Fluxional molecule

Fluxional molecules are molecules that undergo dynamics such that some or all of their atoms interchange between symmetry-equivalent positions. Because virtually all molecules are fluxional in some respects, e.g. bond rotations in most organic compounds, the term fluxional depends on the context and the method used to assess the dynamics. Often, a molecule is considered fluxional if its spectroscopic signature exhibits line-broadening (beyond that dictated by the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle) due to chemical exchange. In some cases, where the rates are slow, fluxionality is not detected spectroscopically, but by isotopic labeling.

Carbonium ion

The prototypical fluxional molecule is the carbonium ion, which is protonated methane, CH5+.[1][2][3] In this unusual species, whose IR spectrum was recently experimentally observed[4][5] and more recently understood,[6] the barriers to proton exchange are lower than the zero point energy. Thus, even at absolute zero there is no rigid molecular structure, the H atoms are always in motion. More precisely, the spatial distribution of protons in CH5+ is many times broader than its parent molecule CH4, methane.[7][8]

NMR spectroscopy

Temperature dependent changes in the NMR spectra result from dynamics associated with the fluxional molecules when those dynamics proceed at rates comparable to the frequency differences observed by NMR. The experiment is called DNMR and typically involves recording spectra at various temperatures. In the ideal case, low temperature spectra can be assigned to the "slow exchange limit", whereas spectra recorded at higher temperatures correspond to molecules at "fast exchange limit". Typically, high temperature spectra are simpler than those recorded at low temperatures, since at high temperatures, equivalent sites are averaged out. Prior to the advent of DNMR, kinetics of reactions were measured on nonequilibrium mixtures, monitoring the approach to equilibrium.

Many molecular processes exhibit fluxionality that can be probed on the NMR time scale. Beyond the examples highlighted below, other classic examples include the Cope rearrangement in bullvalene and the chair inversion in cyclohexane.

For processes that are too slow for traditional DNMR analysis, the technique spin saturation transfer (SST) is applicable. This magnetization transfer technique provides rate information, provided that the rates exceed 1/T1.[9]

Dimethylformamide

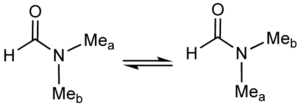

A classic example of a fluxional molecule is dimethylformamide.[10]

At temperatures near 100 °C, the 500 MHz NMR spectrum of this compound shows only one signal for the methyl groups. Near room temperature however, separate signals are seen for the non-equivalent methyl groups. The rate of exchange can be readily calculated at the temperature where the two signals are just merged. This "coalescence temperature" depends on the measuring field. The relevant equation is:

where Δνo is the difference in Hz between the frequencies of the exchanging sites. These frequencies are obtained from the limiting low-temperature NMR spectrum. At these lower temperatures, the dynamics continue, of course, but the contribution of the dynamics to line broadening is negligible.

For example, if Δνo = 1ppm @ 500 MHz

- (ca. 0.5 millisecond half-life)

Ring whizzing in organometallic chemistry

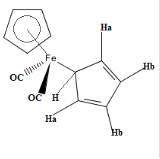

Many organometallic compounds exhibit fluxionality.[11] The compound Fe(η5-C5H5) (η1- C5H5)(CO)2 exhibits the phenomenon of "ring whizzing".

At 30 °C, the 1H NMR spectrum shows only two peaks, one typical (δ5.6) of the η5-C5H5 and the other assigned η1-C5H5. The singlet assigned to the η1-C5H5 ligand splits at low temperatures owing to the slow hopping of the Fe center from carbon to carbon in the η1-C5H5 ligand.[12] Two mechanisms have been proposed, with the consensus favoring the 1,2 shift pathway.[13]

Berry pseudorotation

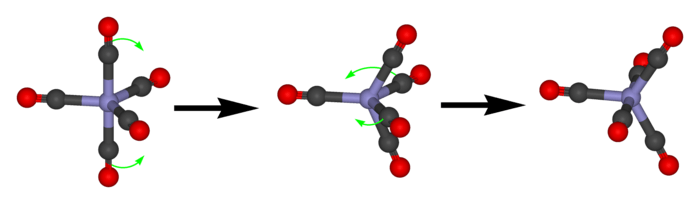

Pentacoordinate molecules of trigonal pyramidal geometry typically exhibit a particular kind of low energy fluxional behavior called Berry pseudorotation. Famous examples of such molecules are iron pentacarbonyl (Fe(CO)5) and phosphorus pentafluoride (PF5). At higher temperatures, only one signal is observed for the ligands (e.g., by 13C or 19F NMR) whereas at low temperatures, two signals in a 2:3 ratio can be resolved. Molecules that are not strictly pentacoordinate are also subject to this process, such as SF4.

