Churchill Falls Generating Station

| Churchill Falls Generating Station | |

|---|---|

| |

Location of Churchill Falls Generating Station in Canada Newfoundland and Labrador | |

| Location |

Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada |

| Coordinates | 53°31′43.45″N 63°57′57.15″W / 53.5287361°N 63.9658750°WCoordinates: 53°31′43.45″N 63°57′57.15″W / 53.5287361°N 63.9658750°W |

| Construction began | 1967 |

| Opening date | 1974 |

| Construction cost | 946 million CAD |

| Owner(s) | CFLCo |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | 88 rock-filled dikes |

| Impounds | Churchill River |

| Length | 64 km (40 mi) |

| Dam volume | 2,200,000 m3 (2,900,000 cu yd) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates |

Smallwood Reservoir Ossokmanuan Reservoir |

| Total capacity | 32.64 km3 (1.153×1012 cu ft) |

| Catchment area | 71,750 km2 (27,700 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 6,988 km2 (2,698 sq mi) |

| Power station | |

| Operator(s) | CFLCo |

| Commission date | 1971-74 |

| Hydraulic head | 312.4 m (1,025 ft) |

| Turbines | 11 |

| Installed capacity | 5,428 MW |

| Annual generation | 35,000 GWh (130,000 TJ) |

|

Website www | |

The Churchill Falls Generating Station is a hydroelectric power station located on the Churchill River in Newfoundland and Labrador. The underground power station can generate 5,428 MW, which makes it the second-largest in Canada, after the Robert-Bourassa generating station. The generating station was commissioned between 1971 and 1974. The facility is owned and operated by the Churchill Falls Labrador Corporation Limited (CFLCo), a joint venture between Nalcor Energy (65.8%) and Hydro-Québec (34.2%).

Geography

.jpg)

The Innu were early travellers to the site. To them, it was known as Patses-che-wan, "the narrow pass where the waters drop".[1]

In 1915, the Quebec Streams Commission sent engineer Wilfred Thibaudeau survey the Labrador Plateau, then a part of Quebec. Thibodeau was impressed by the site and engineered a channel scheme which could be used to divert the water from the river before it arrived at the falls. The scheme would use the natural capacity of the basin, thereby eliminating the need for the construction of massive dams.[1]

Newfoundland obtained jurisdiction over Labrador in a 1927 ruling of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In 1947, Commander G.H. Desbarats, under the direction of the Newfoundland Government, completed a preliminary survey that confirmed Thibaudeau's findings. However, development did not proceed due to the inhospitable terrain, the severe climatic conditions, the geographic remoteness, the long distance transmission requirement and the lack of markets for such a large block of power.

History

Early planning

In August, 1949, Joey Smallwood, Premier of Newfoundland, had the opportunity to see Churchill Falls for the first time and it became his obsession to develop the hydroelectric potential of the falls.

Smallwood, who was well known in the British capital, travelled to London in the fall of 1952 to promote investment in Canada's newest province. His pitch was well received by the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who later introduces Edmund Leopold de Rothschild, of the N M Rothschild & Sons investment bank.[1][2]

In 1953 British Newfoundland Development Corporation (Brinco) was formed by the Rothschilds and six partners: two paper companies: Bowater and Anglo-Newfoundland; a manufacturer, English Electric; and mining concerns Rio Tinto, Anglo American and Frobisher.[3] The new company aimed to do extensive exploration of the untapped water and mineral resources of the area. With the development of the iron ore mines in western Labrador and Schefferville and the construction of the Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway in 1954, development of Hamilton Falls — as they were then known — as a power source, became feasible.

Brinco's efforts were facilitated by a Principal Agreement signed with the Newfoundland government granting it the right to explore the province's natural resource potential. In return, Brinco committed to invest $5 million over 20 years on exploration and to pay an 8% royalty on net profits before taxes.[1]

Recruiting investors and customers

Among the issues facing the would-be developers in the 1950s, the recruitment of customers for the output of the plant was high on the list of concerns. A few options were considered by Brinco officials. As early as 1955, Brinco's CEO, Bill Southam calls on Robert J. Beaumont, president of the Shawinigan Water & Power Company (SWP), Quebec's largest power company at the time, to push the project to Premier Maurice Duplessis and to government-owned utility Hydro-Québec. Brinco's offers were summarily dismissed by the Union Nationale premier, who had already committed towards Hydro-Québec building its own power projects in Quebec, such as the Bersimis-1 and Bersimis-2 generating stations, rather than importing electricity.[1][4]

