Great Dayton Flood

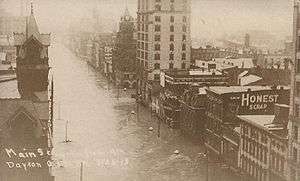

Main Street in Dayton, Ohio during the flood | |

| Date | 21 March 1913–26 March 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | Dayton, Ohio and other cities in the Great Miami River watershed |

| Deaths | est. 360 |

| Property damage | $100,000,000 |

The Great Dayton Flood of 1913 hit Dayton, Ohio, and the surrounding area with water from the Great Miami River, causing the greatest natural disaster in Ohio history. In response, the General Assembly passed the Vonderheide Act to enable the formation of conservancy districts. The Miami Conservancy District, which included Dayton and the surrounding area, became one of the first major flood control districts in Ohio and the United States.[1]

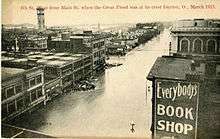

The Dayton flood of March 1913 was caused by a series of winter storms that hit the Midwest in late March. Within three days, 8–11 inches (200–280 mm) of rain fell throughout the Great Miami River watershed on already saturated soil,[2] resulting in more than 90 percent runoff that caused the river and its tributaries to overflow. The existing series of levees failed, and downtown Dayton experienced flooding up to 20 feet (6.1 m) deep. This flood is still the flood of record for the Great Miami River watershed, and the amount of water that passed through the river channel during this storm equals the flow over Niagara Falls each month.[3]

The Great Miami River watershed covers nearly 4,000 square miles (10,000 km2) and 115 miles (185 km) of channel that feeds into the Ohio River.[4] Other Ohio cities experienced flooding from these storms, but none as extensive as the cities of Dayton, Piqua, Troy, and Hamilton along the Great Miami River.[5]

Background conditions

Dayton was founded along the Great Miami River at the convergence of its three tributaries, the Stillwater River, the Mad River, and Wolf Creek. The waterways converge within 1 mile (1.6 km) along the river channel near the city's central business district.[4] When Israel Ludlow laid out Dayton in 1795, the local Native Americans warned him about the recurring flooding. Prior to the 1913 flood, the Dayton area experienced major floods nearly every other decade, with major water flows in 1805, 1828, 1847, 1866, and 1898.[6] Most of downtown Dayton lies in the Great Miami River’s natural flood plain.

The storms that caused the flood at Dayton continued over several days and affected an area across all or parts of more than a dozen states, most notably states in the Midwest and along the Mississippi River.[7][8][9] Heavy rain and snow produced widespread flooding known as the Great Flood of 1913 over Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, New York, and Pennsylvania.[10][11]

Timeline

The following events took place between March 21 and March 26, 1913.[4]

- Friday, March 21, 1913

- The first storm arrives with strong winds and temperatures around 60 °F (16 °C).

- Saturday, March 22, 1913

- The area experiences a sunny day until the second storm arrives, dropping temperatures to the 20s, which causes the ground to briefly freeze on the surface during the morning and thaw by late afternoon.

- Sunday, March 23, 1913 (Easter Sunday)

- The third storm brings rain to the entire Ohio River valley. Saturated soil could not absorb any more water, and nearly all of the rain becomes runoff that flows into the Great Miami River and its tributaries.

- Monday, March 24, 1913

- 7:00 am—After a day and night of heavy rains with precipitation between 8 and 11 inches (200 and 280 mm), the river reaches its high stage for the year at 11.6 feet (3.5 m) and continues to rise.

- Tuesday, March 25, 1913

- Midnight—The Dayton police are warned that the Herman Street levee was weakening and they start the warning sirens and alarms.

- 5:30 am—City engineer Gaylord Cummin reports that water is at the top of the levees and is flowing at 100,000 cubic feet per second (2,800 m3/s), an unprecedented rate.

- 6:00 am—Water overflowing the levees begins to appear in the city streets.

- 8:00 am—Levees on the south side of the downtown business district fail and flooding begins downtown.[12]

- Water levels continue to rise throughout the day.

