Chang and Eng Bunker

| Chang and Eng Bunker | |

|---|---|

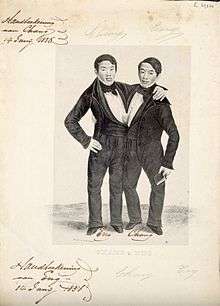

A painting of Chang (right) and Eng Bunker (left), circa 1836 | |

| Born |

May 11, 1811 Samutsongkram, Siam (now Thailand) |

| Died |

January 17, 1874 (aged 62) Mount Airy, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Cause of death |

Stroke Heart attack |

| Resting place | White Plains Baptist Church Cemetery |

| Citizenship |

Siamese American |

| Occupation | Thai family |

| Years active | 1834-1874 |

| Spouse(s) |

Adelaide Yates (m. 1843–74) (Chang) Sarah Anne Yates (m. 1843–74) (Eng) |

| Children |

12 (Chang) 10 (Eng)[1][2] |

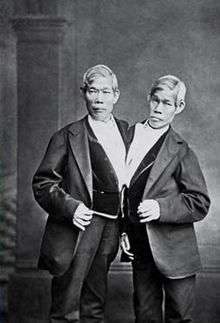

Chang (pinyin: Chāng; rtgs: Chan) and Eng (pinyin: Ēn; rtgs: In) Bunker (May 11, 1811 – January 17, 1874) were Thai-American conjoined twin brothers whose condition and birthplace became the basis for the term "Siamese twins".[3][4][5]

Life

The Bunker brothers were born on May 11, 1811, in the province of Samutsongkram, near Bangkok, in the Kingdom of Siam (today's Thailand). Their fisherman father was a Chinese Thai, while their mother, Nok, (rtgs: Nak) was half-Chinese and half-Malay.[6] Because of their Chinese heritage,[7] they were known locally as the "Chinese Twins".[8] The brothers were joined at the sternum by a small piece of cartilage, and though their livers were fused, they were independently complete.

In 1829, Robert Hunter, a Scottish merchant who lived in Bangkok, saw the twins swimming and realized their potential. He paid their parents to permit him to exhibit their sons as a curiosity on a world tour. When their contract with Hunter was over, Chang and Eng went into business for themselves. In 1839, while visiting Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the brothers were attracted to the area and purchased a 110-acre (0.45 km2) farm in nearby Traphill.

Determined to live as normal a life they could, Chang and Eng settled on their small plantation and bought slaves to do the work they could not do themselves.[9] Using their adopted name "Bunker", they married local women on April 13, 1843. Chang wed Adelaide Yates (1823-1917), while Eng married her sister, Sarah Anne (1822-1892). The twins also became naturalized American citizens.[10]

The couples shared a bed built for four in their Traphill home. Chang and Adelaide would become the parents of twelve children. Eng and Sarah had ten.[1][2] However, Chichester disputes this number of children, stating Eng had 11.[11] After a number of years, the sisters began to dislike each other[12] and separate households were set up west of Mount Airy, North Carolina in the town of White Plains. The brothers would alternately spend three days at each home. During the American Civil War, Chang's son Christopher and Eng's son Stephen both served in the Confederate army. The twins lost most of their money with the defeat of the Confederacy and became very bitter. They returned to public exhibitions, but this time they had little success. Nevertheless, they maintained a high reputation for honesty and integrity, and they were highly respected by their neighbors.[12]

Later years and death

In 1870, Chang suffered a stroke and his health declined over the next four years. He also began drinking heavily (Chang's drinking did not affect Eng as they did not share a circulatory system). Despite his brother's ailing condition, Eng remained in good health. Shortly before his death, Chang was injured after falling from a carriage. He then developed a severe case of bronchitis. On January 17, 1874, Chang died while the brothers were asleep. Eng awoke to find his brother dead and cried, "Then I am going". A doctor was summoned to perform an emergency separation, but he was too late. Eng died approximately three hours later.

