32]

Arrests

In response to the letter written by Trooper Cochrane, Col. Hall summoned all Fort Edward officers and non-commissioned officers to Pietersburg on 21 October 1901. All were met by a party of mounted infantry five miles outside Pietersburg on the morning of 23 October 1901 and "brought into town like criminals". Lt. Morant was arrested after returning from leave in Pretoria, where he had gone to settle the affairs of his deceased friend Captain Hunt.[33]

Indictments

Although the trial transcripts, like almost all others dating from between 1850 and 1914, were later destroyed by the British civil service,[34] it is known that a Court of Inquiry, the British military's equivalent to a grand jury, was convened on 16 October 1901. The President of the Court was Col. H.M. Carter, who was assisted by Captain E. Evans and Major Wilfred N. Bolton, the Provost Marshal of Pietersburg. The first session of the Court took place on 6 November 1901 and continued for four weeks. Deliberations continued for a further two weeks,[35] at which time it became clear that the indictments would be as follows:

1. In what became known as "The Six Boers Case", Captains Robertson and Taylor, as well as Sgt. Maj. Morrison, were charged with committing the offense of murder while on active service.[36]

2. In relation to what was dubbed "The Van Buuren Incident", Maj. Lenahan was charged with, "When on active service by culpable neglect failing to make a report which it was his duty to make."[37]

3. In relation to "The Visser Incident", Lts. Morant, Handcock, Witton, and Picton were charged with "While on active service committing the offense of murder".[38]

4. In relation to what was incorrectly dubbed "The Eight Boers Case", Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton were charged with, "While on active service committing the offense of murder".[39]

In relation to the slaying of Rev Heese, Lts. Morant and Handcock were charged with, "While on active service committing the offense of murder".

5. No charges were filed for the three children who had been shot by the Bushveldt Carbineers near Fort Edward.[40]

6. In relation to what became known as "The Three Boers Case", Lts. Morant and Handcock were charged with, "While on active service committing the offense of murder".[39]

Court Martials

Following the indictments, Maj. R. Whigham and Col. James St. Clair ordered Bolton to appear for the prosecution, as he was considered less expensive than hiring a barrister.[41] Bolton vainly requested to be excused, writing, "My knowledge of law is insufficient for so intricate a matter."[42]

The first court martial opened on 16 January 1901, with Lieut.-Col. H.C. Denny presiding over a panel of six judges. Maj. J.F. Thomas, a Solicitor from Tenterfield, New South Wales, had been retained to defend Maj. Lenahan. The night before, however, he agreed to represent all six defendants.[35]

The "Visser Incident" was the first case to go to trial. Lt. Morant's former orderly and interpreter, BVC Trooper Theunis J. Botha, testified that Visser, who had been promised that his life would be spared, was cooperative during two days of interrogation and that all his information was later found to have been true. Despite this, Lt. Morant ordered him shot.[43]

In response, Lt. Morant testified that he only followed orders to take no prisoners as relayed to the late Captain Hunt by Col. Hubert Hamilton. He also alleged that Floris Visser had been captured wearing a British Army jacket and that Captain Hunt's body had been mutilated.[44] In response, the court moved to Pretoria, where Col. Hamilton testified that he had "never spoken to Captain Hunt with reference to his duties in the Northern Transvaal". Though stunned, Maj. Thomas argued that his clients were not guilty because they believed that they "acted under orders". In response, Maj. Bolton argued that they were "illegal orders" and said, "The right of killing an armed man exists only so long as he resists; as soon as he submits he is entitled to be treated as a prisoner of war." The Court ruled in Maj. Bolton's favor.[45] Lt. Morant was found guilty of murder. Lts. Handcock, Witton, and Picton were convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter.[46]

Execution

On 27 February 1902, two British Army Lieutenants — Anglo-Australian Harry Morant and Australian born Peter Handcock of the Bushveldt Carbineers — were executed by firing squad after being convicted of murdering eight Afrikaner POWs. This court-martial for war crimes was one of the first such prosecutions in British military history.

Although Morant left a written confession in his cell, he went on to become a folk hero in modern Australia. Believed by many Australians to be the victim of a kangaroo court, public appeals have been made for Morant to be retried or pardoned. His court-martial and death have been the subject of books, a stage play, and an award-winning Australian New Wave film adaptation by director Bruce Beresford.

Reaction in Britain

The subject of British war crimes was first raised in the House of Commons by MPs from the Irish Parliamentary Party the "Radical" faction of the Liberal Party.

On March 1, 1901,[19] Lloyd George quoted a Reuters report about the lower rations given to the interned families of Boer Commandos. "It means," declared Lloyd George, "that unless the fathers come in their children would be half-starved. It means that the remnant of the Boer army who are sacrificing everything for their idea of independence are to be tortured by the spectacle of their starving children into betraying their cause."[47] During the same month, Liberal MPs C.P. Scott and John Ellis dubbed them "concentration camps", after the reconcentrado camps set up by the Spanish during the Cuban War of Independence.[47]

World War I

According to American historian Alfred de Zayas, both sides during the Great War "established, for judicial and political reasons, special commissions to investigate reported instances of war crimes by enemy forces."[48] In contrast to their Allied counterparts, German investigators rarely publicized their findings for propaganda purposes.[49] Furthermore, all except 11 volumes of the German Bureau's World War I archives were destroyed during the 1945 Allied bombing raids on Berlin and Potsdam.[50] For these reasons, British war crimes during the Great War remain less widely known than their German equivalents and are far more difficult to research.

Chemical weapons usage

The production and use of chemical weapons was strictly prohibited by the 1899 Hague Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases and the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, which explicitly forbade the use of "poison or poisoned weapons" in warfare.[51][52]

Even so, the United Kingdom used a range of poison gases, originally chlorine and later phosgene, diphosgene and mustard gas. They also used relatively small amounts of the irritant gases chloromethyl chloroformate, chloropicrin, bromacetone and ethyl iodoacetate. Gases were frequently mixed, for example white star was the name given to a mixture of equal volumes of chlorine and phosgene, the chlorine helping to spread the denser but more toxic phosgene. Despite the technical developments, chemical weapons suffered from diminishing effectiveness as the war progressed because of the protective equipment and training which the use engendered on both sides. By 1918, a quarter of British artillery shells were filled with gas and the United Kingdom had produced around 25,400 tons of toxic chemicals.

The British Expeditionary Force first used chemical weapons along the Western Front at the Battle of Loos on 25 September 1915 and continued their usage for the remainder of the war. This was done in retaliation for the use of chlorine by Imperial German Army the preceding April.

