Derecho

A derecho (/dəˈreɪtʃoʊ/, from Spanish: derecho [deˈɾetʃo], "straight") is a widespread, long-lived, straight-line wind storm that is associated with a land-based, fast-moving group of severe thunderstorms.[1]

Derechos can cause hurricane-force winds, tornadoes, heavy rains, and flash floods. Convection-induced winds take on a bow echo (backward "C") form of squall line, forming in an area of wind divergence in upper levels of the troposphere, within a region of low-level warm air advection and rich low-level moisture. They travel quickly in the direction of movement of their associated storms, similar to an outflow boundary (gust front), except that the wind is sustained and increases in strength behind the front, generally exceeding hurricane-force. A warm-weather phenomenon, derechos occur mostly in summer, especially during June, July, and August in the Northern Hemisphere, within areas of moderately strong instability and moderately strong vertical wind shear. They may occur at any time of the year and occur as frequently at night as during the daylight hours.

Etymology

Derecho comes from the Spanish word in adjective form for "straight" (or "direct"), in contrast with a tornado which is a "twisted" wind.[2] The word was first used in the American Meteorological Journal in 1888 by Gustavus Detlef Hinrichs in a paper describing the phenomenon and based on a significant derecho event that crossed Iowa on 31 July 1877.[3]

Development

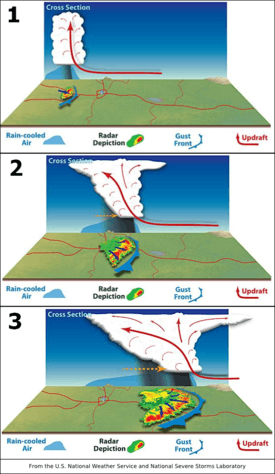

Organized areas of thunderstorm activity reinforce pre-existing frontal zones, and can outrun cold fronts. The resultant mesoscale convective system (MCS) forms at the point of the best upper level divergence in the wind pattern in the area of best low level inflow.[4] The convection then moves east and toward the equator into the warm sector, parallel to low-level thickness lines with the mean tropospheric flow. When the convection is strong linear or curved, the MCS is called a squall line, with the feature placed at the leading edge of the significant wind shift and pressure rise.[5]

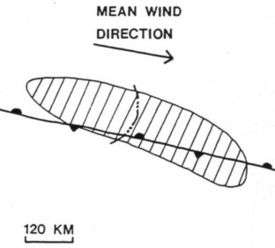

Derechos are squall lines that are bow- or spearhead-shaped on weather radar and, thus, also are called bow echoes or spearhead radar echoes. Squall lines typically bow out due to the formation of a mesoscale high pressure system which forms within the stratiform rain area behind the initial line. This high pressure area is formed due to strong descending motion behind the squall line, and could come in the form of a downburst.[6] The size of the bow may vary, and the storms associated with the bow may die and redevelop.

During the cold season within the Northern Hemisphere, derechos generally develop within a pattern of southwesterly winds at mid levels of the troposphere in an environment of low to moderate atmospheric instability (caused by heat and moisture near ground level or cooler air moving in aloft and measured by convective available potential energy) and high values of vertical wind shear (20 m/s (45 mph) within the lowest 5 kilometres (16,000 ft) of the atmosphere). Warm season derechos in the Northern Hemisphere form in west to northwesterly flow at mid levels of the troposphere with moderate to high levels of instability. Derechos form within environments of low-level warm air advection and significant low-level moisture.[7]

Classification and criteria

Its common definition is a thunderstorm complex that produces a damaging wind swath of at least 250 miles (400 km),[8] featuring a concentrated area of convectively-induced wind gusts exceeding 50 knots (60 mph; 90 km/h).[1] According to the National Weather Service criterion, a derecho is classified as a band of storms that have winds of at least 50 knots (90 km/h; 60 mph) along the entire span of the storm front, maintained over a time span of at least six hours. Some studies add a requirement that no more than two or three hours separate any two successive wind reports.[9] Derechos typically possess a high or rapidly increasing forward speed. They have a distinctive appearance on radar (known as a bow echo) with several unique features, such as the rear inflow notch and bookend vortices, and usually they manifest two or more downbursts.

