Dawes Act

.svg.png) | |

| Other short titles | Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 |

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes. |

| Nicknames | General Allotment Act of 1887 |

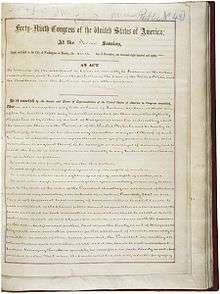

| Enacted by | the 49th United States Congress |

| Effective | February 8, 1887 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 49-119 |

| Statutes at Large | 24 Stat. 387 aka 24 Stat. 388 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 25 U.S.C.: Indians |

| U.S.C. sections created | 25 U.S.C. ch. 9 § 331 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887),[1][2] adopted by Congress in 1887, authorized the President of the United States to survey American Indian tribal land and divide it into allotments for individual Indians. Those who accepted allotments and lived separately from the tribe would be granted United States citizenship. The Dawes Act was amended in 1891, in 1898 by the Curtis Act, and again in 1906 by the Burke Act.

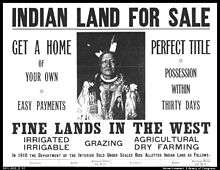

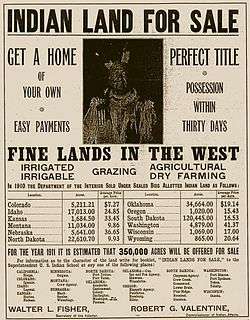

The Act was named for its creator, Senator Henry Laurens Dawes of Massachusetts. The objectives of the Dawes Act were to lift the Native Americans out of poverty and to stimulate assimilation of them into mainstream American society. Individual household ownership of land and subsistence farming on the European-American model was seen as an essential step. The act also provided what the government would classify as "excess" those Indian reservation lands remaining after allotments, and sell those lands on the open market, allowing purchase and settlement by non-Native Americans.

The Dawes Commission, set up under an Indian Office appropriation bill in 1893, was created to try to persuade the Five Civilized Tribes to agree to allotment plans. (They had been excluded from the Dawes Act by their treaties.) This commission registered the members of the Five Civilized Tribes on what became known as the Dawes Rolls.

The Curtis Act of 1898 amended the Dawes Act to extend its provisions to the Five Civilized Tribes; it required abolition of their governments, allotment of communal lands to people registered as tribal members, and sale of lands declared surplus, as well as dissolving tribal courts. This completed the extinguishment of tribal land titles in Indian Territory, preparing it to be admitted to the Union as the state of Oklahoma.

During the ensuing decades, the Five Civilized Tribes lost 90 million acres of former communal lands, which were sold to non-Natives. In addition, many individuals, unfamiliar with land ownership, the target of speculators and criminals, and stuck with allotments that were too small for profitable farming, lost their household lands. Tribe members also suffered from the breakdown of the social structure of the tribes.

During the Great Depression, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration supported passage on June 18, 1934 of the US Indian Reorganization Act (also known as the Wheeler-Howard Law). It ended land allotment and created a "New Deal" for Indians, renewing their rights to reorganize and form their self-governments.[3]

The Indian Problem

During the 1850s, the United States federal government's attempt to exert control over the Native Americans expanded. Numerous new European immigrants were settling on the eastern border of the Indian territories, where most of the Native Americans tribes were situated. Conflicts between the groups increased as they competed for resources and operated according to different cultural systems. Many European Americans did not believe that members of the two racial societies could coexist within the same communities. Searching for a quick solution to their problem, William Medill the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, proposed establishing "colonies" or "reservations" that would be exclusively for the natives, similar to those which some native tribes had created for themselves in the east.[4] It was a form of removal whereby the US government would uproot the natives from their current locations to positions to areas in the region beyond the Mississippi River; this would enable settlement by European Americans in the Southeast in turn opening up new placement for the new white settlers and at the same time protecting them from the corrupt "evil" ways of the subordinate natives.[5]

The new policy intended to concentrate Native Americans in areas away from encroaching settlers, but it caused considerable suffering and many deaths. During the nineteenth century, Native American tribes resisted the imposition of the reservation system and engaged with the United States Army in what were called the Indian Wars in the West for decades. Finally defeated by the US military force and continuing waves of encroaching settlers, the tribes negotiated agreements to resettle on reservations.[6] Native Americans ended up with a total of over 155 million acres (630,000 km2) of land, ranging from arid deserts to prime agricultural land.[7]

