Empire Builder

|

The Empire Builder crosses the Two Medicine Trestle at East Glacier Park, Montana in 2011. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service type | Inter-city rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First service | June 11, 1929 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last service | present | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current operator(s) | Amtrak (1971–present) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former operator(s) |

Great Northern Railway (1929–1970) Burlington Northern Railway (1970–1971) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 1,285 daily | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual ridership | 469,167 total (FY11)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End |

Portland, Oregon Seattle, Washington | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance travelled |

2,206 miles (3,550 km) (Chicago - Seattle) 2,257 miles (3,632 km) (Chicago - Portland) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service frequency | Daily | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train number(s) |

7 (Chicago-Spokane-Seattle) 8 (Seattle-Spokane-Chicago) 27 (Chicago-Spokane-Portland) 28 (Portland-Spokane-Chicago) 807 (Chicago-St. Paul) 808 (St. Paul-Chicago) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | Superliner sleepers and coaches | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed |

79 mph (127 km/h) max 50 mph (80 km/h) average | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track owner(s) |

BNSF Railway (Seattle - Minneapolis) Minnesota Commercial Railway (Minneapolis - St. Paul) Canadian Pacific (St. Paul - Glenview) Metra (Glenview - Chicago) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Empire Builder is a daily passenger train operated by Amtrak in the Midwestern and Northwestern United States. It is Amtrak's busiest long-distance route, running from Chicago to the Pacific Northwest. The line splits into two segments in Spokane, Washington; its northern segment terminates at King Street Station in Seattle while its southern segment terminates at Union Station in Portland.

The end-to-end travel time for the route is 45 to 46 hours, averaging 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) including stops, though track conditions allow the train to travel up to 79 miles per hour (127 km/h) for the majority of the route.

History

On June 11, 1929, the Great Northern Railway inaugurated the Empire Builder in honor of the company's founder, James J. Hill. Known as "The Empire Builder," Hill had reorganized several failing railroads into a transcontinental railroad that reached the Pacific Northwest in the late 19th century.[2] Following World War II, Great Northern placed new streamlined and diesel-powered trains in service that cut the scheduled 2,211 miles between Chicago and Seattle from 58.5 hours to 45 hours.[3]

The schedule allowed riders views of the Cascade Mountains and Glacier National Park, a park established through the lobbying efforts of the Great Northern. Re-equipped with domes in 1955, the Empire Builder offered passengers sweeping views of the route through three dome coaches and one full-length Great Dome car for first class passengers.[4]

In 1970, the Great Northern merged with other railroads to form the Burlington Northern Railroad, which assumed operation of the Builder. One year later, Amtrak assumed operation of the train and shifted the Chicago to St. Paul leg to the Milwaukee Road route through Milwaukee along the route to St Paul.[5]

The route between Chicago and Spokane has remained somewhat consistent, but the split into Seattle and Portland sections disappeared between 1971 and 1981, when there was no Portland section. The Spokane-Portland section of the train was operated by the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway.[6] Before 1971, the Chicago to St. Paul leg was operated via the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad's mainline along the Mississippi River through Wisconsin. The service also used to operate west from the Twin Cities before turning north in Willmar, Minnesota, to reach Fargo.

In 2005, Amtrak upgraded service to include a wine and cheese tasting in the dining car for sleeping-car passengers and free newspapers in the morning.[7] Amtrak's inspector general eliminated some of these services in 2013 as part of a cost-saving measure.[8]

During summer months, on portions of the route, "Trails and Rails" volunteers in the lounge car comment on points of visual and historic interest that can be viewed from the train.[9]

Ridership

| Annual Passenger Ridership and Revenue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY* | Ridership | % Change | Revenue | % Change |

| 2004 | 437,191 | - | $39,130,724 | - |

| 2005 | 476,531 | +9.0% | $42,131,741 | +7.7% |

| 2006 | 497,020 | +4.3% | $48,695,783 | +15.1% |

| 2007 | 504,977 | +1.6% | $53,177,760 | +9.2% |

| 2008 | 554,266 | +9.8% | $59,461,168 | +11.8% |

| 2009 | 515,444 | -7.0% | $54,064,861 | -9.0% |

| 2010 | 533,493 | +3.5% | $58,497,143 | +8.2% |

| 2011 | 469,167 | -12.1% | $53,773,711 | -8.1% |

| 2012 | 543,072 | +15.8% | $66,655,153 | +24.0%% |

| 2013 | 536,391 | -1.2% | $67,394,779 | +1.1% |

| 2014 | 450,932 | -15.9% | $54,545,844 | -19.1% |

| 2015 | 438,376 | -2.8% | $50,541,140 | -7.3% |

| 2016 | 454,625 | +3.7% | $51,798,583 | +2.5% |

| Sources:[10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22]

