Ernst von Bibra

| Ernst von Bibra | |

|---|---|

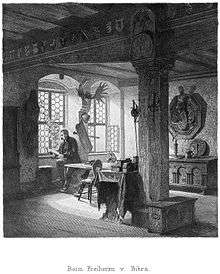

|

Engraving by Weger | |

| Born |

9 June 1806 Schwebheim, Franconia Present day Bavaria, Germany |

| Died |

5 June 1878 (aged 71) Nuremberg, Bavaria |

| Residence | Schwebheim and Nuremberg |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | natural history, botany, zoology, metallurgy, ethnopsychopharmacology |

| Alma mater | Neuberg on the Danube, University of Würzburg |

| Known for | Studies of plant intoxicants, animal experimentation, metallurgy of historical objects, grains, anesthesia., art and artifact collector, novelist |

| Influenced | Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann |

Dr. Ernst Freiherr von Bibra (9 June 1806 in Schwebheim – 5 June 1878 in Nuremberg) was a German Naturalist (Natural history scientist) and author. Ernst was a botanist, zoologist, metallurgist, chemist, geographer, travel writer, novelist, duellist, art collector and trailblazer in ethnopsychopharmacology.

Biography

Ernst's father, Ferdinand Johann von Bibra, (*1756; † 1807), fought under General Rochambeau in the American Revolutionary War on behalf of the colonies. Later he married his brother's daughter, Lucretia Wilhelmine Caroline von Bibra,(1778. + 1857). Ernst's father died when he was 1½ years old and Baron Christoph Franz von Hutten (d. 1830) raised Ernst in Würzburg. He graduated at nineteen from a boarding school in Neuberg on the Danube. Baron Ernst von Bibra started studying law at Würzburg but soon changed over to the natural sciences, especially chemistry. ("Dr. med. & phil." Doctor of medicine & PhD) Martin Haseneier, in his Foreword to the 1995 translation Plant Intoxicants relates that Ernst fought in no less than 49 duels as a young man! Six of his works have been reprinted in recent years. Besides the castle and estate at Schwebheim, Ernst was the owner of a half interest in the castle and estate at Willershausen (Herleshausen). Ernst sold his half of the castle and estate of Willershausen (Herleshausen) in 1850 to the Landgrave Carl August of Hesse.

He produced: Chemical Research on Various Varieties of Pus (Berlin 1842); Chemical Research on the Bones and Teeth of Humans and Other Vertebrates (Schweinfurt 1844) and Helpful Tables for the Recognition of the Substances of Zoological Chemistry (Erlangen 1846). Then in cooperation with Geist he published: Investigations of the Diseases of the Workers in the Phosphorus Match Factories (Erlangen 1847) as well as with Harleß The Events of the Investigations of the Effects of Sulphur Fumes (Erlangen 1847). After he had published Chemical Fragments Concerning the Liver and Gall-Bladder (Braunschweig 1849), he went to Brazil and around Cape Horn. He reported on this trip in his Trips in South America (Mannheim 1854, 2 vols.). After his return he lived mostly in Nuremberg where he also set up his rich collections of natural history ethnographics and died on 5 June 1878. Here he published Comparative Investigations of the Human Brain and Those of Other Vertebrates (Mannheim 1854); The Narcotic Substances of Enjoyment and the Human Being (Nuremberg 1855); Bread and the Various Grains (Nuremberg 1860); Coffee and its Substitute (Reports at the Meetings of the Academy of Sciences in Munich, 1858); The Bronze and Copper Alloys of the Old and Most Ancient Peoples (Erlangen 1869) and Concerning Old Discoveries of Iron and Silver (Nuremberg 1873).