- Wednesday, March 26, 1913

- 1:30 am—The waters crest, reaching up to 20 feet (6.1 m) in the downtown area.

- Later that morning a gas explosion downtown, near the intersection of 5th Street and Wilkinson, starts a fire that destroys most of a city block. The open gas lines were responsible for several fires throughout the city. The fire department was unable to reach the fires and many additional buildings were lost.[6][13]

Relief efforts

Ohio governor James M. Cox sent the Ohio National Guard to protect property and life and support the city's recovery efforts. The Guard was not able to reach the city for several days because of the high water conditions throughout the state. They built refugee camps using tents for people permanently or temporarily displaced from their homes.[4]

Initial access was provided by the Dayton, Lebanon and Cincinnati Railroad and Terminal Company, the only line not affected by the flood.

Governor Cox called on the state legislature to appropriate $250,000 (about $11 million in today's dollars) for emergency aid and declared a 10-day bank holiday.[14] When President Wilson sent telegrams to the governors of Ohio and Indiana asking how the federal government might help, Cox replied with a request for tents, rations, supplies, and physicians.[15] Governor Cox sent a telegram to the American Red Cross headquarters in Washington D.C. requesting their assistance in Dayton and surrounding communities.[16] Its agents and nurses focused their efforts in 112 of Ohio's hardest-hit communities, which included Dayton, primarily along Ohio's major rivers.[17]

Some of the Dayton flood victims made their way to National Cash Register's factory and headquarters, where John H. Patterson, the company's president, and his factory workers assisted flood victims and relief workers.[14] NCR employees built nearly 300 flat-bottomed rescue boats.[5] Patterson organized rescue teams to save the thousands of people stranded on roofs and the upper stories of buildings.[6] He turned the NCR factory on Stewart Street into an emergency shelter providing food and lodging and organized local doctors and nurses to provide medical care.[5] NCR facilities served as the Dayton headquarters for the American Red Cross and Ohio National Guard relief and rescue efforts and provided food and shelter, a hospital and medical personnel, and a makeshift morgue, while the company's grounds became a temporary campground for the city's homeless. Patterson provided news reporters and photographers with food and lodging and access to equipment and communications to file their stories. When the presses of the Dayton Daily News became inoperable due to the floodwaters, the newspaper used NCR's in-house printing press, providing Dayton and NCR with press coverage on AP and UPI newswires.[14]

Casualties and property damage

As the water receded, damages were assessed in the Dayton area:

- More than 360 people died;[4][18][19]

- Nearly 65,000 people were displaced;[20]

- Approximately 20,000 homes were destroyed;[21]

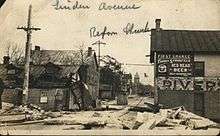

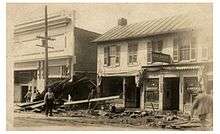

- Buildings were moved off their foundations and debris in the moving water damaged other structures;

- Property damage to homes, businesses, factories, and railroads were over $100 million (in 1913 dollars, more than $2 billion in today's dollars);[3]

- Nearly 1,400 horses and 2,000 other domestic animals died.[4]

Cleanup and rebuilding efforts took approximately one year to repair the flood damage. The economic impacts of the flood took most of a decade to recover.[4] Destruction from the flood is also responsible for the dearth of old and historical buildings in the urban core of Dayton, whose center city resembles newer cities in the western United States.