The Reservation system, though forced upon Native Americans, was a system that allotted each tribe a claim to their new lands, protection over their territories, and the right to govern themselves. With the Senate supposedly being able to intervene only through the negotiation of treaties, they adjusted their ways of life and tried to continue their traditions.[8] The traditional tribal organization, a defining characteristic of Native Americans as a social unit, became apparent to the non-native communities of the United States and created a mixed stir of emotions. The tribe was viewed as a highly cohesive group, led by a hereditary, chosen chief, who exercised power and influence among the members of the tribe by aging traditions.[9] The tribes were seen as strong, tight-knit societies led by powerful men who were opposed to any change that weakened their positions. Many white Americans feared them and sought reformation. The Indians' failure to adopt the "Euroamerican" lifestyle, which was the social norm in the United States at the time, was seen as both unacceptable and uncivilized.

By the end of the 1880s, a general consensus seem to have been reached among many US stakeholders that the assimilation of Native Americans into white American culture was top priority; it was the time for them to leave behind their tribal landholding, reservations, traditions and ultimately their Indian identities.[10]

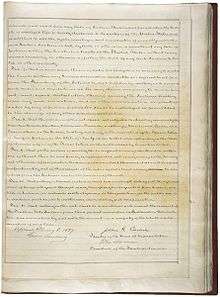

On February 8, 1887, the Dawes Allotment Act was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland.

Responsible for enacting the division of the American native reserves into plots of land for individual households, the Dawes Act was created by reformers to achieve six goals:

- breaking up of tribes as a social unit,

- encouraging individual initiatives,

- furthering the progress of native farmers,

- reducing the cost of native administration,

- securing parts of the reservations as Indian land, and

- opening the remainder of the land to white settlers for profit.[11]

The compulsory Act forced natives to succumb to their inevitable fate; they would undergo severe attempts to become "Euro-Americanized" as the government allotted their reservations with or without their consent. Native Americans held very specific ideologies pertaining to their land, to them the land and earth were things to be valued and cared for, for they represented all things that produced and sustained life, it embodied their existence and identity, and created an environment of belonging.[12] In opposition to their white counterparts, they did not see it from an economic standpoint.

But, many natives began to believe they had to adapt to the majority culture in order to survive. They would have to embrace these beliefs and surrender to the forces of progress. They were to adopt the values of the dominant society and see land as real estate to be bought and developed; they were to learn how to use their land effectively in order to become prosperous farmers.[13] As they were inducted as citizens of the country, they would shed their uncivilized discourses and ideologies, and exchange them for ones that allowed them to become industrious self-supporting citizens, and finally rid themselves of their "need" for government supervision.[14]

Provisions of the Dawes Act

The important provisions of the Dawes Act[2] were:

- A head of family would receive a grant of 160 acres (0.65 km2), a single person or orphan over 18 years of age would receive a grant of 80 acres (320,000 m2), and persons under the age of 18 would receive 40 acres (160,000 m2) each;

- the allotments would be held in trust by the U.S. Government for 25 years;

- Eligible Indians had four years to select their land; afterward the selection would be made for them by the Secretary of the Interior.[15]

Every member of the bands or tribes receiving a land allotment is subject to laws of the state or territory in which they reside. Every Indian who receives a land allotment "and has adopted the habits of civilized life" (lived separate and apart from the tribe) is bestowed with United States citizenship "without in any manner impairing or otherwise affecting the right of any such Indian to tribal or other property."[16]

The Secretary of Interior could issue rules to assure equal distribution of water for irrigation among the tribes, and provided that "no other appropriation or grant of water by any riparian proprietor shall be authorized or permitted to the damage of any other riparian proprietor."[17]

The Dawes Act did not apply to the territory of the:[18]

- Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Miami and Peoria in Indian Territory

- Osage, Sac and Fox, in the Oklahoma Territory

- any of the reservations of the Seneca Nation of New York, or

- a strip of territory in the State of Nebraska adjoining the Sioux Nation

Provisions were later extended to the Wea, Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankeshaw, and Western Miami tribes by act of 1889.[19] Allotment of the lands of these tribes was mandated by the Act of 1891, which amplified the provisions of the Dawes Act.[20]