Ernst work on narcotics is his most famous and was recently translated into English and publish under the name of Plant Intoxicants. (ISBN 0-89281-498-5). This was one of the first books to examine the cultivation, preparation, and consumption of the world’s major stimulants and inebriants. The book includes seventeen chapters : 1) coffee, 2)coffee leaves as a beverage 3) tea, 4) Paraguayan Tea (yerba maté), 5) Guarana, 6) chocolate, 7) Fahan Tea (the orchid Angraecum fragrans Thouars as a source of coumarin), 8) Khat, 9) Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria) opiate derived from the "poison lettuce,"10) thorn apple, 11) coca, 12) opium, 13) Lactucarium 14) hashish, 15) tobacco 16) Betel and Related Substances (Areca catechu, areca nut; Piper siriboa, the betel leaf) and 17) arsenous acid or arsenic trioxide (As2O3). Because of Ernst's early investigation and writing on coffee, he is occasionally referenced in modern coffee literature.

Starting with travel sketches and culturally historic descriptions rendered in novelistic style (Memories of South America, Leipzig 1861, 3 vols.; About Chile, Peru and Brazil, Leipzig 1862, 3 vols. and others) von Bibra preferred to busy himself in his later years with fictional works and developed an astonishing fruitfulness in this field. Of these writings which stand out especially because of successful characterizations and descriptions of beautiful landscapes we mention: A Jewel (Leipzig 1863); A Woman with a Noble Heart (Ein edles Frauenherz was featured in a radio broadcast on 26 August 2006 reading and concert)(2nd ed., Jena 1869); The Adventures of a Young Peruvian in Germany (Jena 1870); The Nine Stations of Mr. von Scherenberg (2nd ed. Jena 1880); The Children of the Rogue:(Nuremberg 1872); Brave Women (Jena 1876.)

Honors

Germany:

- Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina renamed in 2007 "German Academy of Sciences" (Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften) 1844

- Verdienstorden vom Heiligen Michael (Order of Merit of Saint Michael) 1854

- Preuss. Roter Adler Orden IV. Klasse (Order of the Red Eagle 4th Class, Knight) 1854

- Preuss. Kronorden III Klasse (Order of the Crown (Prussia), 3rd Class) 1869

Russia:

- Received Honor from Czar Alexander II of Russia in 1860 for work with grains.

von Bibra Family

Ernst was a member of the aristocratic Franconian von Bibra family which among its members were Lorenz von Bibra, Prince-Bishop of Würzburg, Duke in Franconia (1459–1519), Lorenz’ half brother, Wilhelm von Bibra Papal emissary, Conrad von Bibra, Prince-Bishop of Würzburg, Duke in Franconia (1490–1544) and Heinrich von Bibra, Prince-Bishop, Prince-Abbot of Fulda (1711–1788).

Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Ernst was one of the co-founders of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (formerly "Germanischen Museums“) located in Nuremberg. Founded in 1852, led by close friend and fellow Franconian baron, Hans von und zu Aufsess, whose goal was to assemble a "well-ordered compendium of all available source material for German history, literature and art". Ernst donated much of his personal collection, which included art, a rich natural history and ethnographic collection, to the museum. The "Bibra-Stube" was installed in the museum in 1887–1888.

"Theory on the action of ether" Anesthesia

An outdated theory of anaesthetic action, Ernst von Bibra and Emil Harless, in 1847, were the first to suggest that general anaesthetics may act by dissolving in the fatty fraction of brain cells. They proposed that anaesthetics dissolve and remove fatty constituents from brain cells, changing their activity and inducing anaesthesia. Below is the abstract of a recent German scientific paper on their work.

- Frühe Erlanger Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der äther- und Chloroformnarkose : Die tierexperimentellen Untersuchungen von Ernst von Bibra und Emil Harless U. v. Hintzenstern, H. Petermann, W. Schwarz Der Anaesthesist Issue Volume 50, Number 11 / November, 2001

Abstract of Article:

Just three months after the first application of sulphuric ether to a patient in German-speaking countries the monography Die Wirkung des Schwefeläthers in chemischer und physiologischer Beziehung was published. In this book Ernst von Bibra and Emil Harless presented their experimental research on the effects of ether on humans and compared it to those on animals. The contents of the book are described. The authors "Theory on the action of ether" will be discussed in the context of contemporary criticism. Their hypothesis affected the discussion on the mechanisms of anaesthetic action up to the twentieth century.

Composition of Barley

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1910–1911) cites the following composition of barley meal according to Ernst von Bibra, omitting the salts:[1]

Water 15% Nitrogenous compounds 12.981% Gum 6.744% Sugar 3.200% Starch 59.950% Fat 2.170%

What others thought about Ernst von Bibra

Richard Evans Schultes, "Father of Modern Ethnobotany" on Ernst von Bibra

Richard Evans Schultes, Ph.D., F.L.S. who was the Curator of Economic Botany and Executive Director, Harvard Botanical Museum wrote in The plant kingdom and hallucinogens (1970):

- In 1855, Ernst Freiherr von Bibra published the first book of its kind, Die narkotischen Genussmittel und der Mensch, in which he considered some 17 plant narcotics and stimulants and urged chemists to study assiduously a field so promising for research and so fraught with enigmas.

- A review of the scientific literature of the last half of the past century indicates that von Bibra's suggestions were followed, and an interdisciplinary interest in narcotics began to take hold and grow. It proved to be the spark that eventually engendered today's extraordinarily extensive and complex literature in many fields on narcotic substances.

- Half a century later, in 1911, another outstanding book-in reality, a much expanded and modernized successor of von Bibra's work-appeared in C. Hartwich's Die menschlichen Genussmittel. This volume considered at great length and with interdisciplinary emphasis about 30 vegetal narcotics and stimulants and mentioned many others in passing. Hartwich pointed out that von Bibra's pioneer work was out of date, that research on the botanical aspects and chemical constituents of these curiously active plants had, in 1855, scarcely begun but that, by 1911, such studies were either progressing well or had already been completed.

Albert Hofmann on Ernst von Bibra

Albert Hofmann writes and quotes Ernst in his book LSD — My Problem Child, Chapter 7. "Radiance from Ernst Jünger"

- I visited Ernst Jünger occasionally in the following years, in Wilfingen, Germany, where he had moved from Ravensburg; or we met in Switzerland, at my place in Bottmingen, or in Bundnerland in southeastern Switzerland. Through the shared LSD experience our relations had deepened. Drugs and problems connected with them constituted a major subject of our conversation and correspondence, without our having made further practical experiments in the meantime.

- We exchanged literature about drugs. Ernst Jünger thus let me have for my drug library the rare, valuable monograph of Dr. Ernst Freiherrn von Bibra, Die Narkotischen Genussmittel und der Mensch [Narcotic pleasure drugs and man] printed in Nuremberg in 1855. This book is a pioneering, standard work of drug literature, a source of the first order, above all as relates to the history of drugs. What von Bibra embraces under the designation "Narkotischen Genussmittel" are not only substances like opium and thorn apple, but also coffee, tobacco, khat, which do not fall under the present conception of narcotics, any more than do drugs such as coca, fly agaric, and hashish, which he also described.

- Noteworthy, and today still as topical as at the time, are the general opinions about drugs that von Bibra contrived more than a century ago: The individual who has taken too much hashish, and then runs frantically about in the streets and attacks everyone who confronts him, sinks into insignificance beside the numbers of those who after mealtime pass calm and happy hours with a moderate dose; and the number of those who are able to overcome the heaviest exertions through coca, yes, who were possibly rescued from death by starvation through coca, by far exceed the few coqueros who have undermined their health by immoderate use. In the same manner, only a misplaced hypocrisy can condemn the vinous cup of old father Noah, because individual drunkards do not know how to observe limit and moderation.

Arthur Schopenhauer on Ernst von Bibra

The famous philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), was extremely critical of Ernst for his vivisection of animals in Parerga and Paralipomena (quoting Payne's translation).

- Deserving of special mention is the atrocity, perpetrated in Nuremberg by Baron von Bibra and reported by him tanquam re bene gesta to the public with inconceivable naïveté in his Vergleichende Untersuchungen über das Gehirn des Menschen und der Wirbelthiere (Mannheim, 1854, pp. 131 ff.). He deliberately arranged for the death by starvation of two rabbits in order to carry out a useless and superfluous research as to whether the chemical constituents of the brain underwent a change in their proportions through death by starvation! For the benefit of science, n’est-ce-pas? Does it never occur to these gentlemen of scalpel and crucible that they are human beings first and chemists afterwards?

- If Bibra’s cruel act could not be prevented, was it left unpunished? At any rate, anyone who has still as much to learn from books as has that von Bibra, should remember that to extort the final answers on the path of cruelty is to put nature on the rack in order to enrich his knowledge, to extort her secrets which have probably long been known.

The Westmister Review

The Westmister Review. July and October, 1854. New Series Vol. VI. London: John Chapman History, Biography, Voyages and Travels. page 282

In contrast to other Germans, Ernst was found to be a consummate outdoors man.

- He can rough it like a backwoodsman, ride like an Anglo-Indian, and shoot condors on the wing with a single ball. Besides this, he is a cultivated, humorous gentleman, with a considerable knowledge of human things, and an able naturalist as well, knowing how to look about him wherever he is, and capable of making scientifically useful observations.

Historian Ferdinand Gregorovius

Ferdinand Gregorovius described vividly his visit to the eccentric Ernst published in 1893.[2]

- To-day von Kreling took me to call on a wonderful old gentleman, Baron von Bibra, whose house, furnished in old Frankish style, he wished me to see. The owner bought it several years ago, and has arranged within it a collection of specimens of old Nuremberg wares : dark, airless rooms are crowded with a thousand Frankish things—glass, majolica, arms, books piled in heaps. A Faust-like atmosphere pervades the whole; out of doors rain and hanging plants, that swaying, darkened the windows. Could not join in Kreling's admiration of these superfluous and fantastic objects. The Freiherr has traveled a great deal in America, and has carefully arranged a collection of vessels, skulls, and implements belonging to the wild Indians. In the musty workroom, filled to overflowing with archaic household furniture, stand innumerable glasses, retorts, instruments, flasks, and a furnace, and here he makes analytical experiments in the morning. At four in the afternoon he sits down and writes—novels! An entire compartment in his dusty library stands filled with elegantly bound books, upwards of sixty little volumes, mainly novels, which he wrote between 1861 and 1871. This, the most eccentric of all Freiherrn that I have yet seen, goes about in his chaos of a house, a happy mortal, clad in a grey dressing-gown, his neck bare, calm self-possession, the product of self-satisfaction, written on his face. He opened a book in which I was obliged to write my name. Rain prevented me from going to Ratisbon to-day.

Works (Titles in German)

- Chemische Untersuchungen verschiedener Eiterarten: und einiger anderer krankhafter Substanzen.. Berlin, Albert Förstner 1842 (reprinted c. 2003 Elibron Classics)

- Chemische Untersuchungen über die Knochen und Zähne des Menschen und der Wirbeltiere. Schweinfurt, 1844 (reprinted 2003 Elibron Classics)

- Hülfstabellen zur Erkennung zoochemischer Substanzen. Ferdinard Enke,Erlangen, Druck von E. Th. Jacob 1846.

- Untersuchungen über die Krankheiten der Arbeiter in den Phosphorzündholzfabriken. Erlangen 1847

- Die Ergebnisse der Versuche über die Wirkung des Schwefeläthers. Emil Harless, Ernst von Bibra: Erlangen 1847

- Die Wirkung des Schwefeläthers in chemischer und physiologischer Beziehung Emil Harless, Ernst von Bibra, Erlangen, Verlag von Carl Heyder, 1847 Google Books

- Chemische Fragmente über die Leber und die Galle. Braunschweig 1849

- Untersuchung von Seewasser des Stillen Meeres und des Atlantischen Ozeans (Liebig-Woehlers), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmazie, Vol. 77 (1851)

- Die Algodon-Bay in Bolivien. : K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1852 (75-116 p. plates. 37 cm. Series: Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna. Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse. Denkschriften, Bd. 4, 2. Abh.)

- Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte von Chile, Wiener Denkschriften, Mathem.-Naturw. Klasse, 1853, II

- Reisen in Südamerika. 2 Volumes, Bassermann und Mathy, Mannheim 1854 Google Books

- Vergleichende Untersuchungen über das Gehirn des Menschen und der Wirbeltiere. Verlag von Basserman & Mathy, Mannheim 1854

- Die Narkotischen Genussmittel und der Mensch. Nürnberg, Verlag von Wilhelm Schmid, 1855 /reprinted Leipzig, Wiesbaden 1983 / Chapter (14th) on Hashish republished as Haschisch Anno 1855: Das narotische Genußmittel Hanf und der Mensch Werner Pieper's MedienXperimente, Löhrbach (apparently 1996) ISBN 3-930442-07-8 / translated into English Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants Translated by Hedwig Schleiffer, Forward by Martin Haseneier and extensive technical notes by Jonathan Ot, an ethnobiologist- ISBN 0-89281-498-5 Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont 1995

- Der Kaffee und seine Surrogate. Sitzungsberichte der Akademie der Wissenschaften in München 1858, reprinted 2010 Kessinger Publishing ISBN 1-160-43667-3, Limited Google Books

- Ueber den Atakamit, in Abhandlungen der Naturhistorischen Gesellschaft zu Nürnberg, Wilhelm Schmid, Nürnberg 1858 (pp. 221–232) Google Books

- Untersuchung von Seewasser des stillen Meeres und des atlantischen Oceans, in Abhandlungen der Naturhistorischen Gesellschaft zu Nürnberg, Wilhelm Schmid, Nürnberg 1858 (pp. 81 – 91) Google Books

- Die Getreidearten und das Brot. Nürnberg 1860, 2nd Edition 1861 502 pages Google Books

- Erinnerungen aus Süda-Amerika. 3 Volumes, Leipzig 1861 (reprinted 2007 as one volume with modern forward, ISBN 9783865030450) Google Books version of 1861 printing

- Die Schmuggler von Valparaiso. Aus den Südamerikanischen Erinnerungen des Ernst, Freiherrn v. Bibra. unknown date, published pp. 2–20 No. 79 Deutsche Jugendhefte, Druck und Verlag der Buchhandlung Ludwig Auer Pädagogische Stiftung Cassianeum in Donauwörth, c. 1920

- Die Schmugglerhöhle. Aus den Südamerikanischen Erinnerungen des Ersnt, Freiherrn v. Bibra. unknown date, published pp. 20–26 No. 79 Deutsche Jugendhefte, Druck und Verlag der Buchhandlung Ludwig Auer Pädagogische Stiftung Cassianeum in Donauwörth, c. 1920

- Aus Chile, Peru und Brasilien. 3 Volumes, Leipzig 1862 Google Books

- Die Bronzen und Kupferlegierungen der alten und ältesten Völker, mit Rücksichtnahme auf jene der Neuzeit. Verlag von Ferdinand Enke, Erlangen 1869, reprinted 2010.

- Über einen merkwürdigen Blitzschlag, Gaea, vol. 5, 1869.

- Über den Blitz, Gaea, vol. 6, 1870.

- Über alte Eisen- und Silberfunde. Nürnberg, Richter & Kappler 1873 (reprinted 2003 Elibron Classics) limited preview Google Books

- Über die Gewinnung des Silbers aus Cyansilberlösungen, und über die Reduction von Clorsilber. - Barth 1876

Some of his novels include:

- Ein Juwel. Leipzig 1863

- Hoffnungen in Peru, Jena and Leipzig, 1864, 3 volumes vol. 1vol. 2 Google Books

- Reiseskizzen und Novellen. Jena ; Leipzig : Costenoble, 1864, 4 volumes Google Books

- Tzarogy. Jena ; Leipzig : Costenoble, 1865 (3 volumes) Google Books

- Ein edles Frauenherz. 1866, 2nd Ed., Jena 1869 (reprinted 2003, 3 volumes Elibron Classics) Google Books

- Erlebtes und Geträumtes: Novellen und Erzählungen, Jena, 1867, 3 volumes vol. 3 Google Books

- Die Schatzgräber. Multiple volumes Jena : Costenoble, 1867, 3 volumes Google Books

- Aus jungen und alten Tagen : Erinnerungen. Jena : Costenoble, 1868, 3 volumes (may be nonfiction)

- Graf Ellern, Leipzig, 1869 3 volumes Vol. 3 Google Books

- Abenteuer eines jungen Peruaners in Deutschland. Jena 1870, 3 volumes

- Die Kinder des Gauners. Nürnberg 1872

- Hieronimus Scottus : ein Zeitbild aus dem 16. u. 17. Jahrhundert Multiple Volumes. Berlin, 1873

