Henry Lawson

| Henry Lawson | |

|---|---|

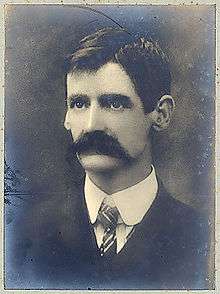

Henry Lawson, circa 1902 | |

| Born |

17 June 1867 Grenfell goldfields, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died |

2 September 1922 (aged 55) Sydney, Australia |

| Occupation | Author, poet, balladist |

| Spouse(s) | Bertha Marie Louise Bredt |

| Children | Joseph, Bertha |

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922)[1] was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's "greatest short story writer".[2] He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist Louisa Lawson.

Early life

Henry Lawson was born 17 June 1867 in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. His father was Niels Hertzberg Larsen, a Norwegian-born miner. Niels Larsen went to sea at 21 and arrived in Melbourne in 1855 to join the gold rush, along with partner William Henry John Slee.[1] Lawson's parents met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee, Gloucester County, New South Wales). Niels and Louisa Albury (1848–1920) married on 7 July 1866 when he was 32 and she 18. On Henry's birth, the family surname was Anglicised and Niels became Peter Lawson. The newly married couple were to have an unhappy marriage. Louisa, after family-raising, took a significant part in women's movements, and edited a women's paper called The Dawn (published May 1888 to July 1905). She also published her son's first volume, and around 1904 brought out a volume of her own, Dert and Do, a simple story of 18,000 words. In 1905 she collected and published her own verses, The Lonely Crossing and other Poems. Louisa likely had a strong influence on her son's literary work in its earliest days.[3] Peter Lawson's grave (with headstone) is in the little private cemetery at Hartley Vale, New South Wales, a few minutes' walk behind what was Collitt's Inn.

Lawson attended school at Eurunderee from 2 October 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time. It left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. However, his master John Tierney was kind and did all he could for Lawson, who was quite shy.[3] Lawson later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales around 8 km away; the master there, Mr Kevan, would teach Lawson about poetry. Lawson was a keen reader of Dickens and Marryat and novels such as Robbery Under Arms and For the Term of His Natural Life; an aunt had also given him a volume by Bret Harte. Reading became a major source of his education because, due to his deafness, he had trouble learning in the classroom.

In 1883, after working on building jobs with his father in the Blue Mountains, Lawson joined his mother in Sydney at her request. Louisa was then living with Henry's sister and brother. At this time, Lawson was working during the day and studying at night for his matriculation in the hopes of receiving a university education. However, he failed his exams. At around 20 years of age Lawson went to the eye and ear hospital in Melbourne but nothing could be done for his deafness.[3]

In 1890 he began a relationship with Mary Gilmore.[4] She writes of an unofficial engagement and Lawson's wish to marry her, but it was broken by his frequent absences from Sydney. The story of the relationship is told in Anne Brooksbank's play All My Love.[5][6]

In 1896, Lawson married Bertha Bredt, Jr., daughter of Bertha Bredt, the prominent socialist. The marriage ended very unhappily.[7] They had two children, son Jim (Joseph) and daughter Bertha.

Poetry and prose writing

Henry Lawson's first published poem was 'A Song of the Republic' which appeared in The Bulletin, 1 October 1887; his mother's republican friends were an influence. This was followed by 'The Wreck of the Derry Castle' and then 'Golden Gully.' Prefixed to the former poem was an editorial 'note:

| “ | In publishing the subjoined verses we take pleasure in stating that the writer is a boy of 17 years, a young Australian, who has as yet had an imperfect education and is earning his living under some difficulties as a housepainter, a youth whose poetic genius here speaks eloquently for itself. | ” |

Lawson was 20 years old, not 17.[3]-

In 1890-1891 Lawson worked in Albany.[8] He then received an offer to write for the Brisbane Boomerang in 1891, but he lasted only around 7–8 months as the Boomerang was soon in trouble. While in Brisbane he contributed to William Lane's Worker; he later angled for an editorial position with the similarly-named Worker of Sydney, but was unsuccessful.[3] He returned to Sydney and continued to write for the Bulletin which, in 1892, paid for an inland trip where he experienced the harsh realities of drought-affected New South Wales.[9] He also worked as a roustabout in the woolshed at Toorale Station.[10] This resulted in his contributions to the Bulletin Debate and became a source for many of his stories in subsequent years.[1] Elder writes of the trek Lawson took between Hungerford and Bourke as "the most important trek in Australian literary history" and says that "it confirmed all his prejudices about the Australian bush. Lawson had no romantic illusions about a 'rural idyll'."[11] As Elder continues, his grim view of the outback was far removed from "the romantic idyll of brave horsemen and beautiful scenery depicted in the poetry of Banjo Paterson".[12]

