Corwin Amendment

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

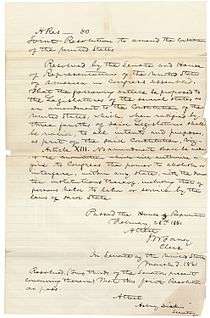

The Corwin Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that would shield "domestic institutions" of the states (which in 1861 included slavery) from the constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress.[1][2] It was passed by the 36th Congress on March 2, 1861, and submitted to the state legislatures for ratification. Senator William H. Seward of New York introduced the amendment in the Senate and Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio introduced it in the House of Representatives. It was one of several measures considered by Congress in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to attract the seceding states back into the Union and in an attempt to entice border slave states to stay.[3][4]

Text

No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.[1][5]

The text refers to slavery with terms such as "domestic institutions" and "persons held to labor or service" and avoids using the word "slavery", following the example set at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which referred to slavery in its draft of the Constitution with comparable descriptions of legal status: "Person held to Service", "the whole Number of free Persons ..., three fifths of all other Persons", "The Migration and Importation of such Persons".[6]

Legislative history

36th Congress

In the Congressional session that began in December 1860, more than 200 resolutions with respect to slavery,[7] including 57 resolutions proposing constitutional amendments,[8] were introduced in Congress. Most represented compromises designed to avert military conflict. Mississippi Democratic Senator Jefferson Davis proposed one that explicitly protected property rights in slaves.[8] A group of House members proposed a national convention to accomplish secession as a "dignified, peaceful, and fair separation" that could settle questions like the equitable distribution of the federal government's assets and rights to navigate the Mississippi River.[9]

On February 27, 1861, the House of Representatives considered the following text of a proposed constitutional amendment:[10]

No amendment of this Constitution, having for its object any interference within the States with the relations between their citizens and those described in second section of the first article of the Constitution as "all other persons," shall originate with any State that does not recognize that relation within its own limits, or shall be valid without the assent of every one of the States composing the Union.

Corwin proposed his own text as a substitute and those who opposed him failed on a vote of 68 to 121. The House then declined to give the resolution the required two-thirds vote, with a tally of 120 to 61, and then of 123 to 71.[10][11] On February 28, 1861, however, the House approved Corwin's version by a vote of 133 to 65.[12] The contentious debate in the House was relieved by abolitionist Republican Owen Lovejoy of Illinois, who questioned the amendment's reach: "Does that include polygamy, the other twin relic of barbarism?" Missouri Democrat John S. Phelps answered: "Does the gentleman desire to know whether he shall be prohibited from committing that crime?"[8]

On March 2, 1861, the United States Senate adopted it, with no changes, on a vote of 24 to 12.[13] Since proposed constitutional amendments require a two-thirds majority, 132 votes were required in the House and 24 in the Senate. The Senators and Representatives from the seven slave states that had already declared their secession from the Union did not vote on the Corwin Amendment.[14] The resolution called for the amendment to be submitted to the state legislatures and to be adopted "when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures."[15] Its supporters believed that the Corwin Amendment had a greater chance of success in the legislatures of the Southern states than would have been the case in state ratifying conventions, since state conventions were being conducted throughout the South at which votes to secede from the Union were successful—just as Congress was considering the Corwin Amendment.

The Corwin Amendment was the second proposed "Thirteenth Amendment" submitted to the states by Congress. The first was the similarly ill-fated Titles of Nobility Amendment in 1810.

Response by Presidents

Out-going President James Buchanan, a Democrat, endorsed the Corwin Amendment by taking the unprecedented step of signing it.[16] His signature on the Congressional joint resolution was unnecessary, as the Supreme Court, in Hollingsworth v. Virginia (1798), ruled that the President has no formal role in the constitutional amendment process.

Abraham Lincoln, in his first inaugural address, said of the Corwin Amendment:[2][17]

I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution—which amendment, however, I have not seen—has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service ... holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.

