Camden, New Jersey

| Camden, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| City of Camden | |

|

Camden City Hall | |

| Motto: In a Dream, I Saw a City Invincible[1] | |

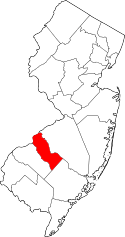

Map of Camden in Camden County. Inset: Location of Camden County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. | |

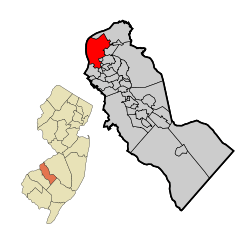

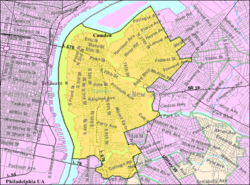

Census Bureau map of Camden, New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 39°56′24″N 75°06′18″W / 39.94°N 75.105°WCoordinates: 39°56′24″N 75°06′18″W / 39.94°N 75.105°W[2][3] | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| County | Camden |

| Settled | 1626 |

| Incorporated | February 13, 1828 |

| Named for | Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden |

| Government[4] | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Dana Redd (D, term ends December 31, 2017)[5][6] |

| • Administrator | Christine T. J. Tucker[7] |

| • Clerk | Luis Pastoriza[8] |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 10.341 sq mi (26.784 km2) |

| • Land | 8.921 sq mi (23.106 km2) |

| • Water | 1.420 sq mi (3.677 km2) 13.73% |

| Area rank |

208th of 566 in state 7th of 37 in county[2] |

| Elevation[9] | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population (2010 Census)[10][11][12][13] | |

| • Total | 77,344 |

| • Estimate (2015)[14] | 76,119 |

| • Rank |

12th of 566 in state 1st of 37 in county[15] |

| • Density | 8,669.6/sq mi (3,347.4/km2) |

| • Density rank |

42nd of 566 in state 2nd of 37 in county[15] |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern (EDT) (UTC-4) |

| ZIP codes | 08100-08105[16][17] |

| Area code(s) | 856[18] |

| FIPS code | 3400710000[2][19][20] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885177[2][21] |

| Website |

www |

Camden is a city in Camden County, New Jersey, United States. The county seat,[22][23] it is across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the 2010 United States Census, the city had a population of 77,344,[10][12][13] representing a decline of 2,560 (3.2%) from the 79,904 residents enumerated during the 2000 Census, which had in turn declined by 7,588 (8.7%) from the 87,492 counted in the 1990 Census.[24] Camden ranked as the 12th-most populous municipality in the state in 2010 after having been ranked 10th in 2000.[11]

Camden was incorporated as a city on February 13, 1828, from portions of the now-defunct Newton Township, while the area was still part of Gloucester County. On March 13, 1844, Camden became part of the newly formed Camden County.[25] The city derives its name from Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden.[26][27]

Three of Camden's mayors have been jailed for corruption, the most recent being Milton Milan in 2000.[28] From 2005 to 2012, the school system and police department were operated by the state of New Jersey.[29][30][31][32] 40% of residents are below the national poverty line.[33]

Camden had the highest crime rate in the United States in 2012, with 2,566 violent crimes for every 100,000 people,[34] 6.6 times higher than the national average of 387 violent crimes per 100,000 citizens.[35]

History

Early history

In 1626 Fort Nassau was established by the Dutch West India Company in the area that is now knows as Camden, New Jersey. Europeans settled along the Delaware River, attempting to control the local fur trade. Throughout the 17th century more Europeans arrived in the area, developing it and making improvements. The growth of the colony was the result of Philadelphia, a Quaker colony directly across from Camden along the Delaware River. Ferry systems were established to facilitate trade between Fort Nassau and Philadelphia. The ferry system made stops along along the east side of the Delaware River directly resulted in the area which would become Camden in 1830.[36]

19th century

For over 150 years, Camden served as a secondary economic and transportation hub for the Philadelphia area. But that status began to change in the early 19th century. One of the U.S.'s first railroads, the Camden and Amboy Railroad, was chartered in Camden in 1830. The Camden and Amboy Railroad allowed travelers to travel between New York City and Philadelphia via ferry terminals in South Amboy, New Jersey and Camden. The railroad terminated on the Camden waterfront, and passengers were ferried across the Delaware River to their final Philadelphia destination. The Camden and Amboy Railroad opened in 1834 and helped to spur an increase in population and commerce in Camden.[37]

Horse ferries, or team boats served Camden in the early 1800s. They stopped for an hour at lunch time to feed the horses.[38] The Ridgeway was a double team boat, propelled by nine horses walking around a circle. She ran from the foot of Cooper Street. There was also a team boat named the Washington; she ran from Market Street, Camden, to Market Street, Philadelphia. Other team boats followed in succession, namely the Phoenix, Constitution, Moses Lancaster, and Independence.[39] The Cooper's Ferry Daybook, 1819–1824, documenting Camden's Point Pleasant Teamboat, survives to this day.[40]

Originally a suburban town with ferry service to Philadelphia, Camden evolved into its own city. Until 1844 Camden was a part of Gloucester County. In 1840 the city's population had reached 3,371 and Camden appealed to state legislature, which resulted in the creation of Camden County in 1844.[36] Camden quickly became an industrialized city in the later half of the nineteenth century. In 1860 Census takers recorded eighty factories in the city and the number of factories grew to 125 by 1870.[36] Camden began to industrialize in 1891 when Joseph Campbell incorporated his business Campbell's Soup. Through the Civil War era Camden gained a large immigrant population which formed the base of it's industrial workforce.[41] Between 1870 and 1920 Camden's population grew by 96,000 people due to the large influx of immigrants.[36] Like other industrial towns, Camden prospered during strong periods of manufacturing demand and faced distress during periods of economic dislocation.[42]

First half of the 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century Camden became an industrialized city. At the height of Camden's industrialization, 12,000 workers were employed at RCA,[43] while another 30,000 worked at New York Shipbuilding.[44] RCA had 23 out of 25 of its factories inside Camden. Campbell Soup was also a major employer.[45] In addition to major corporations Camden housed many small manufacturing companies as well as commercial offices.[41]

From 1899 to 1967, Camden was the home of New York Shipbuilding Corporation, which at its World War II peak was the largest and most productive shipyard in the world.[46] Notable naval vessels built at New York Ship include the ill-fated cruiser USS Indianapolis and the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk. In 1962, the first commercial nuclear-powered ship, the NS Savannah, was launched in Camden.[47] The Fairview Village section of Camden (initially Yorkship Village) is a planned European-style garden village that was built by the Federal government during World War I to house New York Shipbuilding Corporation workers.[48]

From 1901 through 1929, Camden was headquarters of the Victor Talking Machine Company, and thereafter to its successor RCA Victor, the world's largest manufacturer of phonographs and phonograph records for the first two-thirds of the 20th century.[49] In Victor contained some of the first commercial recording studios in the United States, where Enrico Caruso, among others, recorded. General Electric reacquired RCA and the Camden factory in 1986.[50]

During the 1930s Camden faced a decline in economic prosperity due to the Great Depression. By the mid-1930s the city had to pay its workers in scrip because they could not pay them in currency.[41] Camden's industrial foundation kept the city from going bankrupt. Major corporations such as Campbell's soup, New York Shipbuilding Corporation and RCA Victor employed close to 25,000 people through the depression years.[41] New companies were also being created during this time. On June 6, 1933, the city hosted the first drive-in movie.[51][52]

Camden's ethnic demographic changed drastically at the beginning of the twentieth century. German, British, and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the city at the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century. By 1920 Italian and Eastern European immigrants had become the majority of the population.[36] The different ethnic groups began to form segregated communities within the city formed around religious organizations. Communities formed around figures such as Tony Mecca from the Italian neighborhood, Mario Rodriguez from the Puerto Rican neighborhood, and Ulysses Wiggins from the African American neighborhood.[41]

Second half of the 20th century

After close to 50 years of economic and industrial growth, the city of Camden faced a period of economic stagnation and deindustrialization: after reaching a peak of 43,267 manufacturing jobs in 1950, there was an almost continuous decline to a new low of 10,200 manufacturing jobs in the city by 1982. With this industrial decline came a plummet in population: in 1950 there were 124,555 residents, compared to just 84,910 in 1980.[41] Alongside these declines, civil unrest and criminal activity rose in the city. From 1981 to 1990, mayor Randy Primas fought to renew the city economically. Ultimately Primas had not secured Camden's economic future as his successor, mayor Miltan Milan, declared bankruptcy for the city in July 1999.

