Chaparral Cars

Chaparral Cars was a pioneering American automobile racing team and race car developer that engineered, built, and raced cars from 1963 through 1970. Founded in 1962 by American Formula One racers Hap Sharp and Jim Hall, it was named after the roadrunner, a fast-running ground cuckoo known in Spanish as a chaparral.

Background

Troutman and Barnes were builders of the original Chaparral race cars (later referred to as Chaparral 1). Jim Hall purchased two Chaparral 1s to race. When Hall and Sharp began building their own cars, they asked Troutman and Barnes if they could continue to use the Chaparral name. That is why the Hall/Sharp cars are all named Chaparral 2s (models 2A through 2J for sports cars/CanAm cars, and the 2K which was the 1979–1982 Indycar). Despite winning the Indianapolis 500 in 1980, they left motor racing in 1982. Chaparral cars also featured in the SCCA/CASC Can-Am series and Endurance racing.

Jim Hall was a leader in the innovation and design of spoilers, wings, and ground effects. A high point was the 1966 2E Can-Am car. The 2J CanAm "sucker car" was the first "ground-effects" car.

The development of the Chaparral chronicles the key changes in race cars in the 1960s and 1970s in both aerodynamics and tires. Hall's training as an engineer taught him to approach problems in a methodical manner and his access to the engineering team at Chevrolet as well as at Firestone changed aerodynamics and race car handling from an art to empirical science. The embryonic data acquisition systems created by the GM research and development group aided these efforts. An interview with Hall by Paul Haney illustrates many of these developments.[1]

Models

1

In 1957, Hall raced the front-engined Chaparral (retroactively called the "Chaparral 1") through 1962, bought from Troutman and Barnes (like the Scarab, the Chaparral 1 cars were built in California by Troutman and Barnes). Hall and Hap Sharp extensively modified their Chaparral, and eventually decided to build their own car. They obtained permission from Trouman and Barnes to use the Chaparral name, which is why all of Hall's cars are called Chaparral 2s.

2

The first Chaparral 2-series was designed and built to compete in the United States Road Racing Championship and other sports car races of the time, particularly the West Coast Pro Series races that were held each fall. Hall had significant "under the table" assistance from GM, including engineering and technical support in the development of the car and its automatic transmission (this is evidenced by the similarity between the Chevy Corvette GS-II "research and development" car and the Chaparral 2A through 2C models).

First raced in late 1963, the Chaparral 2 developed into a dominant car in the CanAm series in 1966 and 1967. Designed for the 200 mile races of the CanAm series, it was also a winner in longer endurance races. In 1965 it shocked the sportscar world by winning the 12 Hours of Sebring in a pouring rain storm, on one of the roughest tracks in North America.

The Chaparral 2 featured the innovative use of fiberglass as a chassis material. The Chaparral 2C had a conventional aluminum chassis.

It is very difficult to identify all iterations of the car as new ideas were being tested continually.

- The 2A is the car as originally raced, featuring a very conventional sharp edge to cut through the air. It also featured a concave tail reminiscent of the theories of Wunibald Kamm. The first aerodynamic appendages began to appear on the 2A almost immediately to cure an issue with the front end being very light at speed with a consequent impact on steering accuracy and driver confidence.

- As the car evolved, it grew and changed shape. Most call these 2Bs, as raced through the end of 1965.

- The 2C was the next car with the innovative in-car adjustable rear wing. The integrated spoiler-wing was designed to lie flat for low drag on the straights and tip up under braking through the corners. This was a direct benefit of the clutchless semi-automatic transmission which kept the driver's left foot free to operate the wing mechanism. The 2C was based on a Chevrolet designed aluminum chassis and was a smaller car in every dimension than the 2B. Without the natural non-resonant damping of the fiberglass chassis, Hall nicknamed it the EBJ — "eye ball jiggler".

Alongside the development of aerodynamics was Hall's development of race tires. Jim Hall owned Rattlesnake Raceway adjacent to his race shop; the proximity allowed him to participate in much of Firestone's race tire development.

A two-article series in Car and Driver magazine featured Hall's design theories. The article turns speculation about vehicle handling into applied physics. Hall's theories were the precursor to the elaborate data collection and management of current racing teams.

The 2D was the first closed cockpit variant of the 2-series, designed for endurance racing in 1966. It won at 1000 km Nürburgring in 1966 with Phil Hill and Joakim Bonnier driving. It also competed in the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans, withdrawing after 111 laps. The Chaparral 2D was equipped with a 327 cubic inch displacement (5.3 liter) aluminum alloy Chevrolet engine producing 420 horsepower, and the car weighed only 924 kg.

