Foundling Hospital

The Foundling Hospital in London, England was founded in 1739 by the philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram. It was a children's home established for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children." The word "hospital" was used in a more general sense than it is today, simply indicating the institution's "hospitality" to those less fortunate. Nevertheless, one of the top priorities of the committee at the Foundling Hospital was children's health, as they combated smallpox, fevers, consumption, dysentery, and even infections from everyday activities like teething that drove up mortality rates and risked epidemics.[1] With their energies focused on maintaining a disinfected environment, providing simple clothing and fare, the committee paid less attention to and spent less on developing children's education. As a result, financial problems would hound the institution for years to come, despite the growing "fashionableness" of charities like the hospital.[2]

Early history

The Royal Founding Charter, presented by Coram at a distinguished gathering at 'Old' Somerset House to the Duke of Bedford in 1739,[3] contains the aims and rules of the Hospital and the long list of founding Governors and Guardians: this includes 17 dukes, 29 earls, 6 viscounts, 20 barons, 20 baronets, 7 Privy Councillors, the Lord Mayor and 8 aldermen of the City of London; and many more besides.[4]

The first children were admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 25 March 1741, into a temporary house located in Hatton Garden. At first, no questions were asked about child or parent, but a distinguishing token was put on each child by the parent. These were often marked coins, trinkets, pieces of cotton or ribbon, verses written on scraps of paper. Clothes, if any, were carefully recorded. One entry in the record reads, "Paper on the breast, clout on the head." The applications became too numerous, and a system of balloting with red, white and black balls was adopted. Children were seldom taken after they were twelve months old.

On reception, children were sent to wet nurses in the countryside, where they stayed until they were about four or five years old. At sixteen girls were generally apprenticed as servants for four years; at fourteen, boys were apprenticed into variety of occupations, typically for seven years. There was a small benevolent fund for adults.

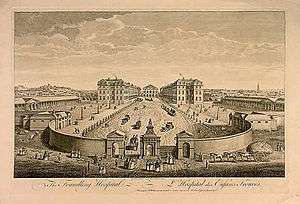

In September 1742, the stone of the new Hospital was laid in the area known as Bloomsbury, lying north of Great Ormond Street and west of Gray's Inn Lane. The Hospital was designed by Theodore Jacobsen as a plain brick building with two wings and a chapel, built around an open courtyard. The western wing was finished in October 1745. An eastern wing was added in 1752 "in order that the girls might be kept separate from the boys". The new Hospital was described as "the most imposing single monument erected by eighteenth century benevolence" and became London's most popular charity.

In 1756, the House of Commons resolved that all children offered should be received, that local receiving places should be appointed all over the country, and that the funds should be publicly guaranteed. A basket was accordingly hung outside the hospital; the maximum age for admission was raised from two months to twelve, and a flood of children poured in from country workhouses. In less than four years 14,934 children were presented, and a vile trade grew up among vagrants, who sometimes became known as "Coram Men", of promising to carry children from the country to the hospital, an undertaking which they often did not perform or performed with great cruelty. Of these 15,000, only 4,400 survived to be apprenticed out. The total expense was about £500,000, which alarmed the House of Commons. After throwing out a bill which proposed to raise the necessary funds by fees from a general system of parochial registration, they came to the conclusion that the indiscriminate admission should be discontinued. The hospital, being thus thrown on its own resources, adopted a system of receiving children only with considerable sums (e.g., £100), which sometimes led to the children being reclaimed by the parent. This practice was finally stopped in 1801; and it henceforth became a fundamental rule that no money was to be received. The committee of inquiry had to be satisfied of the previous good character and present necessity of the mother, and that the father of the child had deserted both mother and child, and that the reception of the child would probably replace the mother in the course of virtue and in the way of an honest livelihood. At that time, illegitimacy carried deep stigma, especially for the mother but also for the child. All the children at the Foundling Hospital were those of unmarried women, and they were all first children of their mothers. The principle was in fact that laid down by Henry Fielding in The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling: "Too true I am afraid it is that many women have become abandoned and have sunk to the last degree of vice [i.e. prostitution] by being unable to retrieve the first slip."

