Dark City (1998 film)

| Dark City | |

|---|---|

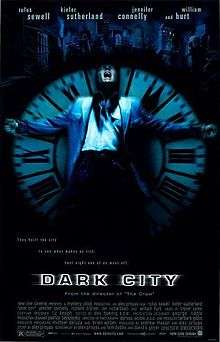

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alex Proyas |

| Produced by |

Andrew Mason Alex Proyas |

| Screenplay by |

Alex Proyas Lem Dobbs David S. Goyer |

| Story by | Alex Proyas |

| Starring |

Rufus Sewell Kiefer Sutherland Jennifer Connelly Richard O'Brien Ian Richardson William Hurt |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Cinematography | Dariusz Wolski |

| Edited by | Dov Hoenig |

Production company |

Mystery Clock Cinema |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

100 minutes (theatrical cut) 111 minutes (director's cut) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $27 million[1] |

| Box office | $27.2 million[2] |

Dark City is a 1998 American neo-noir science fiction film directed by Alex Proyas. The screenplay was written by Proyas, Lem Dobbs and David S. Goyer. The film stars Rufus Sewell, Kiefer Sutherland, Jennifer Connelly, and William Hurt. Sewell plays John Murdoch, an amnesiac man who finds himself suspected of murder. Murdoch attempts to discover his true identity and clear his name while on the run from the police and a mysterious group known only as the "Strangers".[3]

The majority of the film was shot at Fox Studios Australia. It was jointly produced by New Line Cinema and Mystery Clock Cinema. New Line Cinema distributed the theatrical release. The film premiered in the United States on February 27, 1998, and was a box office bomb, but received mainly positive reviews. The film was nominated for Hugo and Saturn Awards, and has become a cult film. For the theatrical release, the studio was concerned that the audience would not understand the film and asked Proyas to add an explanatory voice-over narration to the introduction. A director's cut was released in 2008, restoring and preserving Proyas's original artistic vision for the film. Some critics have noted its similarities and possible influence on the Matrix series, which came out a year later.[4][5][6]

Plot

John Murdoch (Rufus Sewell) awakens in a hotel bathtub, suffering from amnesia. He receives a phone call from Dr. Daniel Schreber (Kiefer Sutherland), who urges him to flee the hotel to evade a group of men who are after him. During the phone talk, Murdoch discovers the corpse of a brutalized, ritualistically murdered woman, along with a bloody knife. He flees the scene, just as the group of men (known as the Strangers) show up to investigate the room.

Eventually Murdoch learns his own name, and finds he has a wife named Emma (Jennifer Connelly). He is also sought by police inspector Frank Bumstead (William Hurt) as a suspect in a series of murders committed around the city, though he cannot remember killing anybody. While being pursued by the Strangers, Murdoch discovers that he has mind powers—which the Strangers also possess, and refer to as "tuning"—and he manages to use these powers to escape from them.

Murdoch explores the city, where nobody realizes that it is always nighttime. At midnight, he watches as everyone except himself falls asleep as the Strangers stop time and physically rearrange the city as well as changing people's identities and memories. Murdoch learns that he comes from a coastal town called Shell Beach, a town familiar to everyone, though nobody knows how to leave the city to travel there, and all of his attempts to do so are unsuccessful for varying reasons. Meanwhile, the Strangers inject one of their men, Mr. Hand (Richard O'Brien), with memories intended for Murdoch in an attempt to predict his movements and track him down.

Murdoch is eventually caught by inspector Bumstead, who acknowledges he is innocent, and by then has his own misgivings about the nature of the city. They confront Dr. Schreber, who explains that the Strangers are endangered extraterrestrial parasites who use corpses as their hosts. Having a hive mind, the Strangers have been experimenting with humans to analyze their individuality in the hopes that some insight might be revealed that would help their race survive.

Schreber reveals that Murdoch is an anomaly who inadvertently awoke during one midnight process, when Schreber was in the middle of imprinting his latest identity as a murderer. The three embark to find Shell Beach, but it exists only as a poster on a wall at the edge of the city. Frustrated, Murdoch and Bumstead break through the wall, revealing outer space on the other side. The men are confronted by the Strangers, including Mr. Hand, who holds Emma hostage. In the ensuing fight Bumstead and one of the Strangers fall through the hole, revealing the city as an enormous space habitat surrounded by a force field.