Following the Imperial German Army's use of poison gas at Ypres, the commander of II Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Charles Ferguson, had said of poison gas:

It is a cowardly form of warfare which does not commend itself to me or other English soldiers ... We cannot win this war unless we kill or incapacitate more of our enemies than they do of us, and if this can only be done by our copying the enemy in his choice of weapons, we must not refuse to do so.[53]

Mustard gas was first used effectively in World War I by the German army against British and Canadian soldiers near Ypres, Belgium, in 1917 and later also against the French Second Army. The name Yperite comes from its usage by the German army near the town of Ypres. The Allies did not use mustard gas until November 1917 at Cambrai, France, after the armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard-gas shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard gas weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on Avonmouth Docks.[54][55] (The only option available to the British was the Despretz–Niemann–Guthrie process). This was used first in September 1918 during the breaking of the Hindenburg Line with the Hundred Days' Offensive.

War Crimes at Sea

During the German U-boats campaign against unarmed, merchant shipping, there were numerous incidents in which the Royal Navy violated the Hague Convention of 1907's prohibition against killing unarmed shipwreck survivors under any circumstances. According to historian Paul G. Halpern, the most infamous of these incidents "... became one of the most celebrated of the war and a German justification for the adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare."[56]

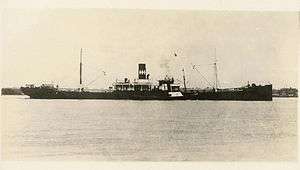

SM U-27

After the sinking of RMS Lusitania by the German submarine U-20 in May 1915, Lieutenant-Commander Godfrey Herbert, commanding officer of the Q-ship HMS Baralong, was visited by two officers of the Admiralty's Secret Service branch at the naval base at Queenstown, Ireland. He was told, "This Lusitania business is shocking. Unofficially, we are telling you ... take no prisoners from U-boats."[57] Since April 1915, Herbert had ordered his subordinates cease calling him "Sir", and to address him only by the pseudonym "Captain William McBride."[58]

On 19 August 1915, the German submarine U-27 surfaced, stopped, and searched the Nicosian, a British freighter, 70 nautical miles off the coast of Queenstown. After finding the Nicosian loaded with war materiel and mules bound for the British Expeditionary Force in France, the U-27's commanding officer, Kapitänleutnant Bernhard Wegener, instructed the Nicosian's Captain and crew to take to the lifeboats.

As Wegener and his men prepared to sink the now-empty Nicosian with their deck gun, the Baralong arrived, flying the neutral American flag as a ruse of war. After lowering that flag and raising the British White Ensign in its place, Baralong's crew opened fire and sank the U-27.

Twelve German sailors survived the U-27's sinking: the crews of her two deck guns and those who had been on the conning tower. They swam to Nicosian and attempted to join the six-man boarding party by climbing up her hanging lifeboat falls[note 1] and pilot ladder. In response, Herbert ordered his men to open fire with small arms on the men in the water.[59][60][61][62]

After a few German survivors managed to climb aboard the Nicosian, Herbert sent Baralong's 12 Royal Marines, under the command of a Corporal Collins, to board the sinking vessel. As they departed, Herbert ordered Collins, "Take no prisoners."[63] The Germans were discovered in the engine room and shot on sight. According to Sub-Lieutenant Gordon Steele: "Wegener ran to a cabin on the upper deck - I later found out it was Manning's bathroom. The marines broke down the door with the butts of their rifles, but Wegener squeezed through a scuttle and dropped into the sea. He still had his life-jacket on and put up his arms in surrender. Corporal Collins, however, took aim and shot him through the head."[64] Collins later recalled that, after Wegener's death, Herbert threw a revolver in the German captain's face and screamed, "What about the Lusitania, you bastard!"[64]

In Herbert's report to the Admiralty, he alleged the German survivors were trying to board and scuttle the Nicosian, so he ordered the Royal Marines on his ship to kill the survivors. The Admiralty, upon receiving the report, vainly ordered that the incident be kept secret.

After the Nicosian's crew arrived at Liverpool, however, the American members of the crew gave sworn testimony to the United States Consul about the massacre of U-27's crew. After their return to the United States, they repeated their testimony before a notary public at the Imperial German Consulate in New Orleans. As a result, the US State Department forwarded a formal protest by the German Empire to the British Foreign Office.[65]

The memorandum demanded that "Captain McBride" and the crew of HMS Baralong be court-martialed and threatened to "take the serious decision of retribution" if the massacre of U-27's crew went unprosecuted.[66]

The Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, replied through U.S. State Department in a textbook example of diplomatic effrontery. He wrote, "His Majesty's Government do not think it necessary to make any reply to the suggestion that the British navy has been guilty of inhumanity, according to the latest figures available, the number of German sailors rescued from drowning, often in circumstances of great difficulty and peril, amounts to 1,150. The German navy can show no such record - perhaps through want of opportunity."[67]

Sir Edward further argued that the alleged massacre of U-27's crew could be grouped with the Imperial German Navy's sinking of SS Arabic, their attack on a stranded British submarine in neutral Dutch territorial waters, and their attack on the steamship Ruel. In conclusion, Grey suggested that all four incidents be placed before a tribunal chaired by the United States Navy.[68]

The U.S. State Department also vainly protested that the American flag had been used as a false flag. Walter Hines Page, the U.S. Ambassador in London, was telegraphed by Secretary of State Robert Lansing and ordered to not ask Sir Edward Grey any questions about whether the American flag had been used in the case. "The fact," he was told, "is established.[67]

Lieutenant Commander Herbert and the crew of HMS Baralong were awarded a bounty of £185 for sinking U-27.[69]

SM U-41

On 24 September 1915 HMS Baralong also sank U-41, which was in the process of sinking the cargo ship Urbino. According to the two German survivors, Baralong continued to fly the American flag after opening fire on U-41 and then rammed the lifeboat carrying the German survivors, causing it to sink.[70] The only witnesses to the second attack were the German and British sailors present. Oberleutnant zur See Iwan Crompton, after returning to Germany from a prisoner-of-war camp, reported that Baralong had run down the lifeboat he was in; he leapt clear and was shortly after taken prisoner. The British crew denied that they had rammed the lifeboat.[71] Crompton later published an account of U-41's exploits in 1917, U-41: der zweite Baralong-Fall (Eng: "The second Baralong case").[72]

Baralong's new commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander A. Wilmot-Smith, and his crew were awarded a £170 bounty for sinking U-41.[73]

The Easter Rising

On Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, a combined force of the Irish Volunteers, led by Patrick Pearse, and James Connolly's Irish Citizen Army seized key locations in Dublin and proclaimed Ireland an independent Republic. This led to a citywide battle between Irish Republican forces and the British Army.

During the six days of fighting, British servicemen stationed at Portobello Barracks violated the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions on the Laws and Customs of Warfare on Land, which guarantee the lives and property of civilians during military combat.