There were some unfortunate incidents, such as the case of Elizabeth Brownrigg (1720–1767), a severely abusive Fetter Lane midwife who mercilessly whipped and otherwise maltreated her adolescent female apprentice domestic servants, leading to the death of one, Mary Clifford, from her injuries, neglect and infected wounds. After the Foundling Hospital authorities investigated, Brownrigg was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang at Tyburn. Thereafter, the Foundling Hospital instituted more thorough investigation of its prospective apprentice masters and mistresses.

Music and art

Music

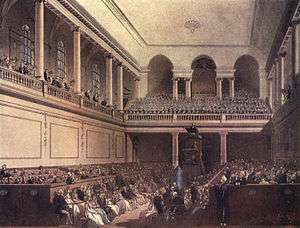

The musical service, which was originally sung by the blind children only, was made fashionable by the generosity of George Frideric Handel, who frequently had Messiah performed there, and who bequeathed to the hospital a fair copy (full score) of his greatest oratorio. Handel's involvement had begun on 1 May 1750 when he directed a performance of Messiah to mark the presentation of the organ (built by Henry Bevington) to the chapel. That first performance was a great success and Handel was elected a Governor of the Hospital on the following day, a position he accepted. In 1774 Dr Charles Burney and a Signor Giardini made an unsuccessful attempt to form in connection with the hospital a public music school, in imitation of the Pio Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, Italy. In 1847, however, a successful juvenile band was started. The educational effects of music were found excellent, and the hospital supplied many musicians to the best army and navy bands.

Art

There was an early connection between the hospital and eminent painters of the reign of George II. Exhibitions of pictures at the Foundling Hospital, which were organized by the Dilettante Society, led to the formation of the Royal Academy in 1768.

William Hogarth, who was childless, had a long association with the Hospital and was a founding Governor. He designed the children's uniforms and the coat of arms, and he and his wife Jane fostered foundling children. Hogarth also decided to set up a permanent art exhibition in the new buildings, encouraging other artists to produce work for the hospital. Indeed, several contemporary English artists decorated the walls of the hospital with their works, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Richard Wilson and Francis Hayman. William Hallett, cabinet maker to nobility, produced all the wood paneling with ornate carving, for the court room.

Hogarth painted a portrait of Thomas Coram for the hospital. He also donated his "Moses Brought Before Pharaoh's Daughter". His painting "March of the Guards to Finchley" was also obtained by the hospital after Hogarth donated lottery tickets for a sale of his works, and the hospital won it. Another noteworthy piece is Roubiliac's bust of Handel. The chapel's altar-piece was originally "Adoration of the Magi" by Casali, but deemed to look too Catholic by the Hospital's Anglican governors, it was replaced by Benjamin West's picture of Christ presenting a little child. The hospital also owns several paintings illustrating life in the institution by Emma Brownlow, daughter of the hospital's administrator. The Foundling Hospital art collection can today be seen at the Foundling Museum.

Relocation

In the 1920s, the Hospital decided to move to a healthier location in the countryside. A proposal to turn the buildings over for university use fell through, and they were eventually sold to a property developer called James White in 1926. He hoped to transfer Covent Garden Market to the site, but the local residents successfully opposed that plan. In the end, the original Hospital building was demolished. The children were moved to Redhill, Surrey, where an old convent was used to lodge them, and then in 1935 to the new purpose-built Foundling Hospital in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. When, in the 1950s, British law moved away from institutionalisation of children toward more family-oriented solutions, such as adoption and foster care, the Foundling Hospital ceased most of its operations. The Berkhamsted buildings were sold to Hertfordshire County Council for use as a school (Ashlyns School)[5] and the Foundling Hospital changed its name to the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children and currently uses the working name Coram.