Flood control

Rather than accept defeat from the flood, the people of the Dayton area were determined to prevent another flood disaster of the same magnitude. Led by Patterson's vision for a managed watershed district, on March 27, 1913, Governor Cox appointed people to the Dayton Citizens Relief Commission. In May, the commission conducted a 10-day fundraiser which collected over $2 million (in 1913 dollars) to fund the flood control effort.[4] The commission hired hydrological engineer Arthur E. Morgan[3] and his Morgan Engineering Company from Tennessee to design an extensive plan that used levees and dams to protect Dayton from future floods.[22] [23] Morgan later worked on flood plain projects in Pueblo, Colorado, and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Morgan hired nearly 50 engineers to analyze the Miami Valley watershed and precipitation patterns and to determine the flood volume. They analyzed European flood data for information about general flooding patterns. Based on this analysis Morgan presented eight different flood control plans to the City of Dayton officials in October 1913. The city selected a plan based on the flood control system in the Loire Valley in France, consisting of five earthen dams and modifications to the river channel through Dayton. The dams would have conduits to release a limited amount of water, and a wider river channel would use larger levees supported by a series of training levees. Flood storage areas behind the dams would be used as farmland between floods. Morgan's goal was to develop a flood plan that would handle 140 percent of the water from the 1913 flood.[4] The analysis had determined the river channel boundaries for the expected 1,000-year major floods and all business located in that area would be relocated.

With the support of Governor Cox, Dayton attorney John McMahon worked on drafting the Vonderheide Act, Ohio's conservancy law, in 1914.[5] The Act allowed local governments to define conservancy districts for flood control. Controversial elements of the Act gave local governments the right to raise funds for the civil engineering efforts through taxes, and granted eminent domain to support the purchase or condemnation of the necessary lands for dams, basins, and flood plains.[1] On March 17, 1914, the governor signed the Ohio Conservancy Act, which allowed for the establishment of conservancy districts with the authority to implement flood control projects. The Act became the model for other states, such as Indiana, New Mexico, and Colorado.[22] Ohio's Upper Scioto Conservancy District was the first to form in February 1915.[22] The Miami Conservancy District, which includes Dayton and surrounding communities,[8] was the second, formed in June 1915.[22] Morgan was appointed as the Miami Conservancy District's first president. The constitutionality of the Act was challenged in Orr v. Allen, a lawsuit brought by a landowner impacted by eminent domain, and attempts were made to amend it through the Garver-Quinlisk bills. Legal battles continued from 1915 to 1919 and reached the U.S. Supreme Court, but the law was upheld.[24]

Miami Conservancy District's flood project

The Miami Conservancy District began construction of its flood control system in 1918. Since 1922, when the project was completed at a cost in excess of $32 million, it has kept Dayton from flooding as significantly as it did in 1913.[8][22] Since its completion, the Miami Conservancy District has protected the Dayton area from flooding over 1,500 times.[25] Ongoing expenses for maintaining the district comes from property tax assessments collected annually from all property holders in the district. Properties closer to the river channel and the natural flood plain pay more than properties further away.[26]

Osborn, Ohio

The small village of Osborn, Ohio, which had little damage from the flood, was affected by the flood's aftermath. The village lay in the area designated to become part of the Huffman flood plain. The mainline tracks of the Erie Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, and the Ohio Electric Railway running through Osborn were moved several miles south to run through Fairfield, Ohio.

The citizens of Osborn decided to move their homes instead of abandoning them, and almost 400 homes were moved three miles (5 km) to new foundations along Hebble Creek next to Fairfield. Some years later, the two towns merged to create Fairborn, Ohio, with the name selected to reflect the merging of the two villages.[5]

Other losses

Orville and Wilbur Wright, who made their home in Dayton, had flown for the first time a decade earlier, and were busy creating the aviation industry in their workshop and the area around Huffman Prairie, adjacent to the planned Huffman Dam. They had meticulously documented the flight efforts using a camera, and had an extensive collection of photographic plates. One unexpected loss in the flood was water damage that created cracks and blemishes on the photographic plates. Prints made from the plates prior to the flood were better quality than the prints made after the flood.[27] However, few prints had been made off of the glass negatives before 1913, as the Wrights kept evidence of their pioneering work a secret from the public and the images, and thus those that were lost in the flood were irreplaceable.

By this time, there were few canals in Ohio still in operation, but many of them remained intact across the state. To alleviate flooding conditions, local government leaders used dynamite to remove the locks in the canals to allow the water to flow unimpeded. This destruction ended the era of canal transportation in Ohio history.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 "The History of the MCD: The Conservancy Act". Miami Conservancy District. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ J. Warren Smith (1913). The Floods of 1913 in the rivers of the Ohio and the lower Mississippi Valleys. Washington: Government Printing Office. p. 117.