The violations began on the evening of 25 April 1916, when Captain J. C. Bowen-Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles decided to go on a search for "Fenians". Dublin residents Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, Thomas Dickson, and Patrick McIntyre had been arrested earlier that day for suspected Republican sympathies and Captain Bowen-Colthurst demanded they accompany him as hostages.[74]

Upon seeing a 17-year-old boy, Captain Bowen-Colthurst ordered his men to, "Bash him", watched as they did so, and then fatally shot the boy as he lay in the street. Sheehy-Skeffington, a pacifist who had recently attempted to save a British officer who had been wounded and pinned down by Republican fire outside the Dublin General Post Office, angrily protested and was told by the Captain, "You'll be next."

Captain Bowen-Colthurst went on to also kill a union leader, Councillor Richard O'Carroll, and another boy. He also had the tobacco shop of Alderman James Kelly destroyed with grenades.

On the morning of 26 April 1916, Sheehy-Skeffington, Dickson, and McIntyre were shot by an ad hoc firing squad in the courtyard of Portobello Barracks. Dickson and McIntyre had both been Pro-British journalists; Sheehy-Skeffington had been an advocate of Irish Home Rule within the United Kingdom. All three bodies were put in sacks and buried in the barracks yard.[75]

Three days later, Pearse ordered an unconditional surrender after six days of fighting. The leaders of what became known as the Easter Rising were court martialed and executed by firing squad and large numbers of real and imagined Republicans were rounded up and sent to Frongoch internment camp in Wales.

Meanwhile, the commander of Portobello Barracks, Major Sir Francis Fletcher-Vane of the Royal Munster Fusiliers had learned of the actions of his subordinates. Regarding Captain Bowen-Colthurst's actions as tantamount to murder, the Major decided to arrest him. To the Major's shock and horror, both Dublin Castle and their military superiors refused permission. The Major was advised that Sheehy-Skeffington had been a political troublemaker who deserved what he got.

In response, Major Fletcher-Vane traveled to London and obtained a direct order for the Captain's arrest from Lord Kitchener. In Dublin, General Sir John Maxwell, the military governor of Ireland with "plenary powers" under "Martial law", simply ignored it.[76] In a British Army briefing which still survives, it was decided that Major Fletcher-Vane "is to be reduced to unemployment owing to his actions in the Sheehy-Skeffington case." Both the Prime Minister and King George V rejected calls for his reinstatement.[74]

The Royal Military Police finally arrested Captain Bowen-Colthurst on 6 June 1916, after Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington appealed directly to British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith. In a court martial widely seen as a miscarriage of justice, Captain Bowen-Colthurst pleaded insanity based on his combat experiences in the trenches. He was found guilty of murder, but insane, and was committed to Broadmoor Hospital. Captain J.C. Bowen-Colthurst was released as cured in 1921 and retired to Canada on a full pension.[76]

German Investigation of British War Crimes

According to historian Alfred de Zayas, the Prussian Ministry of War established the "Military Bureau for the Investigation of Violations of the Laws of War", (German: Militäruntersuchungstelle für Verletzungen des Kriegsrechts) on 19 October 1914. The Bureau's stated purpose was "to determine violations of the laws and customs of war which enemy military and civilian persons have committed against the Prussian troops and to investigate whatever accusations of this nature are made against by the enemy against members of the Prussian Army."[77]

The Military Bureau "had wide competence to establish facts in a judicial manner and to secure the evidence necessary for legal analysis of each case. Witnesses were interrogated and their sworn depositions taken by military judges; lists of suspected war criminals were compiled, which would probably have led to criminal proceedings if Germany had won the war. The material remained largely secret, though some excerpts from witness depositions were used in German white books."[77]

By the summer of 1918, the Military Bureau had documented 355 separate incidents of violations of the laws and customs of war by British servicemen along the Western Front.[78]

The Military Bureau also compiled a thirteen-page "Black List of Englishmen who are guilty of violations of the laws of war vis a vis members of the German Armed Forces" (German: Schwarze Liste derjenigen Engländer, die sie während des Krieges gegenüber deutschen Heeresangehörigen völkerechtwidringen Verhaltens schuldig gemacht haben). The list, which survived the Allied firebombing of Berlin and Potsdam during the Second World War, contains a total of 39 names, including "Captain McBride" of HMS Baralong. In contrast, however, nine similar lists survive of alleged French war criminals and consist of 400 names.[79]

Following the Armistice, investigation continued, particularly into crimes against German POWs, and culminated in a five volume report entitled International Law during the World War (German: Völkerrecht im Weltkrieg). The report was never translated, however, and had minimal effect outside of Germany.[80]

Also following the Armistice, the victorious Allies pooled their reports, compiled a joint list of alleged German war crimes, and demanded the extradition of 900 alleged war criminals for trial in France and the United Kingdom. As this proved unacceptable to the German electorate, the Government of the Weimar Republic agreed to try them domestically in the Leipzig War Crimes Trials.[81]

According to de Zayas, however, "Generally speaking, the German population took exception to these trials, especially because the Allies were not similarly bringing their own soldiers to justice."[77]

Irish War of Independence

In the Irish general election of December 1918, the Republican Sinn Féin Party, won a landslide victory. On 21 January 1919, the Sinn Féin MPs, who had refused to take their seats in the House of Commons, met at the official residence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin, convened a nationalist parliament called Dáil Éireann, declared independence from the United Kingdom, and voted to depose George V as King of Ireland.

On the same day, the 3rd Tipperary Brigade of the paramilitary Irish Volunteers ambushed a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) convoy at Soloheadbeg and fatally shot Constables James McDonnell and Patrick O'Connell. The two Constables' deaths were locally regarded as murder and were denounced from local Roman Catholic pulpits. The Dáil, which had not authorized the ambush, was equally outraged by it. The Executive of the Irish Volunteers was also sickened and "the Soloheadbeg Gang" were ostracized throughout the conflict that followed.[82] Even so, the Soloheadbeg ambush is still regarded as the first engagement of the Irish War of Independence.