The Strangers bring Murdoch to their home beneath the city and force Dr. Schreber to imprint Murdoch with their collective memory, believing Murdoch to be the final result of their experiments. Schreber betrays them by inserting false memories in Murdoch which artificially reestablish his childhood as years spent training and honing his psychokinetic skills and learning about the Strangers and their machines. Murdoch awakens, fully realizing his skills, frees himself and battles with the Strangers, defeating their leader Mr. Book (Ian Richardson) in a psychokinetic fight high above the city.

After learning from Dr. Schreber that Emma's personality is gone and cannot be restored, Murdoch exercises his new-found powers, amplified by the Strangers' machine, to create an actual Shell Beach by flooding the area within the force field with water and forming mountains and beaches. On his way to Shell Beach, Murdoch encounters Mr. Hand and informs him that the Strangers have been searching in the wrong place—the mind—to understand humanity. Murdoch turns the habitat toward the star it had been turned away from, and the city experiences sunlight for the first time.

He opens the door leading out of the city, and steps out to view the sunrise. Beyond him is a pier, where he finds the woman he knew as Emma, now with new memories and a new identity as Anna. Murdoch reintroduces himself as they walk to Shell Beach, beginning their relationship anew.

Cast

- Rufus Sewell as John Murdoch

- William Hurt as Inspector Frank Bumstead

- Kiefer Sutherland as Dr. Daniel P. Schreber

- Jennifer Connelly as Emma Murdoch / Anna

- Richard O'Brien as Mr. Hand

- Ian Richardson as Mr. Book

- Bruce Spence as Mr. Wall

- Colin Friels as Det. Eddie Walenski

- John Bluthal as Karl Harris

- Melissa George as May

- Ritchie Singer as Hotel Manager / Vendor

- Nicholas Bell as Mr. Rain

- David Wenham as Schreber's Assistant

- Mitchell Butel as Husselbeck

Cast notes

Alex Proyas based The Strangers on Richard O'Brien's character in The Rocky Horror Show, Riff Raff. Proyas said, "I had Richard in mind physically when I wrote the character, because I had these strange, bald-looking men with an ethereal, androgynous quality." When Proyas visited London to cast for the film, he met with O'Brien and found him suitable for the role.[7]

Kiefer Sutherland's character Daniel P. Schreber is named after Daniel Paul Schreber, a German judge who suffered from narcissistic, paranoid psychosis and possibly schizophrenia and whose autobiographical Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (Denkwürdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken) the film's plot alludes to at various instances.[8][9][10] Hurt was originally asked to play Dr. Schreber.[7]

Setting

The City

The film is set in a city of indeterminate era,[11] placed on an enormous flat-shaped space habitat, which has its own force field and an artificial atmosphere to provide air. It is located close to an unnamed star, but since The Strangers cannot stand light, the city is turned away from it in order to keep it in perpetual nighttime. However, due to this eternal darkness, every citizen has to be put to sleep every night at midnight, and the clocks must be stopped and restarted in order to keep the appearance that no time has passed. All of the residents are completely unaware of the city's true nature and believe that they are still on Earth, although the Earth has not been directly referenced.

A frequently mentioned location in the city is Shell Beach, of which Murdoch has memories growing up. However, Shell Beach is actually non-existent, existing on city maps and frequently mentioned by citizens; yet, nobody knows how to actually go to Shell Beach. In many scenes of the film, Murdoch is seen frequently attempting to arrive at Shell Beach, but always ultimately failing (the train that runs to Shell Beach doesn't stop at any station, no other trains run there, the buses don't drive there, etc.). Eventually, Schreber reveals that Shell Beach is just a poster on an edge of the city. In the end, Murdoch uses his powers to create an actual Shell Beach on the outer side of the habitat, providing access to it.

The Strangers

The Strangers, as noted by Schreber, are endangered extraterrestrial parasites. They use corpses of previous citizens as their hosts, their real form being bio-luminiscent creatures shaped like spiders. If their body dies, the creature will venture out of the corpse from the top of the head and seek another body to host. In their human form, all strangers are pale, bald men, and only one Stranger was seen taking the form of a child.

The Strangers are dying in numbers, and the ones on the habitat are the last of their race. They have a group mind to share, and they have abducted humans a few years before the story started. They have been trying to understand the individuality of a human mind, believing that it holds the key to ensure their survival. However, as noted by Murdoch itself, they have been trying to understand the human mind, which he believes that "it is the wrong place to search" in order to understand humanity, and stating that the human soul is the key to the individuality of a human being.