- 1 2 3 "The History of the MCD: The Great Flood of 1913". Miami Conservancy District. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 J. David Rogers. "The 1913 Dayton Flood and the Birth of Modern Flood Control Engineering in the United States" (PDF). Natural Hazards Mitigation Institute:University of Missouri-Rolla. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diana G. Cornelisse (September 10, 1991). "The Foulois House: Its Place in the History of the Miami Valley and American Aviation". Wright-Patterson Air Force Base:ASC History Office. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "And the Rains Came: Dayton and the 1913 Flood". Dayton History at the Archive Center. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ Geoff Williams (2013). Washed Away: How the Great Flood of 1913, America’s Most Widespread Natural Disaster, Terrorized a Nation and Changed It Forever. New York: Pegasus Books. p. viii. ISBN 978-1-60598-404-9.

- 1 2 3 Christopher Klein (March 25, 2013). "The Superstorm That Flooded America 100 Years Ago". History. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Trudy E. Bell (November 16, 2012). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: 'An Epidemic of Disasters'". blog. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "The Great Ohio Valley Flood of 1913- 100 Years Later" (pdf). Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Andrew Gustin. "Flooding in Indiana: Not "If", but "When"". Indiana Geological Survey. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ The Great Miami River overflowed the levee along Monument Avenue, near the Main Street Bridge, collapsing the levee and sending water through the city's downtown business district, with currents up to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). Another levee burst on the north side of the river, flooding North Dayton and Riverdale. See Trudy E. Bell (December 9, 2012). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: The Villain Who Stole the Flood". blog. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Ruptured gas lines and chemical spills in industrial buildings ignited fires covering several city blocks. See Christopher Klein (March 25, 2013). "The Superstorm That Flooded America 100 Years Ago". History. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Trudy E. Bell (December 9, 2012). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: The Villain Who Stole the Flood". blog. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Williams, p. 204.

- ↑ Williams, p. 208.

- ↑ Trudy E.Bell (February 18, 2013). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: 'Death Rode Ruthless…'". blog. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ An estimate of 467 deaths has been quoted for Ohio, with the official death toll range between 422 and 470. See Williams, p. viii, and Trudy E. Bell (February 18, 2013). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: 'Death Rode Ruthless…'". blog. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Dayton's official death toll is not certain. Ohio's Bureau of Statistics listed eighty-two people, while one flood historian puts the number at ninety-eight and others have reported the city's death toll at 300 or more, but this figure may have included other neighborhoods and cities. See Williams, p. 303.

- ↑ "The Flood Menace: The Debate Over Flood Protection in Ohio's Miami Valley Illustrated Through Political Cartoons". Wright State University Libraries: Special Collections and Archives. Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- 1 2 "Flood of 1913". Ohio History Central. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Great Flood of 1913, 100 Years Later: 1913 vs. Today". Silver Jackets. 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Trudy E. Bell (January 20, 2013). "'Our National Calamity': The Great Easter 1913 Flood: Morgan's Cowboys". blog. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ "The Flood Menace: Opposition to Vonderheide Conservancy Act". Wright State University Libraries: Special Collections and Archives. Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ "The History of the MCD: Construction". Miami Conservancy District. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Flood Protection: Assessments". Miami Conservancy District. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

- ↑ "The Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of Congress: Photography and the Wright Brothers". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 13, 2007.

Primary sources

- 1913 Flood Collection (MS-016). Dayton Metro Library, Dayton, Ohio. "View online finding aid.". Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- 1913 Dayton Flood Collection. University of Dayton University Archives and Special Collections, Dayton, Ohio. "View online collection.". Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- Original film footage of 1913 Flood, part of the Glenn R. Walters Collection. University of Dayton University Archives and Special Collections, Dayton, Ohio. "View film footage.". Retrieved March 25, 2013.

External links

- Dayton and the 1913 Flood

- Miami Conservancy District

- Ohio History Central:Vonderheide Act

- FindLaw: Orr v. Allen

- The 1913 Flood