An autopsy revealed that Chang had died of a cerebral blood clot but Eng's cause of death remains uncertain. Doctors of the time theorized that Eng died of shock due to fear of his impending death. They based that theory on the fact that Eng's bladder had distended with urine and his right testicle had retracted.[11] Two North Carolina neurologists, Dr. Paul D. Morte and Dr. E. Wayne Massey, reviewed the case and concluded that Chang likely died of pulmonary edema and heart failure. They also dismissed the claim that Eng died of shock and attributed the muscle cramping that caused his testicle to retract to "acrocyanosis from induced vasospasm and microthrombi due to disseminated intravascular coagulation, the tissue factor released from necrotic tissue and the endotoxin from sepsis activating coagulation cascade".[10]

Sarah Anne Bunker (Eng's widow) died on April 29, 1892, and Adelaide Bunker (Chang's widow) died on May 21, 1917.

Legacy

- The fused liver of the Bunker brothers was preserved and is currently on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[13] Numerous artifacts of the twins, including some of their personal artifacts and their travel ledger, are displayed in the North Carolina Collection Gallery in Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; this includes the original watercolor portrait of Chang and Eng from 1836.

- Mark Twain wrote a short story, The Siamese Twins,[14] based on the Bunkers.

- In 1996, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a 90-minute radio play called United States about the lives and deaths of Chang and Eng Bunker. The writer was Tony Coult and the director was Andy Jordan. Transmission was on June 17, with a cast that included Bert Kwouk and Ozzie Yue as the twins.

- A Singapore musical based on the life of the twins, Chang & Eng, was directed by Ekachai Uekrongtham and written by Ming Wong, with music by Ken Low. Chang & Eng premiered in 1997 and has since been performed around Asia, starring Robin Goh as Chang Bunker, Sing Seng Kwang as Eng Bunker, and Selena Tan as their mother, Nok. Subsequent productions starred Edmund Toh as Chang Bunker and RJ Rosales as Eng Bunker.

- The best-selling and multiple-award-winning 2000 novel Chang and Eng by Darin Strauss was based on the life of the famous Bunker twins. The film rights to the novel were purchased by award-winning filmmaking team Gary Oldman and Douglas Urbanski. Oldman is currently working on the screenplay and will also direct.[15]

- I Dream of Chang and Eng, a play by noted Bay Area playwright Philip Kan Gotanda that is based on the lives of the Bunker Twins, was produced in workshop form at UC Berkeley and was produced on their main stage in the spring of 2011.[16]

Descendants

Chang and Eng Bunker fathered a total of 21 children, and their descendants now number more than 1,500.[17] Many of their descendants continue to reside in the vicinity of Mount Airy, and descendants of both brothers continue to hold joint reunions. Two hundred descendants reunited in Mount Airy in July 2011 for the twins' 200th birthday and for the descendants' 22nd annual reunion.[18]

Prominent descendants include:

- United States Air Force Major General Caleb V. Haynes was a grandson of Chang Bunker through his daughter Margaret Elizabeth "Lizzie" Bunker.

- General Haynes's son, Vance Haynes, earned a doctorate in geosciences, performed foundational fieldwork at Sandia Cave to determine the timeline of human migration through North America, and served as professor at several universities.

- Alex Sink, former Chief Financial Officer of Florida, is a great-granddaughter of Chang Bunker and was the Democratic nominee in the 2010 Florida gubernatorial election.[19]

- Eng's grandson through his daughter Rosella, George F. Ashby, was President of the Union Pacific Railroad in the 1940s.[20][21]

- Chang's son, Christopher Wren Bunker, built Haystack Farm, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.[22][23]

- Composer Caroline Shaw is a great-great-granddaughter of Chang Bunker and won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2013.[24]