The Strangers are sensitive to light, which explains perpetual nighttime, and they are sensitive to chlorine and water in general, which is why Schreber spends his free time in a public pool, knowing that they would try to avoid it. However, one Stranger visited him in a public pool without any effect, although his facial expression shows him being revolted at the smell. All the Strangers are dressed in black overcoats and wear hats.

The Strangers have the powers to alter entire structures at will, raising buildings and tearing down others in mere seconds. They are also able to expand or narrow a room and alter its general appearance (replacing furniture, wallpaper, etc.). They are able to freeze every human being they control, during which they alter memories of several citizens to completely different personalities, also altering their living space. They do this every few hours, where they also alter the time back in order to keep the idea of citizens still living in a single day. They must be careful to change the identities of every citizen often, otherwise they will suspect their surroundings and grow paranoid (as shown when Murdoch is confronted by a man who hasn't been altered in a while, and who committed suicide). Schreber is their human contact, a former Earth psychiatrist, who is aware of their existence and their plans but is forced to co-operate and alter minds for them in exchange for his life.

Themes

One of the things that we're exploring in this film, is what it is that makes us who we are. And, when you strip an individual of his identity, is there some spark, some essence there that keeps them being human, gives them some sort of identity?

Alex Proyas[12]

Theologian Gerard Loughlin interprets Dark City as a retelling of Plato's Allegory of the Cave. For Loughlin, the city dwellers are prisoners who do not realize they are in a prison. John Murdoch's escape from the prison parallels the escape from the cave in the allegory. He is assisted by Dr. Schreber, who explains the city's mechanism as Socrates explains to Glaucon how the shadows in the cave are cast. Murdoch however becomes more than Glaucon; Loughlin writes, "He is a Glaucon who comes to realize that Socrates' tale of an upper, more real world, is itself a shadow, a forgery."[13]

Murdoch defeats the Strangers who control the inhabitants and remakes the world based on childhood memories, which were themselves illusions arranged by the Strangers. Loughlin writes of the lack of background, "The origin of the city is off–stage, unknown and unknowable." Murdoch now casts new shadows for the city inhabitants, who must trust his judgment. Unlike Plato, Murdoch "is disabused of any hope of an outside" and becomes the demiurge for the cave, the only environment he knows.[13]

The city in Dark City is described by Higley as a "murky, nightmarish German expressionist film noir depiction of urban repression and mechanism". The city has a World War II dreariness reminiscent of Edward Hopper's works and has details from different eras and architectures that are changed by the Strangers; "buildings collapse as others emerge and battle with one another at the end". The round window in Dark City is concave like a fishbowl and is a frequently seen element throughout the city. The inhabitants do not live at the top of the city; the main characters' homes are dwarfed by the bricolage of buildings.[14]

The film also contains motifs from Greek mythology, in which gods manipulate humans in a higher agenda. Proyas said, "I do like Greek mythology and have read a little of it, so maybe some of it has crept into the work, though I don't completely agree with that point of view."[15]

Production

Influences

Proyas referenced film noir of the 1940s and the 1950s (such as The Maltese Falcon) an influence for the film.[16] It has additionally been described as Kafkaesque, and Proyas cited the TV series The Twilight Zone as a conscious influence.[17] Proyas wanted the film, though nominally science fiction, to have an element of horror to unsettle the audience.[7]

Writing

Proyas co-wrote the screenplay with Lem Dobbs and David S. Goyer. Goyer had written The Crow: City of Angels, the sequel to Proyas's 1994 film The Crow; Proyas invited Goyer to co-write the screenplay for Dark City after reading Goyer's screenplay for Blade, which had yet to be released. Writers Guild of America initially protested at crediting more than two screenwriters for a film, but it eventually relented and credited all three writers.[18] Proyas originally conceived a story about a 1940s detective who is obsessed with facts and cannot solve a case where the facts do not make sense. "He slowly starts to go insane through the story," says Proyas. "He can't put the facts together because they don't add up to anything rational."[19] In the process of creating the fictional world for the character of the detective, Proyas created other characters, shifting the focus of the film from the detective (Bumstead) to the person pursued by the detective (Murdoch). Proyas envisioned a robust narrative where the audience could examine the film from the perspective of multiple characters and focus on the plot.[16]

Design

When Proyas finished his preceding film The Crow in 1994, he approached production designer Patrick Tatopoulos to draw concepts for the world in which Dark City takes place.[20] The city where the story takes place was entirely constructed on a set; no practical locations were used in the film.[19] Tatopoulos described the city:[21]

The movie takes place everywhere, and it takes place nowhere. It's a city built of pieces of cities. A corner from one place, another from some place else. So, you don't really know where you are. A piece will look like a street in London, but a portion of the architecture looks like New York, but the bottom of the architecture looks again like a European city. You're there, but you don't know where you are. It's like every time you travel, you'll be lost.