Just weeks prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Lincoln sent a letter to each state's governor transmitting the proposed amendment,[18] noting that Buchanan had approved it.[19]

Attempted withdrawal of the Corwin Amendment

On February 8, 1864, during the 38th Congress, with the prospects for a Union victory improving, Republican Senator Henry B. Anthony of Rhode Island introduced Senate (Joint) Resolution No. 25[20] to withdraw the Corwin Amendment from further consideration by the state legislatures and to halt the ratification process. That same day, Anthony's joint resolution was referred to the Senate's Committee on the Judiciary. On May 11, 1864, Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull, Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, received the Senate's permission to discharge Senate (Joint) Resolution No. 25 from the Committee, with no further action having been taken on Anthony's joint resolution.[21]

Ratification history

The Corwin Amendment was ratified by:

- Kentucky — April 4, 1861[22][23]

- Ohio — May 13, 1861[24] (Rescinded ratification – March 31, 1864[25])

- Rhode Island — May 31, 1861[22][26]

- Maryland — January 10, 1862[19][27] (Rescinded ratification – April 7, 2014[28])

- Illinois — February 14, 1862[15] (Questionable validity[lower-alpha 1])

The Restored Government of Virginia, consisting mostly of representatives of what would become West Virginia, voted to approve the amendment on February 13, 1862.[22] However, West Virginia did not ratify the amendment after it became a state in 1863.

In 1963, more than a century after the Corwin Amendment was submitted to the state legislatures by the Congress, a joint resolution to ratify it was introduced in the Texas House of Representatives by Dallas Republican Henry Stollenwerck.[30] The joint resolution was referred to the House's Committee on Constitutional Amendments on March 7, 1963, but received no further consideration.[31]

Possible impact if adopted

The Corwin Amendment, when viewed through the lens of the plain meaning rule (literal rule), would have, had it been ratified by the required number of states prior to 1865, made institutionalized slavery immune to the constitutional amendment procedures and to interference by Congress. As a result, the later Reconstruction Amendments (Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth) would not have been permissible, as they abolish or interfere with the domestic institution of the states.

A competing theory, however, suggests that a later amendment conflicting with an already-ratified Corwin Amendment could either explicitly repeal the Corwin Amendment (as the Twenty-first Amendment explicitly repealed the Eighteenth Amendment) or be inferred to have partially or completely repealed any conflicting provisions of an already-adopted Corwin Amendment.[32][33]

See also

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution

- List of proposed amendments to the United States Constitution

- Slavery in the United States

- Peace Conference of 1861

Notes

- ↑ As Congress submitted the amendment to the state legislatures for ratification and Illinois lawmakers were sitting as delegates to a state constitutional convention rather than as members of the legislature when they ratified the amendment, the state's ratification of the Corwin Amendment is of questionable validity.[19][29]

References

- 1 2 "Constitutional Amendments Not Ratified". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2013-11-21.

- 1 2 Walter, Michael (2003). "Ghost Amendment: The Thirteenth Amendment That Never Was". Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. Oxford University Press. p. 609.

- ↑ Foner, 2010, p. 158

- ↑ The Corwin Amendment appears officially in Volume 12 of the Statutes at Large at page 251.

- ↑ David Waldstreicher, Slavery's Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (NY: Hill & Wang, 2009), "Prologue: Meaningful Silences", 3-10, 98-9, 113. "Madison succeeded only in getting through a semantic change ... that kept the slave-trade clause from stating directly 'that there could be property in men.'"

- ↑ Jos. R. Long, "Tinkering with the Constitution", Yale Law Journal, vol. 24, no. 7, May 1915, 579

- 1 2 3 Ewen Cameron Mac Veagh, "The Other Rejected Amendments", The North American Review, vol. 222, no. 829, December 1925, 281-2

- ↑ Russell L. Caplan, Constitutional Brinksmanship: Amending the Constitution by National Convention (Oxford University Press, 1988), 56

- 1 2 Orville James Victor, The History, Civil, Political and Military, of the Southern Rebellion (NY: James D Torrey, 1861), I, 463

- ↑ Francis Newton Thorpe, A Short Constitutional History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, 1904), 207

- ↑ Congressional Globe, p. 1285; Victor, 467

- ↑ Congressional Globe, p. 1403

- ↑ Mark E. Brandon, "The 'Original' Thirteenth Amendment and the Limits to Formal Constitutional Change", in Sanford Levinson, ed., Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment (Princeton University Press, 1995), 219