SWP was an early supporter of the project. As early as 1954, the company's planners did consulting work on the project for Brinco. But SWP had other reasons. Facing a rapidly increasing demand, and having been denied the possibility of developing the Bersimis River in 1951, its officials were eager to find new energy resources to meet rapidly increasing demand.[5] This is why Shawinigan Engineering, a subsidiary of SWP, agreed to become a partner in the entreprise.[6] In 1958, SWP was granted a 20% share of the venture, called Hamilton Falls Power Corporation, for a C$2.25 million investment.[7]

As was the long-standing practice in Quebec's power generation business,[8] Brinco tried to recruit "anchor" customers for the large amount of power they would add to supply. Its officials made pitches to large industrial power users, but aluminium companies Alcan, Alcoa and British Aluminium all rejected the possibility of building smelters in Labrador. The United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority decided against building an uranium enrichment plant in the area.[1]

The second solution was selling the power to other jurisdictions. But, exporting power to Ontario and the Northeastern United States also had its set of problems. Ontario Hydro felt that generating electricity in-province using nuclear power would be cheaper than building costly long-distance transmission lines from Labrador to Ontario through Quebec. Brinco and its power subsidiary were also wary of the political implications such a line would have in Quebec. On top of all these problems, selling the power in the U.S. was complicated by the National Energy Board stance against long-term power export contracts[1]

Contract talks

The death of Maurice Duplessis, in September 1959, raised hopes of a change of attitude in Quebec. Brinco's representatives met with the new Quebec premier, Paul Sauvé, in the fall of 1959. However, the talks stalled as Sauvé died early in 1960.[9]

The government of Quebec considered the inland watershed of Labrador to be part of their province and fought a long but losing legal battle to prevent granting the territory to Newfoundland at the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

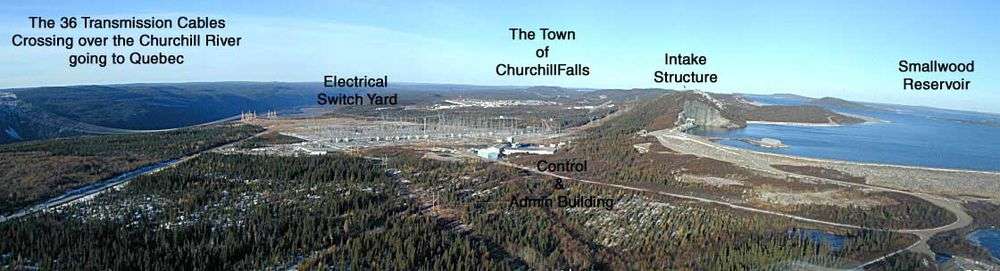

Construction

After years of planning, the project was officially started on July 17, 1967. The machine hall of the power facility at Churchill Falls was hollowed out of solid rock, close to 1,000 ft (300 m) underground. Its final proportions are huge: in height it equals a 15-storey building, its length is three times that of a Canadian football field. When completed, it housed 11 generating units, with a combined capacity of 5,428 MW (7,279,000 hp). Water is contained by a reservoir created not by a single large dam, but by a series of 88 dikes that have a total length of 64 km (40 mi). At the time, the project was the largest civil engineering project ever undertaken in North America.[10]

Once all the dikes were in place, it provided a vast storage area which later became known as Smallwood Reservoir. This reservoir covers 2,200 sq mi (5,700 km2) and provides storage area for more than 1,000,000,000,000 cu ft (2.8×1010 m3) of water.

The drainage area for the Churchill River includes much of western and central Labrador. Ossokmanuan Reservoir which was originally developed as part of the Twin Falls Power System also drains into this system. Churchill River's natural drainage area covers over 23,300 sq mi (60,000 km2). Once Orma and Sail lakes' outlets were diked, it added another 4,400 sq mi (11,000 km2) of drainage for a total of 27,700 sq mi (72,000 km2). This makes the drainage area larger than the Republic of Ireland. Studies showed this drainage area collected 410 mm (16 in) of rainfall plus 391 cm (154 in) of snowfall annually equalling 12.5 cu mi (52 km3) of water per year; more than enough to meet the project's needs. Construction came to fruition on December 6, 1971, when Churchill Falls went into full-time production.

The generating station is owned by the Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Ltd. — whose shareholders are Nalcor (65.8%) and Hydro-Québec (34.2%) —[11] and operated by the Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro company.