Today

The Foundling Hospital still has a legacy on the original site. Seven acres (28,000 m²) of it were purchased for use as a playground for children with financial support from the newspaper proprietor Lord Rothermere. This area is now called Coram's Fields and owned by an independent charity, Coram's Fields and the Harmsworth Memorial Playground.[6] The Foundling Hospital itself bought back 2.5 acres (10,000 m²) of land in 1937 and built a new headquarters and a children's centre on the site. Although smaller, the building is in a similar style to the original Foundling Hospital and important aspects of the interior architecture were recreated there. It now houses the Foundling Museum, an independent charity, where the art collection can be seen.[7] The original charity still exists as Coram, registered under the name Thomas Coram Foundation for Children,[8] and is one of London's largest children's charities, operating in adjacent buildings constructed in the 1950s.

In fiction

In the 1840s Charles Dickens lived in Doughty Street, near the Foundling Hospital, and rented a pew in the chapel. The foundlings inspired characters in his novels including the apprentice Tattycoram in Little Dorrit, and Walter Wilding the foundling in No Thoroughfare. In "Received a Blank Child", published in Household Words in March 1853, Dickens writes about two foundlings, numbers 20,563 and 20,564, the title referring to the words "received a [blank] child" on the form filled out when a foundling was accepted at the Hospital.[9]

The Foundling Hospital is the setting for Jamila Gavin's 2000 novel Coram Boy. The story recounts elements of the problems mentioned above, when "Coram Men" were preying on people desperate for their children.

It also appears in three books by Jacqueline Wilson: Hetty Feather, Sapphire Battersea and Emerald Star. In the first story, Hetty Feather, Hetty has just arrived in the Hospital, after her time with her foster family. This book tells us about her new life in the Foundling Hospital. In Sapphire Battersea, Hetty has just left the Hospital and speaks ill of it. The Foundling Hospital is mentioned in Emerald Star, although it is mainly about Hetty growing up.

In addition, it serves as the setting for Liana LeFey's historical romance novel To Ruin a Rake.

See also

- Blackguard Children

- Child abandonment

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

- List of organisations with a British royal charter

- Thomas Coram Foundation for Children

- Taylor White, a founding governor of the Foundling Hospital and its first Treasurer

References

- ↑ McCLure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 205–210.

- ↑ McClure, Ruth K. (1981). Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 219.

- ↑ Godfrey, Walter H.; Marcham, W. McB. (eds.) (1952). 'The Foundling Hospital', in Survey of London: Volume 24, the Parish of St Pancras Part 4: King's Cross Neighbourhood. London: London County Council, pp. 10-24. Accessed 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Copy of the Royal Charter Establishing an Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. London: Printed for J. Osborn, at the Golden-Ball in Paternoster Row. 1739.

- ↑ "Ashlyns School, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire". Ashlyns.herts.sch.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ↑ "Coram's Fields and the Harmsworth Memorial Playground". Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ Charity Commission. The Foundling Museum, registered charity no. 1071167.

- ↑ Charity Commission. Thomas Coram Foundation for Children (formerly Foundling Hospital), registered charity no. 312278.

- ↑ Pugh, G. (2007) London's forgotten children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital. Tempus, Stroud: pp. 81-2.

Bibliography

- Enlightened Self-interest: The Foundling Hospital and Hogarth. exhibition catalogue, Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, London 1997.

- The Foundling Museum Guide Book. The Foundling Museum, London 2004.

- Gavin, Jamila . Coram Boy. London: Egmont/Mammoth, 2000: ISBN 1-4052-1282-9 (U.S. Edition: New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001: ISBN 0-374-31544-2)

- Jocelyn, Marthe . A Home for Foundlings. Toronto: Tundra Books: 2005: ISBN 0-88776-709-5

- McClure, Ruth . Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981: ISBN 0-300-02465-7

- Nichols, R.H. and F A. Wray. The History of the Foundling Hospital. (London: Oxford University Press, 1935).

- Oliver, Christine and Peter Aggleton. Coram's Children: Growing Up in the Care of the Foundling Hospital: 1900-1955. London: Coram Family, 2000: ISBN 0-9536613-1-8

- Zunshine, Lisa. Bastards and Foundlings: Illegitimacy in Eighteenth Century England, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005: ISBN 0-8142-0995-5

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Foundling Hospital. |

- The Foundling Museum

- Old Coram Association

- The Foundling Museum section at the Survey of London online

- BBC British History: The Foundling Hospital