The production design included themes of darkness, spirals, and clocks. There appears to be no sun in the city's world, and spiral designs that shrink when approached were used in the film. A major clock in the film shows no hours; Tatopoulos said, "But in a magical moment it becomes something more than just a clock."[21] The production designer created the city architecture to have an organic presence with the structural elements.[22]

The Strangers are energy beings who reside in dead human bodies. When design first started, the filmmakers considered having the Strangers be bugs underneath but decided that the bug appearance was overused. Tatopoulos said Proyas wanted to make the Strangers energy beings, "Alex called me and said he wanted something like an energy that kept re-powering itself, re-creating itself, re-shaping itself, sitting inside a dry piece of human shape."[23] The Strangers reside in a large underground amphitheater for their lair, where a human bust hides a large clock and a spiraling device changes the layout of the city above. The set for the lair was fifty feet (15 m) in height, where an average set is thirty-six feet (11 m). The lair set was built on a fairground in Sydney, Australia. The film's budget was $30–40 million,[24] so the crew used inexpensive techniques to design the set, such as stretching canvas onto welded metal frames. The lair also had a rail conveyance that appeared expensive. Tatopoulos said, "We had, obviously, a car built, but we had just one built. We laid some rail for it to ride on. We made a section of corridor that we kept driving through all the time, and you end up believing this thing is running along forever." Proyas originally wanted the rail car to roll by various rooms, which was not feasible for the budget, so Tatopoulos and the crew used "replaceable elements and strong design textures" to mimic the impression of various rooms.[25]

Soundtrack

The film soundtrack was released on February 24, 1998 by TVT Records label.[26] It features music from the original score by Trevor Jones, and versions of the songs "Sway" and "The Night Has a Thousand Eyes" performed by singer Anita Kelsey. It also includes music by Hughes Hall from the trailer,[27] a song by Echo & the Bunnymen that played over the final credits, as well as songs by Gary Numan and Course of Empire that did not appear in the film. The music for the film was edited by Simon Leadley and Jim Harrison.[28]

Similarities to other works

The film's style is often compared to that of the works of Terry Gilliam (especially Brazil).[29][30][31][32][33][34][35] Some stylistic similarities have also been noted to Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro's 1995 film The City of Lost Children,[36][37] another film inspired particularly by Gilliam (Gilliam had presented Jeunet's & Caro's previous film Delicatessen in North America,[38][39] another film by Jeunet & Caro that was a deliberate homage to Gilliam's style).

The Matrix was released one year after Dark City and was also filmed at Fox Studios in Sydney using some of the same sets.[40] Comparisons have been made between scenes from the movies, making note of similarities in both cinematography and atmosphere, as well as the plot.[41]

Fritz Lang's 1927 movie Metropolis was a major influence on the film, showing through the architecture, concepts of the baseness of humans within a metropolis, and general tone.[42] In one of the documentary shorts featured on the director's cut, the influence of the early German films M and Nosferatu are mentioned.

One of the last scenes of the movie, in which buildings "restore" themselves, is strikingly similar to the last panel of the Akira manga. Proyas called the end battle a "homage to Otomo's Akira".[43]

When Christopher Nolan first started thinking about writing the script for Inception, he was influenced by "that era of movies where you had The Matrix, you had Dark City, you had The Thirteenth Floor and, to a certain extent, you had Memento, too. They were based in the principles that the world around you might not be real".[44]

The film bears similarities to the Russian novel The Doomed City by Russian sci-fi writers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. The novel involves an artificial city surrounded by obstacles (wall, dump, desert) with an artificial sun where people from different time periods and countries are put together in one place as an experiment, with their professions changing constantly.

The film also has numerous similarities both in style and plot development to the short story "The Tunnel under the World".

