History of the Nintendo Entertainment System

Nintendo's 8-bit video game console, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), known in Japan as the Family Computer (Japanese: ファミリーコンピュータ Hepburn: Famirī Konpyūta) or Famicom (ファミコン Famikon), was introduced after the video game crash of 1983, and was instrumental in revitalizing the industry. It enjoyed a long lifespan and dominated the market during the rest of the decade. Facing obsolescence in 1990 with the advent of 16-bit consoles, it was supplanted by its successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, but support and production continued until 1995. After its discontinuation, interest in the NES has since been renewed by collectors and emulators, including Nintendo's own Virtual Console platform.

Origins (1982–1984)

The video game market experienced a period of rapid growth and unprecedented popularity in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Consoles such as the Atari 2600 and the Intellivision proved to be wildly popular, and many third-party developers arose in their wake to exploit the growing industry. Nintendo was one such development studio, and, by 1982 had found success with a number of arcade games, such as Donkey Kong, which was in turn ported to, and packaged with the ColecoVision console in North America.

Led by Masayuki Uemura, Nintendo's R&D team had been secretly working on a system since 1980, ambitiously targeted to be less expensive than its competitors, yet with performance that could not be surpassed by its competitors for at least a year.[1] Uemura initially thought of using a modern 16-bit CPU, but instead settled on the inexpensive MOS Technology 6502, supplementing it with a custom graphics chip (the Picture Processing Unit).[2] To keep costs down, suggestions of including a keyboard, modem, and floppy disk drive were rejected, but expensive circuitry was added to provide a versatile 15-pin expansion port connection on the front of the console for future add-on functionality such as peripheral devices.

The keyboard, Famicom Modem, and Famicom Disk System would later be released as add-on peripherals, all utilizing the Famicom expansion port. Other peripheral devices connecting via the expansion port would include the Famicom Light Gun, Family Trainer, and various specialized controllers. Many such devices would be produced for the console, though many of them, including the Famicom 3D System and Famicom Disk System, were never released outside Japan.

Launching on July 15, 1983,[3] the Family Computer (commonly known by the Japanese-English term Famicom) is an 8-bit console using interchangeable cartridges.[2]

The Famicom was released in Japan on July 15, 1983, for ¥14,800. The launch titles for the console were Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Junior, and Popeye. The console itself was intentionally designed to look like a toy, with a bright red-and-white color scheme and two hardwired gamepads that are stored visibly at the sides of the unit.

Though selling well in its early months,[4] many Famicom units reportedly froze during gameplay. After tracing the problem to a faulty circuit, Nintendo recalled all Famicom systems just before the holiday shopping season, and temporarily suspended production of the system while the concerns were addressed, costing Nintendo millions of dollars. The Famicom was subsequently reissued with a new motherboard.[5] The Famicom easily outsold its primary competitor, the Sega SG-1000. By the end of 1984 Nintendo had sold over 2.5 million Famicoms in the Japanese market.[6]

Going international (1984–1987)

Marketing negotiations with Atari (1983)

"In the early '80s, Atari debated whether to go with the internally developed successor to the 2600 or a new console that Nintendo wanted us to market. Regrettably, it was my decision not to license the Nintendo system."

—Atari engineer, Steve Bristow[7]

Bolstered by its success in Japan, Nintendo soon turned its attention to foreign markets. As a new console manufacturer, Nintendo had to convince a skeptical public to embrace its system. To this end, Nintendo entered into negotiations with Atari to release the Famicom outside Japan[8] as the "Nintendo Enhanced Video System".[9] Though the two companies reached a tentative agreement, with final contract papers to be signed at the 1983 Summer Consumer Electronics Show (CES), Atari refused to sign at the last minute, after seeing Coleco, one of its main competitors in the market at that time,[6] demonstrating a prototype of Donkey Kong for its forthcoming Coleco Adam home computer system. Coleco had licensed Donkey Kong for the ColecoVision home console, but Atari had the exclusive computer license for the game. Although the game had been originally produced for the ColecoVision and could thus automatically be played on the backward compatible Adam computer, Atari took the demonstration as a sign that Nintendo was also dealing with Coleco. Though the issue was cleared up within a month, by then Atari's financial problems stemming from the North American video game crash of 1983 left the company unable to follow through with the deal.[10]