Dawes Act 1891 Amendments

In 1891 the Dawes Act was amended:[21]

- Allowed for pro-rata distribution when the reservation did not have enough land for each individual to receive allotments in original quantities, and provided that when land is only suitable for grazing purposes, such land be allotted in double quantities[22]

- Established criteria for inheritance[23]

- Does not apply to Cherokee Outlet[24]

Provisions of the Curtis Act

The Curtis Act of 1898 extended the provisions of the Dawes Act to the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory. It did away with their self-government, including tribal courts. In addition to providing for allotment of lands to tribal members, it authorized the Dawes Commission to make determination of members when registering tribal members.

Provisions of the Burke Act

The Burke Act of 1906[25] amended the sections of the Dawes Act dealing with US Citizenship (Section 6) and the mechanism for issuing allotments. The Secretary of Interior could force the Indian Allottee to accept title for land. US Citizenship was granted unconditionally upon receipt of land allotment (the individual did not need to move off the reservation to receive citizenship). Land allotted to Indians was taken out of Trust and subject to taxation. The Burke Act did not apply to any Indians in Indian Territory.

Effects

The Dawes Act had a negative effect on American Indians, as it ended their communal holding of property (with crop land often being privately owned by families or clans[26]), by which they had ensured that everyone had a home and a place in the tribe. The act "was the culmination of American attempts to destroy tribes and their governments and to open Indian lands to settlement by non-Indians and to development by railroads."[27] Land owned by Indians decreased from 138 million acres (560,000 km2) in 1887 to 48 million acres (190,000 km2) in 1934.[28]

Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado was one of the most outspoken opponents of allotment. In 1881, he said that allotment was a policy "to despoil the Indians of their lands and to make them vagabonds on the face of the earth." Teller also said,

"the real aim [of allotment] was "to get at the Indian lands and open them up to settlement. The provisions for the apparent benefit of the Indians are but the pretext to get at his lands and occupy them. ... If this were done in the name of Greed, it would be bad enough; but to do it in the name of Humanity ... is infinitely worse."[29]

The amount of land in native hands rapidly depleted from some 150 million acres (610,000 km2) to a small 78 million acres (320,000 km2) by 1900. The remainder of the land once allotted to appointed natives was declared surplus and sold to non-native settlers as well as railroad and other large corporations; other sections were converted into federal parks and military compounds.[30] The concern shifted from encouraging private native landownership to satisfying the white settlers' demand for larger portions of land.

By dividing reservation lands into privately owned parcels, legislators hoped to complete the assimilation process by forcing Indians to adopt individual households, and strengthen the nuclear family and values of economic dependency strictly within this small household unit.[31]

Given the conditions on the Great Plains, the land granted to most allottees was not sufficient for economic viability of farming. Division of land among heirs upon the allottees' deaths quickly led to land fractionalization. Most allotment land, which could be sold after a statutory period of 25 years, was eventually sold to non-Native buyers at bargain prices. Additionally, land deemed to be "surplus" beyond what was needed for allotment was opened to white settlers, though the profits from the sales of these lands were often invested in programs meant to aid the American Indians. Over the 47 years of the Act's life, Native Americans lost about 90 million acres (360,000 km²) of treaty land, or about two-thirds of the 1887 land base. About 90,000 Native Americans were made landless.[32]

In 1906 the Burke Act (also known as the forced patenting act) amended the GAA to give the Secretary of the Interior the power to issue allottees a patent in fee simple to people classified "competent and capable." The criteria for this determination is unclear but meant that allottees deemed "competent" by the Secretary of the Interior would have their land taken out of trust status, subject to taxation, and could be sold by the allottee. The allotted lands of Indians determined to be incompetent by the Secretary of the Interior were automatically leased out by the Federal Government.[33] The act reads:

... the Secretary of the Interior may, in his discretion, and he is hereby authorized, whenever he shall be satisfied that any Indian allottee is competent and capable of managing his or her affairs at any time to cause to be issued to such allottee a patent in fee simple, and thereafter all restrictions as to sale, encumbrance, or taxation of said land shall be removed.

