Coco Chanel

| Coco Chanel | |

|---|---|

Chanel in 1920 | |

| Born |

Gabrielle Chanel 19 August 1883 Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, France |

| Died |

10 January 1971 (aged 87) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery, Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Fashion designer |

| Parent(s) |

Eugénie Jeanne Devolle Albert Chanel |

| Awards | Neiman Marcus Fashion Award, 1957 |

| Labels | Chanel |

Gabrielle Bonheur "Coco" Chanel (19 August 1883 – 10 January 1971)[1] was a French fashion designer and businesswoman. She was the founder and namesake of the Chanel brand. Along with Paul Poiret, Chanel was credited in the post-World War I era with liberating women from the constraints of the "corseted silhouette" and popularizing a sporty, casual chic as the feminine standard of style. A prolific fashion creator, Chanel extended her influence beyond couture clothing, realising her design aesthetic in jewellery, handbags, and fragrance. Her signature scent, Chanel No. 5, has become an iconic product. She is the only fashion designer listed on Time magazine's list of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century.[2]

Chanel was known for her lifelong determination, ambition, and energy which she applied to her professional and social life. She achieved both financial success as a businesswoman and catapulted to social prominence in French high society, thanks to the connections she made through her work. These included many artists and craftspeople to whom she became a patron.

Her social connections appeared to encourage a highly conservative personal outlook. Rumors arose about Chanel's activities during the German occupation of France in World War II, and she was criticised for being too comfortable with the Germans but never thoroughly investigated.[3] After several years in Switzerland after the war, she returned to Paris and revived her fashion house. In 2011, Hal Vaughan published a book on Chanel based on newly declassified documents of that era, revealing that she had collaborated with Germans in intelligence activities. One plan in late 1943 was for her to carry an SS separate peace overture to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to end the war.[4]

Early life

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born in 1883 to an unmarried mother, Eugénie Jeanne Devolle—known as Jeanne—a laundrywoman, in the charity hospital run by the Sisters of Providence (a poorhouse) in Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, France.[5][6] She was Jeanne's second child with Albert Chanel; the first, Julia, was born less than a year earlier.[6] Albert Chanel was an itinerant street vendor who peddled work clothes and undergarments,[7] living a nomadic life, traveling to and from market towns. The family resided in rundown lodgings. In 1884, he married Jeanne Devolle,[8] persuaded to do so by her family who had "united, effectively, to pay Albert to marry her."[9] At birth, Chanel's name was entered into the official registry as "Chasnel". Jeanne was too unwell to attend the registration, and Albert was registered as "travelling".[5] With both parents absent, the infant's last name was misspelled, probably due to a clerical error. The couple had five children who survived—two boys and three girls—who lived crowded into a one-room lodging in the town of Brive-la-Gaillarde.[6]

When Gabrielle was 12,[10][11] her mother died of bronchitis[10] at the age of 32.[12] Her father sent his two sons out to work as farm laborers and sent his three daughters to the Corrèze, in central France, to the convent of Aubazine, which ran an orphanage. Its religious order, the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Mary, was "founded to care for the poor and rejected, including running homes for abandoned and orphaned girls".[13] It was a stark, frugal life, demanding strict discipline. At age eighteen, Chanel, too old to remain at Aubazine, went to live in a boarding house set aside for Catholic girls in the town of Moulins.[14]

Later in her life, Chanel would retell the story of her childhood somewhat differently; she would often include more glamorous accounts, which were generally untrue.[6] She said that when her mother died, her father sailed for America to seek his fortune, and she was sent to live with two aunts. She also claimed to have been born a decade later than 1883 and that her mother had died when she was much younger than 12.[15]

Personal life and early career

Aspirations for a stage career

Having learned the art of sewing during her six years at Aubazine, Chanel was able to find employment as a seamstress. When not plying her needle, she sang in a cabaret frequented by cavalry officers. Chanel made her stage debut singing at a café-concert (a popular entertainment venue of the era) in a Moulins pavilion, "La Rotonde". She was among other girls dubbed poseuses, the performers who entertained the crowd between star turns. The money earned was what they managed to accumulate when the plate was passed among the audience in appreciation of their performance. It was at this time that Gabrielle acquired the name "Coco", possibly based on two popular songs with which she became identified, "Ko Ko Ri Ko", and "Qui qu'a vu Coco", or it was an allusion to the French word for kept woman, cocotte.[16] As a cafe entertainer, Chanel radiated a juvenile allure that tantalized the military habitués of the cabaret.[17]

In 1906, Chanel was working in the spa resort town of Vichy. Vichy boasted a profusion of concert halls, theatres and cafes where she hoped to achieve success as a performer. Chanel's youth and physical charms impressed those for whom she auditioned, but her singing voice was marginal and she failed to find stage work.[18] Obliged to find employment, she took work at the "Grande Grille", where as a donneuse d'eau she was one of the females whose job was to dispense glasses of the purportedly curative mineral water for which Vichy was renowned.[19] When the Vichy season ended, Chanel returned to Moulins, and her former haunt "La Rotonde". She now realised that a serious stage career was not in her future.[20]

Balsan and Capel

At Moulins, Chanel met the young French ex-cavalry officer and the wealthy textile heir Étienne Balsan. At the age of twenty-three, Chanel became Balsan's mistress, supplanting the courtesan Émilienne d’Alençon as his new favorite.[21] For the next three years, she lived with him in his château Royallieu near Compiègne, an area known for its wooded equestrian paths and the hunting life.[22] It was a lifestyle of self-indulgence; Balsan's wealth and leisure allowed the cultivation of a social set who reveled in partying and the gratification of human appetites, with all the implied accompanying decadence; Balsan lavished Chanel with the beauties of "the rich life"—diamonds, dresses, and pearls. Biographer Justine Picardie, in her 2010 study Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life (Harper Collins), suggests that the fashion designer's nephew, André Palasse, supposedly the only child of her sister Julia-Berthe who had committed suicide, was Chanel's child by Balsan.