Lawson's most successful prose collection is While the Billy Boils, published in 1896.[13] In it he "continued his assault on Paterson and the romantics, and in the process, virtually reinvented Australian realism".[9] Elder writes that "he used short, sharp sentences, with language as raw as Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver. With sparse adjectives and honed-to-the-bone description, Lawson created a style and defined Australians: dryly laconic, passionately egalitarian and deeply humane."[9] Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush, such as the desolate "Past Carin'", and is considered by some to be among the first accurate descriptions of Australian life as it was at the time. "The Drover's Wife" with its "heart-breaking depiction of bleakness and loneliness" is regarded as one of his finest short stories.[14] It is regularly studied in schools and has often been adapted for film and theatre.[15]

_(13981404964).jpg)

Lawson was a firm believer in the merits of the sketch story, commonly known simply as 'the sketch,' claiming that "the sketch story is best of all."[16] Lawson's Jack Mitchell story, On The Edge Of A Plain, is often cited as one of the most accomplished examples of the sketch.[17]

Like the majority of Australians, Lawson lived in a city, but had had plenty of experience in outback life, in fact, many of his stories reflected his experiences in real life. In Sydney in 1898 he was a prominent member of the Dawn and Dusk Club, a bohemian club of writer friends who met for drinks and conversation.

Later years

In 1903 he bought a room at Mrs Isabel Byers' Coffee Palace in North Sydney. This marked the beginning of a 20-year friendship between Mrs Byers and Lawson. Despite his position as the most celebrated Australian writer of the time, Lawson was deeply depressed and perpetually poor. He lacked money due to unfortunate royalty deals with publishers. His ex-wife repeatedly reported him for non-payment of child maintenance, resulting in gaol terms. He was gaoled at Darlinghurst Gaol for drunkenness and non-payment of child support, and recorded his experience in the haunting poem "One Hundred and Three" - his prison number - which was published in 1908. He refers to the prison as "Starvinghurst Gaol" because of the meagre rations given to the inmates.[18]

At this time, Lawson became withdrawn, alcoholic, and unable to carry on the usual routine of life.

Mrs Byers (née Ward) was an excellent poet herself and although of modest education, had been writing vivid poetry since her teens in a similar style to Lawson's. Long separated from her husband and elderly, Mrs Byers was, at the time she met Lawson, a woman of independent means looking forward to retirement. Byers regarded Lawson as Australia's greatest living poet, and hoped to sustain him well enough to keep him writing. She negotiated on his behalf with publishers, helped to arrange contact with his children, contacted friends and supporters to help him financially, and assisted and nursed him through his mental and alcohol problems. She wrote countless letters on his behalf and knocked on any doors that could provide Henry with financial assistance or a publishing deal.[18][19]

It was in Mrs Isabel Byers' home that Henry Lawson died, of cerebral hemorrhage, in Abbotsford, Sydney in 1922. He was given a state funeral. His death registration on the NSW Births, Deaths & Marriages index[20] is ref. 10451/1922 and was recorded at the Petersham Registration District.[21] It shows his parents as Peter and Louisa. His funeral was attended by the Prime Minister Billy Hughes and the Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang (who was the husband of Lawson's sister-in-law Hilda Bredt), as well as thousands of citizens. He is interred at Waverley Cemetery. Lawson was the first person to be granted a New South Wales state funeral (traditionally reserved for Governors, Chief Justices, etc.) on the grounds of having been a 'distinguished citizen'.[18]

Honours

A bronze statue of Lawson accompanied by a swagman, a dog and a fencepost (reflecting his writing) stands in The Domain, Sydney.[22] The Henry Lawson Memorial committee raised money through public donation to commission the statue by sculptor George Washington Lambert in 1927. The work was unveiled on 28 July 1931 by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game.[23]

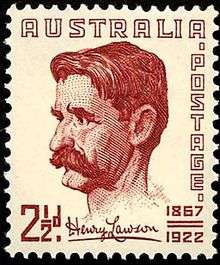

In 1949 Lawson was the subject of an Australian postage stamp.