Civil unrest and crime

- On September 6, 1949, mass murderer Howard Unruh went on a killing spree in his Camden neighborhood killing thirteen people. Unruh, who was convicted and subsequently confined to a state psychiatric facility, died on October 19, 2009.[53]

- Camden experienced a fatal anti-police riot in September 1969.[54][55] Two years later, public disorder returned with widespread riots in August 1971, following the death of a Puerto Rican motorist at the hands of white police officers. When the officers were not charged, Hispanic residents took to the streets and called for the suspension of those involved. The officers were ultimately charged, but remained on the job and tensions soon flared. On the night of August 19, 1971, riots erupted, and sections of downtown were looted and torched over the next three days.[56][57] Fifteen major fires were set before order was restored, and ninety people were injured. City officials ended up suspending the officers responsible for the death of the motorist, but they were later acquitted by a jury.[58][59]

- The Camden 28 were a group of anti-Vietnam War activists who, in 1971, planned and executed a raid on the Camden draft board, resulting in a high-profile trial against the activists that was seen by many as a referendum on the Vietnam War in which 17 of the defendants were acquitted by a jury even though they admitted having participated in the break-in.[60]

- In 1996, Governor of New Jersey Christine Todd Whitman frisked Sherron Rolax, a 16-year-old African-American youth, an event which was captured in an infamous photograph. Rolax alleged his civil rights were violated and sued the state of New Jersey.[61]

Attempts at renewal

In 1981, Randy Primas was elected mayor of Camden, but was unfortunately "haunted by the overpowering legacy of financial disinvestment".[62] Following his election, the state of New Jersey closed the $4.6 million deficit that Primas had inherited, but also decided that Primas should lose budgetary control until he began providing the state with monthly financial statements, among other requirements.[62] When he regained control, Primas had limited options regarding how to close the deficit, and so in an attempt to renew Camden, Primas campaigned for the city to adopt two different nuisance industries: a prison and a trash-to-steam incinerator. While these two industries would provide some financial security for the city, the proposals for them did not go over well with residents, who overwhelmingly opposed both the prison and the incinerator.

While the proposed prison, which was to be located on the North Camden waterfront, would generate $3.4 million for Camden, Primas faced extreme disapproval from residents. Many believed that a prison in the neighborhood would negatively effect North Camden's "already precaarious economic situation". Primas, however, was wholly concerned with the economic benefits: he told The New York Times, "The prison was a purely economic decision on my part."[63] Eventually, on August 12, 1985, the Riverfront State Prison opened its doors, despite the objections of residents.

The trash-to-steam incinerator was another proposed industry, also objected to by Camden residents. Once again, Primas "...was motivated by fiscal more than social concerns," and he faced heavy opposition from Concerned Citizens of North Camden (CCNC) and from Michael Doyle, who was so opposed to the plant that he appeared on CBS's 60 Minutes, saying "Camden has the biggest concentration of people in all the county, and yet there is where they're going to send in this sewage... ...everytime you flush, you send to Camden, to Camden, to Camden".[64] Despite this opposition, which eventually culminated in protests, "the county proceeded to present the city of Camden with a check for $1 million in March 1989, in exchange for the eighteen acres of city-owned land where the new facility was to be built... ...The $112 million plant finally fired up for the first time in March 1991".[65]

Other notable events

Despite the declines in industry and population, other changes to the city took place during this period:

- In 1950, Rutgers University absorbed the former College of South Jersey to create Rutgers University–Camden.[66]

- In 1992, the state of New Jersey under the Florio administration made an agreement with GE to ensure that GE would not close the Camden site. The state of New Jersey would build a new high-tech facility on the site of the old Campbell Soup Company factory and trade these new buildings to GE for the existing old RCA Victor buildings. Later, the new high tech buildings would be sold to Martin Marietta. In 1994, Martin Marietta merged with Lockheed to become Lockheed Martin. In 1997, Lockheed Martin divested the Camden Plant as part of the birth of L-3 Communications.[67]

- In 1999, Camden was selected as the location for the USS New Jersey (BB-62).[68] That ship remains in Camden.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 10.341 square miles (26.784 km2), including 8.921 square miles (23.106 km2) of land and 1.420 square miles (3.677 km2) of water (13.73%).[2][3]

Camden borders Collingswood, Gloucester City, Haddon Township, Pennsauken Township and Woodlynne in Camden County, as well as Philadelphia across the Delaware River in Pennsylvania.[69] Just offshore of Camden is Pettys Island, which is part of Pennsauken Township. The Cooper River (popular for boating) flows through Camden, and Newton Creek forms Camden's southern boundary with Gloucester City.

Camden contains the United States' first federally funded planned community for working class residents, Yorkship Village (now called Fairview).[70] The village was designed by Electus Darwin Litchfield, who was influenced by the "garden city" developments popular in England at the time.[71]

Neighborhoods

Camden has more than 20 generally recognized neighborhoods:[72][73][74][75]

- Ablett Village

- Bergen Square

- Beideman

- Broadway

- Centerville

- Center City/Downtown Camden/Central Business District

- Central Waterfront

- Cooper

- Cooper Grant

- Cooper Point

- Cramer Hill

- Dudley

- East Camden

- Fairview

- Gateway

- Kaighn Point

- Lanning Square

- Liberty Park

- Marlton

- Morgan Village

- North Camden

- Parkside

- Pavonia

- Pyne Point

- Rosedale

- South Camden

- Stockton

- Waterfront South

- Whitman Park

- Yorkship

Port

On the Delaware River, with access to the Atlantic Ocean, the Port of Camden handles break bulk and bulk cargo. The port consists of two terminals: the Beckett Street Terminal and the Broadway Terminal. The port receives hundreds of ships moving international and domestic cargo annually.[76]

In 2005, the Port of Camden (South Jersey Port Corporation) was subject to an unresolved criminal investigation[77] and a state audit.[78] Some activities in the port are under the jurisdiction of the Delaware River Port Authority.

Climate

Camden has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Koeppen climate classification).

| Climate data for Camden, New Jersey | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

65 (18) |

74 (23) |

82 (28) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

67 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

65.083 (18.379) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

52 (11) |

61 (16) |

67 (19) |

65 (18) |

58 (14) |

46 (8) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

45.083 (7.268) |

Source: <Weather.com >Camden, NJ (08102). Weather.com. 2016 https://weather.com/weather/monthly/l/Camden+NJ+08102:4:US. Retrieved 14 September 2016. Missing or empty |title= (help) | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 3,371 | — | |

| 1850 | 9,479 | 181.2% | |

| 1860 | 14,358 | 51.5% | |

| 1870 | 20,045 | 39.6% | |

| 1880 | 41,659 | 107.8% | |

| 1890 | 58,313 | 40.0% | |

| 1900 | 75,935 | 30.2% | |

| 1910 | 94,538 | 24.5% | |

| 1920 | 116,309 | 23.0% | |

| 1930 | 118,700 | 2.1% | |

| 1940 | 117,536 | −1.0% | |

| 1950 | 124,555 | 6.0% | |

| 1960 | 117,159 | −5.9% | |

| 1970 | 102,551 | −12.5% | |

| 1980 | 84,910 | −17.2% | |

| 1990 | 87,492 | 3.0% | |

| 2000 | 79,318 | −9.3% | |

| 2010 | 77,344 | −2.5% | |

| Est. 2015 | 76,119 | [14][79] | −1.6% |

| Population sources: 1840–2000[80][81] 1840–1920[82] 1840[83] 1850–1870[84] 1850[85] 1870[86] 1880–1890[87] 1890–1910[88] 1840–1930[89] 1930–1990[90] 2000[91][92][93] 2010[10][11][12][13] | |||

| Demographic profile | 1950[94] | 1970[94] | 1990[94] | 2010[10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 85.9% | 59.8% | 19.0% | 17.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic | N/A | 52.9% | 14.4% | 4.9% |

| Black or African American | 14.0% | 39.1% | 56.4% | 48.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | N/A | 7.6% | 31.2% | 47.0% |

| Asian | — | 0.2% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

As of 2006, 52% of the city's residents lived in poverty, one of the highest rates in the nation.[95] The city had a median household income of $18,007, the lowest of all U.S. communities with populations of more than 65,000 residents, making it America's poorest city.[96] A group of poor Camden residents were the subject of a 20/20 special on poverty in America broadcast on January 26, 2007, in which Diane Sawyer profiled the lives of three young children growing up in Camden.[97] A follow-up was shown on November 9, 2007.[98]