In 1908, Chanel began an affair with one of Balsan's friends, Captain Arthur Edward 'Boy' Capel.[23] In later years, Chanel reminisced of this time in her life: "two gentlemen were outbidding for my hot little body."[24] Capel, a wealthy member of the English upper class, installed Chanel in an apartment in Paris.[25] and financed her first shops. It is said that Capel's sartorial style influenced the conception of the Chanel look. The bottle design for Chanel No. 5 had two probable origins, both attributable to the sophisticated design sensibilities of Capel. It is believed Chanel adapted the rectangular, beveled lines of the Charvet toiletry bottles he carried in his leather traveling case[26] or she adapted the design of the whiskey decanter Capel used; she so much admired it that she wished to reproduce it in "exquisite, expensive, delicate glass".[27] The couple spent time together at fashionable resorts such as Deauville, but despite Chanel's hopes that they would settle together, Capel was never faithful to her.[28] Their affair lasted nine years. Even after Capel married an English aristocrat, Lady Diana Wyndham in 1918, he did not completely break off with Chanel. He died in a car accident on 21 December 1919.[29][30] A roadside memorial at the site of Capel's accident is said to have been commissioned by Chanel.[31] Twenty-five years after the event, Chanel, then residing in Switzerland, confided to her friend, Paul Morand: "His death was a terrible blow to me. In losing Capel, I lost everything. What followed was not a life of happiness, I have to say."[32]

Chanel had begun designing hats while living with Balsan, initially as a diversion that evolved into a commercial enterprise. She became a licensed milliner in 1910 and opened a boutique at 21 rue Cambon, Paris, named Chanel Modes.[33] As this location already housed an established clothing business, Chanel sold only her millinery creations at this address. Chanel's millinery career bloomed once theatre actress Gabrielle Dorziat wore her hats in Fernand Nozière's play Bel Ami in 1912. Subsequently, Dorziat modelled Chanel's hats again in photographs published in Les Modes.[33]

Deauville and Biarritz

In 1913, Chanel opened a boutique in Deauville, financed by Arthur Capel, where she introduced deluxe casual clothes suitable for leisure and sport. The fashions were constructed from humble fabrics such as jersey and tricot, at the time primarily used for men's underwear.[33] The location was a prime one, in the center of town on a fashionable street. Here Chanel sold hats, jackets, sweaters, and the marinière, the sailor blouse. Chanel had the dedicated support of two family members, her sister Antoinette, and her paternal aunt Adrienne, who was of a similar age.[34] Adrienne and Antoinette were recruited to model Chanel's designs; on a daily basis the two women paraded through the town and on its boardwalks, advertising the Chanel creations.[35]

Chanel, determined to re-create the success she had enjoyed in Deauville, opened an establishment in Biarritz in 1915. Biarritz, situated on the Côte Basque, in proximity to wealthy Spanish clients, had neutral status during World War I, allowing it to become the playground for the moneyed and those exiled from their native countries by the hostilities.[36] The Biarritz shop was installed not as a storefront, but in a villa opposite the casino. After one year of operation, the business proved to be so lucrative that in 1916 Chanel was able to reimburse Capel his original investment. This was her sole decision; she did not consult with Capel.[37] It was in Biarritz that Chanel made the acquaintance of an expatriate aristocrat, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia. They had a romantic interlude, and maintained a close association for many years afterward.[38] By 1919, Chanel was registered as a couturière and established her maison de couture at 31 rue Cambon, Paris.[33]

Established couturière

In 1918, Chanel purchased the entire building at 31 rue Cambon, which was situated in one of the most fashionable districts of Paris. In 1921, she opened what may be considered an early incarnation of the fashion boutique, featuring clothing, hats, and accessories, later expanded to offer jewellery and fragrance. By 1927, Chanel owned five properties on the rue Cambon, encompassing buildings numbered 23 to 31.[39]

In the spring of 1920 (approximately May), Chanel was introduced to the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky by Sergei Diaghilev, impresario of the Ballets Russes.[40] During the summer, Chanel discovered that the Stravinsky family was seeking a place to live, having left the Soviet Union after the war. She invited them to her new home, "Bel Respiro," in the Paris suburb of Garches, until they could find a more suitable residence.[40] They arrived at "Bel Respiro" during the second week of September[40] and remained until May 1921.[41] Chanel also guaranteed the new (1920) Ballets Russes production of Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) against financial loss with an anonymous gift to Diaghilev, said to be 300,000 francs.[42] In addition to turning out her couture collections, Chanel threw her prodigious energies into designing dance costumes for the cutting-edge Ballets Russes. Between the years 1923-1937, she collaborated on productions choreographed by Diaghilev and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, notably Le Train bleu, a dance-opera; Orphée and Oedipe Roi.[43]

In 1922, at the Longchamps races, Théophile Bader, founder of the Paris Galeries Lafayette, introduced Chanel to businessman Pierre Wertheimer. Bader was interested in inaugurating the sale of the Chanel No. 5 fragrance in his department store.[44] In 1924, Chanel made an agreement with the Wertheimer brothers, Pierre and Paul, directors since 1917 of the eminent perfume and cosmetics house Bourgeois. They created a corporate entity, "Parfums Chanel," and the Wertheimers agreed to provide full financing for production, marketing and distribution of Chanel No. 5. The Wertheimers would receive seventy percent of the profits, and Théophile Bader a twenty percent share. For ten percent of the stock, Chanel licensed her name to Parfums Chanel and withdrew from involvement in all business operations.[45] Displeased with the arrangement, Chanel worked for more than twenty years to gain full control of Parfums Chanel.[44][45] She said that Pierre Wertheimer was "the bandit who screwed me".[46]

One of Chanel's longest enduring associations was with Misia Sert, a notable member of the bohemian elite in Paris and wife of Spanish painter José-Maria Sert. It is said that theirs was an immediate bond of like souls, and Misia was attracted to Chanel by "her genius, lethal wit, sarcasm and maniacal destructiveness, which intrigued and appalled everyone".[47] Both women were convent schooled, and maintained a friendship of shared interests and confidences. They also shared drug use. By 1935, Chanel had become a habitual drug user, injecting herself with morphine on a daily basis, a habit she maintained until the end of her life.[48] According to Chandler Burr's The Emperor of Scent, Luca Turin related an apocryphal story in circulation that Chanel was "called Coco because she threw the most fabulous cocaine parties in Paris".[49]

The writer Colette, who moved in the same social circles as Chanel, provided a whimsical description of Chanel at work in her atelier, which appeared in "Prisons et Paradis" (1932). "If every human face bears a resemblance to some animal, then Mademoiselle Chanel is a small black bull. That tuft of curly black hair, the attribute of bull-calves, falls over her brow all the way to the eyelids and dances with every maneuver of her head."[50]