- Wackere Frauen. Jena 1876, three volumes

- Die neun Stationen des Herrn v. Scherenberg. Jena 1880, 2 volumes

Literature

German

- Frühe Erlanger Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der äther- und Chloroformnarkose : Die tierexperimentellen Untersuchungen von Ernst von Bibra und Emil Harless U. v. Hintzenstern, H. Petermann, W. Schwarz Der Anaesthesist Issue Volume 50, Number 11 / November, 2001;

- Rudolf Beissel Ernst Freiherr von Bibra. Ein Naturforscher mit schöngeistigen Neigungen. In: Augustin, Siegfried - Mittelstadt, Axel (Hrsg.): Vom Lederstrumpf zum Winnetou. Munich 1981.

- Rudolf Beissel and Erich Salomon Ernst Freiherr von Bibra In: Schegk, Friedrich (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Reise- und Abenteuerliteratur. Meitingen o.J. (1988 ff.)

- Dr. Sigmund Günther:”Der fränkische Naturforscher Ernst v. Bibra (1806–1878) in seinen Beziehungen zur Erdkunde” Saecular-Feier der Naturhistorischen Gesellschaft in Nürnberg 1801–1901, U. E. Sebald, Nürnberg, c. 1901. 16 pp.

- Knoblauch, H. 1878 [Bibra, E. F. von] Leopoldina 14

- Rüdiger Kutz: Zum Leben des Naturforschers Ernst von Bibra I, Franconiae Würzburg. In: Frankenzeitung, Würzburg, 1999 (118), pp. 56–60.

- Meyers Konversationslexikon von 1888 Band 2 von Atlantis bis Blatthornk, page 895: Basis of much of initial article.

- Wilhelm Frhr. von Bibra, Beiträge zur Familien Geschichte der Reichsfreiherrn von Bibra, Dritter Band (vol. 3), 1888, pages 200–206;

- Martin Stingl, REICHFREIHEIT UND FÜRSTENDIENST DIE DIENSTBEZIEHUNGEN DER BIBRA 1500 BIS 1806, Verlag Degener & Co, 1994, 341 pages, ISBN 3-7686-9131-4;

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga und Paralipomena II/2, Züricher Ausgabe 1977, Kap. 15. Ueber Religion, § 177. Ueber das Christenthum, pp. 412/413.

- Schwinger, Hans Biography Ein Humboldt aus Franken: Dr. Ernst von Bibra: Sein Leben und Wirken in Zeiten der Unruhe und des Wandels, 265 pages

- Werner Schultheiß (1955), "Bibra, Ernst Freiherr von", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 2, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 216–216

- Matthias Witzmann: Eigenes und Fremdes. Hispanoamerika in Bestsellern der deutschen Abenteuer- und Reiseliteratur (1850–1914). Dr. Hut, München 2006. ISBN 3-89963-321-0

- Biography in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Vol. 47, Leipzig 1903, p. 758.

English

- Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants 1995 Translation of Die narkotischen Genussmittel und der Mensch Translated by Hedwig Schleiffer, Forward by Martin Haseneier and extensive technical notes by Jonathan Ot, an ethnobiologist- ISBN 0-89281-498-5

- Parerga and Paralipomena by Arthur Schopenhauer. Translated from the German by E.F.J. Payne, Vol. II, Oxford University Press 1974, XV. On Religion, § 177 On Christianity, p. 374/375.

- Anonym 1878, [Bibra, E. F. von] American Journal of Science and Arts, 3. Ser., New Haven/Conn. 16 : 164

External links

- Ernst Freiherr von Bibra (1806–1878) - Chemiker und Toxikologe - Rolf Giebelmann

- Ernst von Bibra Page on vonBibra.net, images of Ernst von Bibra, digital images of German language section on Ernst von Bibra from family history

References

- ↑ "Barley". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh Edition ed.). Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica. 1910. p. 405. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=NLkNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA414&dq=von+Bibra&lr=&as_brr=1&output=text#c_top