The use of competence opens up the categorization, making it much more subjective and thus increasing the exclusionary power of the Secretary of Interior. Although this act gives power to the allottee to decide whether to keep or sell the land, given the harsh economic reality of the time, and lack of access to credit and markets, liquidation of Indian lands was almost inevitable. It was known by the Department of Interior that virtually 95% of fee patented land would eventually be sold to whites.[34]

The allotment policy depleted the land base, ending hunting as a means of subsistence. According to Victorian ideals, the men were forced into the fields (but the Indians thought this made them take on what in their society had traditionally been the woman's role, and the women were relegated to the domestic sphere). This Act imposed a patriarchal nuclear household onto many matrilineal Native societies, in which women had controlled property and descent.

Native gender roles and relations quickly changed with this policy, since communal living had shaped the social order of Native communities. Women were no longer the caretakers of the land and they were no longer valued in the public political sphere. Even in the home, the Native woman was dependent on her husband. Before allotment, women divorced easily and had important political and social status, as they were usually the center of their kin network. Under the Dawes Act, to receive the full 160 acres (0.65 km2), women had to be officially married.

In 1926, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work commissioned a study of federal administration of Indian policy and the condition of Indian people. Completed in 1936, The Problem of Indian Administration – commonly known as the Meriam Report after the study's director, Lewis Meriam – documented fraud and misappropriation by government agents. In particular, the Meriam Report found that the General Allotment Act had been used to illegally deprive Native Americans of their land rights.

After considerable debate, Congress terminated the allotment process under the Dawes Act by enacting the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 ("Wheeler-Howard Act"). However, the allotment process in Alaska, under the separate Alaska Native Allotment Act, continued until its revocation in 1993 by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Despite termination of the allotment process in 1934, effects of the General Allotment Act continue into the present. For example, one provision of the Act was the establishment of a trust fund, administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to collect and distribute revenues from oil, mineral, timber, and grazing leases on Native American lands. The BIA's alleged improper management of the trust fund resulted in litigation, in particular the case Cobell v. Kempthorne (settled in 2009 for $3.4 billion), to force a proper accounting of revenues.

Fractionation

For nearly one hundred years, the consequences of federal Indian allotments have developed into the problem of fractionation. As original allottees die, their heirs receive equal, undivided interests in the allottees' lands. In successive generations, smaller undivided interests descend to the next generation. Fractionated interests in individual Indian allotted land continue to expand exponentially with each new generation.

Today, there are approximately four million owner interests in the 10,000,000 acres (40,000 km2) of individually owned trust lands, a situation the magnitude of which makes management of trust assets extremely difficult and costly. These four million interests could expand to 11 million interests by the year 2030 unless an aggressive approach to fractionation is taken. There are now single pieces of property with ownership interests that are less than 0.0000001% or 1/9 millionth of the whole interest, which has an estimated value of .004 cent.

The economic consequences of fractionation are severe. Some recent appraisal studies suggest that when the number of owners of a tract of land reaches between ten and twenty, the value of that tract drops to zero. Highly fractionated land is for all practical purposes worthless.

In addition, the fractionation of land and the resultant ballooning number of trust accounts quickly produced an administrative nightmare. Over the past 40 years, the area of trust land has grown by approximately 80,000 acres (320 km2) per year. Approximately 357 million dollars is collected annually from all sources of trust asset management, including coal sales, timber harvesting, oil and gas leases and other rights-of-way and lease activity. No single fiduciary institution has ever managed as many trust accounts as the Department of the Interior has managed over the last century.

Interior is involved in the management of 100,000 leases for individual Indians and tribes on trust land that encompasses approximately 56,000,000 acres (230,000 km2). Leasing, use permits, sale revenues, and interest of approximately $226 million per year are collected for approximately 230,000 individual Indian money (IIM) accounts, and about $530 million per year are collected for approximately 1,400 tribal accounts. In addition, the trust currently manages approximately $2.8 billion in tribal funds and $400 million in individual Indian funds.

Under current regulations, probates need to be conducted for every account with trust assets, even those with balances between one cent and one dollar. While the average cost for a probate process exceeds $3,000, even a streamlined, expedited process costing as little as $500 would require almost $10,000,000 to probate the $5,700 in these accounts.

