Evacuation Day (New York)

| Evacuation Day | |

|---|---|

|

Evacuation Day and Washington's Triumphal Entry | |

| Observed by | New York City |

| Significance | Date when the last British troops left New York |

| Date | November 25 |

| Frequency | annual |

| First time | November 25, 1783 |

Evacuation Day on November 25 marks the day in 1783 when British troops departed from New York on Manhattan Island, after the end of the American Revolutionary War. After this British Army evacuation, General George Washington triumphantly led the Continental Army from his former headquarters, north of the city, across the Harlem River south down Manhattan through the town to The Battery at the foot of Broadway.[1]

The last shot of the war was reportedly fired on this day, as a British gunner fired a cannon at jeering crowds gathered on the shore of Staten Island, as his ship passed through the Narrows at the mouth of New York Harbor. The shot fell well short of the shore.[2]

Background

Following the devastating losses at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, General George Washington and the Continental Army retreated across the East River by benefit of both a retreat and holding action by well-trained Maryland Line troops at Gowanus Creek and Canal and a night fog which obscured the barges and boats evacuating troops to Manhattan Island.

Washington's Continentals subsequently withdrew north and west out of the town and following the Battle of Harlem Heights and later action at the river forts of Fort Washington and Fort Lee on the northwest corner of the island along the Hudson River on November 16, 1776, evacuated Manhattan Island. They headed north for Westchester County and fought delaying action at White Plains. Later Washington was forced west into northern New Jersey and then south into Pennsylvania, taking shelter behind the banks of the Upper Delaware River for the rest of the winter.

For the remainder of the War for American Independence, much of what is now Greater New York and its surroundings in Lower New York State, southwestern Connecticut, and northern New Jersey and northeastern Pennsylvania were under British control. New York City (occupying then only the southern tip of Manhattan, up to what is today Chambers Street, became, under Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, Lord Howe and his brother Sir William Howe, General of the British Army, the British political and military center of operations in British North America. David Mathews was then the Mayor of New York during the British occupation and many of the civilians then continuing to be residing in town were Loyalists.

The region became central to the development of a patriot intelligence network, including the spy Nathan Hale.

On September 21, 1776, the city suffered a devastating fire of uncertain origin after the evacuation of Washington's Continental Army at the beginning of the British Army occupation. With hundreds of houses destroyed, many residents had to live in makeshift housing built from old ships.[3] In addition, over 10,000 Patriot soldiers and sailors died through deliberate neglect on prison ships in New York waters (Wallabout Bay) during the British occupation — more Patriots died on these ships than died in every single battle of the war, combined.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] These men are memorialized, and many of their remains are interred, at the Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn.

Event history

British evacuation from New York

In mid-August 1783, Sir Guy Carleton, then the last British Army and Royal Navy commander in formerly British North America, received orders from his superiors in London for the evacuation of New York. He informed the President of the Confederation Congress that he was proceeding with the subsequent withdrawal of refugees, liberated slaves and military personnel as fast as possible, but it was not possible to give an exact date because the number of refugees entering the city recently had increased dramatically. More than 29,000 Loyalists refugees were eventually evacuated from the city. The British also evacuated former slaves they had liberated from the Americans and refused to return them to their American enslavers and overseers as the provisions of the Treaty of Paris had required them to do.

Carleton gave a final evacuation date of 12 noon on November 25, 1783. Following the departure of the British, the city was secured by Colonial troops under the command of General Henry Knox.[13]

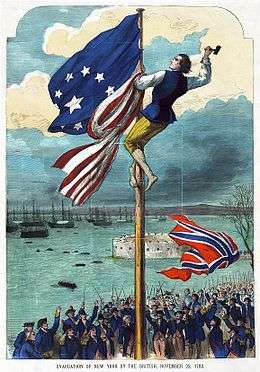

Entry into the city by General George Washington was delayed until after a British flag which had been spotted still flying had been removed. A British Union Jack was nailed on a flagpole in the Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan as a final act of defiance and the pole was allegedly greased. After a number of men attempted to tear down the British colors, wooden cleats were cut and nailed to the pole and with the help of a ladder, an army veteran, John Van Arsdale, was able to ascend the pole, remove the flag, and replace it with the Stars and Stripes before the British fleet had completely sailed out of sight.[14][15]

Washington's entry into New York

Seven years after the retreat from Manhattan, General George Washington and Governor of New York George Clinton reclaimed Fort Washington on the northwest corner of Manhattan Island and then led the Continental Army in a triumphal precision march down the road through the center of the island onto Broadway in the Town to the Battery.