IR spectroscopy

Although less common, some dynamics are also observable on the time-scale of IR spectroscopy. One example is electron transfer in a mixed valence dimer of metal clusters. Application of above equation for coalescence of two signals separated by 10 cm−1 gives the following result:[14]

Clearly, processes that induce line-broadening on the IR time-scale must be extremely rapid.

See also

- Molecular symmetry#Nonrigid molecules

- Hapticity#Hapticity and fluxionality

- Pseudorotation

- Bailar twist

- Bartell mechanism

- Berry mechanism

- Ray-Dutt twist

References

- ↑ Kramer, G. M. (1999). Science. 286 (5442): 1051. doi:10.1126/science.286.5442.1051a. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Oka, T.; White, E. T. (1999). Science. 286 (5442): 1051. doi:10.1126/science.286.5442.1051a. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Marx, D.; Parrinello, M. (1999). Science. 286 (5442): 1051. doi:10.1126/science.286.5442.1051a. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ D. W. Boo; Z. F. Liu; A. G. Suits; J. S. Tse; Y. T. Lee (1995). "Dynamics of Carbonium Ions Solvated by Molecular Hydrogen: CH5+(H2)n (n = 1, 2, 3)". Science. 269 (5220): 57–9. Bibcode:1995Sci...269...57B. doi:10.1126/science.269.5220.57. PMID 17787703.

- ↑ E. T. White; J. Tang; T. Oka (1999). "CH5+: The infrared spectrum observed". Science. 284 (5411): 135–7. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..135W. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.135. PMID 10102811.

- ↑ Asvany, O.; Kumar P, P.; Redlich, B.; Hegemann, I.; Schlemmer, S.; Marx, D. (2005). "Understanding the Infrared Spectrum of Bare CH5+". Science. 309 (5738): 1219–1222. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1219A. doi:10.1126/science.1113729. PMID 15994376.

- ↑ Thompson, KC; Crittenden, DL; Jordan, MJ (2005). "CH5+: Chemistry's chameleon unmasked". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (13): 4954–4958. doi:10.1021/ja0482280. PMID 15796561.

- ↑ For an animation of the dynamics of CH5+, see http://www.theochem.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/research/marx/topic4b.en.html

- ↑ Jarek, R. L., Flesher, R. J., Shin, S. K., "Kinetics of Internal Rotation of N,N-Dimethylacetamide: A Spin-Saturation Transfer Experiment", Journal of Chemical Education 1997, volume 74, page 978. doi:10.1021/ed074p978.

- ↑ H. S. Gutowsky; C. H. Holm (1956). "Rate Processes and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra. II. Hindered Internal Rotation of Amides". J. Chem. Phys. 25 (6): 1228–1234. Bibcode:1956JChPh..25.1228G. doi:10.1063/1.1743184.

- ↑ John W. Faller "Stereochemical Nonrigidity of Organometallic Complexes" Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry 2011, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc0211

- ↑ Bennett, Jr. M. J.; Cotton, F. A.; Davison, A.; Faller, J. W.; Lippard, S. J.; Morehouse, S. M. "Stereochemically Nonrigid Organometallic Compounds. I. π-Cyclopentadienyliron Dicarbonyl σ-Cyclopentadiene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966 (88): 4371. doi:10.1021/ja00971a012.

- ↑ Robert B. Jordan, Reaction Mechanisms of Inorganic and Organometallic Systems (Topics in Inorganic Chemistry), 2007. ISBN 978-0195301007

- ↑ Casey H. Londergan; Clifford P. Kubiak (2003). "Electron Transfer and Dynamic Infrared-Band Coalescence: It Looks Like Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy, but a Billion Times Faster". Chemistry: A European Journal. 9 (24): 5969ff. doi:10.1002/chem.200305028.