Carcinoid syndrome

| Carcinoid syndrome | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E34.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 259.2 |

| ICD-O | M8240/3-8245 |

| DiseasesDB | 2040 |

| MedlinePlus | 000347 |

| eMedicine | med/271 |

| MeSH | D008303 |

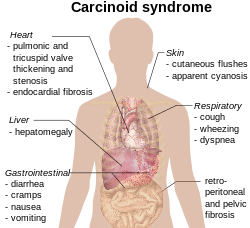

Carcinoid syndrome is a paraneoplastic syndrome comprising the signs and symptoms that occur secondary to carcinoid tumors. The syndrome includes flushing and diarrhea, and, less frequently, heart failure and bronchoconstriction.[1] It is caused by endogenous secretion of mainly serotonin and kallikrein.

Signs and symptoms

The carcinoid syndrome occurs in approximately 5% of carcinoid tumors[3] and becomes manifest when vasoactive substances from the tumors enter the systemic circulation escaping hepatic degradation. Interestingly, if the primary tumor is from the GI tract (hence releasing serotonin into the hepatic portal circulation), carcinoid syndrome generally does not occur until the disease is so advanced that it overwhelms the liver's ability to metabolize the released serotonin.

- Flushing: The most important clinical finding is flushing of the skin, usually of the head and the upper part of thorax.[4]

- Diarrhea: When the diarrhea is intensive it may lead to electrolyte disturbance and dehydration. Other associated symptoms are nausea, and vomiting.

- Bronchoconstriction, which may be histamine-induced, affects a smaller number of patients and often accompanies flushing.

- Secondary restrictive cardiomyopathy: About 50% of patients have cardiac abnormalities classically of the restrictive-type caused by serotonin-induced fibrosis of the valvular endocardium, notably the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, called cardiac fibrosis. This results in a heart with normal rhythm and contractility, but reduced preload and end-diastolic volume. "TIPS" is an acronym for Tricuspid Insufficiency, Pulmonary Stenosis (fibrosis of tricuspid and pulmonary valves).

- Abdominal pain: Due to desmoplastic reaction of the mesentery or hepatic metastases.

Pathophysiology

Carcinoid tumors produce the vasoactive substance, serotonin. It is commonly, but incorrectly, thought that serotonin is the cause of the flushing. The flushing results from secretion of kallikrein, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of kininogen to lysyl-bradykinin. The latter is further converted to bradykinin, one of the most powerful vasodilators known. Other components of the carcinoid syndrome are diarrhea (probably caused by the increased serotonin, which increases peristalsis, leaving less time for fluid absorption), a pellagra-like syndrome (probably caused by diversion of large amounts of tryptophan from synthesis of the vitamin B3 niacin, which is needed for NAD production, to the synthesis of serotonin and other 5-hydroxyindoles), fibrotic lesions of the endocardium, particularly on the right side of the heart resulting in insufficiency of the tricuspid valve and, less frequently, the pulmonary valve and, uncommonly, bronchoconstriction. The pathogenesis of the cardiac lesions and the bronchoconstriction is unknown, but the former probably involves activation of serotonin 5-HT2B receptors by serotonin. When the primary tumor is in the gastrointestinal tract, as it is in the great majority of cases, the serotonin and kallikrein are inactivated in the liver; manifestations of carcinoid syndrome do not occur until there are metastases to the liver or when the cancer is accompanied by liver failure (cirrhosis). Carcinoid tumors arising in the bronchi may be associated with manifestations of carcinoid syndrome without liver metastases because their biologically active products reach the systemic circulation before passing through the liver and being metabolized.

In most patients, there is an increased urinary excretion of 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid), a degradation product of serotonin.

The biology of these tumors is interesting as it differs from many other tumor types. Ongoing research on the biology of these tumors may reveal new mechanisms for tumor development.[5]

Diagnosis

With a certain degree of clinical suspicion, the most useful initial test is the 24-hour urine levels of 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid), the end product of serotonin metabolism. Patients with carcinoid syndrome usually excrete more than 25 mg of 5-HIAA per day.