Other prominent conjoined twins

- Millie and Christine McCoy

- Giacomo and Giovanni Battista Tocci

- Daisy and Violet Hilton

- Ronnie and Donnie Galyon

- Lori and George Schappell

- Patrick and Benjamin Binder

- Ladan and Laleh Bijani

- Abby and Brittany Hensel

- Joseph and Luka Banda

References

- 1 2 Traywick, Darryl (1979). "Bunker, Eng and Chang". NCpedia. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Eng and Chang Bunker (1811-1874)". North Carolina History Project. John Locke Foundation. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Iola (January 1, 2001). "Eng Bunker". Entertainers. Find a Grave. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ Iola (May 14, 2002). "Chang Bunker". Entertainers. Find a Grave. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Conjoined Twins". University of Maryland Medical Center. January 8, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Chang and Eng, the Siamese Twins". Calisota Online. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Eng and Chang Bunker". Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ↑ Young, Stephen B. (2003). "Book Review: Two Yankee Diplomats In 1830's Siam by Edmund Roberts and W. S. W. Ruschenberger; edited with an introduction by Michael Smithies and published by Orchid Press". Journal of the Siam Society. 91. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

Ruschenberger reports that the two Siamese Twins — Sam and Eng — were widely known in Bangkok after their departure for the United States, but significantly for their failure to send home remittances to their mother.

- ↑ UNC Univ. Libraries, Southern Historical Collection no. 03761

- 1 2 "Chang and Eng's Grave". roadsideamerica.com. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- 1 2 Chichester, Page. "Reader Favorites: Eng & Chang Bunker: A Hyphenated Life". December 1, 1995. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- 1 2

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Chang and Eng". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. This source confirms the wives' dispute, but strongly diverges on the number of children and says nothing about the household arrangements.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Chang and Eng". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. This source confirms the wives' dispute, but strongly diverges on the number of children and says nothing about the household arrangements. - ↑ Susan Harlan (14 July 2015). "Skin deep: macabre Mütter Museum to open exhibit examining our largest organ". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ Twain, Mark. "The Siamese Twins". The Siamese Twins, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ↑ Whirling upstream in Hollywood: Douglas Urbanski

- ↑ "Philip Kan Gotanda's I Dream of Chang and Eng". San Francisco Chronicle. March 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Together Forever". National Geographic Magazine

- ↑ "Siamese twins descendants hold 22nd annual reunion". Mount Airy News. July 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Twins' great-granddaughter seeks a different kind of fame". St. Petersburg Times. June 11, 2006.

- ↑ Wood, Deborah Shelton (March 25, 2009). "Union Pacific RR President, George F Ashby". Surry – Family History & Genealogy Message Board. Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (2006) [1989]. Union Pacific: Volume II, 1894-1969. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 437. ISBN 0816644608. OCLC 276175222.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Drucilla G. Haley and Jerry L. Cross (April 1981). "Haystack Farm" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- ↑ "Caroline Shaw, the Pulitzer girl". L'Uomo Vogue. November 1, 2013.

- Chang, Iris (2003). The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. Viking. pp. 27–28, 81. ISBN 0-670-03123-2.

- Adapted from the Internet Encyclopedia article, "Chang and Eng Bunker" www.internet-encyclopedia.org – Chang and Eng Bunker 8 July, 2003

Further reading

- Wallace, Amy; Wallace, Irving (1978). The Two: The Story of the Original Siamese Twins. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22627-4.

- Wu, Cynthia (2012). Chang and Eng reconnected : the original Siamese twins in American culture. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781439908686. OCLC 777654628.

- Collins, David R. (1994). Eng & Chang: The Original Siamese Twins. Silver Burdett Press. ISBN 0-382-24719-1. Hardcover ISBN 0-87518-602-5.

- Strauss, Darin (2000). Chang and Eng: A Novel. Dutton. ISBN 0-452-28109-1. Hardcover ISBN 0-525-94512-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Eng and Chang Bunker Digital Project at UNC-Chapel Hill

- Watercolor of the twins and short biography

- Papers of the twins in the archives of the University of North Carolina

- Biography from Wilkesboro.com – copy archived in 2013

- A Hyphenated Life – detailed story in Blue Ridge Country Magazine

- Together Forever – National Geographic Magazine