Associations with British aristocrats

In 1923, Vera Bate Lombardi, (born Sarah Gertrude Arkwright),[51] reputedly the illegitimate daughter of the Marquess of Cambridge,[51] afforded Chanel entry into the highest levels of British aristocracy. It was an elite group of associations revolving around such figures as politician Winston Churchill, aristocrats such as the Duke of Westminster, and royals such as Edward, Prince of Wales. In Monte Carlo in 1923, at age forty, Chanel was introduced by Lombardi to the vastly wealthy Duke of Westminster, Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, known to his intimates as "Bendor". The Duke of Westminster lavished Chanel with extravagant jewels, costly art, and a home in London's prestigious Mayfair district. His affair with Chanel lasted ten years.[52]

The Duke, an outspoken anti-Semite, intensified Chanel's inherent antipathy toward Jews. He shared with her an expressed homophobia. In 1946, Chanel was quoted by her friend and confidant, Paul Morand:

- "Homosexuals? … I have seen young women ruined by these awful queers: drugs, divorce, scandal. They will use any means to destroy a competitor and to wreak vengeance on a woman. The queers want to be women—but they are lousy women. They are charming!"[53]

Coinciding with her introduction to the Duke, was her introduction, again through Lombardi, to Lombardi's cousin, the Prince of Wales, Edward VIII. The Prince allegedly became smitten with Chanel and pursued her in spite of her involvement with the Duke of Westminster. Gossip had it that he visited Chanel in her apartment and requested that she call him "David", a privilege reserved only for his closest friends and family. Years later, Diana Vreeland, editor of Vogue, would insist that "the passionate, focused and fiercely independent Chanel, a virtual tour de force," and the Prince "had a great romantic moment together".[54]

In 1927, the Duke of Westminster gave Chanel a parcel of land he had purchased in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the French Riviera. Chanel built her villa here, which she called La Pausa[55] ("restful pause"), hiring the architect Robert Streitz. Streitz's concept for the staircase and patio contained design elements inspired by Aubazine, the orphanage in which Chanel spent her youth.[56][57] When asked why she did not marry the Duke of Westminster, she is supposed to have said: "There have been several Duchesses of Westminster. There is only one Chanel."[58]

Designing for film

In 1921, while in Monte Carlo Chanel became acquainted with Samuel Goldwyn. She was introduced through a mutual friend, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, cousin to the last czar of Russia, Nicolas II. Goldwyn offered Chanel a tantalizing proposition. For the sum of a million dollars (approximately seventy-five million in twenty-first century valuation), he would bring her to Hollywood twice a year to design costumes for MGM stars. Chanel accepted the offer. Accompanying her on her first trip to Hollywood was her friend Misia Sert.

En route to California from New York, traveling in a white train car luxuriously outfitted for her use, Chanel was interviewed by Colliers magazine in 1932. She said that she had agreed to go to Hollywood to "see what the pictures have to offer me and what I have to offer the pictures."[59] Chanel designed the clothing worn on screen by Gloria Swanson, in Tonight or Never (1931), and for Ina Claire in The Greeks Had a Word for Them (1932). Both Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich became private clients.[60]

Her experience with American movie making left Chanel with a dislike for the Hollywood film business and distaste for the film world's culture, which she denounced as "infantile".[61] Chanel's verdict was that "Hollywood is the capital of bad taste … and it is vulgar."[62] Ultimately, her design aesthetic did not translate well to film. The New Yorker speculated that Chanel had left Hollywood because "they told her her dresses weren't sensational enough. She made a lady look like a lady. Hollywood wants a lady to look like two ladies."[63] Chanel went on to design the costumes for several French films, including Jean Renoir's 1939 film La Règle du jeu, in which she was credited as La Maison Chanel. Chanel introduced the left-wing Renoir to Luchino Visconti, aware that the shy Italian hoped to work in film. Renoir was favorably impressed by Visconti and brought him in to work on his next film project.[64]

Significant liaisons: Reverdy and Iribe

Chanel was the mistress of some of the most influential men of her time, but she never married. She had significant relationships with the poet Pierre Reverdy and the illustrator and designer Paul Iribe. After her romance with Reverdy ended in 1926, they maintained a friendship that lasted some forty years.[65] It is postulated that the legendary maxims attributed to Chanel and published in periodicals were crafted under the mentorship of Reverdy—a collaborative effort.

"A review of her correspondence reveals a complete contradiction between the clumsiness of Chanel the letter writer and the talent of Chanel as a composer of maxims … After correcting the handful of aphorisms that Chanel wrote about her métier, Reverdy added to this collection of “Chanelisms” a series of thoughts of a more general nature, some touching on life and taste, others on allure and love."[66]

Her involvement with Iribe was a deep one until his sudden death in 1935. Iribe and Chanel shared the same reactionary politics, Chanel financing Iribe's monthly, ultra-nationalist and anti-republican newsletter, Le Témoin, which encouraged an irrational fear of foreigners and preached anti-Semitism.[67][68] In 1936, one year after Le Témoin stopped publication, Chanel veered to the opposite end of the ideological continuum by financing Pierre Lestringuez's radical left-wing magazine Futur.[69]

Rivalry with Schiaparelli

The Chanel couture was a lucrative business enterprise, by 1935 employing 4,000 people.[60] As the 1930s progressed, Chanel's place on the throne of haute couture was threatened. The boyish look and the short skirts of the 1920s flapper seemed to disappear overnight. Chanel's designs for film stars in Hollywood were not successful and had not aggrandized her reputation as expected. More significantly, Chanel's star had been eclipsed by her premier rival, the designer Elsa Schiaparelli. Schiaparelli's innovative design, replete with playful references to Surrealism, was garnering critical acclaim and generating enthusiasm in the fashion world. Feeling she was losing her avant-garde edge, Chanel collaborated with Jean Cocteau on his theatre piece Oedipe Rex. The costumes she designed were mocked and critically lambasted: "Wrapped in bandages the actors looked like ambulant mummies or victims of some terrible accident."[70]