Imaging

For localization of both primary lesions and metastasis, the initial imaging method is Octreoscan, where indium-111 labelled somatostatin analogues (octreotide) are used in scintigraphy for detecting tumors expressing somatostatin receptors. Median detection rates with octreoscan are about 89%, in contrast to other imaging techniques such as CT scan and MRI with detection rates of about 80%. Gallium-68 labelled somatostatin analogues such as 68Ga-DOTA-Octreotate (DOTATATE), performed on a PET/CT scanner is superior to conventional Octreoscan.

Usually on CT scan, a spider-like/crab-like change is visible in the mesentery due to the fibrosis from the release of serotonin. 18F-FDG PET/CT, which evaluate for increased metabolism of glucose, may also aid in localizing the carcinoid lesion or evaluating for metastases. Chromogranin A and platelets serotonin are increased.

Localization of tumour

Tumour localization may be extremely difficult. Barium swallow and follow-up examination of the intestine may occasionally show the tumour. Capsule video endoscopy has recently been used to localize the tumour. Often laparotomy is the definitive way to localize the tumour.

Treatment

For symptomatic relief of carcinoid syndrome:

- Octreotide (a somatostatin analogue which decreases the secretion of serotonin by the tumor and, secondarily, decreases the breakdown product of serotonin (5-HIAA))

- Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with lutetium-177, yttrium-90 or indium-111 labeled to octreotate is highly effective

- Methysergide maleate (antiserotonin agent but not used because of the serious side effect of retroperitoneal fibrosis)

- Cyproheptadine (an antihistamine drug with antiserotonergic effects)

Alternative treatment for qualifying candidates:

- Surgical resection of tumor and chemotherapy (5-FU and doxorubicin)

- Endovascular, chemoembolization, targeted chemotherapy directly delivered to the liver through special catheters mixed with embolic beads (particles that block blood vessels), used for patients with liver metastases.

Uncertainties

Disease progression is difficult to ascertain because the disease can metastasize anywhere in the body and can be too small to identify with any current technology. Markers of the condition such as chromogranin-A are imperfect indicators of disease progression.[6]

Prognosis

Prognosis varies from individual to individual. It ranges from a 95% 5-year survival for localized disease to an 80% 5-year survival for those with liver metastases. The average survival time from the start of octreotide treatment has increased to about 12 years.

Synonyms

- Thorson-Bioerck syndrome

- Argentaffinoma syndrome

- Cassidy-Scholte syndrome

- Flush syndrome

See also

References

- ↑ Soga J, Yakuwa Y, Osaka M (1999). "Carcinoid syndrome: a statistical evaluation of 748 reported cases". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 18 (2): 133–41. PMID 10464698.

- ↑ Table 15-14 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

- ↑ Warrell; et al. (2010). Oxford Textbook of Medicine (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262922-0.

- ↑ E.Goljan, Pathology, 2nd ed Mosby Elsevier, Rapid Review series.

- ↑ Cunningham JL, Janson ET (2011). "The biological hallmarks of ileal carcinoids". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 41 (12): 1353–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02537.x. PMID 21605115.

- ↑ Nobels FR, Kwekkeboom DJ, Bouillon R, Lamberts SW (1998). "Chromogranin A: its clinical value as marker of neuroendocrine tumours". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 28 (6): 431–40. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00305.x. PMID 9693933.

Further reading

- Carrasco CH, Charnsangavej C, Ajani J, Samaan NA, Richli W, Wallace S (1986). "The carcinoid syndrome: palliation by hepatic artery embolization". American Journal of Roentgenology. 147 (1): 149–54. doi:10.2214/ajr.147.1.149. PMID 2424291.

- Mabvuure N, Cumberworth A, Hindocha S (2012). "In patients with carcinoid syndrome undergoing valve replacement: will a biological valve have acceptable durability?". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 15 (3): 467–71. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivs212. PMC 3422934

. PMID 22691379.

. PMID 22691379.

.svg.png)