HMS Terror (1813)

HMS Terror in the Arctic | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Terror |

| Ordered: | 30 March 1812 |

| Builder: | Robert Davy, Topsham, Devon |

| Laid down: | September 1812 |

| Launched: | 19 June 1813 |

| Completed: | By 31 July 1813 |

| Fate: | Abandoned in Victoria Strait, Canada, 22 April 1848 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Vesuvius-class bomb vessel |

| Tons burthen: | 325 (bm) |

| Length: | 102 ft (31.09 m) |

| Beam: | 27 ft (8.23 m) |

| Installed power: | 30 hp (22 kW) nhp [1] |

| Propulsion: | |

| Complement: | 67 |

| Armament: |

|

| Official name | Erebus and Terror National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1992 |

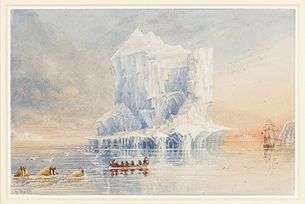

HMS Terror was a bomb vessel constructed for the Royal Navy in 1813. She participated in several battles of the War of 1812, including the bombardment of Fort McHenry. Later converted into a polar exploration ship, she participated in George Back's Arctic expedition of 1836–1837, the Ross expedition of 1839 to 1843, and Sir John Franklin's ill-fated attempt to force the Northwest Passage in 1845, during which she was lost with all hands along with HMS Erebus.

On 12 September 2016, the Arctic Research Foundation announced that the wreck of Terror had been found in Nunavut's Terror Bay, off the southwest coast of King William Island. The wreck was discovered 92 km (57 mi) south of the location where the ship was reported abandoned, and some 50 km (31 mi) from the wreck of HMS Erebus, discovered in 2014.

Early history and military service

HMS Terror was a Vesuvius-class bomb ship built over two years at the Davy shipyard in Topsham, Devon, for the Royal Navy. Her deck was 31 m (102 ft) long, and the ship measured 325 tons burthen. The vessel was armed with two mortars and ten cannons, and was launched in June 1813.[2]

Terror saw service in the War of 1812 against the United States.[3] Under the command of John Sheridan, she took part in the bombardment of Stonington, Connecticut, on 9–12 August 1814. She also fought in the Battle of Baltimore in September 1814 and participated in the bombardment of Fort McHenry; the latter attack inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem that eventually became known as "The Star-Spangled Banner".[3] In January 1815, still under Sheridan's command, Terror was involved in the Battle of Fort Peter and the attack on St. Marys, Georgia.[4]

After the war, Terror was laid up until March 1828, when she was recommissioned for service in the Mediterranean Sea, but was removed from active service when she underwent repairs for damage suffered near Lisbon, Portugal.[5]

Early polar exploration service

In the mid-1830s, Terror was refitted as a polar exploration vessel. Her design as a bomb ship meant she had a strong framework to resist the recoil of her mortars; thus, she could withstand polar sea ice, as well.[2]

Back expedition

In 1836, command of Terror was given to Captain George Back for an Arctic expedition to Hudson Bay.[2][3] The expedition aimed to enter Repulse Bay, where it would send out landing parties to ascertain whether the Boothia Peninsula was an island or a peninsula. Terror was trapped by ice near Southampton Island, and did not reach Repulse Bay. At one point, the ice forced her 12 m (39 ft) up the face of a cliff.[5] She was trapped in the ice for ten months.[3] In the spring of 1837, an encounter with an iceberg further damaged the ship. She nearly sank on her return journey across the Atlantic,[3] and was in a sinking condition by the time Back was able to beach the ship on the coast of Ireland.[5]

Ross expedition

Terror was repaired and assigned in 1839 to a voyage to the Antarctic along with Erebus under the overall command of James Clark Ross.[2][3] Francis Crozier was commander of Terror on this expedition, as well as second-in-command to Ross.[2] The expedition spanned three seasons from 1840 to 1843 during which Terror and Erebus made three forays into Antarctic waters, traversing the Ross Sea twice, and sailing through the Weddell Sea southeast of the Falkland Islands. The dormant volcano Mount Terror on Ross Island was named after the ship by the expedition commander.[2][5]