Unlike most private trusts, the Federal Government bears the entire cost of administering the Indian trust. As a result, the usual incentives found in the commercial sector for reducing the number of small or inactive accounts do not apply to the Indian trust. Similarly, the United States has not adopted many of the tools that States and local government entities have for ensuring that unclaimed or abandoned property is returned to productive use within the local community.

Fractionation is not a new issue. In the 1920s the Brookings Institution conducted a major study of conditions of the American Indian and included data on the impacts of fractionation. This report, which became known as the Meriam Report, was issued in 1928. Its conclusions and recommendations formed the basis for land reform provisions that were included in what would become the IRA. The original versions of the IRA included two key titles, one dealing with probate and the other with land consolidation. Because of opposition to many of these provisions in Indian Country, often by the major European-American ranchers and industry who leased land and other private interests, most were removed while Congress was considering the bill. The final version of the IRA included only a few basic land reform and probate measures. Although Congress enabled major reforms in the structure of tribes through the IRA and stopped the allotment process, it did not meaningfully address fractionation as had been envisioned by John Collier, then Commissioner of Indian Affairs, or the Brookings Institution.

In 1922, the General Accounting Office (GAO) conducted an audit of 12 reservations to determine the severity of fractionation on those reservations. The GAO found that on the 12 reservations for which it compiled data, there were approximately 80,000 discrete owners but, because of fractionation, there were over a million ownership records associated with those owners. The GAO also found that if the land were physically divided by the fractional interests, many of these interests would represent less than one square foot of ground. In early 2002, the Department of the Interior attempted to replicate the audit methodology used by GAO and to update the GAO report data to assess the continued growth of fractionation; it found that it increased by more than 40% between 1992 and 2002.

As an example of continuing fractionation, consider a real tract identified in 1987 in Hodel v. Irving, 481 U.S. 704 (1987):

Tract 1305 is 40 acres (160,000 m2) and produces $1,080 in income annually. It is valued at $8,000. It has 439 owners, one-third of whom receive less than $.05 in annual rent and two-thirds of whom receive less than $1. The largest interest holder receives $82.85 annually. The common denominator used to compute fractional interests in the property is 3,394,923,840,000. The smallest heir receives $.01 every 177 years. If the tract were sold (assuming the 439 owners could agree) for its estimated $8,000 value, he would be entitled to $.000418. The administrative costs of handling this tract are estimated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs at $17,560 annually. Today, this tract produces $2,000 in income annually and is valued at $22,000. It now has 505 owners but the common denominator used to compute fractional interests has grown to 220,670,049,600,000. If the tract were sold (assuming the 505 owners could agree) for its estimated $22,000 value, the smallest heir would now be entitled to $.00001824. The administrative costs of handling this tract in 2003 are estimated by the BIA at $42,800.

Fractionation has become significantly worse. As noted above, in some cases the land is so highly fractionated that it can never be made productive. With such small ownership interests, it is nearly impossible to obtain the level of consent necessary to lease the land. In addition, to manage highly fractionated parcels of land, the government spends more money probating estates, maintaining title records, leasing the land, and attempting to manage and distribute tiny amounts of income to individual owners than is received in income from the land. In many cases, the costs associated with managing these lands can be significantly more than the value of the underlying asset.

Contemporary interpretations

Angie Debo's landmark work, And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (1940), claimed the allotment policy of the Dawes Act (as later extended to apply to the Five Civilized Tribes through such devices as the Dawes Commission and the Curtis Act of 1898) was systematically manipulated to deprive the Native Americans of their lands and resources.[35] In the words of historian Ellen Fitzpatrick, Debo's book "advanced a crushing analysis of the corruption, moral depravity, and criminal activity that underlay white administration and execution of the allotment policy."[36]

See also

- Act for the Protection of the People of Indian Territory (Curtis Act), 1898

- Forced Fee Patenting Act (Burke Act), 1906

- Nelson Act of 1889, Minnesota's version of the Dawes Act

- Americanization of Native Americans

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- Land run

- Diminishment

Notes

- ↑ "General Allotment Act (or Dawes Act), Act of Feb. 8, 1887 (24 Stat. 388, ch. 119, 25 USCA 331), Acts of Forty-ninth Congress-Second Session, 1887". Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- 1 2 "Dawes Act (1887)". OurDocuments.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- ↑ "The Thirties in America: Indian Reorganization Act", Salem Press, Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ↑ Sandweiss, Martha A., Carol A. O’ Connor, and Clyde A. Milner II. The Oxford History of The American West, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. p. 174. Print.