However, on 31 January, An t-Óglach, the official publication of the Irish Volunteers, instructed all units that the convening of the Dáil "justifies Irish Volunteers in treating the armed forces of the enemy – whether soldiers or policemen – exactly as a National Army would treat the members of an invading army".[83] As a result, the Irish Volunteers increasingly began to be referred to as the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Even so, the Dáil's Prime Minister, Éamon de Valera, advocated nonviolent resistance, such as the social ostracism of policemen. To this end, de Valera actively restrained those who wished to use violence against British security forces. But, in June 1919, de Valera left for a tour of the United States. As a result, Michael Collins, the IRA's Director of Organization, Arms Procurement, and Intelligence, at last received permission to use lethal force against policemen who had intelligence links or who continued to arrest Sinn Féin suspects. These tactics both decimated and demoralized the RIC and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP).[84]

On 7 December 1919, a select committee advised the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Field Marshall Sir John French to infiltrate Sinn Féin with spies and to assassinate "some selected leaders". The committee concluded, "We are inclined to think that the shooting of a few would-be assassins would have an excellent effect. Up to the present, they have escaped with impunity. We think that this should be tried as soon as possible."[85]

Also in hopes of breaking support for the Dáil, Sir Frederick Shaw, British Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill, and Major General Henry Hugh Tudor suggested recruiting World War I veterans into paramilitary units to bolster the disintegrating RIC. David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, who was presiding over a Liberal-Conservative coalition government, agreed. Advertisements were placed in newspapers requesting men ready to face "a rough and dangerous task" and recruiting stations were established in London, Birmingham, Glasgow, and Liverpool.[86]

Veterans who had been commissioned officers were appointed as "Temporary Cadets" of the Auxiliary Division (ADRIC), which received higher pay and better equipment. "Other ranks" became Special Constables of the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force (RICRF) and were dubbed the "Black and Tans" because of their mixture of British Army and RIC uniforms.[87]

Lloyd George initially considered his actions to be an attempt to suppress the guerrilla warfare of the IRA. Eventually, however, a coherent strategy was devised that involved the use of intelligence, propaganda, and armed retaliation. War was never officially declared but a de facto state of war existed after late July 1920. Historian Martin Seedorf says that "between the summers of 1920 and 1921 [there] were systematic reprisals against Irish civilians and their property by British forces retaliating for the IRA's killing of their own men.[88]

Although this conflict is commonly called the Irish War of Independence, the British Government of the time called it "The Troubles."[88]

The Assassination of the Lord Mayor of Cork

On 10 March 1920, the IRA's 1st Cork Brigade shot and severely wounded RIC District Inspector McDonagh near Sawmill Street in Cork City. On 16 March, the Brigade's Officer Commanding, Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork Tomás Mac Curtain, received a letter from the RIC on captured Dáil stationary. The letter read, "Thomas MacCurtain prepare for death. You are doomed."[89]

At 10:40 PM on 19 March 1920, the 1st Cork Brigade fatally shot off duty RIC Constable Joseph Murtagh, who was returning home following a visit to the Palace Theater. Even though Constable Murtagh's assassination had been carried out against the Lord Mayor's orders, RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy ordered immediate retaliation against the commander of the local IRA.

Shortly after 1:00 AM on 20 March 1920, eight RIC personnel with blackened faces arrived at Mac Curtain's residence, which was located above his flour and meal business at 40 Thomas Davis Street. After the Lord Mayor's wife opened the door, one of the policemen demanded that her husband come out. As the Lord Mayor stepped out of the bedroom in his pants and night shirt, he was fatally shot in front of his wife and five children.[90]

Despite his having held senior rank within the IRA, the assassination of Tomás Mac Curtain shocked people throughout Ireland, where "many a person who was far away from the scene of the tragedy felt the awful deed in his own presence."[91]

Retaliation

Following the Lord Mayor's death, the threatening letter was cited by the British Government "to suggest that there was an internal feud among the republicans". Meanwhile, Michael Collins called the assassination a "ghastly affair" and vowed to identify those responsible.[92]

Meanwhile, a coroner's inquest returned a verdict of willful murder against Lloyd George, Lord French, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, and several officials of the RIC. The reading of the verdict was greeted with applause.[91]

Michael Collins later said that the IRA assassinated everyone implicated in the Lord Mayor's death, "one by one, in all parts of the Ireland to which they had been secretly dispersed."[93]

On Sunday 15 August 1920, the IRA's 1st Cork Brigade fatally shot District Inspector Swanzy as he was leaving a Protestant church service in Lisburn, County Antrim. The first shot was fired using Tomás Mac Curtain's revolver. The assassination sparked eight days of anti-Catholic rioting which left 31 people dead and 200 injured in both Lisburn and Belfast.[94]

Rineen Ambush and its aftermath

On 22 September 1920, the IRA ambushed an RIC patrol lorry at Drummin Hill in the townland of Drummin, near the hamlet of Rineen (or Rinneen), County Clare. The attack resulted in the deaths of six policemen. Shortly after, the IRA volunteers were attacked by ten lorry-loads of British Army personnel, who had been sent as reinforcements. However, they held off this attack long enough to flee the scene and sustained only two wounded.[95]

In reprisal for the ambush, the RIC and British military raided three nearby villages, fatally shot five civilians, and burned down 16 residences and shops.[96][97]

Ballyduff and Killorglin

On 21 October 1920, 18-year old medical student and IRA Volunteer Kevin Barry was sentenced to death by a military tribunal in Dublin. On the eve of Barry's execution on 1 November, IRA Headquarters sent out orders for a general attack on British security forces throughout Ireland. An order calling off the attack issued at the last minute failed to reach Patrick Cahill, the IRA's Officer Commanding in County Kerry.[98]

On the night of 31 October 1920, the IRA's 1st Kerry Brigade assassinated RIC Constables George Morgan and Thomas Reidy in Ballyduff, County Kerry. Within hours, British security forces entered the village, burned down the creamery and several local businesses. Teenaged Ballyduff resident John Houlihan was dragged from his parents' house, dragged across the road, bayoneted, shot, and finished off by being bludgeoned with a rifle butt.[99]

On the same night, RICRF Special Constables Herbert Evans and Albert Caseley were fatally shot near Killorglin following a date with two local girls. In retaliation, the Black and Tans burned down Killorglin's Sinn Féin Hall, a nearby garage, the Temperance Association Hall, and the residence of a prominent local Sinn Féin member. Shooting continued until 5:30 AM and local resident Denis O'Sullivan was taken from his house and shot four times in the village square. He never fully recovered and died the following year.[100]

Tralee

On 31 October 1920, RIC Constables Patrick Waters and Ernest Bright were abducted by the IRA's 1st Kerry Brigade in Tralee and later killed. The same night, RIC Constable Daniel McCarthy and naval radio operator Bert Woodward were shot and wounded, also in Tralee. On 1 November, a large force of Black and Tans entered the village. Demanding the safe return of Constables Waters and Bright, they forcibly closed all businesses, and did not let anyone sell or purchase food for nine days. They shot up and burned down several houses and all businesses believed to be connected to IRA activists. Local residents who went outside their homes were verbally abused and fired upon. In the course of the week, Crown security forces shot dead local residents John Conway, Thomas Wall, and Simon O'Connor. By the time businesses were allowed to reopen on November 9, starvation conditions were prevailing in Tralee. The incident caused a major international outcry, angry denunciations in the House of Commons, and front page stories in the British, French, Canadian, and American press.[101]