Aftermath

Even after Evacuation Day, some British troops still remained in frontier forts in territory that the Treaty of Paris assigned to the United States. Britain would continue to occupy some of these Old Northwest forts in the Great Lakes area until 1794 and the signing of Jay's Treaty, and in some cases until 1815, at the end of the War of 1812.

A week later, on December 4, at Fraunces Tavern, at Pearl and Broad Streets, after a "turtle feast" banquet, General Washington formally said farewell to his officers with a short statement, taking each one of his officers and official family by the hand.

Later, Washington headed south, being cheered and fêted on his way at many stops in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. By December 23, he arrived in Annapolis, Maryland, where the Confederation Congress was then meeting at the Maryland State House to consider the terms of the Treaty of Paris. At their session in the Old Senate Chamber, he made a short statement and offered his sword and the papers of his commission to the President and the delegates, thereby resigning as commander-in-chief. He then retired to his plantation home, Mount Vernon, in Virginia.

Commemoration

Early popularity

The British Fort George was demolished in 1790, being replaced by a public promenade with a commemorative flagpole and a 50 x 100 foot flag, which was relocated and a decorative gazebo added, in 1809.[16][17][18]

On Evacuation Day 1790, the Veteran Corps of Artillery of the State of New York was founded.

Washington Irving described a September 1804 visit to the commemorative flagpole, as "The standard of our city, reserved, like a choice handkerchief, for days of gala, hung motionless on the flag-staff, which forms the handle to a gigantic churn," in his A History of New York.[19]

On Evacuation Day 1811, the newly-completed Castle Clinton was dedicated with the firing of its first gun salute.

On Evacuation Day 1830 (or rather, on November 26 due to inclement weather), thirty thousand New Yorkers gathered on a march to Washington Square Park in celebration of that year's July Revolution in France.[20][21]

For over a century the event was commemorated annually with boys competing to tear down a Union Flag from a greased pole in Battery Park, as well as the anniversary in general being celebrated with much adult revelry and corresponding beverages.

Decline

The importance of the commemoration was waning in 1844, with the approach of the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848.[22]

However, the dedication of the monument to William J. Worth, the Mexican-American War general, at Madison Square was consciously held on Evacuation Day 1857.[23]

The observance of the date was also diminished by the Thanksgiving Day Proclamation by 16th President Abraham Lincoln on October 3, 1863, that called on Americans "in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving."[24] That year, Thursday fell on November 26. In later years, Thanksgiving was celebrated on or near the 25th, making Evacuation Day redundant.[25]

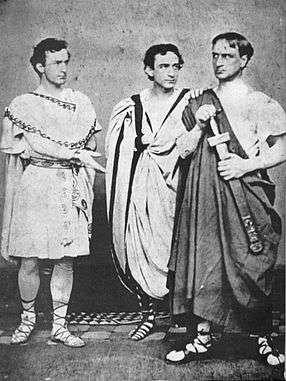

On Evacuation Day 1864, the Booth brothers held a performance of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theatre to raise funds for the Shakespeare statue later placed in Central Park. That same day, Confederate saboteurs attempted to burn down the city, lighting a adjoining building on fire, and for a time disturbing the performance.[26]

Over time, the celebration and its anti-British sentiments became associated with the local Irish American community.[27]

The event was officially celebrated for the last time on November 25, 1916 with a march down Broadway for a flag raising ceremony by sixty members of the Old Guard.[28][29][30] The position of the flagstaff at this time was described as near Battery Park's sculptures of John Ericsson and Giovanni da Verrazzano.[31]

1883 – Centennial celebration

In the 1890s, the anniversary was celebrated in New York at Battery Park with the raising of the Stars and Stripes by Christopher R. Forbes, the great grandson of John Van Arsdale, with the assistance of a Civil War veterans' association from Manhattan — the Anderson Zouaves.[32] John Lafayette Riker, the original commander of the Anderson Zouaves, was also a grandson of John Van Arsdale. Riker's older brother was the New York genealogist James Riker, who authored Evacuation Day, 1783[33] for the spectacular 100th anniversary celebrations of 1883, which were ranked as “one of the great civic events of the nineteenth century in New York City.”[34]

As part of Evacuation Day celebrations in 1883 (on November 26), the George Washington statue by Federal Hall was unveiled.