- ↑ McDonnell, Janet. The Dispossession of the American Indian, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991. p. 1

- ↑ Carlson, Leonard A. Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land, Westport, Connecticut: 1981. p. 6. Print.

- ↑ Carlson, Leonard A. Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land, p. 1.

- ↑ Carlson, Leonard A. Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land, p. 5.

- ↑ Carlson, Leonard A. Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land. Westport, Connecticut: 1981. p. 79-80

- ↑ Sandweiss, Martha A., Carol A. O’ Connor, and Clyde A. Milner II. The Oxford History of The American West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. p. 174

- ↑ Carlson, Leonard A. Indians, Bureaucrats, and Land, Westport, Connecticut: 1981. p. 79

- ↑ McDonnell, Janet. The Dispossession of the American Indian. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991. p. 1.

- ↑ McDonnell, Janet. The Dispossession of the American Indian. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991. p. 2. Print.

- ↑ McDonnell, Janet. The Dispossession of the American Indian. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991. p. 3. Print.

- ↑ Otis, D.S. The Dawes Act and the Allotment of Indian Lands. Norman: U. of OK Press, 1973, pp. 5–6. Originally published in 1934.

- ↑ Dawes Act Sec. 6

- ↑ Dawes Act Sec. 7

- ↑ Dawes Act Sec. 8

- ↑ act of 1889, March 2, ch. 422 (post, p. 344)

- ↑ Otis, pp. 177–188

- ↑ "Dawes Severalty Act Amendments of 1891 (Statutes at Large 26, 794–96, NADP Document A1891)". Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Dawes Amendment Sec 1 and Sec 2

- ↑ Dawes Amendment Sec. 4

- ↑ Dawes Amendment Sec. 5

- ↑ "Burke Act (34 Stat. 182) Chapter 2348, May 8, 1906. [H. R. 11946.] [Public, No. 149.]". Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Terry L. Anderson, Property Rights Among Native Americans

- ↑ Kidwell, Clara Sue. "Allotment", Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (retrieved 29 December 2009)

- ↑ Gunn, Steven J. Major Acts of Congress:Indian General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) (1887). accessed 21 May 2011

- ↑ Otis, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Churchill, Ward. Struggle for Land: Native North American Resistance to Genocide, Ecocide and Colonization. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2002. p. 48. Print.

- ↑ Gibson, Arrell M. Gibson. "Indian Land Transfers." Handbook of North American Indians: History of Indian–White Relations, Volume 4. Wilcomb E. Washburn and William C. Sturtevant, eds. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1988. Pages 226–29

- ↑ Case DS, Voluck DA (2002). Alaska Natives and American Laws (2nd ed.). Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. pp. 104–5. ISBN 978-1-889963-08-2.

- ↑ Bartecchi D (2007-02-19). "The History of "Competency" as a Tool to Control Native American Lands". Pine Ridge Project. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Robertson, 2002

- ↑ Listing for And Still the Waters Run at Princeton University Press website (retrieved January 9, 2009).

- ↑ Ellen Fitzpatrick, History's Memory: Writing America's Past, 1880–1980 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-674-01605-X, p. 133, excerpt available online at Google Books.

Further reading

- Debo, Angie. And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1940; new edition, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984), ISBN 0-691-04615-8.

- Olund, Eric N. (2002). “Public Domesticity during the Indian Reform Era; or, Mrs. Jackson is induced to go to Washington.” Gender, Place, and Culture 9: 153-166.

- Stremlau, Rose. (2005). “To Domesticate and Civilize Wild Indians”: Allotment and the Campaign to Reform Indian Families, 1875-1887. Journal of Family History 30: 265-286.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dawes Act of 1887: full text from the Native American Documents Project

- Dawes Act (1887) Information & Videos - Chickasaw.TV

- Wheeler-Howard Act (Indian Reorganization Act) 1934

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory