George Sutherland

| George Sutherland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office September 5, 1922 – January 17, 1938[1] | |

| Nominated by | Warren Harding |

| Preceded by | John Clarke |

| Succeeded by | Stanley Reed |

| United States Senator from Utah | |

|

In office March 4, 1905 – March 4, 1917 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Kearns |

| Succeeded by | William King |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Utah's At-large district | |

|

In office March 4, 1901 – March 3, 1903 | |

| Preceded by | William King |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Howell |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Alexander George Sutherland March 25, 1862 Stony Stratford, United Kingdom |

| Died |

July 18, 1942 (aged 80) Stockbridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party |

Liberal Party (1883–1896) Republican (1896–1942) |

| Spouse(s) | Rosamond Lee |

| Children |

Edith Emma Philip |

| Alma mater |

Brigham Young University, Utah University of Michigan, Ann Arbor |

| Religion | Episcopalianism |

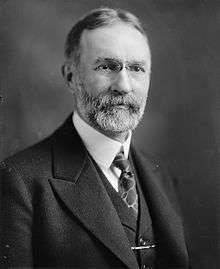

Alexander George Sutherland[2] (March 25, 1862 – July 18, 1942) was an English-born U.S. jurist and politician. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938.

Biography

Early life and career

Sutherland was born in Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire, England, to a Scottish father, Alexander George Sutherland, and an English mother, Frances, née Slater. A recent convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), Alexander Sutherland moved the family to Utah Territory in the summer of 1863. Initially Alexander Sutherland settled his family in Springville, Utah, but moved to Montana and prospected for a few years before moving his family back to Utah Territory in 1869, where he pursued a number of different occupations.[3] In the 1870s the Sutherland family left Mormonism, with George remaining unbaptized.[4]

At the age of twelve, the need to help his family financially forced Sutherland to leave school and take a job, first as a clerk in a clothing store, then as an agent of the Wells Fargo Company. Yet Sutherland aspired to a higher education, and in 1879 had saved enough to attend Brigham Young Academy. There he studied under Karl G. Maeser, who proved an important influence in his intellectual development, most notably by introducing Sutherland to the ideas of Herbert Spencer, which would form an enduring part of Sutherland's philosophy. After graduating in 1881, Sutherland worked for the Rio Grande Western Railroad for a little over a year before moving to Michigan to enroll in the University of Michigan Law School, where he was a student of Thomas M. Cooley.[5] Sutherland left school before earning his law degree.

After admission to the Michigan bar, he married Rosamond Lee in 1883; their marriage proved a happy one, and produced two daughters and a son. After his marriage, Sutherland moved back to Utah Territory, where he joined his father (who had also become a lawyer) in a partnership in Provo. In 1886, they dissolved their partnership and Sutherland formed a new one with Samuel Thurman, a future chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court. After running unsuccessfully as the Liberal Party candidate for mayor of Provo, Sutherland moved to Salt Lake City in 1893. There he joined one of the state's leading law firms, and the following year was one of the organizers of the Utah State Bar Association. In 1896 he was elected as a Republican to the newly created Utah State Senate, where he served as chairman of the senate's Judiciary Committee and sponsored legislation granting powers of eminent domain to mining and irrigation companies.[6]

Years in Congress

In 1900, Sutherland received the Republican nomination as the party's candidate for Utah's seat in the federal House of Representatives. In the subsequent election, Sutherland narrowly defeated the Democratic incumbent (and his former law partner), William H. King, by 241 votes out of over 90,000 cast. He went on to serve as a Representative in the 57th Congress, where he fought to maintain the tariff on sugar and was active in both Indian affairs and legislation addressing the irrigation of arid lands.[7]

Sutherland declined to run for a second term and returned to Utah in order to campaign for election to the United States Senate. With the state legislature firmly under Republican control, the contest was an intra-party battle with the incumbent, Thomas Kearns. With the backing of Utah's other senator, Reed Smoot, Sutherland secured the unanimous support of the caucus in January 1905. Sutherland repaid his debt to Smoot in 1907 by speaking on the floor in the Senate in defense of the senior senator during the climax of the Smoot hearings.[8]

Sutherland's tenure in the Senate coincided with the Progressive Era in American politics. He voted for much of Theodore Roosevelt' s legislative programs, including the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Hepburn Act, and the Federal Employers Liability Act. He was also "a longstanding women’s rights advocate. He introduced the Nineteenth Amendment into the Senate . . . campaigned for the passage of that amendment, helped draft the Equal Rights Amendment, and was a friend and adviser of Alice Paul of the National Woman's Party."[9] Yet he generally sided with the "Old Guard" of conservatives who battled with their Progressive counterparts within the party during William Howard Taft's presidency. He was also involved closely with the legal codification of the period, and joined Taft in opposing the legislation admitting New Mexico and Arizona into the union because of clauses within their constitutions allowing for the recall of judges.[10]

The election of Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic takeover of Congress in 1912 put Sutherland and the other conservatives on the defensive. By now a national figure, Sutherland opposed many of Wilson's legislative proposals and foreign policy measures. Sutherland's opposition contributed to his defeat in 1916, when he faced reelection for the first time under the terms of the Seventeenth Amendment. Once again he faced William H. King, who campaigned on Sutherland's opposition to the president. Following his Senate defeat, he resumed the private practice of law in Washington, D.C., and served as President of the American Bar Association from 1916 to 1917.[11]

Supreme Court

On September 5, 1922, Sutherland was nominated by President Warren G. Harding to the Associate Justice seat on the Supreme Court of the United States vacated by John Hessin Clarke. Sutherland was confirmed by the United States Senate on September 5, 1922, and received his commission the same day.

Sutherland wrote a decision refusing to declare unconstitutional a local zoning ordinance, in Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co.. The decision was widely interpreted as a general endorsement of the constitutionality of zoning laws.

During Franklin Roosevelt's early years in office as president, Justice Sutherland along with James Clark McReynolds, Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter, was part of the conservative "Four Horsemen", who were instrumental in striking down Roosevelt's New Deal legislation. Sutherland was regarded as the leader of this conservative bloc of judges.[12]

Important decisions authored by Sutherland include the 1932 case Powell v. Alabama, overturning a conviction in the Scottsboro Boys Case because the defendant, Ozie Powell, was deprived of his right to counsel, and U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936). In the Curtiss-Wright case, Sutherland wrote the majority decision; giving the president wide powers in conducting foreign affairs. The case later became very influential in widening the executive branch's powers about foreign policy.

In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), Sutherland authored the unanimous decision which decided that Indian Sikhs, although classified as members of the "Caucasian race," were not white within the meaning of the Naturalization Act of 1790, and thus ineligible for naturalized American citizenship.

In 1937, the Supreme Court began to side with New Deal policies and Sutherland's influence declined.[12] Sutherland retired from the U.S. Supreme Court on January 17, 1938, as the balance of power in the US Supreme Court was shifting away from him.[12] Following his retirement as a Justice, Sutherland sat by special designation as a member of the Second Circuit panel that reviewed the bribery conviction of former Second Circuit Chief Judge Martin Manton, and authored the court's opinion upholding the conviction.

Death

While vacationing with his wife at a resort in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Sutherland suffered a severe heart attack on the afternoon of July 17, 1942. He died in his sleep some time between 4:00 AM and 9:30 AM on July 18, his wife by his side. They had celebrated their 59th wedding anniversary just 29 days before.[13]

Sutherland was interred at Abbey Mausoleum in Arlington County, Virginia. In 1958, his remains were removed and reburied at Cedar Hill Cemetery near Suitland, Maryland.[14]

Religion

As an infant, Sutherland had been baptized in the Anglican church,[15] and his religion is often listed as Episcopalian.[16][17][18] Sutherland was never a member of the LDS Church, as his parents left Mormonism in his childhood.[4] However, he maintained loyal friendships with prominent Mormons, and fondly remembered his time at Brigham Young Academy.[19] Sutherland rejected Mormonism, specifically polygamy and "collectivist economic practices," but he had studied the religion at BYU and followed the Mormon practice of alcohol abstinence.[20] Lawyer and commentator Jay Sekulow wrote that some of Sutherland's views had been influenced by Mormonism.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ "Federal Judicial Center: George Sutherland". 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ Carter & Phillips 2008, p. 324

- ↑ Paschal, Joel Francis. Mr. Justice Sutherland: A Man Against the State. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951, p. 3.

- 1 2 Carter & Phillips 2008, p. 325

- ↑ Paschal, p. 5-20.

- ↑ Paschal, p. 20-24, 36; Paul, Ellen Frankel. "Sutherland, George." In The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. 2d ed. Kermit L. Hall, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 991.

- ↑ Paschal, p. 37-46.

- ↑ Paschal, p. 49-52.

- ↑ Bernstein, David (2011-05-09) On a Certain Type of Historical Error, Legal History Blog

- ↑ Paschal, p. 53-73.

- ↑ Paschal, op cit, pgs. 82-105.

- 1 2 3 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/capitalism/robes_sutherland.html

- ↑ "Geo. Sutherland Dies in Berkshires." New York Times. July 19, 1942.

- ↑ Waskey, A.J.L. "Sutherland, George." In The Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court. David Shultz, ed. New York: Facts on File, 2005, p. 450; Atkinson, David N. Leaving the Bench: Supreme Court Justices at the End. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1999, p. 106.

- ↑ Clare Cushman (2012). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012. CQ Press. p. 314. ISBN 1452235341. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ↑ The TIME Almanac 2006. Information Please, LLC. 2005. ISBN 1932994416. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ↑ "Episcopalian Politicians in Utah". The Political Graveyard. December 15, 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ↑ "Famous Anglicans and Episcopalians". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ↑ Carter & Phillips 2008, pp. 328, 333–34, 336–38

- ↑ Carter & Phillips 2008, pp. 333–34, 336

- ↑ Jay Sekulow (2007). Witnessing Their Faith: Religious Influence on Supreme Court Justices and Their Opinions. Sheed and Ward. pp. 179–181. ISBN 146167543X. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

Sources

- Carter, Edward L.; Phillips, James C. (2008), "Mormon Education of a Gentile Justice: George Sutherland and Brigham Young Academy", Journal of Supreme Court History, 33 (3): 326

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Abraham, Henry J. (1999). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Clinton (Revised ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9604-9.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Olken, Samuel R. (March 2009). "Justice Sutherland Reconsidered". Vanderbilt Law Review. 62: 639–93.

- Paschal, Joel Francis (1951). Mr. Justice Sutherland: A Man against the State. Princeton University Press.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George Sutherland |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Sutherland. |

- United States Congress. "George Sutherland (id: S001080)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- George Sutherland at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- "Utah History To Go: Biography of George Sutherland". Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- "Return of George Sutherland, by Hadley Arkes". Retrieved September 24, 2010.

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William King |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Utah's at-large congressional district 1901–1903 |

Succeeded by Joseph Howell |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Thomas Kearns |

Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from Utah (Class 1) 1904, 1910, 1916 |

Succeeded by Ernest Bamberger |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Thomas Kearns |

United States Senator (Class 1) from Utah 1905–1917 Served alongside: Reed Smoot |

Succeeded by William King |

| Preceded by Nathan Scott |

Chairperson of the Senate Environment Committee 1911–1913 |

Succeeded by Claude Swanson |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by John Clarke |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1922–1938 |

Succeeded by Stanley Reed |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||