Franklin expedition

Before leaving on the Franklin expedition, both Erebus and Terror underwent heavy modifications for the journey.[3] They were both outfitted with steam engines, taken from former London and Greenwich Railway steam locomotives. Rated at 25 hp (19 kW), each could propel its ship at 4 knots (7.4 km/h). The pair of ships became the first Royal Navy ships to have steam-powered engines and screw propellers.[3] Twelve days' supply of coal was carried.[6] Iron plating was added fore and aft on the ships' hulls to make them more resistant to pack ice, and their decks were cross-planked to distribute impact forces.[3] Along with Erebus, Terror was stocked with supplies for their expedition, which included among other items: two tons of tobacco, 8,000 tins of preserves, and 7,560 L (1,660 imp gal; 2,000 US gal) of liquor. Terror's library had 1,200 books, and the ship's berths were heated via ducts that connected them to the stove.[3]

Their voyage to the Arctic was with Sir John Franklin in overall command of the expedition in Erebus, and Terror again under the command of Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier. The expedition was ordered to gather magnetic data in the Canadian Arctic and complete a crossing of the Northwest Passage, which had already been charted from both the east and west, but never entirely navigated. It was planned to last three years.[3]

The expedition sailed from Greenhithe, Kent, on 19 May 1845, and the ships were last seen entering Baffin Bay in August 1845.[5] The disappearance of the Franklin expedition set off a massive search effort in the Arctic and the broad circumstances of the expedition's fate were revealed during a series of expeditions between 1848 and 1866. Both ships had become icebound and were abandoned by their crews, all of whom died of exposure and starvation while trying to trek overland to Fort Resolution, a Hudson's Bay Company outpost 600 mi (970 km) to the southwest. Subsequent expeditions up until the late 1980s, including autopsies of crew members, revealed that their canned rations may have been tainted by both lead and botulism. Oral reports by local Inuit that some of the crew members resorted to cannibalism were at least somewhat supported by forensic evidence of cut marks on the skeletal remains of crew members found on King William Island during the late 20th century.[7][8]

A British transport ship, Renovation, spotted two ships on a large ice floe off the coast of Newfoundland in April 1851. The identities of the two ships have never been confirmed. It was suggested that these ships may have been Erebus and Terror. Likely, they were in fact abandoned whaling ships.[9]

Discovery of the wreckage

On 15 August 2008, Parks Canada, an agency of the Government of Canada, announced a C$75,000 six-week search, deploying the icebreaker CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier with the goal of finding the two ships. The search was also intended to strengthen Canada's claims of sovereignty over large portions of the Arctic.[10] Further attempts to locate the ships were undertaken in 2010, 2011, and 2012,[11] all of which failed to locate the ships' remains.

On 8 September 2014, it was announced that the wreckage of one of Franklin's ships was found on 7 September using a remotely operated underwater vehicle recently acquired by Parks Canada.[12][13] On 1 October 2014, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that the remains were that of Erebus.[14]

On 12 September 2016, a team from the Arctic Research Foundation announced that a wreck close to Terror's description had been located on the southern coast of King William Island in the middle of Terror Bay (68°54′N 98°56′W / 68.900°N 98.933°W), at a depth of 69–79 ft (21–24 m).[8][15] The remains of the ships are designated a National Historic Site of Canada with the exact location withheld to preserve the wrecks and prevent looting.[16]

Sammy Kogvik, an Inuit hunter and member of the Canadian Rangers who joined the crew of the Arctic Research Foundation's Martin Bergmann, recalled an incident from seven years earlier in which he encountered what appeared to be a mast jutting from the ice. With this information, the ship's destination was changed from Cambridge Bay to Terror Bay, where researchers located the wreck in just 2.5 hours.[15][17][18] According to Louie Kamookak, a resident of nearby Gjoa Haven and a historian on the Franklin expedition, Parks Canada had ignored the stories of locals that suggested that the wreck of Terror was in its namesake bay, despite many modern stories of sightings by hunters and from airplanes.[17]

The wreck was found in excellent condition. A wide exhaust pipe that rose from the outer deck was pivotal in identifying the ship. It was located in the same location where the smokestack from the Terror's locomotive engine had been installed. The wreck was nearly 100 km (62 mi) south of where historians thought its final resting place was, calling into question the previously accepted account of the fate of the sailors, that they died while trying to walk out of the Arctic to the nearest Hudson's Bay Company trading post.[8]

The location of the wreckage, and evidence in the wreckage of anchor usage, raised the possibility that some of the sailors had attempted to reman the ship and sail her home,[8] possibly on orders from Crozier.[17]

Legacy

HMS Terror is featured in fictional works that use the Franklin expedition in their backstories, such as:

- In Mordecai Richler's Solomon Gursky Was Here, Ephraim Gursky survives the expedition and lives to pass on his Judaism and Yiddish to some of the local Inuit.[7]

- In Clive Cussler's 2008 novel Arctic Drift, Erebus and Terror contain a mysterious silver metal which holds the key to solving the characters' mystery.