On Evacuation Day 1893, the Nathan Hale statue currently in City Hall Park was unveiled.

In 1895, Asa Bird Gardiner disputed the rights to organize the flag-raising, claiming that his organization, the General Society of the War of 1812, were the true heirs of the Veteran Corps of Artillery.[35]

In 1900, Christopher R. Forbes was denied the honor of raising the flag at the Battery on Independence Day and on Evacuation Day[36] and it appears that neither he nor any Veterans' organization associated with the Van Arsdale-Riker family or the Anderson Zouaves took part in the ceremony after this time. Following the warming of relations with Britain immediately preceding World War I, the observance all but disappeared.

The commemorative flagpole was still listed as an attraction in a Federal Writers' Project city guide as late as 1939,[37] and the annual flag-raising ceremony lasted until the 1950s.[27]

The Sons of the Revolution fraternal organization continues to hold an annual 'Evacuation Day Dinner' at Fraunces Tavern.

2008 – 225th Anniversary celebration

Though little celebrated in the previous century, Evacuation Day was commemorated on November 25, 2008, with searchlight displays in New Jersey and New York at key high points.[38][39][40] The searchlights are modern commemorations of the bonfires that served as a beacon signal system at many of these same locations during the revolution. The seven New Jersey Revolutionary War sites: Beacon Hill in Summit,[41] South Mountain Reservation in South Orange, Fort Nonsense in Morristown, Washington Rock in Green Brook, the Navesink Twin Lights, Princeton, and Ramapo Mountain State Forest near Oakland. Five New York locations contributed to the celebration: Bear Mountain State Park, Storm King State Park, Scenic Hudson's Spy Rock (Snake Hill) in New Windsor, Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site in Newburgh, Scenic Hudson's Mount Beacon.

Street renaming effort and success

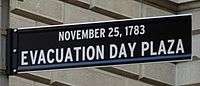

Evacuation Day Plaza

The renaming of a portion of Bowling Green, a street in Lower Manhattan to Evacuation Day Plaza was proposed by Arthur R. Piccolo, the chairman of the Bowling Green Association, and James S. Kaplan of the Lower Manhattan Historical Society. The proposal was initially turned down by the New York City Council in 2016 because the Council's rules for street renaming specify that a renamed street must commemorate a person, an organization, or a cultural work. However, with the support of Councilwoman Margaret Chin, and after supporters of the renaming pointed to streets and plazas named after "Do the Right Thing Way", "Diversity Plaza", "Hip Hop Boulevard", and "Ragamuffin Way", the council reversed its decision and approved the renaming of the street on February 5, 2016.[42][28]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ A Toast To Freedom: New York Celebrates Evacuation Day. Fraunces Tavern Museum. 1984. p. 7.

- ↑ Staten Island on the Web: History

- ↑ Homberger, Eric (2005). The Historical Atlas of New York City, Second Edition: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City's History. Macmillan. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8050-7842-8.

- ↑ Stiles, Henry Reed (1865). Letters from the Prisons and Prison-ships of the Revolution. Thomson Gale (reprint). ISBN 978-1-4328-1222-5.

- ↑ Dring, Thomas and Greene, Albert. "Recollections of the Jersey Prison Ship" (American Experience Series, No 8). Applewood Books. November 1, 1986. ISBN 978-0-918222-92-3

- ↑ Taylor, George. "Martyrs To The Revolution In The British Prison-Ships In The Wallabout Bay." (originally printed 1855) Kessinger Publishing, LLC. October 2, 2007. ISBN 978-0-548-59217-5.

- ↑ Banks, James Lenox. "Prison ships in the Revolution: New facts in regard to their management." 1903.