- Denotes unavailable data. | ||||

The Empire Builder is the most popular long-distance train in the Amtrak system. About 65% of the cost of operating the train is covered by fare revenue, a rate among Amtrak's long-distance trains second only to the specialized East Coast Auto Train.[23]

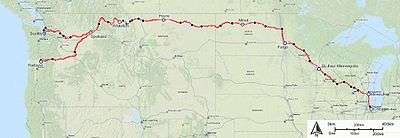

Route

The train passes through Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois. It makes service stops in Spokane, Washington, Havre, Montana, Minot, North Dakota, and Saint Paul, Minnesota. Its other major stops include Vancouver, Washington, Whitefish, Montana, Fargo, North Dakota, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It uses BNSF Railway's northern route from Seattle to Minneapolis, Minnesota Commercial from Minneapolis to St. Paul, Canadian Pacific from St. Paul to Glenview, and Metra from Glenview to Chicago.

From Seattle, the northern segment uses the Cascade Tunnel and Stevens Pass as it traverses the Cascades Range to reach Spokane, while the southern segment departs Portland and runs along the north side of the Columbia River Gorge. The eastbound cars merge into one train at Spokane. The train continues into the mountains in eastern Washington and northern Idaho. Amtrak organizes the schedule so the train will pass through the Rocky Mountains (and Glacier National Park) during daylight, but this is more likely on the eastbound train during summer. Passengers can see sweeping views as the train skirts the southern edge of the park, crossing the Continental Divide at Marias Pass.

After three short stops near Glacier National Park—(East Glacier Park [summer only] or Browning [winter only]); Essex [a flag stop]; and West Glacier Park)—it makes a longer stop in Whitefish, Montana before entering the Northern Plains of eastern Montana and North Dakota. The land changes from prairie to forest as it travels through Minnesota. From Saint Paul Union Depot, the train crosses the Mississippi River at Hastings, Minnesota and passes through southeastern Minnesota cities on or near Lake Pepin before crossing the Mississippi again at La Crosse, Wisconsin. It winds through rural southern Wisconsin, turns south at Milwaukee, and ends at Chicago Union Station.

Flooding

The line has come under threat from flooding from the Missouri, Souris, Red, and Mississippi Rivers, and has occasionally had to suspend or alter service. Most service gets restored in days or weeks, but Devils Lake in North Dakota, which has no natural outlet, is a long-standing threat. The lowest top-of-rail elevation in the lake crossing is 1,455.7 ft (443.70 m).[24] In spring 2011, the lake reached 1,454.3 ft (443.27 m),[25] causing service interruptions on windy days when high waves threatened the tracks.

BNSF, which owns the track, suspended freight operations through Devils Lake in 2009 and threatened to allow the rising waters to cover the line unless Amtrak could provide $100 million to raise the track. In that case, the Empire Builder would have been rerouted to the south, ending service to Rugby, Devils Lake, and Grand Forks.[26] In June 2011 agreement was reached that Amtrak and BNSF would each cover 1/3 of the cost with the rest to come from the federal and state governments.[27]

In December 2011 the state of North Dakota was awarded a $10 million TIGER grant from the US Department of Transportation to assist with the state portion of the cost.[28] Work began in June 2012, and the track is being raised in two stages: 5 feet in 2012, and another 5 feet in 2013. Two bridges and their abutments are also being raised. When the track raise is complete, the top-of-rail elevation will be 1,466 ft (446.84 m).[29] This is 10 feet above the level at which the lake will naturally overflow and will thus be a permanent solution to the Devils Lake flooding. In the spring and summer of 2011 flooding of the Souris River near Minot, North Dakota blocked the route in the latter part of June and for most of July. For some of that time the Empire Builder (with a typical consist of only four cars) ran from Chicago and terminated in Minneapolis/St Paul; to the west, the Empire Builder did not run east of Havre, Montana. (Other locations along the route also flooded, near Devils Lake, North Dakota and areas further west along the Missouri River.)