World War II

In 1939, at the beginning of World War II, Chanel closed her shops, maintaining her apartment situated above the couture house at 31 Rue de Cambon. She claimed that it was not a time for fashion;[36] as a result of her action, 4,000 female employees lost their jobs.[71] Her biographer Vaughan suggests that Chanel used the outbreak of war as an opportunity to retaliate against those workers who, lobbying for fair wages and work hours, had closed her business operation during a general labor strike in France in 1936. In closing her couture house, Chanel made a definitive statement of her political views. Her dislike of Jews, reportedly inculcated by her convent years and sharpened by her association with society elites, had solidified her beliefs. She shared with many of her circle a conviction that Jews were a threat to Europe because of the Bolshevik government in the Soviet Union.[71]

During the German occupation, Chanel resided at the Hotel Ritz. It was noteworthy as the preferred place of residence for upper-echelon German military staff. Her romantic liaison with Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, a German officer who had been an operative in military intelligence since 1920,[72] eased her arrangements at the Ritz.[73]

Battle for control of Parfums Chanel

World War II, specifically the Nazi seizure of all Jewish-owned property and business enterprises, provided Chanel with the opportunity to gain the full monetary fortune generated by Parfums Chanel and its most profitable product, Chanel No. 5. The directors of Parfums Chanel, the Wertheimers, were Jewish. Chanel used her position as an "Aryan" to petition German officials to legalize her claim to sole ownership.

- On 5 May 1941, she wrote to the government administrator charged with ruling on the disposition of Jewish financial assets. Her grounds for proprietary ownership were based on the claim that Parfums Chanel "is still the property of Jews" and had been legally "abandoned" by the owners.[74][75]

"I have," she wrote, "an indisputable right of priority … the profits that I have received from my creations since the foundation of this business ... are disproportionate ... [and] you can help to repair in part the prejudices I have suffered in the course of these seventeen years."[76]

Chanel was not aware that the Wertheimers, anticipating the forthcoming Nazi mandates against Jews had, in May 1940, legally turned control of Parfums Chanel over to Félix Amiot, a Christian French businessman and industrialist. At war's end, Amiot returned "Parfums Chanel" to the hands of the Wertheimers.[74][75]

During the period directly following the end of World War II, the business world watched with interest and some apprehension the ongoing legal wrestle for control of Parfums Chanel. Interested parties in the proceedings were cognizant that Chanel's Nazi affiliations during wartime, if made public knowledge, would seriously threaten the reputation and status of the Chanel brand. Forbes magazine summarized the dilemma faced by the Wertheimers: [it is Pierre Wertheimer's worry] how "a legal fight might illuminate Chanel's wartime activities and wreck her image—and his business."[77]

Chanel hired René de Chambrun, Vichy France Prime Minister Pierre Laval's son-in-law, as her lawyer to sue Wertheimer.[78] Ultimately, the Wertheimers and Chanel came to a mutual accommodation, renegotiating the original 1924 contract. On 17 May 1947, Chanel received wartime profits from the sale of Chanel No. 5, in an amount equivalent to some nine million dollars in twenty-first century valuation. Her future share would be two percent of all Chanel No. 5 sales worldwide. The financial benefit to her would be enormous. Her earnings were projected at $25 million a year, making her at the time one of the richest women in the world. In addition, Pierre Wertheimer agreed to an unusual stipulation proposed by Chanel herself. Wertheimer agreed to pay all of Chanel's living expenses—from the trivial to the large—for the rest of her life.[79][80]

Activity as Nazi agent

Declassified, archival documents unearthed by biographer Hal Vaughan reveal that the French Préfecture de Police had a document on Chanel in which she was described as "Couturier and perfumer. Pseudonym: Westminster. Agent reference: F 7124. Signalled as suspect in the file" (Pseudonyme: Westminster. Indicatif d'agent: F 7124. Signalée comme suspecte au fichier).[81][82] For Vaughan, this was a piece of revelatory information linking Chanel to German intelligence operations. Anti-Nazi activist Serge Klarsfeld declared, "It is not because Chanel had a spy number that she was necessarily personally implicated. Some informers had numbers without being aware of it." ("Ce n'est pas parce que Coco Chanel avait un numéro d'espion qu'elle était nécessairement impliquée personnellement. Certains indicateurs avaient des numéros sans le savoir").[83]

Vaughan establishes that Chanel committed herself to the German cause as early as 1941 and worked for General Walter Schellenberg, chief of SS intelligence.[3] At the end of the war, Schellenberg was tried by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal, and sentenced to six years' imprisonment for war crimes. He was released in 1951 owing to incurable liver disease and took refuge in Italy. Chanel paid for Schellenberg's medical care and living expenses, financially supported his wife and family, and paid for Schellenberg's funeral upon his death in 1952.[84]

Operation Modellhut

In 1943, Chanel traveled to Berlin with her lover, Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, an Abwehr spy, to meet with SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler to formulate strategy.[3] In late 1943 or early 1944, Chanel and her SS master, Schellenberg, devised a plan to get a request to Britain to consider a separate peace to be negotiated by the SS. When interrogated by British intelligence at war's end, Schellenberg maintained that Chanel was "a person who knew Churchill sufficiently to undertake political negotiations with him".[85] For this mission, named Operation Modellhut ("Model Hat"), they also recruited Vera Bate Lombardi. Count Joseph von Ledebur-Wicheln, a Nazi agent who defected to the British Secret Service in 1944, recalled a meeting he had with Dincklage in early 1943, in which the baron had suggested including Lombardi as a courier. Dincklage purportedly said, "The Abwehr had first to bring to France a young Italian woman [Lombardi] Coco Chanel was attached to because of her lesbian vices…"[86]

Unaware of the machinations of Schellenberg and Chanel, Lombardi was led to believe that the forthcoming journey to Spain would be a business trip exploring the potential for establishing the Chanel couture in Madrid. Lombardi acted as intermediary, delivering a letter written by Chanel to Winston Churchill, to be forwarded to him via the British embassy in Madrid.[87] Schellenberg's SS liaison officer, Captain Walter Kutschmann, acted as bagman, "told to deliver a large sum of money to Chanel in Madrid".[88] Ultimately, the mission proved a failure for the Germans. British intelligence files reveal that the plan collapsed after Lombardi, on arrival in Madrid, proceeded to denounce Chanel and others to the British embassy as Nazi spies.[89]

Protection from prosecution

In September 1944, Chanel was called in to be interrogated by the Free French Purge Committee, the épuration. The committee had no documented evidence of her collaboration activity and was obliged to release her. According to Chanel's grand-niece, Gabrielle Palasse Labrunie, when Chanel returned home she said, "Churchill had me freed".[90]