Release

Dark City was titled Dark World and Dark Empire leading up to the film's release. Warner Bros. wanted the filmmakers to consider the alternate titles due to the release of similarly titled Mad City in the same time frame, but Dark City was ultimately kept as the final title.[16] The film was originally scheduled to be released in theaters on October 17, 1997,[18] and it was later scheduled for January 9, 1998.[16] The film would premiere in theaters nationwide in the United States on February 27, 1998, screening at 1,754 cinemas.[2]

Reception

Critical response

Among mainstream critics in the U.S., the film received generally positive reviews.[45] Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 74% of 81 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 6.9 out of 10 and the critical consensus stating: "Stylishly gloomy, Dark City offers a polarizing whirl of arresting visuals and noirish action".[46] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average out of 100 to critics' reviews, the film received a score of 66 based on 23 reviews.[45]

| "No movie can ever have too much atmosphere, and Dark City exudes it from every frame of celluloid. Proyas' world isn't just a playground for his characters to romp in — it's an ominous place where viewers can get lost. We don't just coolly observe the bizarre, ever-changing skyline; we plunge into the city's benighted depths, following the protagonist as he explores the secrets of this grim place where the sun never shines. Dark City has as stunning a visual texture as that of any movie that I've seen." |

| —James Berardinelli, writing for ReelViews[47] |

Roger Ebert writing in the Chicago Sun-Times called it a "great visionary achievement," while also exclaiming that it was "a film so original and exciting, it stirred my imagination like Metropolis and 2001: A Space Odyssey."[48] In the San Francisco Chronicle, Peter Stack wrote that the film was "among the most memorable cinematic ventures in recent years", and that "maybe there's nothing wrong with a movie that is simply sensational to look at." He felt the film's "twisting of reality and its daring look — layered and off-kilter grays, greens and blacks — make it click."[49] In a mixed review, Walter Addiego of The San Francisco Examiner thought "as a story, Dark City doesn't amount to much." He believed Dark City contained a "complicated plot" while also having important themes that were "no more than window dressing". But on a positive front, he wrote, "what counts here is the show, the creation of a strange world by a filmmaker who clearly knows science fiction and fantasy, past and present, and wants to share his love for it."[50]

Left unimpressed, Marc Savlov of The Austin Chronicle wrote, "You really have to feel for Alex Proyas. This guy wears bad luck like the grimy trenchcoats of his protagonists, only his zipper's stuck and he can't seem to shake the damn thing off." In expressing his negativity, he believed "Dark City looks like a million bucks (or rather, a million bucks gone to compost), but at its dark heart it's a tedious, bewildering affair, lovely to look at but with all the substance of a dissipating dream."[51] Left equally disappointed was John Anderson of the Los Angeles Times. Commenting on the directing, he thought "If you had to guess, you might say that Proyas came out of the world of comic art himself, rather than music videos and advertising. Dark City is constructed like panels in a Batman book, each picture striving for maximum dread." He went on to say, Proyas was "trying simultaneously to create a pure thriller and sci-fi nightmare along with his tongue-in-cheek critique of artifice. And this doesn't work out quite so well."[52] Author TCh of Time Out, felt the development of the Murdoch character was "surprisingly engrossing" and thought production wise, the "art direction is always striking, and unlike most contemporary sci-fi, the movie does risk a cerebral approach, tapping a vein of postmodern paranoia."[53]

Writing for TIME, Richard Corliss said the film was "as cool and distant as the planet the Strangers come from. But, Lord, is Dark City a wonder to see."[54] James Berardinelli writing for ReelViews, remarked that "Visually, this film isn't just impressive, it's a tour de force." and noted that "Dark City opens by immersing the audience in the midst of a fractured, nightmarish narrative."[47] Berardinelli also said "Dark City appears to be New York during the first half of this century, but, using a style that is part science fiction, part noir thriller, and part gothic horror, he has embellished it to create a surreal place unlike no other."[47] Describing some pitfalls, Jeff Vice of the Deseret News said that "when critics talk about films being 'style over substance,' they're definitely talking about movies like Dark City, which looks good but leaves an unpleasant aftertaste."[55] Vice however was quick to admit, "The special effects and set designs are dazzling", but ultimately believed "Proyas makes a crucial error in treating the subject even more seriously than The Crow, and the dialogue (co-written by Proyas and The Crow: City of Angels scriptwriter David S. Goyer) is unintentionally funny at times and often just plain dumb."[55]

"What they have done is taken a few second-hand ideas from noir and speculative fiction and mixed them in occasionally striking ways, even if, in the end, the result isn't all that much fun."—Todd McCarthy, writing in Variety[56]