In an editorial published in the London Daily News, Hugh Martin argued that Tralee was a microcosm of what was happening in Ireland as a whole; the IRA struck, Crown security forces violently retaliated against the entire local population, and support for the IRA was even more firmly cemented throughout the surrounding district.[102]

Bloody Sunday and its aftermath

On the early morning of Sunday, 21 November 1920, IRA leader Michael Collins dispatched his personal assassination squad on a meticulously planned operation at hotels and boarding houses throughout Dublin.[103] In a move that crippled British Intelligence in Ireland,[104] Collins' men fatally shot 13 British spymasters including the majority of the "Cairo Gang".[105]

As the IRA had successfully assassinated less than a third of the British agents intended, Collins and his staff "were disappointed with the result."[106] Even so, the killings caused panic among the surviving agents. Some sought sanctuary in Dublin Castle and many other went into hiding.[107]

Retaliation

That afternoon, a combined force of the RIC, the Dublin Metropolitan Police, the Auxiliary Division, the RICRF, and the British Army stormed Croke Park during a Gaelic football match. Accompanied by an armoured car which remained outside the pitch, security forces were under orders to stop the game and search all males to see if anyone was carrying firearms. Instead, the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans opened fire within the stadium. As the panicking crowd stampeded toward the exits, more than 228 rounds were fired from small arms and 50 from the armoured car. The shooting left 15 people dead (12 men, 1 woman, and 2 children) and 60 wounded, of whom 11 had to be detained in hospital.[108][109]

At a subsequent court of inquiry, paramilitary witnesses alleged that members of the crowd had been armed and had fired first. Even so, the court ruled that the shooting at the stadium was unauthorised, indiscriminate, and unjustifiable. To the outrage of some senior British officers, no further action was taken and the court of inquiry's findings remained unpublished for more than eighty years.[110]

Brigadier General Frank Percy Crozier, who was shortly to resign in protest against Government interference in attempts to hold the shooters involved accountable, publicly quoted a British Army officer who had been present, "It was the most disgraceful show I have ever seen. The Black and Tans fired into the crowd without any provocation whatsoever."[111]

That evening, three captured IRA members held at Dublin Castle, Brigadier Dick McKee, Vice-Brigadier Peadar Clancy, and Volunteer Conor Clune (a nephew of Archbishop Patrick Clune of Perth, Australia), were tortured and summarily shot by the Auxiliary Division's F Company[112][113] officially while attempting to escape.[114]

When the 13 assassinated officers were eulogized in the House of Commons, Irish Parliamentary Party MP Joseph Devlin triggered outrage by raising questions about the deaths at Croke Park. Despite the Chief Secretary for Ireland's grudging insistence that he was "prepared to answer", Devlin was shouted down and physically assaulted by MPs from the Liberal, Conservative, and Labour parties. After the speaker declared the sitting suspended, a number of MPs, in a sign of eroding support for the war in Ireland, went up to Devlin and shook hands with him. Several Conservative MPs, including Viscount Curzon and Sir Harry Brittain, even "engaged in animated discussion" with Devlin. The session resumed after a twenty-minute recess.[115]

The Kilmichael Ambush and its aftermath

On 28 November 1920, Tom Barry, the Officer Commanding of the IRA's 3rd Cork Brigade, and 36 Volunteers ambushed a large lorry convoy at Kilmichael, County Cork. In an engagement lasting 15 minutes, 17 ADRIC Temporary Cadets were killed by gunfire, grenades, and brutal hand-to-hand combat. The British Government later alleged that the dead had been mutilated with axes, which Barry called a blatant fabrication in his memoirs.[116]

Only two members of the Auxiliary Division survived the ambush. Temporary Cadet H.F. Forde was left for dead at the ambush site, was picked up by British forces the following day, and taken to hospital in Cork City. He was awarded £10,000 in compensation. Temporary Cadet Cecil Guthrie, formerly of the Royal Air Force, was severely wounded and fled from the ambush site. After asking for help at a nearby house, Guthrie found that two IRA Volunteers were staying there. Recognized as the killer of local resident Séamus Ó Liatháin, in Ballymakeerahe on 17 October 1920, Temporary Cadet Guthrie was disarmed and shot dead with his own pistol.[117]

On 28 November 1920, Tom Barry, the Officer Commanding of the IRA's 3rd Cork Brigade, and 36 Volunteers ambushed a large lorry convoy at Kilmichael, County Cork. In an engagement lasting 15 minutes, 17 ADRIC Temporary Cadets were killed by gunfire, grenades, and brutal hand-to-hand combat. The British Government later alleged that the dead had been mutilated with axes, which Barry called a blatant fabrication in his memoirs.[116]

Only two members of the Auxiliary Division survived the ambush. Temporary Cadet H.F. Forde was left for dead at the ambush site, was picked up by British forces the following day, and taken to hospital in Cork City. He was awarded £10,000 in compensation. Temporary Cadet Cecil Guthrie, formerly of the Royal Air Force, was severely wounded and fled from the ambush site. After asking for help at a nearby house, Guthrie found that two IRA Volunteers were staying there. Recognized as the killer of local resident Séamus Ó Liatháin, in Ballymakeerahe on 17 October 1920, Temporary Cadet Guthrie was disarmed and shot dead with his own pistol.[117]

In retaliation for the Kilmichael Ambush, British security forces burned numerous houses, shops, and barns in the nearby villages of Kilmichael, Johnstown and Inchageela.[118] On 3 December, three IRA Volunteers were abducted by soldiers of the Essex Regiment in Bandon, beaten, killed, and dumped on the roadside.[118] Meanwhile, in London, barriers were placed on either end of Downing Street to protect the Prime Minister from potential IRA attacks.[119]

The Burning of Cork

.jpg)

On 11 December 1920, IRA commander Seán O'Donoghue received intelligence that two lorries of Temporary Cadets of the Auxiliary Division would be leaving Victoria Barracks in north Cork and that British Army Intelligence Corps Captain James Kelly would be travelling with them.[120] That evening, O'Donoghue and six IRA Volunteers, intending to kill Captain Kelly and as many of those with him as possible, attacked the convoy with gunfire and grenades at Dillon's Cross. During the brief engagement that followed, 12 Temporary Cadets were wounded and one, Spencer Chapman, was killed.[120]

Enraged by an attack so near their headquarters and still wanting revenge for the 18 Temporary Cadets killed at Kilmichael, the Auxiliaries in Victoria Barracks retaliated throughout the following night.[121] Temporary Cadet Charles Schulze, a veteran of the Great War and former Captain in the Dorsetshire Regiment, organized some of the ADRIC's K Company to loot and burn the entire city centre.[122]

Many civilians later reported being physically assaulted, fired upon, robbed at gunpoint, and verbally abused by British security forces. Members of the Cork Fire Brigade later testified that the arsonists had hindered their attempts to fight the blazes by threats, gunfire, and cutting fire hoses.