The extent of Churchill's intervention for Chanel after the war became a subject of gossip and speculation. Some historians claimed that people worried that, if Chanel were forced to testify about her own activities at trial, she would expose the pro-Nazi sympathies and activities of certain top-level British officials, members of the society elite, and the royal family. Vaughan writes that some claim that Churchill instructed Duff Cooper, British ambassador to the French provisional government, to protect Chanel.[91]

Requested to appear in Paris before investigators in 1949, Chanel left her retreat in Switzerland to confront testimony given against her at the war crime trial of Baron Louis de Vaufreland, a French traitor and highly placed German intelligence agent. Chanel denied all the accusations. She offered the presiding judge, Leclercq, a character reference: "I could arrange for a declaration to come from Mr. Duff Cooper."[92]

Chanel's friend and biographer Marcel Haedrich said of her wartime interaction with the Nazi regime: "If one took seriously the few disclosures that Mademoiselle Chanel allowed herself to make about those black years of the occupation, one's teeth would be set on edge."[93]

Controversy

When Vaughan's book was published in August 2011, his disclosure of the contents of recently de-classified military intelligence documents, generated considerable controversy about Chanel's activities. The House of Chanel issued a statement, portions of which were published in myriad media outlets. Chanel corporate "refuted the claim" (of espionage), while acknowledging that company officials had read only media excerpts of the book.[94]

The Chanel group stated, "What's certain is that she had a relationship with a German aristocrat during the War. Clearly it wasn't the best period to have a love story with a German even if Baron von Dincklage was English by his mother and she (Chanel) knew him before the War."[95]

In an interview given to the Associated Press, author Vaughan discussed the unexpected turn of his research.

"I was looking for something else and I come across this document saying 'Chanel is a Nazi agent'…Then I really started hunting through all of the archives, in the United States, in London, in Berlin and in Rome and I come across not one, but 20, 30, 40 absolutely solid archival materials on Chanel and her lover, Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage, who was a professional Abwehr spy."[96]

Vaughan also addressed the discomfort many felt with the revelations provided in his book: "A lot of people in this world don't want the iconic figure of Gabrielle Coco Chanel, one of France's great cultural idols, destroyed. This is definitely something that a lot of people would have preferred to put aside, to forget, to just go on selling Chanel scarves and jewellery."[94]

Post-war life and career

In 1945, Chanel moved to Switzerland, where she lived for several years, part of the time with Dincklage. In 1953 she sold her villa La Pausa on the French Riviera to the publisher and translator Emery Reves. Five rooms from La Pausa have been replicated at the Dallas Museum of Art, to house the Reves' art collection as well as pieces of furniture belonging to Chanel.[57]

Unlike the pre-war era, when women reigned as the premier couturiers, Christian Dior achieved success in 1947 with his "New Look", and a cadre of male designers achieved recognition: Dior, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Robert Piguet, and Jacques Fath. Chanel was convinced that women would ultimately rebel against the aesthetic favored by the male couturiers, what she called "illogical" design: the "waist cinchers, padded bras, heavy skirts, and stiffened jackets".[97]

At more than 70 years old, after having her couture house closed for 15 years, she felt the time was right for her to re-enter the fashion world.[97] The revival of her couture house in 1954 was fully financed by Chanel's opponent in the perfume battle, Pierre Wertheimer.[98] Her new collection was not received well by Parisians, who felt her reputation had been tainted by her wartime association with the Nazis. But, her return to couture was applauded by the British and Americans, who became her faithful customers.

Last years

According to Edmonde Charles-Roux,[99] Chanel had become tyrannical and extremely lonely late in life. In her last years she was sometimes accompanied by Jacques Chazot and her confidante Lilou Marquand. A faithful friend was also the Brazilian Aimée de Heeren, who lived in Paris four months a year at the nearby Hôtel Meurice. The former rivals shared happy memories of times with the Duke of Westminster. They frequently walked together around central Paris.[100]

Death

As 1971 began, Chanel was 87 years old, tired, and ailing. She carried out her usual routine of preparing the spring catalogue. She had gone for a long drive the afternoon of Saturday, 9 January. Soon after, feeling ill, she went to bed early.[101] She died on Sunday, 10 January 1971, at the Hotel Ritz, where she had resided for more than 30 years.[102] Her funeral was held at the Église de la Madeleine; her fashion models occupied the first seats during the ceremony and her coffin was covered with white flowers—camellias, gardenias, orchids, azaleas and a few red roses. She went out in real Chanel style, announcing: "You see, this is how you die."[103]

Her grave is located in the Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery, Lausanne, Switzerland.[104]

Most of her estate was inherited by her nephew André Palasse, who lived in Switzerland, and his two daughters, who lived in Paris.[78]

Legacy as designer

As early as 1915, Harper's Bazaar raved over Chanel's designs: "The woman who hasn't at least one Chanel is hopelessly out of fashion … This season the name Chanel is on the lips of every buyer."[105] Chanel's ascendancy was the official deathblow to the corseted female silhouette. The frills, fuss, and constraints endured by earlier generations of women were now passé; under her influence—gone were the "aigrettes, long hair, hobble skirts".[106] Her design aesthetic redefined the fashionable woman for the post World War I era. The Chanel trademark was a look of youthful ease, a liberated physicality, and unencumbered sportive confidence.

The horse culture and penchant for hunting so passionately pursued by the elites, especially the British, fired Chanel's imagination. Her own enthusiastic indulgence in the sporting life led to clothing designs informed by those activities. From her excursions on water with the yachting world, she appropriated the clothing associated with nautical pursuits: the horizontal striped shirt, bell-bottom pants, crewneck sweaters, and espadrille shoes—all traditionally worn by sailors and fishermen.[107]

Jersey fabric

Chanel's initial triumph was the innovative use of jersey fabric, a machine knit material manufactured for her by the firm Rodier.[108] This fabric was traditionally relegated to the manufacture of undergarments. Chanel's early wool jersey traveling suit consisted of a cardigan jacket, and pleated skirt, paired with a low-belted pullover top. This ensemble, worn with low-heeled shoes, became the casual look in expensive women's wear.[109] Prior to this, jersey tended to be used only in hosiery and for sportswear for tennis, golf and the beach. Considered too "ordinary" to be used in couture, it was also disliked by designers because the knit made it difficult to handle compared to woven fabrics.