Andrea Basora of Newsweek, stated that director Proyas flooded the screen with "cinematic and literary references ranging from Murnau and Lang to Kafka and Orwell, creating a unique yet utterly convincing world".[57] Similarly, David Sterritt wrote in the Christian Science Monitor that "The story is dark and often violent, but it's told with a remarkable sense of visual energy and imagination."[58] Additionally, Marshall Fine of USA Today, found the film to be "Fascinating, visionary filmmaking." and "With its amber-tinged palette and its distinctively dystopian view of life, it may be the most unique-looking film we've seen in ages...[but] defies logic and makes frightening and unexpected leaps."[59] Critic Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote that the "plot that Dark City builds on John's predicament is a confused affair" and that the film's premise is "unsettling enough to make you wonder if it could actually derail a seriously drug-addled mind."[60]

Steve Biodrowski of Cinefantastique found the production design and the cinematography overwhelming, but he considered the narrative engagement of Sewell's amnesiac character to be ultimately successful. Biodrowski writes, "As the story progresses, the pieces of the puzzle fall into place, and we gradually realize that the film is not a murky muddle of visuals propping up a weak story. All the questions lead to answers, and the answers make sense within the fantasy framework." The reviewer compared Dark City to the director's preceding film The Crow in style but found Dark City to introduce new themes and to be a "more thoroughly consistent" film.[61] Biodrowski concluded, "Dark City may not provide profound answers, but it deals seriously with a profound idea, and does it in a way that is cathartic and even uplifting, without being contrived or condescending. As a technical achievement, it is superb, and that technique is put in the service of telling a story that would be difficult to realize any other way."[62]

Accolades

The film won and was nominated for several awards in 1998. Film critic Roger Ebert cited it as the best film of 1998.[63][64] In 2005, he included it on his "Great Movies" list.[40] Ebert used it in his teaching, and also appears on a commentary track for the original DVD and the 2006 Director's Cut.[40] The film was screened out of competition at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival.[65]

| Award | Category | Name | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amsterdam Fantastic Film Festival | Silver Scream Award | Alex Proyas | Won |

| Bram Stoker Award | Best Screenplay | Alex Proyas, Lem Dobbs, and David S. Goyer | Won (tied with Gods and Monsters) |

| Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film | Pegasus Audience Award | Alex Proyas | Won |

| Film Critics Circle of Australia | Best Screenplay – Original | Alex Proyas, Lem Dobbs, and David S. Goyer | Won (tied with The Interview) |

| Hugo Award | Best Dramatic Presentation | Nominated | |

| International Horror Guild Award | Best Movie | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review | Special Recognition | Won | |

| Saturn Award | Best Science Fiction Film | Won (tied with Armageddon) | |

| Best Costume | Liz Keogh | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Alex Proyas | Nominated | |

| Best Make-Up | Bob McCarron, Lesley Vanderwalt, and Lynn Wheeler | Nominated | |

| Best Special Effects | Andrew Mason, Mara Bryan, Peter Doyle, and Tom Davies | Nominated | |

| Best Writer | Alex Proyas, Lem Dobbs, and David S. Goyer | Nominated |

Box office

Dark City premiered in cinemas on February 27, 1998 in wide release on 1,754 screens in the U.S., and grossed $5,576,953 on its opening weekend, placing 4th,[2] far behind Titanic in 1st place with $19,633,056.[66] The film's revenue dropped by 49.1% in its second week of release, earning $2,837,941, dropping to 9th, while Titanic remained in first place with $17,605,849.[67] The film went on to earn $14,378,331 domestically in total ticket sales through a 4-week theatrical run. Internationally, the film took in an additional $12,821,985 in box office business for a combined worldwide total of $27,200,316.[2] The film's cumulative gross ranked 105th for 1998.[68]

Home media

The film was released in VHS video format on March 2, 1999.[69] The Region 1 Code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on July 29, 1998. Special features for the DVD include two audio commentary tracks, one with film critic Roger Ebert, and one with director Alex Proyas, writers Lem Dobbs and David Goyer, and production designer Patrick Tatopoulos. The DVD also includes biographies, filmographies, comparisons to Fritz Lang's Metropolis, set designs, and the theatrical trailer.[70]

A director's cut of Dark City was also officially released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc on July 29, 2008. The director's cut removes the opening narration, which Proyas felt explained too much of the plot, and restores it to its original location in the film. It also includes 15 minutes of additional footage, mostly consisting of extended scenes with additional establishing shots and dialogue.[71] Expanded audio commentaries by Ebert, Proyas, Dobbs and Goyer are included, along with several new documentaries. The Blu-ray disc additionally includes the original theatrical cut and the special features from the 1998 DVD release.