There are four types of derechos:

- Serial derecho — This type of derecho is usually associated with a very deep low.

- Single-bow — A very large bow echo around or upwards of 250 miles (400 km) long. This type of serial derecho is less common than the multi-bow kind. An example of a single-bow serial derecho is the derecho that occurred in association with the October 2010 North American storm complex.

- Multi-bow — Multiple bow derechos are embedded in a large squall line typically around 250 miles (400 km) long. One example of a multi-bow serial derecho is a derecho that occurred during the 1993 Storm of the Century in Florida.[10] Because of embedded supercells, tornadoes can spin out of these types of derechos. This is a much more common type of serial derecho than the single-bow kind. Multi-bow serial derechos can be associated with line echo wave patterns on weather radar.

- Progressive derecho — A line of thunderstorms take the bow-shape and may travel for hundreds of miles along stationary fronts. An example of this is the Boundary Waters-Canadian Derecho of 4–5 July 1999. Tornado formation is less common in a progressive than serial type.

- Hybrid derecho — A derecho with characteristics of both a serial and progressive derecho. Similar to serial derechos and progressive derechos, these types of derechos are associated with a deep low, but are relatively small in size. An example is the Late-May 1998 tornado outbreak and derecho that moved through the central Northern Plains and the Southern Great Lakes on 30–31 May 1998.

- Low dewpoint derecho — A derecho that occurs in an environment of comparatively limited low-level moisture, with appreciable moisture confined to the mid-levels of the atmosphere. Such derechos most often occur between late fall and early spring in association with strong low pressure systems. Low dewpoint derechos are essentially organized bands of successive, dry downbursts. The Utah-Wyoming derecho of 31 May 1994 was an event of this type. It produced a 105 mph wind gust at Provo, Utah, where sixteen people were injured, and removed part of the roof of the Saltair Pavilion on the Great Salt Lake. Surface dewpoints along the path of the derecho were in the mid-40s °F.[11]

Characteristics

Winds in a derecho can be enhanced by downburst clusters embedded inside the storm. These straight-line winds may exceed 100 miles per hour (160 km/h), reaching 130 miles per hour (210 km/h) in past events.[12] Tornadoes sometimes form within derecho events, although such events are often difficult to confirm due to the additional damage caused by straight-line winds in the immediate area.[13]

With the average tornado in the United States and Canada rating in the low end of the F/EF1 classification at 85 to 100 miles per hour (137 to 161 km/h) peak winds and most or all of the rest of the world even lower, derechos tend to deliver the vast majority of extreme wind conditions over much of the territory in which they occur. Datasets compiled by the United States National Weather Service and other organizations show that a large swath of the north-central United States, and presumably at least the adjacent sections of Canada and much of the surface of the Great Lakes, can expect winds above 85 mph to as high as 120 mph (135 to 190 km/h) over a significant area at least once in any 50-year period, including both convective events and extra-tropical cyclones and other events deriving power from baroclinic sources. Only in 40 to 65 percent or so of the United States resting on the coast of the Atlantic basin, and a fraction of the Everglades, are derechos surpassed in this respect — by landfalling hurricanes, which at their worst may have winds as severe as EF3 tornadoes.[14]

Certain derecho situations are the most common instances of severe weather outbreaks which may become less favorable to tornado production as they become more violent; the height of 30–31 May 1998 upper Middle West-Canada-New York State derecho and the latter stages of significant tornado and severe weather outbreaks in 2003 and 2004 are only three examples of this. Some upper-air measurements used for severe-weather forecasting may reflect this point of diminishing return for tornado formation, and the mentioned three situations were instances during which the rare Particularly Dangerous Situation severe thunderstorm variety of severe weather watches were issued from the Storm Prediction Center of the U.S. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration.