Legal challenge and controversy

The division of profits from the sale of electricity generated at the plant has proven to be a very sensitive political issue in Newfoundland and Labrador, with many considering the share accorded to Hydro-Québec "an immense and unconscionable windfall."[12]

The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has twice challenged the contract in court, with both challenges failing.[13] Additionally, in 1984 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a proposal by Newfoundland to divert water away from the falls was illegal.[11]

According to former Premier Brian Tobin, as Labrador only borders Quebec, when an agreement was being negotiated to sell the power generated at Churchill Falls, the power either had to be sold to an entity within Quebec or it had to pass through Quebec. The government of Quebec refused to allow power to be transferred through Quebec and would only accept a contract in which the power was sold to Quebec.[14] Because of this monopsony situation, Hydro-Québec received very favourable terms on the power sale contract. The contract was negotiated to run for a 65-year timespan, running until the year 2041, and according to former Newfoundland Premier Danny Williams, Hydro-Québec reaps profits from the Upper Churchill contract of approximately $1.7 billion per year, while Newfoundland and Labrador receives $63 million a year.[15]

According to long-time Hydro-Québec critic Claude Garcia, former president of Standard Life (Canada) and author of a recent assessment of the utility commissioned by the Montreal Economic Institute, if Hydro-Québec had to pay market prices for the low-cost power it got from the Churchill Falls project in Labrador, the 2007 profit would be an estimated 75 per cent lower. Newfoundland and Labrador will be able to renegotiate the project in 2041, when the contract expires.[16]

Aboriginal rights

The Churchill Falls hydroelectric plant development was undertaken in the absence of any agreement with the aboriginal Innu people of Labrador. The construction involved the flooding of over 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) of traditional hunting and trapping lands. A recent agreement signed between the government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Innu offered the Labrador Innu hunting rights within 34,000 square kilometres of land, plus $2 million annually in compensation for flooding.

Project facts

- Churchill Falls power plant is the second largest hydroelectric plant in North America, with an installed capacity of 5,428 MW (7,279,000 hp).

- Churchill Falls was, at the time of its construction, the largest underground power station in the world. (The Robert-Bourassa power station in Quebec currently holds the record, both for installed capacity and volume of the main underground hall).

- The powerhouse is 972 ft (296 m) long, up to 81 ft (25 m) wide and 154 ft (47 m) high from the bottom to the top. The height would be equivalent to a 15-storey building or almost as long as three Canadian football fields 990 ft (300 m) and is hollowed from solid granite. To strengthen walls and ceiling, more than 11,000 rock bolts (steel rods 15 to 25 ft (5 to 8 m) long) were used in the three major chambers.

- To move the 2,300,000 cu yd (1,800,000 m3) of rock that was excavated from the underground caverns, it required 5,000,000 lb (2,300,000 kg). This material was used in roads, building the town site, and as dike material.

- The turbine wheels are cast of stainless steel and weigh 80 short tons (73 t) which is a world record for the largest stainless steel casting ever made.

- During construction, 730,000 short tons (660,000 t) of material, equipment and fuel were moved to the site.

- The natural catchment area for the Churchill River covers over 23,300 sq mi (60,000 km2).

- By diverting the water from the Ossokmanuan Reservoir the total catchment area became 27,700 sq mi (72,000 km2).

- Total natural drop of the water starting at Ashuanipi Lake and ending at Lake Melville is 1,735 ft (529 m). As a comparison, the water starting 30 km (19 mi) upriver until it enters the power plant drops over 1,000 ft (300 m).

- There is no big dam associated with this hydropower plant. There are 88 dikes to contain the reservoir, the longest is 6.1 km (3.8 mi)and the highest is 36 m (118 ft). The total length of all dikes is 64 km (40 mi) and contains 26,000,000 cu yd (20,000,000 m3) of embankment material.

- After five years of non-stop field work by approximately 6,300 workers and costing $950,000,000 (1970) construction culminated on December 6, 1971 when the first two generating units began delivering power, five months and three weeks ahead of schedule.

- Currently Churchill Falls makes almost 1% of the world's hydroelectric power.

- Newfoundland and Labrador recently announced a call to develop the Lower Churchill Project. This effort would be made up of a number of small projects including a 2,250 MW (3,020,000 hp) dam at Gull Island, an 824 MW (1,105,000 hp) dam at Muskrat Falls, and a 1,000 MW (1,300,000 hp) upgrade to the existing facility at the Churchill Falls. If completed, these projects would add 4,000 MW (5,400,000 hp) of power production capability, for a total of 9,502 MW (12,742,000 hp) for the entire Churchill River hydroelectric complex.