See also

References

- ↑ "Movie Dark City - Box Office Data". The Numbers. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Dark City (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Helms, Michael (May 1998). "Dark City: Interview with Andrew Mason and Alex Proyas". Cinema Papers. North Melbourne: Cinema Papers Pty Ltd. (124): 18–21. ISSN 0311-3639.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (31 March 1999). "The Matrix". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ "Dark City vs The Matrix". RetroJunk. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Tyridal, Simon (28 January 2005). "Matrix City: A Photographic Comparison of The Matrix and Dark City". ElectroLund. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Wagner 1997a, p. 9

- ↑ Kemble, Gary (2009). Movie Minutiae: Dark City (1998). ABCNews. Articulate: Daily talk on arts news and events. 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Harris, Ken: Film and Conspiracy, in: Knight, Peter (2003). Conspiracy theories in American history: an encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO Inc., Santa Barbara, California, ISBN 1-57607-812-4, p. 262

- ↑ Bould, Mark. On the Boundary between Oneself and the Other: Aliens and Language in the Films AVP, Dark City, The Brother from Another Planet, and Possible Worlds, Yearbook of English Studies, University of West of England

- ↑ Proyas, Alex (Director) (2008). Dark City, Director's Cut: at approximately 1:08, Mr. Hand states that the city is a mix of eras. (BlueRay disc)

- ↑ Proyas, Alex (Director) (2008). Dark City (Director's Cut Commentary) (DVD). Event occurs at 1:15:23-1:17:40.

And so for me, the love story aspect of this film, the love affair between Murdoch and his wife, that kind of grows and sort of comes to a culmination in this scene, [Scene 12, "Do You Remember?"] is for me exploring that idea, and how, when you take away both of these people, these character's identity, is there something left, something that they acknowledge or recognize within each other, that is expressed as love for each other? For me the question is, if there was a man and a woman who were in love who were married let's say, and who had been together for a very long time, if by some strange procedure they could have their memories erased, and then they would re-meet, would they fall in love again? Is love some kind of a force that rules us beyond our identification with each other and ourselves? My feeling is that's probably the case. I don't think any scientist has fully resolved why two people amongst the many millions of people in the world and the many thousands they might meet, why you find a partner and have this bond with a particular person. So my belief is that it is a very fundamental aspect of the way we function as human beings and that perhaps it's something that rules us, that drugs us in ways we can't explain or understand.

- 1 2 Loughlin, Gerard (February 2004), "Seeing in the Dark", Alien Sex: The Body and Desire in Cinema and Theology, Wiley–Blackwell, pp. 46–48, ISBN 0-631-21180-2

- ↑ Higley, Sarah L. (2001), "A Taste for Shrinking: Movie Miniatures and the Unreal City", Camera Obscura, Duke University Press, 16 (2 47): 9–12, ISSN 0270-5346

- ↑ Wagner 1998a, pp. 40–41

- 1 2 3 4 Wagner 1998a, p. 40

- ↑ Wagner 1997a, p. 8

- 1 2 Wagner 1997b, p. 67

- 1 2 Wagner 1997a, p. 7

- ↑ Wagner 1997b, p. 64

- 1 2 Wagner 1997b, p. 65

- ↑ Wagner 1997b, p. 66

- ↑ Wagner 1998b, p. 32

- ↑ Wagner 1998b, p. 33

- ↑ Wagner 1998b, p. 34

- ↑ Fawthrop, Peter. "Dark City (Original Soundtrack)". Allmusic. Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- ↑ Dark City trailer (QuickTime). Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ "Dark City (1998)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ↑ Hicks, Adrienne. "DARK CITY" (1998): Critical Review and Bibliography

- ↑ Blackwelder, Rob. Visions of 'strangers' dance in his head: 30 minutes with 'Dark City' writer-director Alex Proyas, SPLICEDwire

- ↑ Dunne, Susan (2006).Welcome To Dystopia At Trinity's Cinestudio, Hartford Courant, February 23rd, 2006