He was featured on the first (paper) Australian ten dollar note issued in 1966 when decimal currency was first introduced into Australia. Lawson was pictured against scenes from the town of Gulgong in NSW.[24] This note was replaced by a polymer note in 1993; the polymer series had different people featured on the notes.

Bibliography

Collections

- Short Stories in Prose and Verse (1894) - short stories, prose, poetry

- While the Billy Boils (1896) - short stories

- In the Days When the World was Wide and Other Verses (1896) - poetry

- Verses, Popular and Humorous (1900) - poetry

- On the Track (1900) - short stories

- Over the Sliprails (1900) - short stories

- On the Track, and, Over the Sliprails (1900) - short stories

- Popular Verses (1900) - poetry

- Humorous Verses (1900) - poetry

- The Country I Come From (1901) - short stories

- Joe Wilson and His Mates (1901) - short stories

- Children of the Bush (1902) - short stories, prose, poetry

- When I Was King and Other Verses (1905) - poetry

- The Elder Son (1905) - poetry

- When I Was King (1905) - poetry

- The Romance of the Swag (1907) - short stories, prose

- Send Round the Hat (1907) - short stories

- The Skyline Riders and Other Verses (1910) - poetry

- The Rising of the Court and Other Sketches in Prose and Verse (1910) - short stories, prose, poetry

- For Australia and Other Poems (1913) - poetry

- Triangles of Life and Other Stories (1913) - short stories

- My Army, O, My Army! and Other Songs (1915) - poetry

- Song of the Dardanelles and Other Verses (1916) - poetry

- Selected Poems of Henry Lawson (1918) - poetry

Posthumous collections

- Poems of Henry Lawson (1973)

- The Best of Henry Lawson for Young Australians (1973)

- The Drover's Wife and Other Stories (1974)

- The World of Henry Lawson (1974)

- The Poems of Henry Lawson (1975)

- Poems of Henry Lawson : Volume Two (1975)

- Favourite Stories (1976)

- Henry Lawson : favourite verse (1978)

- Henry Lawson Poems (1979)

- Henry Lawson's Mates : The Complete Stories of Henry Lawson (1979)

- The Essential Henry Lawson : The Best Works of Australia's Greatest Writer (1982)

- A Camp-Fire Yarn: Henry Lawson Complete Works 1885-1900 (1984)

- A Fantasy of Man: Henry Lawson Complete Works 1901-1922 (1984)

- Henry Lawson Favourites (1984)

- Henry Lawson, The Master Story-Teller : Prose Writings (1984)

- The Penguin Henry Lawson Short Stories (1986)

- The Songs of Henry Lawson (1989)

- The Roaring Days (1994) (aka The Henry Lawson Collection Vol. 1)

- On the Wallaby Track (1994) (aka The Henry Lawson Collection Vol. 2)

Popular poems, short stories and sketches

- "Australian Loyalty" (essay, 1887)

- "Andy's Gone with Cattle" (poem, 1888)

- "United Division" (essay, 1888)

- "The Teams" (poem, 1889)

- "A Neglected History" (essay)

- "Freedom on the Wallaby" (poem, 1891)

- "The Babies of Walloon (poem, 1891)

- "The Bush Undertaker" (short story, 1892)

- "The City Bushman" (poem, 1892)

- "Up The Country" (poem, 1892)

- "The Grog-an'-Grumble Steeplechase" (1892)

- "The Drover's Wife" (short story, 1892)

- "Saint Peter" (poem, 1893)

- "The Union Buries Its Dead" (short story, 1893)

- "Steelman's Pupil" (short story, 1895)

- "The Geological Spieler" (short story, 1896)

- "The Iron-Bark Chip" (short story, 1900)

- "The Loaded Dog" (short story, 1901)

- "A Child in the Dark, and a Foreign Father" (short story, 1902)

- "Triangles of Life, and other stories" (short stories, 1916)

- "Scots of the Riverina" (poem, 1917)