Some derechos develop a radar signature resembling that of a hurricane in the low levels. They may have a central eye free of precipitation, with a minimum central pressure and surrounding bands of strong convection, but are really associated with an MCS developing multiple squall lines, and are not tropical in nature. These storms have a warm core, like other mesoscale convective systems. One such derecho occurred across the midwestern U.S. on 21 July 2003. An area of convection developed across eastern Iowa near a weak stationary/warm front and ultimately matured, taking on the shape of a wavy squall line across western Ohio and southern Indiana. The system re-intensified after leaving the Ohio Valley, starting to form a large hook, with occasional hook echoes appearing along its eastern side. A surface low pressure center formed and became more impressive later in the day.[15]

Location

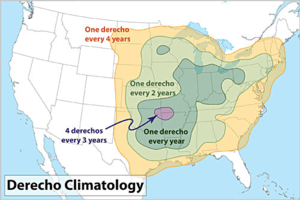

Derechos in North America form predominantly from April to August, peaking in frequency from May into July.[12] During this time of year, derechos are mostly found in the Midwestern United States most commonly from Oklahoma and across the Ohio Valley.[8] During mid-summer when a hot and muggy airmass covers the north-central U.S., they will often develop farther north into Manitoba or Northwestern Ontario, sometimes well north of the Canada–US border. North Dakota, Minnesota and upper Michigan are also vulnerable to derecho storms when such conditions are in place. They often occur along stationary fronts on the northern periphery of where the most intense heat and humidity bubble exists. Late-year derechos are normally confined to Texas and the Deep South, although a late-summer derecho struck upper parts of the New York State area after midnight on 7 September 1998. Warm season derechos have greater instability than their cold season counterpart, while cool season derechos have greater shear than their warm season counterpart.

Although these storms most commonly occur in North America, derechos can occur elsewhere in the world, although infrequently. Outside North America, they sometimes are called by different names. For example, in Bangladesh and adjacent portions of India, a type of storm known as a "Nor'wester" may be a progressive derecho.[1] One such event occurred on 10 July 2002 in Germany: a serial derecho killed eight people and injured 39 near Berlin. They have occurred in Argentina and South Africa as well, and on rarer occasions, close to or north of the 60th parallel in northern Canada. Primarily a mid-latitudes phenomenon, derechos do occur in the Amazon Basin of Brazil.[16] On 8 August 2010, a derecho struck Estonia and tore off the tower of Väike-Maarja Church.[17]

Damage risk

Unlike other thunderstorms, which typically can be heard in the distance when approaching, a derecho seems to strike suddenly. Within minutes, extremely high winds can arise, strong enough to knock over highway signs and topple large trees. These winds are accompanied by spraying rain and frequent lightning from all directions. It is dangerous to drive under these conditions, especially at night, because of blowing debris and obstructed roadways. Downed wires and widespread power outages are likely but not always a factor. A derecho moves through quickly, but can do much damage in a short time.

Since derechos occur during warm months and often in places with cold winter climates, people who are most at risk are those involved in outdoor activities. Campers, hikers, and motorists are most at risk because of falling trees toppled over by straight-line winds. Wide swaths of forest have been felled by such storms. People who live in mobile homes are also at risk; mobile homes that are not anchored to the ground may be overturned from the high winds. Across the United States, Michigan and New York have incurred a significant portion of the fatalities from derechos. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, the death tolls from derechos and hurricanes were comparable for the United States.[8]