Freight train interference

An oil boom from the Bakken formation, combined with a robust fall 2013 harvest, led to a spike in the number of crude oil and grain trains using the BNSF tracks in Montana and North Dakota. The resulting congestion led to terrible delays for the Empire Builder, with the train receiving a 44.5% on-time record for November 2013, the worst rating on the Amtrak network. In some cases, the delays resulted in an imbalance of crew and equipment, forcing Amtrak to cancel runs of the Empire Builder.[30] In May 2014, only 26% of Empire Builder trains had arrived within 30 minutes of their scheduled time, and delays averaged between 3 and 5 hours.[31]

Owing to the routine delays, which had become severe, Amtrak officially changed the scheduled times for station stops west of Minneapolis, taking effect on April 15, 2014. The rescheduled times were designed to keep the same departure/arrival times in Chicago and through the corridor up to and including Minneapolis. However, scheduled stops westbound out of Minneapolis were set for later times, while eastbound, the train departed Seattle/Portland approximately three hours earlier than previously. Operating hours for affected stations were also officially adjusted accordingly. The Amtrak announcement also said that the BNSF Railway was working on adding track capacity, and it was anticipated that sometime in 2015 the Empire Builder could be returned to its former schedule. In January 2015, it was announced that the train would resume its normal schedule.[32]

Former stops

In 1970 the flooding of Lake Koocanusa necessitated the realignment of 60 miles of track and the construction of Flathead Tunnel forcing the Empire Builder to drop service to Eureka, Montana. The Empire Builder also served Troy, Montana until February 15, 1973. On October 1, 1979, Amtrak moved the Empire Builder to operate over the North Coast Hiawatha's old route between Minneapolis and Fargo, North Dakota. With this alignment change, the Empire Builder dropped Willmar, Minnesota, Morris, Minnesota, and Breckenridge, Minnesota, while adding St. Cloud, Minnesota, Staples, Minnesota, and Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. Another alignment change came on October 25, 1981, when the Seattle section moved from the old Northern Pacific (which had also become part of the BN Railroad in 1970) to the Burlington Northern Railroad's line through the Cascade Tunnel over Stevens Pass. This change eliminated service to Yakima, Washington, Ellensburg, Washington, and Auburn, Washington.[33] This change also marked the inauguration of the Portland section of the Builder, which returned service to the former Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railroad (it, too, became part of the BN system in 1970) line along the Washington side of the Columbia River to Portland. The route kept Pasco, but added Wishram, Bingen-White Salmon, and Vancouver (all in Washington) to the route. From Vancouver, the Builder followed the same route as the Coast Starlight and Cascades trains to Portland Union Station.

It is proposed that the Empire Builder and Hiawatha Service trains would shift one stop north to North Glenview in Glenview, Illinois. This move would eliminate stops which block traffic on Glenview Road. The North Glenview station would have to be modified to handle additional traffic, and the move depends on commitments from Glenview, the Illinois General Assembly and Metra.[34] In Minnesota, the Builder returned to Saint Paul Union Depot on May 7, 2014, 43 years after it last served the station the day before the start of Amtrak. Renovation of the 1917 Beaux Arts terminal was undertaken in 2011, continuing through 2013, resulting in a multi-mode terminal now in use by Jefferson Bus Lines, Greyhound Bus lines, commuter bus and soon commuter rail and light rail from Minneapolis.[35] The station replaced Midway Station which opened in 1978 after the initial abandonment of Saint Paul Union Depot in 1971 and the demolition of Minneapolis Great Northern Depot in 1978.

A new stop is in planning for the town of Culbertson, Montana, which is about halfway between the stops of Williston, North Dakota and Wolf Point, Montana. This stop will mainly be to serve the rapidly growing oil regions of northwestern North Dakota and northeastern Montana. The former Great Northern depot and platform still exist in Culbertson, however the station will need some major renovation and the platform will need to be lengthened and upgraded.

Equipment used

| July 4, 1963 | |

|---|---|

| Train | Eastbound |

| |

Current equipment used

Like all long-distance trains west of the Mississippi River, the Empire Builder uses Amtrak's double-deck Superliner equipment. The Empire Builder was the first train to be fully equipped with Superliners, with the first run occurring on October 28, 1979.[37] In Summer, 2005 the train was "re-launched" with newly refurbished equipment.

During typical service, an Empire Builder comprises the following (with destinations after Spokane in parentheses:)

- Two GE P42 "Genesis" Locomotives

- Baggage car (Seattle)

- Transitional Crew Sleeper (Seattle)

- Sleeper (Seattle)

- Sleeper (Seattle)

- Diner (Seattle)

- Coach (Seattle)

- Coach (Seattle)

- Sightseer Lounge/Café (Portland)

- Coach/Baggage (Portland)

- Coach (Portland)

- Sleeper (Portland)

- Coach (Chicago - St Paul) - This car is train number 807/808.