Unarmed brothers Cornelius and Jeremiah Delaney, who were members of F Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Cork Brigade IRA, were shot dead in their bedroom in the north of the city by unidentified assailants,[123] and a woman died of a heart-attack when Auxiliaries burst into her house.

Over 40 business premises, 300 residential properties, Cork's City Hall, and its Carnegie Library were destroyed. The Auxiliary Division had caused over £3 million worth of damage,[124] left 2,000 civilians unemployed, and left many others homeless.

In a letter to his girlfriend in England, Schulze called the fires, "sweet revenge". In a letter to his mother he wrote: "Many who had witnessed scenes in France and Flanders say that nothing they had experienced was comparable with the punishment meted out in Cork".[122]

On 15 December 1920, two lorry-loads of Auxiliaries were travelling from Dunmanway to Cork for the funeral of Spencer Chapman when they met an elderly priest and a farmer's son helping the resident magistrate fix his car. An Auxiliary got out of his lorry and shot both men dead. A military court of inquiry heard that the Temporary Cadet in question had been a close friend of Chapman and had been "drinking steadily" since his death. He was found guilty of murder, but insane.[125]

For their part in the arson and looting of the city center of Cork, the Auxiliary Division's K Company was disbanded on 31 March 1921.[126]

Reaction in Britain

Arsons, lootings, prisoner abuse, summary executions, and routine reprisals against noncombatants cemented the Irish people's support for the Dáil and caused the British electorate and many of their representatives to demand peace negotiations. Conservative MP Edward Wood, Baron Irwin denounced the use of force and urged the British Government to make an offer to the Dáil "conceived on the most generous lines".[127] Liberal MP Sir John Simon also expressed horror at the tactics being used. Lionel Curtis, writing in the journal The Round Table, wrote: "If the British Commonwealth can only be preserved by such means, it would become a negation of the principle for which it has stood".[128] Senior Church of England bishops, MPs from the Conservative, Liberal, and Labour parties, British Union of Fascists leader Oswald Mosley, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts, the Trades Union Congress, Roman Catholic apologists G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, and many British newspapers grew increasingly critical of the continuing war in Ireland.

In an editorial published during the Tralee Pogrom, The Daily News of London commented, "The vital fact in the tragedy is that while the chief secretary is repeating his stereotyped assurances that things are getting better, it is patent to readers of newspapers the world over that things are daily getting worse. At the moment the supreme need is to withdraw the troops. If the police cannot remain unprotected, let them go too. Ireland could not be worse off without them than with them. There is every reason to believe her state would be incomparably better."[129]

By the summer of 1921, opposition to continuing hostilities had extended to the highest levels of the British Government. King George V had come "to see himself as the father of all his people," and "agonized over the bloodshed and the cruelty".[130]

In July 1921, the New York Times reported that the King had been working behind the scenes to force the Prime Minister to end the war. Most dramatically, the Times alleged that the King, before leaving for Belfast in June to address the new Parliament of Northern Ireland, had angrily asked the Prime Minister, "Are you going to shoot all the people in Ireland?" When Lloyd George replied, "No, Your Majesty," the King responded, "Well, then, you must come to some agreement with them. This thing cannot go on. I cannot have my people killed in this manner."[131] The Prime Minister and the Palace immediately denied being at variance over Ireland and insisted that the conversation had never taken place. However, the diaries of Lloyd George's Secretary, Frances Stevenson record that the Prime Minister summoned the King's Private Secretary, Lord Stamfordham, who admitted to being the source of the leak. Stevenson described Lloyd George as "simply furious."[132]

On 11 July 1921, a ceasefire finally took effect between the British Government and the Dáil. Subsequent negotiations in London led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which guaranteed the independence of the Irish Free State. In response, Indian National Congress leader Mahatma Gandhi said: "It is not fear of losing more lives that has compelled a reluctant offer from England but it is the shame of any further imposition of agony upon a people that loves liberty above everything else".[133]

World War II

Crimes against enemy combatants and civilians

Looting

In violation of the Hague Conventions, British troops conducted small scale looting in Normandy following their liberation.[134] On 21 April 1945, British soldiers randomly selected and burned two cottages in Seedorf, Germany, in reprisal against local civilians who had hidden German soldiers in their cellars.[135] Historian Sean Longden claims that violence against German prisoners and civilians who refused to cooperate with the British army "could be ignored or made light of".[136]

Excessive force against POWs

An MI19 prisoner of war facility, known as the "London Cage", was utilised during and immediately after the war. This facility has been the subject of allegations of torture.[137] The Bad Nenndorf interrogation centre, in occupied Germany, managed by the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre, was the subject of an official inquiry in 1947. It found that there was "mental and physical torture during the interrogations".[138]

Rapes

Rape took place during the British advance towards Germany.[139] During late 1944, with the army based across Belgium and the Netherlands, soldiers were billeted with local families or befriended them. In December 1944, it came to the attention of the authorities that there was a "rise of indecency with children" where abusers had exploited the "atmosphere of trust" that had been created with local families. While the army "attempted to investigate allegations, and some men were convicted, it was an issue that received little publicity."[136] Rape also occurred once British forces had entered Germany.[139] Many rapes were the result of alcohol or post-traumatic stress, but there were also instances of premeditated attacks.[136] For example, on a single day in April 1945, three women in Neustadt am Rübenberge were raped.[139] In the village of Oyle, near Nienburg, two soldiers attempted to coerce two girls into a nearby wood. When they refused, one was grabbed and dragged into the woods. When she began to scream, in according to Longden, "one of the soldiers pulled a gun to silence her. Whether intentionally or in error the gun went off hitting her in the throat and killing her."[136]

Sean Longden highlights that "Some officers failed to treat reports of rape with gravity." He provides the example of a medic, who had a rape reported to him. In cooperation with the Royal Military Police, they were able to track down and apprehend the perpetrators who were then identified by the victim. When the two culprits "were taken before their CO. His response was alarming. He insisted since the men were going on leave no action could be taken and that his word was final."[136]

Bombing of Dresden

The British, with other allied nations (mainly the U.S.) carried out air raids against enemy cities during World War II, including the bombing of the German city of Dresden, which killed around 25,000 people. While "no agreement, treaty, convention or any other instrument governing the protection of the civilian population or civilian property" from aerial attack was adopted before the war,[140] the Hague Conventions did prohibit the bombardment of undefended towns. The city, largely untouched by the war had functioning rail communications to the Eastern front and was an industrial centre. Allied forces inquiry concluded that an air attack on Dresden was militarily justified on the grounds the city was defended.[141]