The 2E was based on the Chevrolet designed aluminum 2C chassis and presented Hall's most advanced aerodynamic theories to the racing world in the 1966. The 2E established the paradigm for virtually all racing cars built since.[2] It was startling in appearance, with its radiators moved from the traditional location in the nose to two ducted pods on either side of the cockpit and a large wing mounted several feet above the rear of the car on struts. The wing was the opposite of an aircraft wing in that it generated down-force instead of lift and was attached directly to the rear suspension uprights, loading the tires for extra adhesion while cornering. A ducted nose channeled air from the front of the car up, creating extra down-force as well. By depressing a floor pedal that was in the position of a clutch pedal in other cars, Hall was able to feather, or flatten out, the negative angle of the wing when down-force was not needed, such as on a straight section of the track, to reduce drag and increase top speed. In addition, an interconnected air dam closed off the nose ducting for streamlining as well. When the pedal was released, the front ducting and wing returned to their full down-force position. Until they were banned many sports racing cars, as well as Formula One cars, had wings on tall struts, although many were not as well executed as Hall's. The resulting accidents from their failures caused movable wings mounted on the suspension, as well as movable aerodynamic devices, to be outlawed.

The 2E scored only one win, at the 1966 Laguna Seca Raceway Can-Am with Hill driving. Hall stuck to an aluminum 5.3 liter Chevrolet engine in his lightweight racer, while the other teams were using 6 to 7 liter iron engines, trading weight for power.

The 2E was a crowd favorite and remains Hall's favorite car.

In the 2F Hall applied the aerodynamic advances of the aluminum 2E to the older fiberglass chassis closed-cockpit 2D for the 1967 racing season. A movable wing mounted on struts loaded the rear suspension while an air dam kept the front end planted. The radiators were moved to positions next to the cockpit.[3] An aluminum 7 liter rat motor replaced the 5.3 liter engine of the 2D. While always extremely fast, the extra power of the larger engine was too much for the automatic transmission to handle and it broke with regularity. After solving the transmission problems, the 2F scored its only win on 30 July 1967 in the BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch with Hill and Mike Spence driving.[3] After this race, the FIA changed its rules, outlawing not only the 2F, but also the Ford GT40 Mk.IV (winner at Le Mans that year) and the Ferrari 330 P3/4 and 365 P4 (winner at Daytona, second at Le Mans).[3]

As with the 2D, the 2F raced wearing Texas license plates.

The 1967 2G was a development of the 2E. It featured wider tires, and a 427 aluminum Chevrolet engine. While on par with its competitors in terms of power, the lightweight 2C chassis was stretched to the limit and it was only Hall's driving skill that kept the car competitive. For the 1968 Can-Am series, still larger tires were added to increase grip.

Hall's racing career was effectively ended in a severe crash at the Stardust Grand Prix Can-Am race when he rear ended the slow moving McLaren of Lothar Motschenbacher, although he did drive in the 1970 Trans-Am Series while fielding a team of Camaro Trans-Am cars.

Never one to be complacent, Hall noted that the increasing down-force also created enormous drag. Seeking a competitive edge, the 2H was built in 1969 as the replacement for the 2G to minimize drag, rather than maximize down-force. However, the anticipated gains in speed were more than offset by the reduced cornering speeds and the car was consistently slower than anticipated.

A failure, it eventually was fitted with a huge wing.

2J

The most unusual Chaparral was the 2J. On the chassis' sides bottom edges were articulated plastic skirts that sealed against the ground (a technology that would later appear in Formula One). At the rear of the 2J were housed two fans (sourced from a military tank engine) driven by a single two stroke twin cylinder engine.[4] The car had a "skirt" made of Lexan extending to the ground on both sides, laterally on the back of the car, and laterally from just aft of the front wheels. It was integrated with the suspension system so the bottom of the skirt would maintain a distance of one inch from the ground regardless of G forces or anomalies in the road surface, thereby providing a zone within which the fans could create a partial vacuum which would provide a downforce on the order of 1.25–1.50 G of the car fully loaded (fuel, oil, coolant). This gave the car tremendous gripping power and enabled greater maneuverability at all speeds. Since it created the same levels of low pressure under the car at all speeds, down-force did not decrease at lower speeds. With other aerodynamic devices, down-force decreases as the car slows down or achieves too much of a slip angle, both of which were not problems for the "sucker car".