Specifications and statistics

Power station

| Churchill Falls generating station | |

|---|---|

| Year commissioned: | 1971 |

| Installed capacity: | 5,428 MW (7,279,000 hp) |

| Annual energy output: | 35,000 GWh (130,000 TJ) |

| Number of turbines: | 11 |

| Turbine capacity: | 493.5 MW (661,800 hp) |

| Type of turbine: | vertical Francis type, 200 rpm |

| Generators: | 15 kV, 526,315 kV·A |

| Transformers: | 14.75 kV/240 kV, rated at 500 MV·A |

| Net rated head: | 312.4 m (1,025 ft) |

| Maximum tailrace discharge: | 49,000 ft³/s (1,390 m³/s) |

| Powerhouse: | 296 m (971 ft) length, 25 m (82 ft) width, 47 m (154 ft) height, 310 m (1,020 ft) below ground |

| Tailrace tunnels: | 2 × 1,691 m (5,548 ft), 14 m (46 ft) width, 19 m (62 ft) height |

| Penstocks: | 11 × 427 m (1,401 ft) length, 20 ft (6.1 m) diameter |

| Cable shafts: | 06 × 7 ft (2.13 m) diameter, 263 m (863 ft) deep |

| Dikes: | 88; 64.4 km (40.0 mi) total length, 9 m (30 ft) average height, 36 m (118 ft) maximum height |

| Size of reservoir: | 6,988 km2 (2,698 sq mi) |

| Total catchment area: | 71,700 km2 (27,700 sq mi) |

See also

- Lower Churchill Project

- Newfoundland-Labrador fixed link

- Re Upper Churchill Water Rights Reversion Act

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bolduc, André (1982), "Churchill Falls, the dream... and the reality", Forces, Montreal (57-58), pp. 40–42

- ↑ Smith 1975

- ↑ Smith 1975, pp. 17–18

- ↑ Smith 1975, p. 79

- ↑ Bellavance 1994, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Bellavance 1994, pp. 184

- ↑ Smith 1975, p. 151

- ↑ Dales 1957

- ↑ Smith 1975, p. 119

- ↑ James Marsh (2010). "Churchill Falls". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- 1 2 Supreme Court of Canada (1984-05-03). "Reference re Upper Churchill Water Rights Reversion Act, (1984) 1 S.C.R. 297". CanLII. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ↑ Why the Churchill Falls Agreement Must be Re-Negotiated

- ↑ "Churchill Falls deal probed". The Gazette. canada.com. December 20, 2005. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Speaking notes from an address by Brian Tobin". Premier's Address on Churchill Falls to the Empire Club, Toronto. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. November 19, 1996. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ Moore, Lynn (November 30, 2009). "Newfoundland challenges Churchill Falls hydro deal with Quebec". Canwest News Service. Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ Baril, Hélène (4 February 2009). "Privatisation d'Hydro-Québec: Claude Garcia s'explique". La Presse (in French). Montreal. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

Further reading

- Books

- Bellavance, Claude (1994), Shawinigan Water and Power (1898-1963) : Formation et déclin d'un groupe industriel au Québec (in French), Montreal: Boréal, ISBN 2-89052-586-4

- Bolduc, André (2000), Du génie au pouvoir : Robert A. Boyd, à la gouverne d'Hydro-Québec aux années glorieuses (in French), Montreal: Libre Expression, ISBN 2-89111-829-4

- Bolduc, André; Hogue, Clarence; Larouche, Daniel (1989), Québec, l'héritage d'un siècle d'électricité (in French) (3rd ed.), Montreal: Libre Expression, ISBN 2-89111-388-8.

- Côté, Langevin (1972), Heritage of power : the Churchill Falls development from concept to reality, St. John's: Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Limited

- Dales, John H. (1957), Hydroelectricity and Industrial Development Quebec 1898-1940, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

- Meisel, John; Rocher, Guy; Silver, Arthur (1999), Institute for Research on Public Policy, ed., As I recall = Si je me souviens bien : historical perspectives, Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy, ISBN 0-88645-173-6

- Quebec Hydro-Electric Commission; Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Limited (1969-05-12), Power Contract Between the Quebec Hydro-Electric Commission and the Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Limited (PDF), Montreal, retrieved 2009-12-02

- Smith, Philip (1975), Brinco: The story of Churchill Falls, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-8184-7

- Articles

- Churchill, Jason L. (1999), "Pragmatic Federalism: The Politics Behind the 1969 Churchill Falls Contract", Newfoundland Studies, 15 (2), pp. 215–246, ISSN 0823-1737, retrieved 2010-01-30

- Feehan, James (2009), "The Churchill Falls Contract : What Happened and What's to Come?" (PDF), Newfoundland Quarterly, 101 (4), pp. 35–38

- Feehan, James P.; Baker, Melvin (2007), "The Origins of a Coming Crisis: Renewal of the Churchill Falls Contract" (PDF), Dalhousie Law Journal (30), pp. 207–257, retrieved 2010-01-31

External links

- Churchill Falls Hydroelectric project

- Map of project area from Churchill Falls Corporation

- Profile of the Innu people of Labrador

- Hon. Brian Tobin 1996 speech to the Empire Club

- The loophole in the 1969 Hydro-Québec/CFLCo. agreement