When asked whether the bombing of Dresden was a war crime, British historian Frederick Taylor replied: "I really don't know. From a practical point of view, rules of war are something of a grey area. It was pretty borderline stuff in terms of the extent of the raid and the amount of force used."[142] Historian Donald Bloxham claims that "the bombing of Dresden on 13–14 February 1945 was a war crime". He further argues that there was a strong prima facie for trying Winston Churchill among others and that there is theoretical case that he could have been found guilty. "This should be a sobering thought. If, however it is also a startling one, this is probably less the result of widespread understanding of the nuance of international law and more because in the popular mind 'war criminal', like 'paedophile' or 'terrorist', has developed into a moral rather than a legal categorisation."[143]

War crimes at sea

Unrestricted submarine warfare

On 4 May 1940, in response to Germany's intensive unrestricted submarine warfare, during the Battle of the Atlantic and its invasion of Denmark and Norway, the Royal Navy conducted its own unrestricted submarine campaign. The Admiralty announced that all vessels in the Skagerrak, were to be sunk on sight without warning. This was contrary to the terms of the Second London Naval Treaty.[144][145]

Shootings of shipwreck survivors

According to Alfred de Zayas, there are numerous documented cases of the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force deliberately firing upon shipwreck survivors.[146]

In July 1941, the submarine HMS Torbay, under Lieutenant Commander Anthony Miers, was based in the Mediterranean where it sank several German ships. On two occasions, once off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt, and the other off the coast of Crete, the crew fired upon shipwrecked German sailors and troops. Miers made no attempt to hide his actions, and reported them in his official logs. He received a strongly worded reprimand from his superiors following the first incident. Mier's actions violated the Hague Convention of 1907, which banned the killing of shipwreck survivors under any circumstances.[147][148]

Attacks against non-combatant ships

On 10 September 1942, the Italian hospital ship Arno was torpedoed and sunk by RAF torpedo bombers north-east of Ras el Tin, near Tobruk. The British claimed that a decoded German radio message intimated that the vessel was carrying supplies to the Axis troops.[149] Arno was the third Italian hospital ship sunk by British aircraft since the loss of the Po in the Adriatic Sea to aerial torpedoes on 14 March 1941 and the bombing of the California off Syracuse on 11 August 1942. Five sea-rescue boats, used to search for missing pilots from both sides of the conflict were also strafed and sunk by RAF planes during the same period.[150]

On 18 November 1944, the German hospital ship Tübingen was sunk by two Beaufighter bombers off Pola, in the Adriatic Sea. The vessel, which had paid a brief visit to the allied-controlled port of Bari to pick up German wounded under the auspices of the Red Cross, was attacked with rockets nine times, despite that the calm sea and the good weather allowed a clear identification of the ship's Red Cross markings. Six crewmembers were killed.[151] American author Alfred M. de Zayas, who evaluated the 266 extant volumes of the Wehrmacht War Crimes Bureau, identifies the sinking of Tübingen and other German hospital ships as war crimes.[152]

Malaya

On 12 December 1948, during the Malayan Emergency, the Batang Kali massacre took place which involved the killing of 24 villagers. The official British position was that these villagers were insurgents attempting to escape, and that detailed investigation into the situation was not possible due to a lack of evidence. Six of the eight British soldiers involved were interviewed under caution by detectives. They corroborated accounts that the villagers were unarmed, were not insurgents nor trying to escape, and had been unlawfully killed on the order of the two sergeants in command. The sergeants denied the allegations. The Government's position was that if anyone is to be held responsible, it should be the Sultan of Selangor.[153][154][155][156]

Decapitation and mutilation of insurgents by British forces were also common as a way to identify dead guerrillas when it was not possible to bring their corpses in from the jungle. A photograph of a Royal Marine commando holding two insurgents’ heads caused a public outcry in April 1952. The Colonial Office privately noted that "there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime".[157][158][159]

As part of the Briggs' Plan devised by British General Sir Harold Briggs, 500,000 people (roughly ten percent of Malaya's population) were eventually removed from the land, had tens of thousands of their homes destroyed, and were interned in 450 guarded fortified camps called "New Villages". The intent of this measure was to inflict collective punishments on villages where people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents and to isolate the population from contact with insurgents. The British also tried to win the hearts of the internees by providing them with education and health services as well as piped water and electricity within the villages. While considered necessary, some of the cases involving the widespread destruction went beyond justification of military necessity. This practice was prohibited by the Geneva Conventions and customary international law which stated that the destruction of property must not happen unless rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.[157][158][160]

Kenya

Treatment of detainees

During an eight-year conflict in Kenya from 1952 to 1960 in which Britain sought to restore order many Kikuyu were relocated. According to David Anderson, the British hanged over 1,090 suspected rebels: far more than the French executed in Algeria during the Algerian War. It was found out that over half of them executed were not rebels at all. Thousands more were killed by British soldiers, who claimed they had "failed to halt" when challenged.[161][162][163] Among the detainees who suffered severe mistreatment was Hussein Onyango Obama, the grandfather of U.S. President Barack Obama. According to his widow, British soldiers forced pins into his fingernails and buttocks and squeezed his testicles between metal rods and two others were castrated.[164]

In June 1957, Eric Griffith-Jones, the attorney general of the British administration in Kenya, wrote to the governor, Sir Evelyn Baring, detailing the way the regime of abuse at the colony's detention camps was being subtly altered. He said that the mistreatment of the detainees is "distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia". Despite this, he said that in order for abuse to remain legal, Mau Mau suspects must be beaten mainly on their upper body, "vulnerable parts of the body should not be struck, particularly the spleen, liver or kidneys", and it was important that "those who administer violence ... should remain collected, balanced and dispassionate". He also reminded the governor that "If we are going to sin," he wrote, "we must sin quietly."[164][165]

Chuka Massacre

The Chuka Massacre, which happened in Chuka, Kenya, was perpetrated by members of the King's African Rifles B Company in June 1953 with 20 unarmed people killed during the Mau Mau uprising. Members of the 5th KAR B Company entered the Chuka area on 13 June 1953, to flush out rebels suspected of hiding in the nearby forests. Over the next few days, the regiment had captured and executed 20 people suspected of being Mau Mau fighters for unknown reasons. It is found out that most of the people executed were actually belonged to the Kikuyu Home Guard - a loyalist militia recruited by the British to fight an increasingly powerful and audacious guerrilla enemy. In an atmosphere of atrocity and reprisal, the matter was swept under the carpet and nobody ever stood trial for the massacre.[166]