The 2J competed in the Can-Am series and qualified at least two seconds quicker than the next fastest car, but was not a success as it was plagued with mechanical problems. It ran for only one racing season, in 1970, after which it was outlawed by the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA). Although originally approved by the SCCA, they succumbed to pressure from other teams, McLaren in particular, who argued that the fans constituted "movable aerodynamic devices", outlawed by the international sanctioning body, the FIA, a rule first applied against the 2E's adjustable wing. There were also complaints from other drivers saying that whenever they drove behind it the fans would throw stones at their cars. McLaren argued that if the 2J were not outlawed, it would likely kill the Can-Am series by totally dominating it — something McLaren had been doing since 1967.[5] A similar suction fan was used in Formula One eight years later on the Brabham BT46B, which won the 1978 Swedish Grand Prix, but Brabham reverted to the non-fan BT46 soon afterwards due to complaints from other teams that the car violated the rules. The car was found to be within technical specifications allowing the victory to remain.

2K

The 2K was a Formula One-inspired ground effect Indy car designed by Briton John Barnard. Debuting in 1979 with driver Al Unser Sr., it went on to win six races in 27 starts over three seasons. Its greatest success came in 1980, when Johnny Rutherford won both the Indy 500 and the CART championship.

Indy car team

1970s

Chaparral started fielding Indy cars in 1978 with Al Unser driving the No. 2 First National City Traveler's Checks Lola T500-Cosworth DFX. Unser then managed to win the 1978 Indianapolis 500. Later in the season Unser added wins at the California 500 at Ontario Motor Speedway and the Schafer's 500 at Pocono International Raceway, as of 2013 this remains the only time a driver has won the Fuzzy's Premium Vodka Triple Crown. Despite the three wins Unser lost the championship to Tom Sneva (who failed to win a race). With the formation of CART Hall decided to field a car for Unser in that series. Unser now drove the No. 2 Pennzoil Lola T500-Cosworth DFX. At the 1979 Indianapolis 500 Hall, along with fellow CART boardmen Roger Penske, Pat Patrick, Teddy Mayer, Ted Field, and Robert Fletcher were not allowed to compete in the race due to the race being part of the USAC National Championship. At the same Hall was going to introduce the Chaparral 2K-Cosworth DFX. A lawsuit occurred and the six car owners were allowed to field their cars. In the race Unser lead for 89 of the 200 laps. But on lap 105 an engine fire broke out and Unser's bid for a second consecutive, and fourth overall, win was halted. Unser later won the season-ending Miller High Life 150 at Phoenix International Raceway. Unser finished fifth in the CART standing and was ineligible for USAC points.

1980s

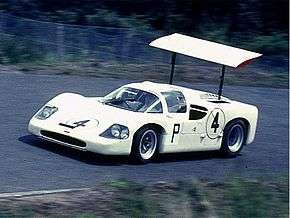

By 1980 Unser had left the team due to disagreements with Hall, and Johnny Rutherford took over driving duties. The only change to the car was that the 2K was now numbered four. Rutherford won five races that season, including the 1980 Indianapolis 500, along with the Datsun Twin 200 at Ontario Motor Speedway, the Red Roof Inn 150 at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course; the Norton 200 at Michigan International Speedway, and the Tony Bettenhausen 200 at the Wisconsin State Fair Park Speedway. Rutherford went on to win the 1980 IndyCar season and CRL championships. In 1981 Rutherford returned with the No. 1 Pennzoil Chaparral 2K-Cosworth DFX. Rutherford pulled off a win in the season-opening Kraco Car Stereos 150 at Phoenix International Raceway. The rest of the season proved to be inconsistent as Rutherford dropped to fifth in points. The team also competed in the opening round of the USAC Gold Crown season, the 1981 Indianapolis 500, Rutherford led for three laps early on but fuel pump issues ended the team's day after only 25 laps. By the 1982 IndyCar season the 2K was getting outdated and the best result for the car was a fourth place finish at the Miller High Life 150 at Phoenix International Raceway. After four races Rutherfoed was ranked 18th in points. By the time the Norton Michigan 500 at Michigan International Speedway came around the team was using a March 82C-Cosworth DFX purchased from Bob Fletcher Racing. Rutherford's results managed to improve as he took his season best finish of third at the AirCal 500K at Riverside International Raceway. Rutherford went on to finish 12th in points. The team also competed at the USAC Gold Crown season finale, the 1982 Indianapolis 500, where Rutherford started 12th and finished 8th.