- ↑ Fisher, Russ (2008). Why Dark City is What The Fuck?, chud.com

- ↑ ‘Dark City’', Hayden Reviews, March 9th, 2009

- ↑ Maciak, Luke (2010). Dark City, Terminally Incoherent, October 15th, 2010

- ↑ Wroblewski, Greg. Dark City (1998), Scoopy.com

- ↑ Carpenter, Jerry, "The City of Lost Children", Movie Reviews, SciFilm.org, archived from the original (review) on 2007-10-12, retrieved 2007-11-07,

The production design by Jean Rabasse is marvelous. The city is dark and damp, all stairs and walkways. It clearly served as inspiration for DARK CITY three years later—- one scene even features sharply inclined risers filled with members of the cyclops cult just like those used by the cenobites in the later film.

- ↑ Mestas, Alex (2003-03-03), "The City of Lost Children (1995)", DVD Reviews, LightsOutFilms.com, archived from the original (review) on September 7, 2008, retrieved 2007-11-07,

The film is similar in theme and execution to the slightly better Dark City.

- ↑ < SFrevu.com

- ↑ Clark, Mike (2006-05-05). "New on DVD". USA Today.

- 1 2 3 Ebert, Roger. Great Movies: Dark City (2005). 2005-11-06.

- ↑ Morales, Jorge. Comparación de los Filmes "Dark City" & "The Matrix". Retrieved 2005-12-24. (Spanish)

- ↑ "The Metropolis Comparison". Dark City DVD (1998).

- ↑ Proyas, Alex. Dark City DC: Original Ending !? at the Wayback Machine (archived October 14, 2007). Mystery Clock Forum. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ↑ Boucher, Geoff (2010-04-04). "Inception breaks into dreams". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- 1 2 Dark City. Metacritic. CNET Networks. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Dark City (1998). Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- 1 2 3 Berardinelli, James (1998). Dark City. ReelViews. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (27 February 1998). Dark City. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Stack, Peter (27 February 1998). Stunning visuals overshadow thriller's muddled plot. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Addiego, Walter (27 February 1998). Grave new world with a murky plot. The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Savlov, Marc (27 February 1998). Dark City. Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Anderson, John (27 February 1998). Dark City. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ TCh (1997). Dark City. Time Out. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (2 March 1998). Dark City. TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- 1 2 Vice, Jeff (27 February 1998). Dark City. Deseret News. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd (19 February 1998). Dark City. Variety Magazine. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Basora, Andrea (1998). Dark City. Newsweek. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Sterritt, David (1998). Dark City. Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Fine, Marshall (1998). Dark City. USA Today. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (27 February 1998). Dark City: You Are Getting Sleepy: Who Are You, Anyway?. The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Biodrowski 1998, p. 35

- ↑ Biodrowski 1998, p. 61

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (February 27, 1998), "Dark City", Chicago Sun-Times, retrieved 2009-07-28

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "The Best 10 Movies of 1998". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2005-12-20.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Dark City", festival-cannes.com, retrieved 2009-10-04

- ↑ "February 27-March 1, 1998 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ "March 6–8, 1998 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ "Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ "Dark City VHS Format". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ "Dark City DVD". DVDEmpire.com. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ↑ Alex Proyas Interview - Dark City Director's Cut and More. twitchfilm.net. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- Biodrowski, Steve (April 1998), "Dark City – Review", Cinefantastique, 29 (12): 35, 61, ISSN 0145-6032

- Khoury, George (September 2000), "The Imagineer: An Interview with Alex Proyas", Creative Screenwriting, 7 (5): 83–90, ISSN 1084-8665

- Wagner, Chuck (September 1997a), "Dark World", Cinefantastique, 29 (3): 7–9, ISSN 0145-6032

- Wagner, Chuck (October 1997b), "Dark Empire", Cinefantastique, 29 (4/5): 64–67, ISSN 0145-6032

- Wagner, Chuck (January 1998a), "Dark City", Cinefantastique, 29 (9): 40–41, ISSN 0145-6032

- Wagner, Chuck (April 1998b), "Dark City", Cinefantastique, 29 (12): 32–34, ISSN 0145-6032

- Wilson, Eric G. (2006), "Gnostic Paranola in Proyas's Dark City", Film/Literature Quarterly, 34 (3): 232–239

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dark City |

- Dark City at the Internet Movie Database

- Dark City at AllMovie

- Dark City at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dark City at Metacritic

- Dark City at Box Office Mojo