- HMS Terror is also the subject of the 2007 novel The Terror by American author Dan Simmons.

Mount Terror on Ross Island near Antarctica was named for the ship by Captain Ross, who also named a nearby and slightly taller peak to the west, Mount Erebus. Terror Bay on King William Island was named in 1910,[19] long before the discovery of the wreck there.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Bourne, John (1852). "Appendix, Table I: Dimensions Of Screw Steam Vessels In Her Majesty's Navy". A treatise on the screw propeller: with various suggestions of improvement. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. i.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "HMS Terror". Parks Canada. 4 August 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pope, Alexandra (12 September 2016). "Five interesting facts about the HMS Terror". Canadian Geographic. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ James, William (1835). The Naval History of Great Britain. 6. London: James Ridgway. p. 235.

On the 14th, the combined forces [at Point St Peter], accompanied by the bomb vessels Devastation and Terror..ascended the river to St Marys

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 139–140. ISBN 0-395-98415-7.

- ↑ Gow, Harry (12 February 2015). "British loco boiler at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean". Heritage Railway. Horncastle: Mortons Media Group Ltd (199): 84. ISSN 1466-3562.

- 1 2 Gopnik, Adam (24 September 2014). "Canada Rediscovers the Mythos of the Franklin Expedition". The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson, Paul (2016-09-12). "Ship found in Arctic 168 years after doomed Northwest Passage attempt". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ↑ "Arctic Blue Books - British Parliamentary Papers Abstract, 1852k". University of Manitoba Libraries - Archives and Special Collections. 1852.

- ↑ Boswell, Randy (2008-01-30). "Parks Canada to lead new search for Franklin ships". Windsor Star. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ "2012 search Expedition for Franklin's ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror". Office of the Prime Minister (Canada). 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "Sir John Franklin: Fabled Arctic ship found". BBC News. 2014-09-09.

- ↑ "Lost Franklin expedition ship found in the Arctic". CBC News. 2014-09-09.

- ↑ "Franklin expedition ship found in Arctic ID'd as HMS Erebus". CBC News. 2014-10-01.

- 1 2 Pringle, Heather (13 September 2016). "Unlikely Tip Leads to Discovery of Historic Shipwreck". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Erebus and Terror. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 29 October 2013. ; "National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan". Parks Canada. 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2013-08-30.; "National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan map". Parks Canada. 2009-04-15. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- 1 2 3 Sorensen, Chris (14 September 2016). "HMS Terror: How the final Franklin ship was found". Maclean's. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Barton, Katherine (15 September 2016). "No camera, no proof: Why Sammy Kogvik didn't tell anyone about HMS Terror find". CBC News. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Terror Bay", Geographic Names Board of Canada, Natural Resources Canada

References

- Beardsly, Martyn: Deadly Winter: The Life of Sir John Franklin. ISBN 1-55750-179-3.

- Beattie, Owen: Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition. ISBN 1-55365-060-3.

- Berton, Pierre: The Arctic Grail. ISBN 0-670-82491-7.

- Cookman, Scott: Ice Blink: The Tragic Fate of Sir John Franklin's Lost Polar Expedition. ISBN 0-471-37790-2.

- James, William (1827). The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 6, 1811 – 1827. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-910-7.

- McGregor, Elizabeth: The Ice Child.

- Simmons, Dan: The Terror (Fictionalized account of the Franklin expedition). ISBN 0-593-05762-7 (UK H/C).

- Smith, Michael: Captain Francis Crozier: The Last Man Standing?. ISBN 1-905172-09-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Terror (ship, 1813). |

- Erebus and Terror

- Bryk, William (2002-01-31). "Central Park Still Awaits the British". New York Press. 15 (5). Archived from the original on 2002-02-02. New York Press article describing Terror's bombardment of Stonington

- Ships of the World listing

- Naval History of Great Britain, volume VI

- The Wreck Of HMS Erebus: How A Landmark Discovery Triggered A Fight For Canada’s History, Buzzfeed