In 2011, Camden's unemployment rate was 19.6%, compared with 10.6% in Camden County as a whole.[99] As of 2009, the unemployment rate in Camden was 19.2%, compared to the 10% overall unemployment rate for Burlington, Camden and Gloucester counties and a rate of 8.4% in Philadelphia and the four surrounding counties in Southeastern Pennsylvania.[100]

2010 Census

At the 2010 United States Census, there were 77,344 people, 24,475 households, and 16,912 families residing in the city. The population density was 8,669.6 per square mile (3,347.4/km2). There were 28,358 housing units at an average density of 3,178.7 per square mile (1,227.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 17.59% (13,602) White, 48.07% (37,180) Black or African American, 0.76% (588) Native American, 2.12% (1,637) Asian, 0.06% (48) Pacific Islander, 27.57% (21,323) from other races, and 3.83% (2,966) from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 47.04% (36,379) of the population.[10] The Hispanic population of 36,379 was the tenth-highest of any municipality in New Jersey and the proportion of 47.0% was the state's 16th-highest percentage.[101][102] The Puerto Rican population was 30.7%.[10]

There were 24,475 households, of which 37.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 22.3% were married couples living together, 37.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.9% were non-families. 24.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.02 and the average family size was 3.56.[10]

In the city, 31.0% of the population were under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 28.0% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28.5 years. For every 100 females there were 94.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.0 males.[10]

The city of Camden was 47% Hispanic of any race, 44% non-Hispanic black, 6% non-Hispanic white, and 3% other. Camden is predominately populated by African Americans and Puerto Ricans.[10]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $27,027 (with a margin of error of +/- $912) and the median family income was $29,118 (+/- $1,296). Males had a median income of $27,987 (+/- $1,840) versus $26,624 (+/- $1,155) for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,807 (+/- $429). About 33.5% of families and 36.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.3% of those under age 18 and 26.2% of those age 65 or over.[103]

2000 Census

As of the 2000 United States Census[19] there were 79,904 people, 24,177 households, and 17,431 families residing in the city. The population density was 9,057.0 people per square mile (3,497.9/km²). There were 29,769 housing units at an average density of 3,374.3 units per square mile (1,303.2/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 16.84% White, 53.35% African American, 0.54% Native American, 2.45% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 22.83% from other races, and 3.92% from two or more races. 38.82% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[91][92][93]

There were 24,177 households out of which 42.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 26.1% were married couples living together, 37.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.9% were non-families. 22.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.52 and the average family size was 4.00.[91][92][93]

In the city, the population is quite young with 34.6% under the age of 18, 12.0% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 16.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females there were 94.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.0 males.[91][92][93]

The median income for a household in the city was $23,421, and the median income for a family was $24,612. Males had a median income of $25,624 versus $21,411 for females. The per capita income for the city is $9,815. 35.5% of the population and 32.8% of families were below the poverty line. 45.5% of those under the age of 18 and 23.8% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[91][92][93]

In the 2000 Census, 30.85% of Camden residents identified themselves as being of Puerto Rican heritage. This was the third-highest proportion of Puerto Ricans in a municipality on the United States mainland, behind only Holyoke, Massachusetts and Hartford, Connecticut, for all communities in which 1,000 or more people listed an ancestry group.[104]

Culture

Camden's role as an industrial city gave rise to distinct neighborhoods and cultural groups that have effected the growth and decline of the city over the course of the 20th century. Camden is also home to historic landmarks detailing its rich history in literature, music, social work, and industry such as the Walt Whitman House,[183] the Walt Whitman Cultural Arts Center, the Rutgers–Camden Center For The Arts and the Camden Children's Garden.

Camden's cultural history has been greatly affected by both its economic and social position over the years. From 1950 to 1970 industry plummeted, losing close to 20,000 jobs for Camden residents.[105] This mass unemployment as well as social pressure from neighboring townships caused an exodus of citizens, mostly white. This gap was filled by new African American and Latino citizens and led to a restructuring of Camden's communities. The mass number of White citizen who left to neighboring towns such as Collingswood or Cherry Hill, leaving both new and old African American and Latino citizens to begin to rebuild their community. To help this rebuilding process, numerous non-for-profit organizations such as Hopeworks or the Neighborhood Center have been formed to facilitate Camden's movement into the 21st century.[41]

Hispanic and Latino Culture

One of the longest standing traditions in Camden's Hispanic community is the San Juan Bautista Parade, a celebration of St. John the Baptist, conducted annually starting in 1957. The parade began in 1957 when a group of parishioners from Our Lady of Mount Carmel marched with the church founder Father Leonardo Carrieri. This march was originally a way for the parishioners to recognize and show their Puerto Rican Heritage, and eventually became the modern day San Juan Bautista Parade. Since its conception, the parade has grown into the Parada San Juan Bautista, Inc, a non-for-profit organization dedicated to maintaining the community presence of Camden's Hispanic and Latino members. Some of the work that the Parada San Juan Bautista, Inc has done include a month long event for the parade with a community commemorative mass and a coronation pageant. The organization also awards up to $360,000 in scholarships to high school students of Puerto Rican descent

Waterfront

Camden has two generally recognized neighborhoods located on the Delaware River waterfront, Central and South. The Waterfront South was founded in 1851 by the Kaighns Point Land Company. During World War Two, Waterfront South housed many of the industrial workers for the New York Shipbuilding Company. Currently, the Waterfront is home to many historical buildings and cultural icons. The Waterfront South neighborhood is considered a federal and state historic area due to its history and culturally significant buildings, such as the Sacred Heart Church, and the South Camden Trust Company[106] The Central Waterfront is located adjacent to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and is home to the Nipper Building (also known as The Victor), the Adventure Aquarium, and Battleship New Jersey, a museum ship located at the Home Port Alliance.

Economy

About 45% of employment in Camden is in the "eds and meds" sector, providing educational and medical institutions.[107]

Largest employers

- Campbell Soup Company

- Cooper University Hospital

- Delaware River Port Authority

- L-3 Communications, formerly Lockheed Martin

- Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center

- Rutgers–Camden

- State of New Jersey

- New Jersey Judiciary

- Susquehanna Bank

- UrbanPromise Ministry (largest private employer of teenagers)

Urban enterprise zone

Portions of Camden are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3½% sales tax rate (versus the 7% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[108]

Redevelopment

Campbell Soup Company has decided to go forward with a scaled down redevelopment of the area around its corporate headquarters in Camden, including an expanded corporate headquarters.[109] In June 2012, Campbell Soup Company acquired the 4-acre (1.6 ha) site of the vacant Sears building located near its corporate offices, where the company plans to construct the Gateway Office Park, and razed the Sears building after receiving approval from the city government and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.[110]

In 2013, Cherokee Investment Partners had a plan to redevelop north Camden with 5,000 new homes and a shopping center on 450 acres (1.8 km2). Cherokee dropped their plans in the face of local opposition and the slumping real estate market.[111][112][113]

In 2014, Lockheed Martin, Holt Logistics, Subaru of America, WebiMax, Holtec International and the Philadelphia 76ers announced plans to open facilities in the city.[114][115][116] [117][118] They are among several companies receiving New Jersey Economic Development Authority (EDA) tax incentives to relocate jobs in the city.[119][120]

Government

Camden has historically been a stronghold of the Democratic Party. Voter turnout is very low; approximately 19% of Camden's voting age population participated in the 2005 gubernatorial election.[121]

Local government

Since July 1, 1961, the city has operated within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under a Mayor-Council form of government.[4] Under this form of government, the City Council consisted of seven Council members originally all elected at-large. In 1994, the City divided the city into four council districts, instead of electing the entire Council at-large, with a single council member elected from each of the four districts. In 1995, the elections were changed from a partisan vote to a non-partisan system.[122]

As of 2016, the Mayor of Camden is Democrat Dana Redd, who was re-elected to a second term in office in 2013 and whose current term ends December 31, 2017.[5] Members of the City Council are Council President Francisco "Frank" Moran (2015; Ward 3), Vice President Curtis Jenkins (D, 2017; at large), Dana M. Burley (2015; Ward 1), Brian K. Coleman (2015; Ward 2), Angel Fuentes (D, 2017; at large - appointed to serve an unexpired term), Luis A. Lopez (2015; Ward 4) and Marilyn Torres (D, 2017; at large).[123][124][125][126]

Angel Fuentes was appointed to the at-large term ending in December 2017 that was vacated by Arthur Barclay when he took office in the New Jersey General Assembly in January 2016.