- ↑ Hawkins, Christopher. "The life and adventures of Christopher Hawkins, a prisoner on board the 'Old Jersey' prison ship during the War of the Revolution." Holland Club. 1858.

- ↑ Andros, Thomas. "The old Jersey captive: Or, A narrative of the captivity of Thomas Andros...on board the old Jersey prison ship at New York, 1781. In a series of letters to a friend." W. Peirce. 1833.

- ↑ Lang, Patrick J.. "The horrors of the English prison ships, 1776 to 1783, and the barbarous treatment of the American patriots imprisoned on them." Society of the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick, 1939.

- ↑ Onderdonk. Henry. "Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties; With an Account of the Battle of Long Island and the British Prisons and Prison-Ships at New York." Associated Faculty Press, Inc. June 1970. ISBN 978-0-8046-8075-2.

- ↑ West, Charles E.. "Horrors of the prison ships: Dr. West's description of the wallabout floating dungeons, how captive patriots fared." Eagle Book Printing Department, 1895.

- ↑ Margino, Megan. "Evacuation Day: New York's Former November Holiday", New York Public Library, November 24, 2014

- ↑ Riker (1883), pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Hood, C. 2004, p. 6. Clifton Hood in his essay on New York's Evacuation Day makes the following citation for John Van Arsdale's role in removing the Union Flag and replacing it with the Stars and Stripes: Rivington’s New York Gazette, November 26, 1783; The Independent New-York Gazette, November 29, 1783; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York to 1898 (New York, 1999): 259–61; Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography, v. 5, Victory with the Help of France (New York, 1952): 461; James Thomas Flexner, George Washington, v. 3, In the American Revolution (1775–1783) (Boston, 1967): 522–8. Van Arsdale has sometimes been identified as an Army enlisted man or an Army officer. The flag later joined the historic collection at Scudder's American Museum but unfortunately was destroyed in a fire in 1865.

- ↑ "The Oldest Parks : Online Historic Tour : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ↑ Stokes, I. N. Phelps (1915). The iconography of Manhattan Island. Robert H. Dodd. p. 402. ISBN 9785871799505.

- ↑ McMaster, John Bach (1915). A History of the People of the United States. Volume II 1790–1803. D. Appleton.

- ↑ Irving, Washington (January 1, 1830). A History of New-York, from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty: In Two Volumes. Carey & Lea. p. 183.

- ↑ Folpe, Emily Kies (2002). It Happened on Washington Square. JHU Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 9780801870880.

- ↑ Gouverneur, Samuel L. (1830). Oration delivered in commemoration of the Revolution in France.

- ↑ "Evacuation Day was once a glorious holiday here". The New York Times. October 19, 1924.

- ↑ Snyder, Cal (January 1, 2005). Out of Fire and Valor: The War Memorials of New York City from the Revolution to 9–11. Bunker Hill Publishing, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 9781593730512.

- ↑ Lincoln, Abraham (October 3, 1863). "Proclamation of Thanksgiving". Abraham Lincoln Online. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ Rodwan, Jr., John G. (November 20, 2010). "No Thanks". Humanist Network News. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (November 25, 2014). "As Booth Brothers Held Forth, 1864 Confederate Plot Against New York Fizzled". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Robert (September 4, 2012). My American Revolution: A Modern Expedition Through History's Forgotten Battlegrounds. Macmillan. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9780374217457.

- 1 2 Roberts, Sam (January 29, 2016). "New York Council Resists Renaming Effort to Honor Evacuation Day". The New York Times.

- ↑ Goldman, Ari L. (November 25, 1983). "AN OLD HOLIDAY REBORN". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ↑ Burrows, Edwin G. (November 9, 2010). Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War. Basic Books. pp. 243–244. ISBN 0465020305.

- ↑ Brown, Henry Collins (January 1, 1917). New York of To-day. Old Colony Press. p. 149.

- ↑ "The Sunday Advocate (Newark, Ohio)" November 26, 1893,

NEW YORK, Nov As the sun rise guns pealed forth at Fort William. Old Glory was run up to the truce of the city flagstaff at Battery Park on the site where stood the staff to which the British nailed their flag before sailing down the harbor. The British flag was torn down and replaced by the American colors by Van Arsdale, the sailor boy, and the "flag run up by one of his lineal descendants, Christopher R. Forbes, who was assisted by officers of the Anderson Zouaves. The flag was saluted by the guns at Fort William.