In Spokane the train is split into two pieces. The locomotives along with the baggage car and first six passenger cars continue onto Seattle. A single P42 is stored in Spokane, which picks up the last four cars to transport them to Portland. The opposite of this happens going eastbound. During peak travel periods, an additional coach is attached to the very rear end of the train between Chicago and St. Paul. It is left at St. Paul for the next day's return trip to pick up. This car is signed as train number "807/808", while the cars in the Portland segment are signed as train 27/28, and the Seattle segment is signed as train 7/8. This adds capacity during especially busy times in the year.

Historical equipment used

Car ownership on this train was by-and-large split between the Great Northern and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), though a couple of cars in the original consists were owned by the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway (SP&S). In this consist, one of the 48-seat "chair" cars and one of the 4-section sleepers were used for the connection to Portland, while the rest of the consist connected to Seattle.

The Great Northern coaches eventually found their way into state-subsidized commuter service for the Central Railroad of New Jersey after the Burlington Northern merger and remained until 1987 when NJ Transit retired its last E8A locomotive. Some of these cars remain in New Jersey. Some coaches were acquired from the Union Pacific; these also went to New Jersey. One of the 28 seat coach-dinette cars also remains in New Jersey and is stored near Interstate 78 wearing tattered Amtrak colors.

Notes

- ↑ "Amtrak Ridership Rolls Up Best-Ever Records" (PDF). Amtrak. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ↑ Hidy et al. 2004, p. 180

- ↑ Hidy et al. 2004, p. 244

- ↑ Hidy et al. 2004, p. 272

- ↑ "Empire Builder Timeline". Great Northern Timeline. Great Northern Railway Historical Society. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "Through Your Car Window - Westbound - On the Streamlined Empire Builder, Western Star and other Great Northern Trains". Great Northern Railway Page. Great Northern Railway. June 1953. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ↑ "Amtrak Empire Builder Relaunch". Amtrak Empire Builder. trainweb.com. August 1, 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- ↑ "To See Why Amtrak's Losses Mount, Hop on the Empire Builder Train". msn.com. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "Trails & Rails". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ "2016 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- ↑ "2015 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2014 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2013 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2012 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2011 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2010 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2006-2009 ridership" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2005-2006 Revenue" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2007-2008 Revenue" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "2005 ridership" (PDF). PR Newswire. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "2004-2006 Revenue" (PDF) (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "2004 ridership" (PDF). Amtrak. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "North Coast Hiawatha Passenger Rail Study" (PDF). Amtrak. October 16, 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ↑ "Railroad Grade Raise Planning and Feasibility Study" (PDF). April 8, 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ↑ "Devils Lake Gauge at Creel Bay". Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ↑ "Devils Lake threatens Empire Builder". KFGO. April 23, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "Amtrak Service To Continue". WDAZ. June 15, 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ↑ "ND Leaders Review Strategy to Raise DL Rail Line". February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ↑ Bonham, Kevin. "Railroad raising underway in Devils Lake area". Grand Forks Herald. Bakken Today. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Tate, Curtis (December 23, 2013). "Freight trains force repeated delays on popular Amtrak route". Seattle Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ McCartney, Scott (June 18, 2014). "Amtrak Sees Delays Increase". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Amtrak's Empire Builder back on schedule". Great Falls Tribune. January 13, 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ Sanders 2006, pp. 163–172

- ↑ "Amtrak eyes moving Ill. station". Railway Track & Structures. November 11, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ Black, Sam (December 10, 2009). "Mortenson team picked for $150M St. Paul Union Depot transit hub". Minneapolis / St. Paul Business Journal. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ↑ Dubin, Arthur, D (1964). Some Classic Trains. Milwaukee: Kalmbach. p. 309.

- ↑ "Superliners Go Into Service On Empire Builder Route". Amtrak NEWS. 6 (12): 1. November 1979.

References

- Hidy, Ralph W.; et al. (2004) [1988]. The Great Northern Railway: A History. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. ISBN 978-0-816-64429-2. OCLC 54885353.

- Sanders, Craig (2006). Amtrak in the Heartland. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34705-X. OCLC 61499942.

- Wayner, Robert J., ed. (1972). Car Names, Numbers and Consists. New York: Wayner Publications. OCLC 8848690.

- Yenne, Bill (2005). Great Northern Empire Builder. Great Passenger Trains. MBI. ISBN 0-7603-1847-6. OCLC 57142776.

Further reading

- Morgan, David P. (2016). "The Clean-Window Train". In McGonigal, Robert S. Great Trains West. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 96–107. ISBN 978-1-62700-435-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empire Builder. |

-

Empire Builder travel guide from Wikivoyage

Empire Builder travel guide from Wikivoyage - Amtrak — Empire Builder

- Empire Builder 75th Anniversary page

- Brochures and History of GN's Empire Builder

- Information and photos of GN's Empire Builder equipment

.jpg)