Chanel's introduction of jersey to high-fashion worked well for two reasons. First, the war had caused a shortage of other materials and second, women were desiring more simple and practical clothes. Her fluid jersey suits and dresses were created for practicality and allowed free movement. This was greatly appreciated at the time because women were working for the war effort as nurses, in civil service and in factories. Their work involved physical activity and they had to ride trains, buses and bicycles to get to work.[110] They desired outfits that did not give way easily and could be put on without the help of servants.[111]

Slavic influence

Designers such as Paul Poiret and Fortuny introduced ethnic references into haute couture in the 1900s and early 1910s.[112] Chanel continued this trend with Slav-inspired designs in the early 1920s. The beading and embroidery on her garments at this time was exclusively executed by Kitmir, an embroidery house founded by an exiled Russian aristocrat, the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, the sister of her erstwhile lover, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich.[113][114] Kitmir's fusion of oriental stitching with stylised folk motifs was highlighted in Chanel's early collections.[114] One 1922 evening dress came with a matching embroidered 'babushka' headscarf.[114] In addition to the headscarf, Chanel clothing from this period featured square-neck, long belted blouses alluding to Russian muzhiks (peasant) attire known as the roubachka.[115] Evening designs were often embroidered with sparkling crystal and black jet embroidery.[116]

The Chanel Suit

The Chanel tweed suit was built for comfort and practicality. It consisted of a jacket and skirt in supple and light wool or mohair tweed and a blouse and jacket lining in jersey or silk. Chanel did not stiffen the material or use shoulder pads, as was common in contemporary fashion. She cut the jackets on the straight grain, without adding bust darts. This allowed for quick and easy movement. She designed the neckline to leave the neck comfortably free and added functional pockets designed to hold things. For a higher level of comfort, the skirt had a grosgrain stay around the waist, instead of a belt. More importantly, meticulous attention was placed on detail during fittings. Measurements were taken of a customer in a standing position with arms folded at shoulder height. Chanel conducted tests with models, having them walk around, step up to a platform as if climbing stairs of an imaginary bus, and bend as if getting into a low-slung sports car. Chanel wanted to make sure women could do all of these things while wearing her suit, without accidentally exposing parts of their body they wanted covered. Each client would have repeated adjustments until their suit was comfortable enough for them to perform daily activities with comfort and ease.[117]

Camellia

The camellia had an established association used in Alexandre Dumas' literary work, La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady of the Camellias). Its heroine and her story had resonated for Chanel since her youth. The flower was associated with the courtesan, who would wear a camellia to advertise her availability.[118] The camellia came to be identified with The House of Chanel; the designer first used it in 1933 as a decorative element on a white-trimmed black suit.[60]

Little black dress

After the jersey suit, the concept of the little black dress is often cited as a Chanel contribution to the fashion lexicon; it is a style still worn to this day. In 1912–13, the actress Suzanne Orlandi was one of the first women to wear a Chanel little black dress, in velvet with a white collar.[119] Chanel herself claimed that in 1920, while observing an audience at the opera, she vowed that she would dress all women in black.[120]

In 1926, the American edition of Vogue published an image of a Chanel little black dress with long sleeves, dubbing it the garçonne (little boy look).[60] Vogue predicted that such a simple yet chic design would become a virtual uniform for women of taste, famously comparing its basic lines to the ubiquitous and no less widely accessible Ford automobile.[121][122] The spare look generated widespread criticism from male journalists, who complained: "no more bosom, no more stomach, no more rump ... Feminine fashion of this moment in the 20th century will be baptized lop off everything."[123] The popularity of the little black dress can be attributed in part to the timing of its introduction. The 1930s was a period of the Great Depression Era, when women needed affordable fashion. Chanel boasted that she had enabled the non-wealthy to "walk around like millionaires".[124] [125] Chanel started making little black dresses in wool or chenille for the day and in satin, crêpe or velvet for the evening.[126]

Chanel proclaimed "I imposed black; it's still going strong today, for black wipes out everything else around."[120]

Jewellery

Chanel introduced a line of jewellery that was a conceptual innovation, as her design and materials incorporated both simulated and fine gem stones. This was revolutionary in an era when jewellery was strictly categorized into either fine or costume jewellery. Her inspirations were global, often inspired by design traditions of the Orient and Egypt. Wealthy clients who did not wish to display their costly jewellery in public could wear Chanel creations to impress others.[127]

In 1933, designer Paul Iribe collaborated with Chanel in the creation of extravagant jewellery pieces commissioned by the International Guild of Diamond Merchants. The collection, executed exclusively in diamonds and platinum, was exhibited for public viewing and drew a large audience; some 3,000 attendees were recorded in a one-month period.[60]

As an antidote for vrais bijoux en toc, the obsession with costly, fine jewels,[60] Chanel turned costume jewellery into a coveted accessory—especially when worn in grand displays, as she did. Originally inspired by the opulent jewels and pearls given to her by aristocratic lovers, Chanel raided her own jewel vault and partnered with Duke Fulco di Verdura to launch a House of Chanel jewellery line. A white enameled cuff featuring a jeweled Maltese cross was Chanel's personal favourite; it has become an icon of the Verdura Chanel collaboration.[60] The fashionable and wealthy loved the creations and made the line wildly successful. Chanel issued a PR statement: "It's disgusting to walk around with millions around the neck because one happens to be rich. I only like fake jewellery … because it's provocative."[128]

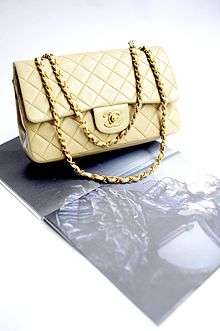

The Chanel bag

In 1929 Chanel offered a handbag inspired by soldier's bags. Its thin shoulder strap allowed the user to have her hands free.[129][130] Following her comeback, Chanel updated the design in February 1955, creating what would become the "2.55" (named for the date of its creation).[129] Whilst details of the classic bag have been reworked, such as the 1980s update by Karl Lagerfeld where the clasp and lock were redesigned to incorporate the crossed C's Chanel logo and leather was interlaced through the shoulder chain, the bag has retained its basic form.[131] In 2005, the Chanel firm released an exact replica of the original 1955 bag to commemorate the 50th anniversary of its creation.[131]