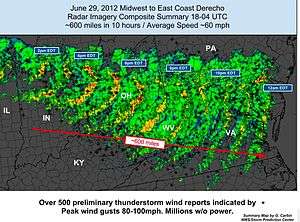

Derechos may also severely damage an urban area's electrical distribution system, especially if these services are routed above ground. The derecho that struck Chicago, Illinois on 11 July 2011 left more than 860,000 people without electricity.[18] The June 2012 North American derecho took out electrical power to more than 3.7 million customers starting in the Midwestern United States, across the central Appalachians, into the Mid-Atlantic States during a heat wave.[19]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Corfidi, Stephen F.; Johns, Robert H.; Evans, Jeffry S. (2013-12-03). "About Derechos". Storm Prediction Center, NCEP, NWS, NOAA Web Site. Retrieved 2014-01-08.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Spanish/English Dictionary (2009). Derecho. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved on 2009-05-03.

- ↑ Wolf, Ray (2009-12-18). "A Brief History of Gustavus Hinrichs, Discoverer of the Derecho". National Weather Service Central Region Headquarters. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- ↑ Schaefer, Joseph T. (December 1986). "Severe Thunderstorm Forecasting: A Historical Perspective". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 1 (3): 164–189. Bibcode:1986WtFor...1..164S. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1986)001<0164:STFAHP>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology (2008). "Chapter 2: Definitions" (PDF). NOAA. pp. 2–1. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ Parke, Peter S. and Norvan J. Larson (2005). Boundary Waters Windstorm. National Weather Service Forecast Office, Duluth, Minnesota. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Burke, Patrick C.; Schultz, David M. (2004). "A 4-Yr Climatology of Cold-Season Bow Echoes over the Continental United States". Weather and Forecasting. 19 (6): 1061–1069. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19.1061B. doi:10.1175/811.1.

- 1 2 3 Ashley, Walker S.; Mote, Thomas L. (2005). "Derecho Hazards in the United States". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 86 (11): 1580–1585. Bibcode:2005BAMS...86.1577A. doi:10.1175/BAMS-86-11-1577.

- ↑ Coniglio, Michael C.; Stensrud, David J. (2004). "Interpreting the Climatology of Derechos". Weather and Forecasting. 19 (3): 595. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19..595C. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2004)019<0595:ITCOD>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- ↑ Storm Prediction Center (4 August 2004). "Summary of the Subtropical Derecho". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ↑ Corfidi, Stephen F. "The Utah-Wyoming derecho of May 31, 1994". Storm Prediction Center, NCEP, NWS, NOAA Web Site. Retrieved 2014-01-08.

- 1 2 Brandon Vincent and Ryan Ellis (Spring 2013). "Understanding a Derecho: What is it?" (PDF). Changing Skies over Central North Carolina. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 10 (1): 1–7. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ↑ "Derecho". XWeather.org. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "What was the Largest Hurricane to Hit the United States?". Geology.com. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ David M. Roth. MCS with Eye - 21 July 2003. Retrieved on 2008-01-08.

- ↑ Negrón-Juárez, Robinson I.; Chambers, Jeffrey Q.; Guimaraes, Giuliano; Zeng, Hongcheng; Raupp, Carlos F. M.; Marra, Daniel M.; Ribeiro, Gabriel H. P. M.; Saatchi, Sassan S.; et al. (2010). "Widespread Amazon forest tree mortality from a single cross-basin squall line event". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (16): 16701. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3716701N. doi:10.1029/2010GL043733.

- ↑ (Estonian) http://www.ilm.ee/index.php?47736[]

- ↑ Janssen, Kim, Mitch Dudek and Stefano Esposito, "Storm could break ComEd record with 860,000-plus losing power," Chicago Sun-Times, 11 July 2011.

- ↑ Simpson, Ian (2012-06-30). "Storms leave 3.4 million without power in eastern U.S.". Chicago Tribune. Reuters. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

Further reading

- Ashley, Walker S., et al. (2004). "Derecho Families". Proceedings of the 22nd Conference on Severe Local Storms, American Meteorological Society, Hyannis, MA.