Recurring characters

Lawson in Popular Culture

- While the Billy Boils by Beaumont Smith

- Trooper Campbell by Raymond Longford

- Taking his Chance by Raymond Longford

- Bulletin Debate

- Recording of Henry Lawson's works by actor Jack Thompson[25]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Matthews, Brian. "Lawson, Henry (1867–1922)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ Elder, Bruce (2008), "In Lawson's tracks [The Henry Lawson Trail from Bourke (NSW) to Hungerford (Qld). Paper in: Re-imagining Australia. Schultz, Julianne (ed.).]", Griffith Review (19): 115, ISBN 978-0-7333-2281-5, ISSN 1448-2924

- 1 2 3 4 5 Percival Serle (1949). "Lawson, Henry (1867 - 1922)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ↑ Wilde, W. H. Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ "Literary lovers: Henry Lawson and Mary Gilmore". 16 July 2015.

- ↑ "All My Love - Glen Street Theatre".

- ↑ Falkiner, Suzanne (1992), Wilderness, Simon & Schuster, p. 64, ISBN 978-0-7318-0144-2

- ↑ Falkiner, Suzanne (1992), Wilderness, Simon & Schuster, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-7318-0144-2

- 1 2 3 Elder, Bruce (2008), "In Lawson's tracks [The Henry Lawson Trail from Bourke (NSW) to Hungerford (Qld). Paper in: Re-imagining Australia. Schultz, Julianne (ed.).]", Griffith Review (19): 113, ISBN 978-0-7333-2281-5, ISSN 1448-2924

- ↑ "Toorale". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Elder, Bruce (2008), "In Lawson's tracks [The Henry Lawson Trail from Bourke (NSW) to Hungerford (Qld). Paper in: Re-imagining Australia. Schultz, Julianne (ed.).]", Griffith Review (19): 95, ISBN 978-0-7333-2281-5, ISSN 1448-2924

- ↑ Elder, Bruce (2008), "In Lawson's tracks [The Henry Lawson Trail from Bourke (NSW) to Hungerford (Qld). Paper in: Re-imagining Australia. Schultz, Julianne (ed.).]", Griffith Review (19): 96, ISBN 978-0-7333-2281-5, ISSN 1448-2924

- ↑ Falkiner, Suzanne (1992), Wilderness, Simon & Schuster, p. 63, ISBN 978-0-7318-0144-2

- ↑ Elder (2008) p. 113

- ↑ Wells, Rachel. "Keeping bush ballads alive and well". The Age. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Lawson, Henry (1984). "Three or Four Archibalds and the Writer". In Leonard Cronin. A fantasy of man: Henry Lawson complete works, 1901-1922. Lansdowne. p. 987. ISBN 0701818751.

- ↑ Lawson, Henry (1986). Introduction by John Barnes, ed. The Penguin Henry Lawson short stories. Penguin. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0140092153.

- 1 2 3 "Henry Lawson – the man, his work and the legend". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Lawson, Olive (2004). The Good Wards of Windsor. Deerubbin. pp. 49–53. ISBN 0975099132.

- ↑ http://www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/cgi-bin/Index/IndexingOrder.cgi/search?event=births

- ↑ "NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages". Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Blogger user: jim. "The Domain, Henry Lawson statue". Sydney - City and Suburbs. Blogger. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ "George W. Lambert retrospective". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ "Museum of Australian Currency Notes". Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "The Campfire Yarns of Henry Lawson - Fine Poets".

References

- Elder, Bruce (2008) "In Lawson's Tracks" in Griffith Review (19): 93-95, 113-115, Autumn 2008

- Falkiner, Suzanne (1992) Wilderness (The Writers' Landscape), Sydney, Simon & Schuster

Further reading

- Wright, Judith (1967). Henry Lawson. Great Australians. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Lawson. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Lawson |

- Works by Henry Lawson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Henry Lawson at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Page of Henry Lawson at Poeticous.com

- Works by or about Henry Lawson at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Lawson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Henry Lawson - Essays, Short Stories and Verse Collections

- Henry Lawson and Louisa Lawson Online Chronology

- Jack Thompson reads The Poems of Henry Lawson

- Lawson, Henry (1867-1922) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for Henry Lawson

- Poetry Archive: 125 poems of Henry Lawson

- The Drover’s Wife at jbrowley.com