The bag's design was informed by Chanel's convent days and her love of the sporting world. The chain used for the strap echoed the chatelaines worn by the caretakers of the orphanage where Chanel grew up, whilst the burgundy lining referenced the convent uniforms.[131] The quilted outside was influenced by the jackets worn by jockeys,[131] whilst at the same time enhancing the bag's shape and volume.[129]

Suntans

In an outdoor environment of turf and sea, Chanel took in the sun, making suntans not only acceptable, but a symbol denoting a life of privilege and leisure. Historically, identifiable exposure to the sun had been the mark of laborers doomed to a life of unremitting, unsheltered toil. "A milky skin seemed a sure sign of aristocracy." By the mid-1920s, women could be seen lounging on the beach without a hat to shield them from the sun's rays. The Chanel influence made sun bathing fashionable.[132]

Depictions in popular culture

- Theatre

The Broadway musical Coco, with music by André Previn, book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, opened 18 December 1969 and closed 3 October 1970. It is set in 1953–1954 at the time that Chanel was reestablishing her couture house. Chanel was played by Katharine Hepburn for the first eight months, and by Danielle Darrieux for the rest of its run.

- Film

The first film about Chanel was Chanel Solitaire (1981), directed by George Kaczender and starring Marie-France Pisier, Timothy Dalton, and Rutger Hauer.

Coco Chanel (2008) was a television movie starring Shirley MacLaine as a 70-year-old Chanel. Directed by Christian Duguay, the film also starred Barbora Bobuľová as the young Chanel and Olivier Sitruk as Boy Capel.

Coco avant Chanel (Coco Before Chanel) (2009) was a French-language biographical film starring Audrey Tautou as the young Chanel, with Benoît Poelvoorde as Étienne Balsan and Alessandro Nivola as Boy Capel

Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky (2009) was a French-language film directed by Jan Kounen. Anna Mouglalis played Chanel, and Mads Mikkelsen played Igor Stravinsky. The film was based on the 2002 novel Coco and Igor by Chris Greenhalgh, which concerns a purported affair between Chanel and Stravinsky. It was chosen to close the Cannes Film Festival of 2009.[133]

References

- ↑ "Madamoiselle Chanel: The Perennially Fashionable". Chanel. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ↑ Horton, Ros; Simmons, Sally (2007). Women Who Changed the World. Quercus. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-84724-026-2. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Vaughan, p. xix

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal. Sleeping With the Enemy, Coco Chanel's Secret War. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011: pp. 160-164

- 1 2 Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 14. ISBN 9781905490363.

- 1 2 3 4 Picardie, Justine (5 September 2010). "The Secret Life of Coco Chanel". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Chaney, p. 16

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 16. ISBN 9781905490363.

- 1 2 Chaney, Lisa (6 Oct 2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141972992. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Wilson, Frances (1 Oct 2010). "Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life by Justine Picardie: review". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 18. ISBN 9781905490363.

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 27. ISBN 9781905490363.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Biog. "Coco Chanel". lifetimetv.co.uk. Lifetime TV. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde. Chanel and Her World, Hachette-Vendome, 1981: pp. 37-38

- ↑ Vaughan 2011.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Hirst, Gwendoline. "Chanel 1883–1971 (Part One)". BA Fashion. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

At this time in 1909, at the age of 26, she became friendly with an Englishman Arthur Capel, nicknamed "Boy", who was one of Etienne [Balsan]'s friends…

- ↑ Wallach, Janet. Chanel: Her style and her life. Nan A. Talese, 1998: p. 19

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 7.

- ↑ Bollon, Patrice (2002) (in French). Esprit d'époque: essai sur l'âme contemporaine et le conformisme naturel de nos sociétés. Le Seuil. p. 57. ISBN 978-2-02-013367-8. "L'adaptation d'un flacon d'eau de toilette pour hommes datant de l'avant-guerre du chemisier Charvet."

- ↑ Mazzeo, Tilar J. The Secret of Chanel No. 5. HarperCollins, 2010: p. 103

- ↑ Hirst, Gwendoline (22 February 2001). "Chanel 1883–1971". BA Education. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ The Times, 24 December 1919, p. 10: "Captain Arthur Capel, who was killed in an automobile crash on Monday, is being buried today".

- ↑ Cokayne, George Edward (1982). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant. X. Gloucester: A. Sutton. p. 773 note (c). ISBN 0-904387-82-8.

- ↑ "Puget-sur-Argens Coco Chanel: le drame de sa vie au bord d'une route varoise" (in French). varmatin.com. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Mackrell, Alice (2005). Art and Fahion. Sterling Publishing. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-7134-8873-9. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- 1 2 Sabatini, Adelia (2010). "The House that Dreams Built". Glass Magazine (2): 66–71. ISSN 2041-6318.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ "Chanel 31 rue Cambon. The History Behind The Facade", Le Grand Mag, retrieved 10 October 2012

- 1 2 3 Walsh (1999), p.318

- ↑ Walsh (1999), p.329.

- ↑ Walsh (1999), p.319 and see his footnote 21.

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal. Sleeping With The Enemy, Coco Chanel's Secret War. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011: p. 31-32

- 1 2 Thomas, Dana. "The Power Behind The Cologne". The New York Times: 24 February 2002. Retrieved 18 July 2012

- 1 2 Mazzeo, p. 95

- ↑ Mazzeo, p. 153.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Burr, Chandler (2002). The Emperor of Scent: A true story of perfume and obsession. Random House Inc. p. 43. ISBN 0-375-75981-6.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- 1 2 "Sarah Vera Gertrude Arkwright Bate Lombardi—Person Page 15929". thePeerage.com. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 41.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Watson, Nanette. "Coco Chanel's Villa La Pausa | Houses with History". Houseswithhistory.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 48–49.

- 1 2 Bretell, Richard R. (1995). The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art.

- ↑ "Coco Chanel Biography". Inoutstar.com. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Mazzeo, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "retrieved August 3, 2012". Vogue.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 62.

- ↑ Madsen, Axel (1991). Chanel: A Woman of Her Own. p. 194.

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 306. ISBN 9781905490363.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 300. ISBN 9781905490363.

- ↑ Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. p. 313. ISBN 9781905490363.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 96.

- 1 2 Vaughan 2011, p. 101.