Hola Massacre

The Hola massacre was an incident at a detention camp in Hola, Kenya. By January 1959 the camp had a population of 506 detainees of whom 127 were held in a secluded "closed camp". This more remote camp near Garissa, eastern Kenya, was reserved for the most uncooperative of the detainees. They often refused, even when threats of force were made, to join in the colonial "rehabilitation process" or perform manual labour or obey colonial orders. The camp commandant outlined a plan that would force 88 of the detainees to bend to work. On 3 March 1959, the camp commandant put this plan into action – as a result, 11 detainees were clubbed to death by guards.[167] All of the surviving detainees sustained serious permanent injuries.[168] The British government accepts that the colonial administration tortured detainees, but denies liability.[169]

Iraq War

There were a number of cases where British soldiers opened fire and killed Iraqi civilians in circumstances where there was apparently no imminent threat of death or serious injury to themselves or others. Many of them resorted to lethal force even though the use of such force did not appear to be justified by military necessity in order to protect life.[170][171][172] Many Iraqi civilians also died or were seriously injured from brutal mistreatment while under British custody.[173][174] In one case, following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, a video showed British soldiers brutally beating an Iraqi civilian after the killing of six Royal Military Policemen, known as Red Caps, by an Iraqi mob.[175]

In May 2003, Saeed Shabram and his cousin, Menem Akaili, were thrown into the river near Basra after being detained by British troops. Akaili survived but Shabram did not as he drowned in the river. Akaili said that he and Shabram were approached by a British patrol and led at gunpoint down to a jetty before being forced into the river. The punishment was known as "wetting" and said to have been inflicted on local youths suspected of looting. "Wetting was supposed to humiliate those suspected of being petty criminals," said Sapna Malik, the family's lawyer at Leigh Day and Co. "Although the MoD denies that there was a policy of wetting to deal with suspected looters around the time of this incident, evidence we have seen suggests otherwise. The tactics employed by the MoD appeared to include throwing or placing suspected looters into either of Basra's two main waterways." Iraqi bystanders dragged Akaili out of the water but his cousin disappeared. Shabram's body was later recovered by a diver hired by his father, Radhi Shabram. Shabram's mother waited on the river bank for four hours, screaming and crying, while the diver searched the river. "When Saeed's corpse was finally pulled from the river, Radhi describes how it was bloated and covered with marks and bruises," said Leigh Day. Though the MOD paid compensation to Saeed Shabram's family, none of the British soldiers were charged for his death.[176]

Ahmed Jabbar Kareem Ali, aged 15, was on his way to work with his brother on 8 May 2003, when British soldiers assaulted him. The four British soldiers beat him then forced him into a canal at gunpoint to "teach him a lesson" for suspected looting (which wasn't proven to be true). Weakened from the beating Ali received from the soldiers, he floundered. He was dead when he was pulled from the river. Four British soldiers who were involved in the death of an Iraqi teenager were acquitted of manslaughter.[177][178]

Corporal Donald Payne (born 9 September 1970)[179] is a former soldier of the Queen's Lancashire Regiment of the British Army who became the first member of the British armed forces to be convicted of a war crime under the provisions of the International Criminal Court Act 2001 for the death of Baha Mousa when he pleaded guilty on 19 September 2006 to a charge of inhumane treatment.[180][181] He was jailed for one year and dismissed from the army as a result of his actions.[182]

On 1 January 2004, Ghanem Kadhem Kati, an unarmed young man, was shot twice in the back by a British soldier at the door to his home. Troops had arrived at the scene after hearing shooting, which neighbours said came from a wedding party. Investigators from the Royal Military Police exhumed the teenager's body six weeks later but have yet to offer compensation or announce any conclusion to the inquiry.[170]

In May 2004, a British soldier identified as M004 allegedly mistreated captured, unarmed prisoners of war during a 'tactical questioning' in Camp Abu Naji.[183]

In February 2006, a video showing a group of British soldiers beating several Iraqi teenagers was posted on the internet, and shortly thereafter, on the main television networks around the world. The video took place in April 2004 and was taken from an upper storey of a building in the southern Iraqi town of Al-Amarah, shows many Iraqis outside a coalition compound. Following an altercation in which members of the crowd tossed rocks and reportedly an improvised grenade at the soldiers, the British soldiers rushed the crowd. The troopers brought some Iraqi teenagers into the compound and proceeded to beat them. The video includes a voiceover in a British accent by the cameraman, taunting the beaten teenagers. The individual recording could be heard saying:

- Oh, yes! Oh Yes! Now you gonna get it. You little kids. You little motherfucking bitch!, you little motherfucking bitch.[184]

The event was broadcast in mainstream media, resulting in the British government and military condemning the event. The incident became especially worrisome for British soldiers, who had enjoyed a more favourable position than American soldiers in the region. Concerns were voiced to the media about the safety of soldiers in the country after the incident. The tape incurred criticism, albeit relatively muted, from Iraq, and media found people prepared to speak out. The Royal Military Police conducted an investigation into the event, and the prosecuting authorities determined that there was insufficient case to justify court martial proceedings.[174][185]

Afghan War

In September 2013,[186] Royal Marines Sergeant Alexander Blackman, formerly of Taunton, Somerset,[187] was convicted at court martial of having murdered an unarmed, wounded Taliban insurgent in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. On 6 December 2013, Sgt. Blackman received a sentence of life imprisonment with a minimum of ten years before being eligible for parole. He was also dismissed with disgrace from the Royal Marines.[188][189]

In popular culture

Films

- Breaker Morant (1980) by Bruce Beresford. A film focussing on one of the first prosecutions for war crimes in British military history - the 1902 court martial of Lieutenants Harry Harbord Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton. Set at the end of the Second Anglo-Boer War, Breaker Morant unfolds during the trial; the acts for which the defendants stand accused are shown in flashbacks. The three defendants are accused of the revenge killing of a Boer prisoner and the summary execution by firing squad of six other Boers after they had surrendered and been disarmed. Furthermore, Lieuts. Morant and Handcock stand accused of murdering the Rev. C.A.D. Heese of the Berlin Missionary Society. Like the defence lawyers at the Nuremberg Trials, the trio's counsel vainly argues that his clients only followed orders. In a 1999 interview, director Bruce Beresford explained, "The film never pretended for a moment that they weren't guilty." He had made the film, he added, to explore how war crimes can be "committed by people who appear to be quite normal." Beresford also lamented that his film still causes many to view Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton as "poor Australians framed by the Brits."[190]

- Michael Collins by Neil Jordan. A biopic set between during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War, Michael Collins depicts British security forces' retaliation for the IRA's massacre of British secret service agents on Bloody Sunday. The film is incorrect, however, in its depiction of the armoured car entering the stadium during the Croke Park massacre.