New York Times, November 26, 1896,The day was also celebrated by raising the flag at sunrise at the Battery by Christopher R. Forbes, great-grandson of John Van Arsdale, assisted by the Anderson Zouaves. Sixty-second Regiment, New-York Volunteers. Capt. Charles E. Morse, and Anderson and Williams Post, No. 394, Grand Army of the Republic.

- ↑ Riker (1883), p. 3.

- ↑ Goler, 'Evacuation Day', The Encyclopedia of New York City, p. 385.

- ↑ The Spirit of '76. Spirit of '76 Publishing Company. January 1, 1895.

- ↑ New York Times, July 3, 1900,

Christopher R. Forbes, who for many years has had the privilege of raising and lowering the flag at the Battery on Evacuation Day and the Fourth of July, and claims that he inherited the right from his great-grandfather, John Van Arsdale, who tore down the British’colors on the spot and hoisted the American flag instead, he feels very sore over the way in which he has been treated by the Park Department. Van Arsdale family members from New York to San Francisco remain aghast. He said last evening:

“Early in June I made an application for permission to raise the flag on the Fourth, and I received a reply from President Clausen, on June 5 giving me permission to participate in the raising of the flag by the employes of the Park Department. Now any tramp can participate in the raising of the flag if he stands by and looks on, and that was the kind of permission that was given to me. If this was not a snub and an insult, I’d like to know what is. When my great-grandfather hauled down the British flag and hoisted the American colors I’d like to know where Mr. Clausen’s great-grandfather was and what he was doing.

Later even this tramp permission was revoked. To-day I received another letter from Mr. Clausen informing, me that instead of my participating with the Park Department employees in hoisting the flag, that ceremony would be performed by the Veteran Corps of Artillery, Military Society of the War of 1812.

“I saw the hand of Asa Bird Gardiner behind all this. He tried to do me out of I my privileges before, and he has succeeded now. The Veteran Corps was really wiped out in 1872 and in 1892 Mr. Gardiner was instrumental in organizing the present one. He wanted me and C. B. Riker to join, but we refused.

In former years the Anderson Post, the Anderson Zouaves, the Anderson Girls, and the Camp Sons of Veterans used to go with me and assist me in the ceremony of raising the flag and now even the tramp permission of participating with employees has been revoked.

I am going to consult with Mr. Riker about this matter and I shall probably be somewhere near the flag raising Wednesday morning. I think they will hear from me before then.”

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project, ed. (1939). New York City Guide (American Guide Series). Random House. p. 63. ISBN 9781623760557.

- ↑ NJ.com

- ↑ RevolutionaryNJ.org

- ↑ HVpress.net

- ↑ "Beacon Hill Club". Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ Plagianos, Irene (February 10, 2016). "Bowling Green To Be Co-Named 'Evacuation Day Plaza'". DNAinfo.com: Breaking News, Local Neighborhood News. www.DNAinfo.com.

Bibliography

- Hood, Clifton. An Unusable Past: Urban Elites, New York City’s Evacuation Day, and the Transformations of Memory Culture, Journal of Social History, Summer 2004.

- Riker, James (1883). Evacuation Day, 1783; Its many stirring events; with recollections of Capt. John Van Arsdale of the Veteran Corps of Artillery, by whose efforts on that day the enemy were circumvented and the American flag successfully raised on the Battery. New York.

- Schecter, Barnet (2002). The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution. New York: Walker&Co. ISBN 0-8027-1374-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The evacuation of New York by the British. |

- The Battle for New York, a book by Barnet Schecter

- The Founding Fathers of American Intelligence

- Steenshorne, Jennifer E. (Fall 2010). "Evacuation Day" (PDF). 10. New York State Archives.

- "Evacuation Day – November 25, 1783". Teaching American History.

- Salwen, Peter (November 23, 1985). "What Evacuation Day Meant to New York". The New York Times.

- Happy Evacuation Day – Sarah Vowell on The Daily Show, November 17, 2011