1990s

In the 1991 CART season Hall returned to Indy cars in conjunction with VDS Racing, with the team being called Hall-VDS Racing with John Andretti driving the No. 4 Pennzoil Z-7 Lola T91/00-Ilmor-Chevrolet Indy V8. The team managed to get a victory in their debut, the Gold Coast IndyCar Grand Prix on the Surfers Paradise Street Circuit. The team also got a second place finish at the Miller Genuine Draft 200 at the Milwaukee Mile. Also, at the 1991 Indianapolis 500 Andretti got a fifth place finish. At the end of the season Andretti was ranked a career-best eighth in points. In the 1992 CART season Andretti drove the No. 8 Pennzoil Z-7 Lola T92/00-Ilmor-Chevrolet Indy V8 for the team. However, Andretti's best finish came at the Pioneer Electronics 200 at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course where he came in fourth place. At the end of the year Andretti finished eighth in points again. He then left the team at the end of the season to compete in the NHRA Winston Drag Racing Series for Jack Clark. So in the 1993 CART season the team fielded Teo Fabi in the No. 8 Pennzoil Lola T93/00-Ilmor-Chevrolet Indy V8. Fabi's best finish was fourth, at the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach on his way to an 11th place finish in points. In the 1994 CART season Fabi drove the No. 11 Pennzoil Reynard 94i-Ilmor D. Fabi's best results that season were a pair of fourth place finishes at the Marlboro 500 at Michigan International Speedway and the Texaco/Havoline 200 at Road America. Fabi went on to end the season ranked ninth in points. At the end of the season he left to drive for Forsythe Racing. For the 1995 CART season VDS dropped out of the venture and the team became known as Hall Racing and rookie Gil de Ferran was signed on to pilot the No. 8 Pennzoil Reynard 95i-Ilmor-Mercedes-Benz IC108. In four of the first six races de Ferran managed to qualify in the top-10. Although he only scored two points during that time. His season soon turned around starting with a pole position at the Budweiser Grand Prix of Cleveland at Cleveland Burke Lakefront Airport where he was leading with five laps to go when he collided with the lapped car of Scott Pruett taking him out of the race. De Ferran avenged this later in the season when he won the season-ending Toyota Monterey Grand Prix at Laguna Seca Raceway. He finished 14th in points and also won the Jim Trueman PPG IndyCar World Series Rookie of the Year Award. For the 1996 IndyCar season de Ferran returned to drive the No. 8 Pennzoil Reynard 96i-Honda Indy V8. De Ferran qualified on the pole at the 1996 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach. H also won the Medic Drug Grand Prix of Cleveland and finished sixth in the final points standings. Despite the recent success Hall closed up the Indy car team for good and de Ferran drove for Walker Racing in the 1997 CART season. Hall ended up getting 13 wins and 2 championships in USAC and CART sanctioned Indy car races.

Museum

In 2005, a wing of the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas was dedicated to the permanent display of the remaining Chaparral cars and the history of their development by Abilene, TX native Jim Hall. To aid in keeping these cars in an optimal state of performance, live runnings are performed on a semi-regular basis at the museum grounds.

Tributes

- The 2005 Monterey Historic Automobile Races honored Chaparrals as the featured marque. Hall's Chaparral 2A had won the Monterey Sports Car Championships at Laguna Seca Raceway in 1964.[6]

- In the 2009 Monterey Sports Car Championships, Gil de Ferran painted his Acura ARX-02a to resemble a Chaparral in tribute to Jim Hall, for whose team de Ferran drove in his first two seasons in CART, and also to commemorate de Ferran's final professional race. An exhibition race featuring the Acura and three Chaparrals was held that Friday, and Hall performed a demonstration lap shortly before the race.

References

- ↑ Haney, Paul (November 21, 2001). "Jim Hall Interview". Inside Racing Technology. insideracingtechnology.com. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ↑ Jeanes, William (February 1, 2007). "2007 Chapparal 2E". Winding Road Magazine, Issue 17. NextAutos.com. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Bissett, Mark. "'67 Spa 1000km: Chaparral 2F". primotipo.com. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Sports Car Graphic No. 5 "Chevrolet's Ground-Effects Car" by Burge Hulett

- ↑ CHAPARRAL — Complete History of Jim Hall's Chaparral Race Cars 1961–1970, by Richard Falconer and Doug Nye, 1992 Motorbooks

- ↑ iDesign Studios (2007-09-03). "Auto Racing Classics – Hall's Chaparrals – Racing Record". Sandcastle V.I. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

External links

- Official Website

- The Chaparral Files

- Fluid Mechanics

- Vic Elford and the Vacuum Cleaner (Chaparral 2J)

- Tribute to Chaparral — a compendium of links to Chaparral references