- ↑ Vaughan, p. 57

- ↑ Vaughan, chapter 11.

- 1 2 Mazzeo, p. 150.

- 1 2 Thomas, Dana. "The Power Behind The Cologne". The New York Times: 24 February 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012

- ↑ Mazzeo, p. 152-53

- ↑ Mazzeo, Tilar J. The Secret of Chanel No. 5, HarperCollins, 2010: p. 175

- 1 2 "Sweet Smell of Perfume". The Lincoln Star. Lincoln, Nebraska. February 28, 1971. p. 72. Retrieved August 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Mazzeo, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Muir, Kate (4 April 2009). "Chanel and the Nazis: what Coco Avant Chanel and other films don't tell you". The Times. London. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Warner, Judith. "Was Coco Chanel a Nazi Agent?". The New York Times.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 140.

- ↑ "Chanel antisémite, tabou médiatique en France ?". Arrêt sur images. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 205–207.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 169.

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal. Sleeping With the Enemy, Coco Chanel's Secret War. Alfred A. Knopf, 2011: p. 163-164

- ↑ Vaughan, p. 169-71

- ↑ Vaughan, p. 174

- ↑ Vaughan, p. 174-75

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 187.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 199.

- ↑ Mazzeo, p. 175.

- 1 2 , 17 August 2011, Retrieved 15 June 2012

- ↑ , Reuters, 16 August 2011, Retrieved 15 June 2012]

- ↑ http://www.latimesblogs.latimes.com, 18 August 2011, Retrieved 16 June 2012

- 1 2 Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Mazzeo, Tilar J. The Secret of Chanel No. 5, HarperCollins, 2010: p. 176–177

- ↑ Edmonde Charles-Roux (op.cit., p. 222).

- ↑ , memories of Aimée de Heeren walking around Paris with Coco Chanel

- ↑ Mazzeo, p. 196.

- ↑ "On This Day: Chanel, the Couturier, Dead in Paris". The New York Times. 11 January 1971. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/childrens-books-site/2016/feb/24/top-10-amazing-facts-you-didnt-know-about-coco-chanel

- ↑ "Cimetière du Bois-de-Vaux". Fodor's Travel Intelligence.

- ↑ Vaughan, p. 14

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 47, 79.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 128, 133. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, pp. 13, 47.

- ↑ Leymarie, Jean (1987). Chanel. New York City: Rizzoli International Publications. p. 57.

- ↑ Wallach, Janet (1998). Chanel: Her Style and Her Life. New York: N. Talese. p. 28.

- ↑ "Introduction to 20th Century Fashion, V&A". Vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ 1922 evening dress embroidered by Kitmir in the Victoria & Albert Museum collections

- 1 2 3 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Fall, 2005) p.39. (for a PDF file showing relevant page, see here ). An image of dress with headscarf in situ may be seen on the Metropolitan database here

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal. "Sleeping With The Enemy, Coco Chanel Secret War". Alfred A. Knopf, 2011: p. 25-26

- ↑ Gautier, Jerome (2011). Chanel: The Vocabulary of Style. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 244.

- ↑ http://www.wsj.com, Jacobs, Laura. "The Enduring Coco Chanel". Wall Street Journal, 19 November 2011, retrieved 6 September 2012

- ↑ Staff writer. "Fashion design for Suzanne Orlandi, Été 1901, by Jeanne Paquin". V&A Search the Collections. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- 1 2 Picardie, Justine (2010). Coco Chanel: the legend and the life. London: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9780061963858.

- ↑ Wollen, Peter. "Cinema/Americanism/the Robot". In Naremore, James; Brantlinger, Patrick. Modernity and Mass Culture. Indiana University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0253206278.

- ↑ English, Bonnie (2013). A Cultural History of Fashion in the 20th and 21st Centuries: From Catwalk to Sidewalk. A&C Black. p. 36. ISBN 9780857851369.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ Pendergast, Tom and Sarah (2004). Fashion, Costume and Culture. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. p. 792.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Wallach, Janet (1998). Chanel: Her Style and Her Life. New York: N. Talese. p. 83.

- ↑ Leymarie, Jean (1987). Chanel. New York City: Rizzoli International Publications. p. 153.

- ↑ Vaughan 2011, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Pedersen, Stephanie (2006). Handbags: What Every Woman Should Know. Cincinnati: David & Charles. p. 68. ISBN 0-7153-2495-0.

- ↑ Wallach, Janet (1999). Chanel: Her Style and Her Life. London: Mitchell Beazley. p. 158. ISBN 1-84000-202-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Kpriss. "Short History of The Famous Chanel 2.55 Bag". Style Frizz. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

Bibliography

- Chaney, Lisa (2011). Chanel: An Intimate Life. London: Fig Tree. ISBN 978-1-905-49036-3.

- Charles-Roux, Edmonde (1981). Chanel and Her World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-78024-3.

- Mazzeo, Tilar J. (2010). The Secret of Chanel No. 5. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-179101-7.

- Vaughan, Hal (2011). Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel's Secret War. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-59263-7.

- Walsh, Stephen (1999). Stravinsky: A Creative Spring. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-41484-3.

Further reading

- Charles-Roux, Edmonde (2005). The World of Coco Chanel: Friends, Fashion, Fame. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51216-6.

- Davis, Mary (December 2006). "Chanel, Stravinsky, and Musical Chic". Fashion Theory. 10 (4): 431–60. doi:10.2752/136270406778664986.

- Fiemeyer, Isabelle (2011). Intimate Chanel. Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-080-30162-8.

- Madsen, Axel (2009). Coco Chanel: A Biography. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 978-1408805817.

- Mazzeo, Tilar J. (2010). The Secret of Chanel No. 5. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-179101-7.

- Morand, Paul (2009). The Allure of Chanel. Pushkin Press. ISBN 978-1-901285-98-7.

- Picardie, Justine (2010). Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-196385-8.

- Simon, Linda (2011). Coco Chanel. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-859-3. (Reviewed in The Montreal Review)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coco Chanel. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Coco Chanel |

- Official Site of Chanel

- Gabrielle Chanel at the Fashion Model Directory

- Coco Chanel in the Art Deco Era

- Lisa Chaney on Coco Chanel on YouTube

- Coco Chanel 1969 interview on YouTube

- Interactive timeline of couture houses and couturier biographies Victoria and Albert Museum