- Ashley, Walker S.; Mote, Thomas L.; Bentley, Mace L. (2005). "On the episodic nature of derecho-producing convective systems in the United States". International Journal of Climatology. 25 (14): 1915. Bibcode:2005IJCli..25.1915A. doi:10.1002/joc.1229.

- Bentley, Mace L.; Mote, Thomas L. (1998). "A Climatology of Derecho-Producing Mesoscale Convective Systemsin the Central and Eastern United States, 1986–95. Part I: Temporal and Spatial Distribution". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 79 (11): 2527. Bibcode:1998BAMS...79.2527B. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079<2527:ACODPM>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- Bentley, Mace L.; Mote, Thomas L.; Byrd, Stephen F. (2000). "A synoptic climatology of derecho producing mesoscale convective systems in the North-Central Plains". International Journal of Climatology. 20 (11): 1329. Bibcode:2000IJCli..20.1329B. doi:10.1002/1097-0088(200009)20:11<1329::AID-JOC537>3.0.CO;2-F.

- Coniglio, Michael C.; Stensrud, David J.; Richman, Michael B. (2004). "An Observational Study of Derecho-Producing Convective Systems". Weather and Forecasting. 19 (2): 320. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19..320C. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2004)019<0320:AOSODC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- Coniglio, Michael C.; Corfidi, Stephen F.; Kain, John S. (2011). "Environment and Early Evolution of the 8 May 2009 Derecho-Producing Convective System". Monthly Weather Review. 139 (4): 1083. Bibcode:2011MWRv..139.1083C. doi:10.1175/2010MWR3413.1.

- Corfidi, Stephen F.; Corfidi, Sarah J.; Imy, David A.; Logan, Alan L. (2006). "A Preliminary Study of Severe Wind-Producing MCSs in Environments of Limited Moisture". Weather and Forecasting. 21 (5): 715. Bibcode:2006WtFor..21..715C. doi:10.1175/WAF947.1.

- Doswell, Charles A. (1994). "Extreme Convective Windstorms: Current Understanding and Research". In Corominas, Jordi; Georgakakos, Konstantine P. Report of the Proceedings of the US–Spain Workshop on Natural Hazards (8–11 June 1993, Barcelona, Spain). pp. 44–55. OCLC 41154867.

- Doswell, Charles A.; Evans, Jeffry S. (2003). "Proximity sounding analysis for derechos and supercells: An assessment of similarities and differences". Atmospheric Research. 67-68: 117. Bibcode:2003AtmRe..67..117D. doi:10.1016/S0169-8095(03)00047-4.

- Evans, Jeffry S.; Doswell, Charles A. (2001). "Examination of Derecho Environments Using Proximity Soundings". Weather and Forecasting. 16 (3): 329. Bibcode:2001WtFor..16..329E. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2001)016<0329:EODEUP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- Johns, Robert H.; Hirt, William D. (1987). "Derechos: Widespread Convectively Induced Windstorms". Weather and Forecasting. 2: 32. Bibcode:1987WtFor...2...32J. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1987)002<0032:DWCIW>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- Przybylinski, Ron W. (1995). "The Bow Echo: Observations, Numerical Simulations, and Severe Weather Detection Methods". Weather and Forecasting. 10 (2): 203. Bibcode:1995WtFor..10..203P. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1995)010<0203:TBEONS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

External links

- Facts about derechos (Storm Prediction Center's "About Derechos" web page; Stephen Corfidi with Robert Johns and Jeffry Evans)

- What is a derecho? (University of Nebraska at Lincoln)

- What is a derecho? (Meteorologist Jeff Haby's education page)

- Derecho Hazards in the United States (Walker Ashley)

- Origin of the term "Derecho" as a Severe Weather Event (Meteorologist Robert Johns)

- A Mediterranean derecho: Catalonia(Spain), 17 th August 2003 (ECSS 2003, León, Spain, 9–12 November 2004)

- American Museum of Natural History Science Bulletins: Derecho December 2003