Mayor Milton Milan was jailed for his connections to organized crime. On June 15, 2001, he was sentenced to serve seven years in prison on 14 counts of corruption, including accepting mob payoffs and concealing a $65,000 loan from a drug kingpin.[28]

Federal, state and county representation

Camden is located in the 1st Congressional District[127] and is part of New Jersey's 5th state legislative district.[12][128][129]

New Jersey's First Congressional District is represented by Donald Norcross (D, Camden).[130] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Cory Booker (D, Newark, term ends 2021)[131] and Bob Menendez (D, Paramus, 2019).[132][133]

For the 2016–2017 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 5th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Nilsa Cruz-Perez (D, Barrington) and in the General Assembly by Arthur Barclay (D, Camden) and Patricia Egan Jones (D, Barrington).[134] The Governor of New Jersey is Chris Christie (R, Mendham Township).[135] The Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey is Kim Guadagno (R, Monmouth Beach).[136]

Camden County is governed by a Board of Chosen Freeholders, whose seven members chosen at-large in partisan elections to three-year terms office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election each year.[137] As of 2015, Camden County's Freeholders are Freeholder Director Louis Cappelli, Jr. (Collingswood, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2017; term as director ends 2015),[138] Freeholder Deputy Director Edward T. McDonnell (Pennsauken Township, term as freeholder ends 2016; term as deputy director ends 2015),[139] Michelle Gentek (Gloucester Township, 2015),[140] Ian K. Leonard (Camden, 2015),[141] Jeffrey L. Nash (Cherry Hill, 2015),[142] Carmen Rodriguez (Merchantville, 2016)[143] and Jonathan L. Young, Sr. (Berlin Township, November 2015; serving the unexpired term of Scot McCray ending in 2017)[144][145][146]

Camden County's constitutional officers, all elected directly by voters, are County clerk Joseph Ripa,[147] Sheriff Charles H. Billingham,[148] and Surrogate Patricia Egan Jones.[146][149] The Camden County Prosecutor Mary Eva Colalillo was appointed by the Governor of New Jersey with the advice and consent of the New Jersey Senate (the upper house of the New Jersey Legislature).[150]

Political corruption

Three Camden mayors have been jailed for corruption: Angelo Errichetti, Arnold Webster, and Milton Milan.[151]

In 1981, Errichetti was convicted with three other individuals for accepting a $50,000 bribe from FBI undercover agents in exchange for helping a non-existent Arab sheikh enter the United States.[152] The FBI scheme was part of the Abscam operation. The 2013 film American Hustle is a fictionalized portrayal of this scheme.[153]

In 1999, Webster, who was previously the superintendent of Camden City Public Schools, pleaded guilty to illegally paying himself $20,000 in school district funds after he became mayor.[154]

In 2000, Milan was sentenced to more than six years in federal prison for accepting payoffs from associates of Philadelphia organized crime boss Ralph Natale,[155] soliciting bribes and free home renovations from city vendors, skimming money from a political action committee, and laundering drug money.[156]

The Courier-Post dubbed former State Senator Wayne R. Bryant, who represented the state's 5th Legislative District from 1995 to 2008, the "king of double dipping" for accepting no-show jobs in return for political benefits.[157] In 2009, Bryant was sentenced to four years in federal prison for funneling $10.5 million to the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) in exchange for a no-show job and accepting fraudulent jobs to inflate his state pension and was assessed a fine of $25,000 and restitution to UMDNJ in excess of $110,000.[158] In 2010, Bryant was charged with an additional 22 criminal counts of bribery and fraud, for taking $192,000 in false legal fees in exchange for backing redevelopment projects in Camden, Pennsauken Township and the New Jersey Meadowlands between 2004 and 2006.[159]

Politics

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 43,893 registered voters in Camden, of which 17,403 (39.6%) were registered as Democrats, 885 (2.0%) were registered as Republicans and 25,601 (58.3%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 4 voters registered to other parties.[160]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 96.8% of the vote (22,254 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 3.0% (683 votes), and other candidates with 0.2% (57 votes), among the 23,230 ballots cast by the city's 47,624 registered voters (236 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 48.8%.[161][162] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 91.1% of the vote (22,197 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain, who received around 5.0% (1,213 votes), with 24,374 ballots cast among the city's 46,654 registered voters, for a turnout of 52.2%.[163] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 84.4% of the vote (15,914 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush, who received around 12.6% (2,368 votes), with 18,858 ballots cast among the city's 37,765 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 49.9.[164]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 79.9% of the vote (6,680 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 18.8% (1,569 votes), and other candidates with 1.4% (116 votes), among the 9,796 ballots cast by the city's 48,241 registered voters (1,431 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 20.3%.[165][166] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 85.6% of the vote (8,700 ballots cast), ahead of both Republican Chris Christie with 5.9% (604 votes) and Independent Chris Daggett with 0.8% (81 votes), with 10,166 ballots cast among the city's 43,165 registered voters, yielding a 23.6% turnout.[167]

Transportation

Roads and highways

As of May 2010, the city had a total of 181.92 miles (292.77 km) of roadways, of which 147.54 miles (237.44 km) were maintained by the municipality, 25.39 miles (40.86 km) by Camden County, 6.60 miles (10.62 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 2.39 miles (3.85 km) by the Delaware River Port Authority.[168]

Interstate 676[169] and U.S. Route 30 run through Camden to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge on the north side of the city. Interstate 76 passes through briefly and interchanges with Interstate 676.

Route 168 passes through briefly in the south, and County Routes 537, 543, 551 and 561 all travel through the heart of the city.

Public transportation

NJ Transit's Walter Rand Transportation Center is located at Martin Luther King Boulevard and Broadway. In addition to being a hub for NJ Transit (NJT) buses in the Southern Division, Greyhound Lines, the PATCO Speedline and River Line make stops at the station.[170]

The PATCO Speedline offers frequent train service to Philadelphia and the suburbs to the east in Camden County, with stations at City Hall, Broadway (Walter Rand Transportation Center) and Ferry Avenue. The line operates 24 hours a day.

Since its opening in 2004, NJ Transit's River Line has offered light rail service to towns along the Delaware north of Camden, and terminates in Trenton. Camden stations are 36th Street, Walter Rand Transportation Center, Cooper Street-Rutgers University, Aquarium and Entertainment Center.

NJ Transit bus service is available to and from Philadelphia on the 313, 315, 317, 318 and 400, 401, 402, 404, 406, 408, 409, 410, 412, 414, and 417, to Atlantic City is served by the 551 bus. Local service is offered on the 403, 405, 407, 413, 418, 419, 450, 451, 452, 453, and 457 lines.[171][172]

Studies are being conducted to create the Camden-Philadelphia BRT, a bus rapid transit system, with a 2012 plan to develop routes that would cover the 23 miles (37 km) between Winslow Township and Philadelphia with a stop at the Walter Rand Transportation Center.[173]

RiverLink Ferry is seasonal service across the Delaware River to Penn's Landing in Philadelphia.[174]

Environmental Issues

Air and water pollution

Situated on the Delaware River waterfront, the city of Camden contains many pollution-causing facilities, such as a trash incinerator and a sewage plant. Despite the additions of new waste-water and trash treatment facilities in the 1970s and 1980s, pollution in the city remains an issue due to faulty waste disposal practices and outdated sewer systems.[41] The open-air nature of the waste treatment plants cause the smell of sewage and other toxic fumes to permeate through the air. This has encouraged local grass roots organizations to protest the development of these plants in Camden.[175] The development of traffic-heavy highway systems between Philadelphia and South Jersey also contributed to the rise of air pollution in the area. Water contamination has been an issue in Camden for decades. In the 1970s, dangerous pollutants were found near the Delaware River at the Puchack Well Field, where many Camden citizens received their household water from, decreasing property values in Camden and causing health problems among the city’s residents. Materials contaminating the water included cancer-causing metals and chemicals, affecting as many as 50,000 people between the early 1970s and late 1990s, when the six Puchack wells were officially shut down and declared a Superfund site.[176]

CCMUA

The Camden City Municipal Utilities Authority, or CCMUA, was established in the early 1970s in order to treat sewage waste in Camden County, by City Democratic chairman and director of public works Angelo Errichetti, who became the authority’s executive director. Errichetti called for a primarily state or federally funded sewage plant, which would have costed $14 million, and a region-wide collection of trash-waste.[41] The sewage plant was a necessity in order to meet the requirements of the Federal Clean Water Act, as per the changes implemented to the act in 1972.[177] James Joyce, chair of the county's Democratic Party at the time, had his own ambitions in regard to establishing a sewage authority that clashed with Errichetti's. Errichetti's political alliance with the county freeholders of Cherry Hill gave him an advantage and Joyce was forced to disband his County Sewerage Authority.[41] The CCMUA originally planned for the sewage facilities in Camden to treat waste water through a primary and secondary process before having it deposited into the Delaware River; however, funding stagnated and byproducts from the plant began to accumulate, causing adverse environmental effects in Camden. Concerned about the harmful chemicals that were being emitted from the waste build-up, the CCMUA requested permission to dump five million gallons of waste into the Atlantic Ocean. Their request was denied and the CCMUA began searching for alternative ways to dispose of the sludge, which eventually lead to the construction of an incinerator, as it was more cost effective than previously proposed methods.[41]

Contamination in Waterfront South

Camden's Waterfront South neighborhood, located in the southern part of the city between the Delaware River and Interstate 676, is home to two dangerously contaminated areas, Welsbach/General Gas Mantle and Martin Aaron, Inc., the former of which has been emanating low-levels of radiation since the early 20th century.[178][179][180] Several industrial pollution sites, including the Camden County Sewage Plant, the County Municipal Waste Combustor, the world’s largest licorice processing plant, chemical companies, auto shops, and a cement manufacturing facility, are present in the Waterfront South neighborhood, which covers less than one square mile. The neighborhood contains 20% of Camden's contaminated areas and over twice the average number of pollution-emitting facilities per New Jersey zip code.[181] According to the Rutgers University Journal of Law and Urban Policy, African-American residents of Waterfront South have a greater chance of developing cancer than anywhere else in the state of Pennsylvania, 90% higher for females and 70% higher for males.[178] 61% of Waterfront South residents have reported respiratory issues, with 48% of residents experiencing chronic chest tightness.[178] Residents of Waterfront South formed the South Camden Citizens in Action, or SCCA, in 1997 in order to combat the environmental and health issues imposed from the rising amount of pollution and the trash-to-steam facilities being implemented by the CCMUA.[178] One such facility, the Covanta Camden Energy Recovery Center (formerly the Camden Resource Recovery Facility), is located on Morgan Street in the Waterfront South neighborhood and burns 350,000 tons of waste from every town in Camden County, aside from Gloucester Township. The waste is then converted into electricity and sold to utility companies that power thousands of homes.[182]

Environmental justice

Residents of Camden have expressed discontent with the implementation of pollution-causing facilities in their city. Father Michael Doyle, a pastor at Waterfront South's Sacred Heart Church, blamed the city's growing pollution and sewage problem as the reason why residents were leaving Camden for the surrounding suburbs.[41] Local groups protested through petitions, referendums, and other methods, such as Citizens Against Trash to Steam (CATS), established by Linda McHugh and Suzanne Marks. In 1999, the St. Lawrence Cement Company reached an agreement with the South Jersey Port Corporation and leased land in order to establish a plant in the Waterfront South neighborhood of Camden, motivated to operate on state land by a reduction in local taxes.[41][178] St. Lawrence received backlash from both the residents of Camden and Camden's legal system, including a law suit that accused the DEP and St. Lawrence of violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964, due to the overwhelming majority of minorities living in waterfront South and the already poor environmental situation in the neighborhood.[41] The cement grinding facility, open year-round, processed approximately 850,000 tons of slag, a substance often used in the manufacturing of cement, and emitted harmful pollutants, such as dust particles, carbon monoxide, radioactive materials, and lead among others.[41] Also, due to the diesel-fueled trucks being used to transport the slag, a total of 77,000 trips, an additional 100 tons of pollutants were produced annually.[36]

Fire department

| Operational area | |

|---|---|

| State | New Jersey |

| City | Camden |

| Agency overview | |

| Established | 1869 |

| Annual calls | ~10,000 |

| Employees | ~200 |

| EMS level | BLS First Responder |

| Facilities and equipment | |

| Divisions | 1 |

| Battalions | 2 |

| Stations | 6 |

| Engines | 5 |

| Ladders | 3 |

| Squads | 1 |

| Rescues | 1 |

| Tenders | 1 |

| HAZMAT | 1 |

| USAR | 1 |

| Fireboats | 1 |

Officially organized in 1869, the Camden Fire Department (CFD) is the oldest paid fire department in New Jersey and is among the oldest paid fire departments in the United States. In 1916, the CFD was the first in the United States that had an all-motorized fire apparatus fleet.[183][184] Layoffs have forced the city to rely on assistance from volunteer fire companies in surrounding communities when firefighters from all 10 fire companies are unavailable due to calls.[185]

The Camden Fire Department currently operates out of six fire stations, located throughout the city in 2 Battalions, commanded by 2 Battalion Chiefs per shift, in addition to an on-duty Deputy Chief. The CFD fire apparatus fleet consists of 5 Engine Companies, 3 Ladder Companies, 1 Squad Company, 1 Rescue Company, and several other special, support, and reserve units. Since 2010, the Camden Fire Department has suffered severe economic cutbacks, including company closures and staffing cuts.[186]

Fire station locations and apparatus

Below is a list of all fire stations and company locations in the city of Camden according to Battalion.

| Engine company | Ladder Company | Special Unit | Chief | Battalion | Address | Neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine 1 | Ladder 1 | Car 1(Chief of Department), Car 2(Assistant Chief), Car 3(Deputy Chief), Car 4(Deputy Chief), Car 5(Fire Marshal) | 1 | 4 N. 3rd St. | Center City | |

| Squad 7 | 2 | 1115 Kaighns Ave. | Whitman Park | |||

| Engine 8 | Ladder 2 | Rescue 1, Rescue 2(USAR/Collapse Unit), Haz-Mat. 1 | Battalion 1 | 1 | 1301 Broadway | South Camden |

| Engine 9 | Tower Ladder 3 | Battalion 2 | 2 | 3 N. 27th St. | East Camden | |

| Engine 10 | 1 | 2500 Morgan Blvd. | South Camden | |||

| Engine 11 | 2 | 901 N. 27th St. | Cramer Hill |

Waterfront

One of the most popular attractions in Camden is the city's waterfront, along the Delaware River. The waterfront is highlighted by its four main attractions, the USS New Jersey; the BB&T Pavilion; Campbell's Field; and the Adventure Aquarium.[187] The waterfront is also the headquarters for Catapult Learning, a provider of K−12 contracted instructional services to public and private schools in the United States, and WebiMax, a full-service internet marketing company.

The Adventure Aquarium was originally opened in 1992 as the New Jersey State Aquarium at Camden. In 2005, after extensive renovation, the aquarium was reopened under the name Adventure Aquarium.[188] The aquarium was one of the original centerpieces in Camden's plans to revitalize the city.[189]

The Susquehanna Bank Center (formerly known as the Tweeter Center) is a 25,000-seat open-air concert amphitheater opened in 1995 and renamed after a 2008 deal in which the bank would pay $10 million over 15 years for naming rights.[190]

Campbell's Field, opened in 2001, was home to the Camden Riversharks (which folded in 2015)[191] of the independent Atlantic League; and the Rutgers–Camden baseball team.

The USS New Jersey (BB-62) was a U.S. Navy battleship that was intermittently active between the years 1943 and 1991. After its retirement, the ship was turned into the Battleship New Jersey Museum and Memorial, opened in 2001 along the waterfront. The New Jersey saw action during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and provided support off Lebanon in early 1983.[192]

Other attractions at the Waterfront are the Wiggins Park Riverstage and Marina, One Port Center, The Victor Lofts, the Walt Whitman House,[193] the Walt Whitman Cultural Arts Center, the Rutgers–Camden Center For The Arts and the Camden Children's Garden.

In June 2014, the Philadelphia 76ers announced that they would move their practice facility and home offices to the Camden Waterfront, adding 250 permanent jobs in the city creating what CEO Scott O'Neil described as "biggest and best training facility in the country" using $82 million in tax savings offered by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.[194][195]

The Waterfront is also served by two modes of public transportation. NJ Transit serves the Waterfront on its River Line, while people from Philadelphia can commute using the RiverLink Ferry, which connects the Waterfront with Old City Philadelphia.[196]

Riverfront State Prison,[197] was a state penitentiary located near downtown Camden north of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, which opened in August 1985 having been constructed at a cost of $31 million.[198] The prison had a design capacity of 631 inmates, but housed 1,020 in 2007 and 1,017 in 2008.[199] The last prisoners were transferred in June 2009 to other locations and the prison was closed and subsequently demolished, with the site expected to be redeveloped by the State of New Jersey, the City of Camden, and private investors.[200] In December 2012, the New Jersey Legislature approved the sale of the 16-acre (6.5 ha) site, considered surplus property to the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.[201]

Education

Public schools

Camden's public schools are operated by Camden City Public Schools district. As of the 2011–12 school year, the district's 30 schools had an enrollment of 13,723 students and 1,307.9 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 10.49:1.[202] The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide,[203] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[204][205]

High schools in the district (with 2011–12 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[206]) are:

- Brimm Medical Arts High School[207] (213; 9–12)

- Camden High School[208] (868; 9–12)

- Creative Arts Morgan Village Academy[209] (488; 6–12)

- MetEast High School[210] (117; 9–12)

- Woodrow Wilson High School[211] (959; 9–12)

Charter Schools

An important transition to education in Camden was when Chris Christie announced on March 25, 2013 at Woodrow Wilson High school that the sate of New Jersey would be taking over administration of the public schools in the city of Camden. The Department of Education had done an investigation that found in 2012 ,graduation rates fell 49.27%, down from 56.89% the year before. From 2011 to 2012, only 2% of camden students scored above a 1550 out of a possible 2400 on the scholastic Aptitude Test(SAT), compared with 43% students nationally. Only 19% and 30.4% of third-through eight-grade students tested proficient in language arts and in math, respectively, both numbers are below state average. Therefore, Chris Christie felt he had to take partnership with the state of New Jersey.

Camden is not the first city to be taken over by the state. Other cities like Jersey City in 1989, Paterson in 1991, Newark in 1995[212] and are currently being operated by state control according to Barbara Morgan, a spokeswoman for the New Jersey Deparment of Education.

Christie claimed, " I can't be a guarantor of results, none of us can, but just because we can't guarantee a positive result or because there have been some mixed results in the past, should not be used as in excuse for inaction".

On February 5, 2015 superintendent Paymon Rhouhanifard announced that the 105 year old J.G Whittier Family School will permiantely be closed at the end of 2015.[213]

The Henry L. Bonsai Family School is becoming Camden Prep Bonsall Elementary under Renaissance charter system, East Camden Middle School will become Master, Francis X. Mc Graw Elementary School and Rafael Cordero Molina Elementary School is going to be Master. The J.G Whittier Family school will become part of the KIPP Cooper Norcross Academy charter school system.

Students were given the option to stay with the school under their transition or seek other alternatives.

On March 9, 2015 the first year of new Camden Charter Schools the enrollment raised concern. Mastery and Uncommon charter schools failed to meet enrollment projections for their first year of operation by 15% and 21%, according to Education Law Center.[214] Also, the KIPP and Uncommon Charter Schools had enrolled students with disabilities and English Language learners at a level far below the enrollment of these students in the Camden district. The enrollment data on the Mastery, Uncommon and KIPP charter chains comes form the state operated Camden district and raised questions whether or not the data is viable, especially since it had said that Camden parents prefer charters over neighborhood public schools. In addition, there was a concern that these charter schools are not serving students with special needs at comparable level to district enrollment, developing the idea of growing student segregation and isolation in Camden schools as these chains expand in the coming years.

On October 2016, Governor Chris Christie, Camden Mayor Dana L. Redd, Camden Public Schools Superintendent Paymon Rouhanifard, and state and local representatives announced a historical $133 million investment of a new Camden High School Project.[215] The new school is planned to be ready for student occupancy in 2021. It would have 9th and 12th grade. The school has a history of a 100 years and has needed endless repairs. The plan is to give students a 21st century education.

Chris Christie states, " This new, state-of-the-art school will honor the proud tradition of the Castle on the Hill, enrich our society and improve the lives of students and those around them".

Charter/Renaissance schools in Camden

- Hope Community CS 836 S. 4th Street Camden, NJ 08103

- Freedom Prep Charter School 1000 Atlantic ave Camden, NJ 08104

- Environment Community Opportunity Charter School 817 Carpenter street, Bridgeview complex camden, NJ 08102)

- Camden's Promise Charter School 879 Beideman Ave Camden, NJ 08105

- Camden Community Charter School 9th & Linden Streets Camden, NJ 08102

- Leap Academy University Charter School 549 Cooper street, Camden, NJ 08102

- Kipp Academy has four schools in one.

Private education

Holy Name School, Sacred Heart Grade School, St. Anthony of Padua School and St. Joseph Pro-Cathedral School are K-8 elementary schools operating under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Camden.[216] They operate as four of the five schools in the Catholic Partnership Schools, a post-parochial model of Urban Catholic Education.[217] The Catholic Partnership Schools are committed to sustaining safe and nurturing schools that inspire and prepare students for rigorous, college preparatory secondary schools or vocations.

Higher education

The University District, adjacent to the downtown, is home to the following institutions:

- Camden County College – one of three main campuses, the college first came to the city in 1969, and constructed a campus building in Camden in 1991.[218]

- Rowan University at Camden, satellite campus – the Camden campus began with a program for teacher preparation in 1969 and expanded with standard college courses the following year and a full-time day program in 1980.[219]

- Cooper Medical School of Rowan University[220]

- Rutgers University–Camden – the Camden campus, one of three main sites in the university system, began as South Jersey Law School and the College of South Jersey in the 1920s and was merged into Rutgers in 1950.[221]

- Camden College of Arts & Sciences[222]

- School of Business – Camden[223]

- Rutgers School of Law-Camden[224]

- University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)

- Affiliated with Cooper University Hospital

- Coriell Institute for Medical Research[225]

- Affiliated with Cooper University Hospital

- Affiliated with Rowan University

- Affiliated with University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Libraries

The city was once home to two Carnegie libraries, the Main Building[226] and the Cooper Library in Johnson Park.[227] The city's once extensive library system has been beleaguered by financial difficulties and in 2010 threatened to close at the end of the year, but was incorporated into the county system.[228][229] The main branch closed in February 2011,[230] and was later reopened by the county in the bottom floor of the Paul Robeson Library at Rutgers University.[231]

In addition to the Paul Robeson Library at Rutgers University, there are academic libraries at Cooper Medical School at Rowan and Camden County College.

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Logo |

| Camden Riversharks (from 2001-2015) | Baseball | Atlantic League of Professional Baseball | Campbell's Field |

Crime

| Camden | |

| Crime rates (2009) | |

| Crime type | Rate* |

|---|---|

| Homicide: | 34 |

| Robbery: | 766 |

| Aggravated assault: | 1,020 |

| Total violent crime: | 1,880 |

| Burglary: | 1,035 |

| Larceny-theft: | 2,251 |

| Motor vehicle theft: | 649 |

| Arson: | 137 |

| Total property crime: | 3,935 |

| Notes * Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2009 population: 78,980 |

|

| Source: 2009 FBI UCR Data | |

Morgan Quitno has ranked Camden as one of the top ten most dangerous cities in the United States since 1998, when they first included cities with populations less than 100,000. Camden was ranked as the third-most dangerous city in 2002. Camden was ranked as the most dangerous city overall in 2004 and 2005.[232][233] It improved to the fifth spot for the 2006 and 2007 rankings but rose to number two in 2008[234][235][236] and to the most dangerous spot in 2009.[237] Morgan Quitno based its rankings on crime statistics reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in six categories: murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, and auto theft.[238] In The Nation, journalist Chris Hedges describes Camden as "the physical refuse of postindustrial America",[239] plagued with homelessness, drug trafficking, prostitution, robbery, looting, constant violence, and an overwhelmed police force (which in 2011 lost nearly half of its officers to budget-related layoffs).[240]

In 2005, reported homicides in Camden dropped to 34, 15 fewer murders than in 2004.[241] Though Camden's murder rate was still much higher than the national average, the reduction in 2005 was a drop of over 30%. In 2006, the number of murders climbed to 40. While murders fell by 10% across New Jersey in 2009, Camden's murder rate declined from 55 in 2008 down to 33, a drop of 40% that was credited to anti-gang efforts and more firearms seizures.[242] Despite significant cuts in the police department due to the city's fiscal difficulties, murders in 2009 and 2010 were both under 40, staying below the peak that had occurred in 2008, and continued to decline into early 2011. However, in 2012, the city's murder rate spiked and reached 62.[243]

On October 29, 2012, the FBI announced Camden was ranked first in violent crime per capita of cities with over 50,000 residents, surpassing Flint, Michigan.[244] In December 2012, Camden residents surrendered approximately 1,137 firearms to two local churches over a two-day period.[245]

Law enforcement

In 2015, the Camden Police Department was operated by the state.[246] In 2011, it was announced that a county police department would be formed.[247] On May 1, 2013, the police department was disbanded and the newly created Camden County Police Department took over full responsibility for policing the city of Camden.[248]

Points of interest

- Adventure Aquarium – Originally opened in 1992, it re-opened in its current form in May 2005 featuring about 8,000 animals living in varied forms of semi-aquatic, freshwater, and marine habitats.[249]

- BB&T Pavilion – An outdoor amphitheater/indoor theater complex with a seating capacity of 25,000. Formerly known as the Susquehanna Bank Center.

- Battleship New Jersey Museum and Memorial – Opened in October 2001, providing access to the battleship USS New Jersey that had been towed to the Camden area for restoration in 1999.[250]

- Campbell's Field – a 6,425-seat baseball park that hosted its first regular season baseball game on May 11, 2001, and is home to the Camden Riversharks and the Rutgers University–Camden baseball team. The stadium was acquired by Camden County in April 2015.[251]

- Harleigh Cemetery – Established in 1885, the cemetery is the burial site of Walt Whitman, several Congressmen, and many other South Jersey notables.[252]

- Walt Whitman House

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Camden County, New Jersey

In popular culture

The fictional Camden mayor Carmine Polito in the 2013 film American Hustle is loosely based on 1970s Camden mayor Angelo Errichetti.[253]

The 1995 film 12 Monkeys contains scenes on Camden's Admiral Wilson Boulevard.[254]

In season 3 episode 19, Self-Destruct of The CW Television show Nikita, Camden is portrayed. Alex and Nikita destroys a drug and human trafficking gang and their headquarters.

Notable people

People who were born in, are residents of, or have otherwise been closely connected to Camden include:

- Max Alexander (born 1981), boxer who was participant in ESPN reality series The Contender 3.[255]

- Christine Andreas (born 1951), Broadway actress and singer.[256]

- Rob Andrews (born 1957), U.S. Representative for New Jersey's 1st congressional district, served 1990–2014.[257]

- Joe Angelo (1896–1978), U.S. Army veteran of World War I and recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross.[258]

- Mary Ellen Avery (1927–2011), pediatrician whose research led to development of successful treatment for Infant respiratory distress syndrome.[259]

- Vernon Howe Bailey (1874–1953), artist.[260]

- David Baird Jr. (1881–1955), U.S. Senator from 1929 to 1930, unsuccessful Republican nominee for governor in 1931.[261]

- David Baird Sr. (1839–1927), United States Senator from New Jersey.[262]

- Rashad Baker (born 1982), professional football safety for Buffalo Bills, Minnesota Vikings, New England Patriots, Philadelphia Eagles and Oakland Raiders.[263]

- Butch Ballard (1918–2011), jazz drummer who performed with Louis Armstrong, Count Basie and Duke Ellington.[264]

- Arthur Barclay (born 1982), politician who served on the Camden City Council for two years and has represented the 5th Legislative District in the New Jersey General Assembly since 2016.[265]

- U. E. Baughman (1905–1978), head of United States Secret Service from 1948 to 1961.[266]

- Carla L. Benson, vocalist best known for her recorded background vocals.[267]

- Martin V. Bergen (1872–1941), lawyer, college football coach.[268]

- Art Best (1953–2014), football running back who played three seasons in the National Football League with the Chicago Bears and New York Giants.[269][270]

- Audrey Bleiler (1933–1975), played in All-American Girls Professional Baseball League for 1951–1952 South Bend Blue Sox champion teams.[271]

- William J. Browning (1850–1920), represented New Jersey's 1st congressional district in U.S. House of Representatives, 1911–1920.[272]

- Stephen Decatur Button (1813–1897), architect; designer of schools, churches and Camden's Old City Hall (1874–75, demolished 1930).[273][274]

- Frank Chapot (1932–2016), Olympic silver medalist equestrian.[275]

- Boston Corbett (1832–1894), Union Army soldier who killed John Wilkes Booth.[276][277]

- Mary Keating Croce (1928–2016), politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly for three two-year terms, from 1974 to 1980, before serving as the Chairwoman of the New Jersey State Parole Board in the 1990s.[278]

- Donovin Darius (born 1975), professional football player for Jacksonville Jaguars.[279][280]

- Rachel Dawson (born 1985), field hockey midfielder.[281][282]

- Buddy DeFranco (1923–2014), jazz clarinetist.[283]

- Rawly Eastwick (born 1950), Major League Baseball pitcher who won two games in 1975 World Series.[284][285]

- Lola Falana (born 1942), singer and dancer.[286]

- Carmen M. Garcia, former Chief judge of Municipal Court in Trenton, New Jersey.[287]

- George Hegamin (born 1973), offensive lineman who played for NFL's Dallas Cowboys, Philadelphia Eagles and Tampa Bay Buccaneers.[288]

- Heather Henderson (born 1973), singer, model, podcaster, actress, Dance Party USA performer[289]

- Richard Hollingshead (1900–1975), inventor of the drive-in theater.[290]

- Richard "Groove" Holmes (1931–1991), jazz organist.[291]

- John J. Horn (1917–1999), labor leader and politician who served in both houses of the New Jersey Legislature before being nominated to serve as commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Labor and Industry.[292]

- Leon Huff (born 1942), songwriter and record producer.[293]

- Barbara Ingram (1947–1994), R&B background singer.[294]

- Eric Louis (ELEW) (born 1973), pianist.[295]

- Robert S. MacAlister (1897–1957), Los Angeles City Council member, 1934–39.[296]

- Aaron McCargo Jr. (born 1971), chef and television personality who hosts Big Daddy's House, a cooking show on Food Network.[297][298][299][300]

- Lucy Taxis Shoe Meritt (1906–2003), classical archaeologist and a scholar of Greek architectural ornamentation and mouldings.[301]

- Richard Mroz, President of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities.[302]

- Ray Narleski (1928–2012), baseball player with Cleveland Indians and Detroit Tigers.[303]

- Francis F. Patterson, Jr. (1867–1935), represented New Jersey's 1st congressional district in U.S. House of Representatives, 1920–1927.[304]

- Jim Perry (1933–2015), game show host and television personality.[305]

- Harvey Pollack (1922–2015), director of statistical information for the Philadelphia 76ers, who at the time of his death held the distinction of being the only individual still working for the NBA since its inaugural 1946–47 season.[306]

- Dwight Muhammad Qawi (born 1953), boxing world light-heavyweight and cruiserweight champion, International Boxing Hall of Famer known as the "Camden Buzzaw".[307]

- Buddy Rogers (1921–1992), professional wrestler.[308]

- Mike Rozier (born 1961), collegiate and professional football running back who won Heisman Trophy in 1983.[309]

- John F. Starr (1818–1904), represented New Jersey's 1st congressional district in U.S. House of Representatives, 1863–1867.[310]

- Richard Sterban (born 1943), member of the Oak Ridge Boys.[311]

- Mickalene Thomas (born 1970), artist.[312]

- Billy Thompson (born 1963), college and professional basketball player who played for the Los Angeles Lakers and Miami Heat.[313]

- Sheena Tosta (born 1982), hurdler, Olympic silver medalist 2008.[314]

- Howard Unruh, (1921–2009), 1949 mass murderer.[53]

- Nick Virgilio (1928–1989), haiku poet.[315]

- Dajuan Wagner (born 1983), professional basketball player for Cleveland Cavaliers, 2002–2005, and Polish team Prokom Trefl Sopot.[316]

- Jersey Joe Walcott (1914–1994), boxing world heavyweight champion, International Boxing Hall of Famer.[317]

- Walt Whitman (1819–1892), iconic essayist, journalist and poet.[318]

- Phil Zimmermann (born 1954), programmer who developed Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), a type of data encryption.[319]

References

- ↑ Anthony DePalma, "The Talk of Camden; A City in Pain Hopes for Relief Under Florio", The New York Times, February 7, 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 2010 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey County Subdivisions, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2015.

- 1 2 US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- 1 2 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 28.

- 1 2 Mayor's Office, City of Camden. Accessed June 24, 2016.

- ↑ 2016 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ↑ Office of the Business Administrator, City of Camden. Accessed December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Office of the City Clerk, City of Camden. Accessed July 2, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: City of Camden, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 DP-1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Camden city, Camden County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 1, 2011.

- 1 2 3 The Counties and Most Populous Cities and Townships in 2010 in New Jersey: 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed November 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Municipalities Grouped by 2011–2020 Legislative Districts, New Jersey Department of State, p. 3. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Camden city, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- 1 2 PEPANNRES - Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - 2015 Population Estimates for New Jersey municipalities, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 22, 2016.

- 1 2 GCT-PH1 Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 – State – County Subdivision from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 4, 2012.

- ↑ Look Up a ZIP Code, United States Postal Service. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- ↑ Zip Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- ↑ Area Code Lookup – NPA NXX for Camden, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 22, 2013.

- 1 2 American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- ↑ "A Cure for the Common Codes: New Jersey", Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed July 2, 2012.

- ↑ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Find a County Archived May 31, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., National Association of Counties. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Camden County, NJ, National Association of Counties. Accessed January 20, 2013.

- ↑ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed July 2, 2012.

- ↑ Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 104. Accessed January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 65. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- 1 2 Staff. "Milan Begins Sentence", The New York Times, July 16, 2001. Accessed July 2, 2012. "Former Mayor Milton Milan, 38, convicted of corruption charges in December, is now serving his seven-year sentence at a low-security federal prison in Loretto, Pa., where he was transferred Friday. ... On June 15, Mr. Milan was sentenced on 14 counts of corruption, including taking payoffs from the mob, as well as concealing the source of a $65,000 loan from a drug kingpin."

- ↑ Giordano, Rita; and Purcell, Dylan. "Third of N.J. districts in area top state average in per-pupil spending", Philadelphia Inquirer, May 21, 2011. Accessed August 12, 2012 ."Coming in at No. 6 statewide and first locally among K-12s was Camden, at $23,770 per student counting the new items – a 4 percent increase over 2008–09. In Camden, total per-student spending minus the added costs included this year – the 'budgetary per-pupil cost' – was $19,118."

- ↑ Ly, Laura. "State of New Jersey stepping in to run Camden's troubled schools", CNN, March 25, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Fast Facts: US High School Dropout Rates, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Terruso, Julia. "A look at what SAT report on Camden means", The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 22, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2014. "A statistic released by the Camden School District – that three out of about 882 high school seniors scored "college ready" on the SAT in 2012 – sparked criticism and questions from education advocates last week. The number, based on state performance reports from the 2011–12 school year, uses the College Board's college-readiness parameter score of 1550 out of 2400 on math, reading and writing."

- ↑ Staff. "Camden's crisis: Ungovernable? The state may have failed the city it took over", The Economist, November 26, 2009. Accessed July 29, 2014. "Camden spends $17,000 per child on education, yet only two thirds complete school. Two out of five people live below the poverty line."

- ↑ Crime in the United States 2012: NEW JERSEY Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by City, 2012, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Accessed December 20, 2014.

- ↑ Crime in the United States 2012: Violent Crime, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Accessed December 20, 2014. "There were an estimated 386.9 violent crimes per 100,000 inhabitants in 2012, a rate that remained virtually unchanged when compared to the 2011 estimated rate."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "History | City of Camden". www.ci.camden.nj.us. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- ↑ Greenberg, Gail. County History, Camden County, New Jersey. Accessed July 3, 2011.

- ↑ Cooper, Howard M. "Historical Sketch of Camden", Camden County Historical Society, June 13, 1899. Accessed December 20, 2014.

- ↑ Fisler, Lorenzo F. (1858). A local history of Camden, commencing with its early settlement, incorporation and public and private improvements: brought up to the present day. Camden, NJ: Francis A. Cassedy. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ↑ Haines family. Cooper's Ferry daybook, 1819–1824. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Gillette, Jr., Howard (2006). Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-8122-1968-6.

- ↑ "Rutgers University Computing Services – Camden"

- ↑ O'Reilly, David. "An RCA museum grows at Rowan", The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 27, 2013. Accessed October 13, 2015. " Radio Corp. of America's "contributions to South Jersey were enormous," said Joseph Pane, deputy director of the RCA Heritage Program at Rowan, which he helped create two years ago.'At its peak in the 1960s it employed 12,000 people; 4,500 were engineers.'"

- ↑ New York Shipbuilding, Camden NJ, Shipbuilding History, March 17, 2014. Accessed October 13, 2015. "At its peak, New York Ship employed 30,000 people. It continued in both naval and merchant shipbuilding after WWII but closed in 1967."

- ↑ "Made in S.J.: Campbell Soup Co.". Portal to gallery of photographs (20) related to The Campbell Soup Company. Courier-Post. Undated. Accessed December 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Made in S.J.: Shipbuilding". Portal to gallery of photographs (16) related to shipbuilding in Camden. Courier-Post. Undated. Accessed December 25, 2009.

- ↑ Encarta Encyclopedia: Ship. Accessed June 23, 2006. Archived October 31, 2009.

- ↑ Staff. "Unnecessary excellence: what public-housing design can learn from its past.", Harper's Magazine, March 1, 2005. Accessed July 3, 2011. "'If it indicates the kind of Government housing that is to follow, we may all rejoice.' So wrote a critic for The Journal of the American Institute of Architects in 1918 about Yorkship Village, one of America's first federally funded public-housing projects. Located in Camden, New Jersey, Yorkship Village was designed to be a genuine neighborhood, as can be seen from these original architectural plans."

- ↑ "Made in S.J.: RCA Victor". Portal to gallery of photographs (22) related to the Victor Talking Machine Company. Courier-Post, January 30, 2008. Accessed July 3, 2011.

- ↑ Staff. "General Electric gets go-ahead to acquire RCA", Houston Chronicle, June 5, 1986. Accessed July 3, 2011. "The Federal Communications Commission cleared the way today for General Electric Co. to acquire RCA Corp. and its subsidiaries, including the NBC network. In allowing the transfer of RCA, the commission rejected four petitions to block the $6.28 billion deal.'