- 1 2 Brandon, 219-20

- ↑ Alexander Tsesis, The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History (New York University Press, 2004), 2

- ↑ Text of Lincoln's first inaugural address, accessed July 17, 2011

- ↑ Lupton, John A (2006). "Abraham Lincoln and the Corwin Amendment". Illinois Periodicals Online. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Harold Holzer, Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861 (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 429

- ↑ Congressional Globe, pp. 522-523

- ↑ Congressional Globe, p. 2218; Mac Veagh, 282-3; Caplan, 128

- 1 2 3 Crofts, Daniel W. (2016). Lincoln and the Politics of Slavery: The Other Thirteenth Amendment and the Struggle to Save the Union. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 245–250. ISBN 9781469627328.

- ↑ Resolution 10. Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Passed at the Called Session which was Begun and Held in the City of Frankfort, on Thursday, the 17th Day of January 1861 and Ended on Friday, the Fifth Day of April 1861. Frankfort: Commonwealth of Kentucky. 1861. pp. 51–52 – via Google Books.

- ↑ 58 Ohio Laws 190

- ↑ 61 Ohio Laws 182

- ↑ "Adoption of the Corwin Amendment". Providence Evening Press. 3 June 1861. p. 2 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- ↑ Laws of the State of Maryland, Made and Passed At a Session of the General Assembly begun and held at the City of Annapolis on the third day of December, 1861, and ended on the tenth day of March, 1862. (Chapter 21, pages 21 and 22)

- ↑ "Rescission of Maryland's Ratification of the Corwin Amendment to the United States Constitution". General Assembly of Maryland. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ↑ The Illinois legislators decided that the national crisis justified their action, which they recognized as irregular. Philip L. Martin, "Convention Ratification of Federal Constitutional Amendments", Political Science Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 1, March 1967, 65

- ↑ House Joint Resolution No. 67, 58th Texas Legislature, Regular Session, 1963

- ↑ "Slavery: Just a "Detail"?". The Progress Report. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ Linder, Douglas. "What in the Constitution Cannot be Amended?". Arizona Law Review: 717.. See also: Michael Stokes Paulsen, "A General Theory of Article V: The Constitutional Lessons of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment", Yale Law Journal, vol. 103, no. 3, December 1993, 699n79, 702-4, 754n258: "[I]f the meaning of the amendment is judged by its text, rather than by historical evidence of those proposing it, the Corwin Amendment merely prohibits prospectively the enactment of new constitutional amendments giving Congress power to abolish slavery. ... The Corwin Amendment by its terms, is not a slavery-entrenching amendment, but a status-quo-entrenching amendment; and the legal status quo today is that slavery is prohibited." (emphasis in original)

- ↑ Albert, Richard (2013-02-27). "The Unamendable Corwin Amendment". Int'l J. Const. L. Blog. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

Further reading

- Bryant, A. Christopher (2003). "Stopping Time: The Pro-Slavery and 'Irrevocable' Thirteenth Amendment". Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. 26: 501. ISSN 0193-4872.

- Crofts, Daniel W (2016). Lincoln and the Politics of Slavery: The Other Thirteenth Amendment and the Struggle to Save the Union. University of North Carolina Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2731-1.; comprehensive scholarly history of Corwin amendment.

- Lee, R. Alton (1961). "The Corwin Amendment in the Secession Crisis". The Ohio Historical Quarterly. 70 (1): 1–26.

- Martin, Philip E. (1966). "Illinois' Ratification of the Corwin Amendment". Journal of Public Law. 15: 18–91.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Suber, Peter (1990). "The Paradox of Self-Amendment (Section on Corwin Amendment)".

- Bryant, A Christopher (April 1, 2003). "Stopping time: The pro-slavery and "irrevocable" Thirteenth Amendment". Allbusiness.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008.

- Signed letter from Abraham Lincoln transmitting the Corwin Amendment to North Carolina Governor John W. Ellis, March 16, 1861

- "Abraham Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment that Wasn't". This Cruel War Blog. June 16, 2016.

- History of the 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention, which voted to ratify the Corwin Amendment.