North America

Advanced Video System home computer (1984)

.jpg)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nintendo Advanced Video System. |

Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi said in 1986, "Atari collapsed because they gave too much freedom to third-party developers and the market was swamped with rubbish games."[12] After the deal with Atari failed, Nintendo proceeded alone, designing a Famicom console for release in North America under the name "Nintendo Advanced Video System" (AVS). To keep the software market for its console from becoming similarly oversaturated, Nintendo added a lockout system to obstruct unlicensed software from running on the console, thus allowing Nintendo to enforce strict licensing standards.

After the crash, many American retailers considered video games a passing fad, and greatly reduced sales of such products, or stopped them entirely.[13] To avoid the stigma of video game consoles, Nintendo marketed the AVS as a full home computer,[14] with an included keyboard, cassette data recorder, and a BASIC interpreter software cartridge.[15] The BASIC interpreter would later be sold together with a keyboard as the Family BASIC package, and the cassette deck for data storage would later be released as the Famicom Data Recorder. The AVS also included a variety of computer-style input devices: gamepads, a handheld joystick, a musical keyboard, and the Zapper light gun. The AVS Zapper is hinged, allowing it to straighten out into a wand form, or bend into a gun form. The AVS uses a wireless infrared interface for all its components, including keyboard, cassette deck, and controllers. Most of the peripherals for the Advanced Video System are on display at the Nintendo World Store.[11] The toy-like white-and-red color scheme of the Famicom was replaced with a clean and futuristic grey monochrome design, with the top and bottom portions in different shades, a stripe with black and ribbing along the top, and minor red accents. The AVS also features a boxier design than the Famicom: flat on top, and a bottom half that tapered down to a smaller footprint. The front of the main unit features a compartment for storing the wireless controllers out of sight. Its software carries the Nintendo Seal of Quality to communicate the company's approval.

The AVS was showcased at the 1984 Winter and Summer CES shows,[11] where attendees acknowledged the advanced technology, but responded poorly to the keyboard and wireless functionality.[14][16] Still wary of video game consoles from the crash, retailers did not order any systems.[6] Although Nintendo had sold more than 2.5 million units of the Famicom in Japan by the beginning of 1985, the American video game press was skeptical that the console could have any success in North America, with the March 1985 issue of Electronic Games magazine stating that "the videogame market in America has virtually disappeared" and that "this could be a miscalculation on Nintendo's part."[17] Roger Buoy of Mindscape allegedly said that year, "Hasn't anyone told them that the videogame industry is dead?"[18]

Redesign as the Nintendo Entertainment System (1985)

At the 1985 Summer CES, Nintendo returned with a stripped-down version of the AVS, having abandoned the home computer approach. Nintendo purposefully designed the system so as not to resemble a video game console, and would avoid terms associated with game consoles, using the term "Pak" for cartridge, or "Control Deck" instead of "console". Renamed the "Nintendo Entertainment System" (NES), the new version lacked most of the upscale features added in the AVS, but retained many of its design elements, such as the grey color scheme and boxy design. In avoidance of an obvious video game connotation, NES replaced the top-loading cartridge slot of the Famicom with a front-loading chamber for software cartridges that place the inserted cartridge out of view. The revised design includes design flaws which have the side-effect of making the NES more prone to breakdown. The loading mechanism became notorious for slowly failing. The Famicom's pair of hard-wired controllers was replaced with two custom 7-pin sockets for detachable controllers.[14]

Using another approach to market the system to North American retailers as an "entertainment system", as opposed to a video game console, Nintendo positioned the NES more squarely as a toy, emphasizing accessories such as the Zapper light gun, and more significantly, R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy), a battery-powered robot that responds to special screen flashes with physical actions.[13] Although R.O.B. succeeded in generating retailer attention and interest for the NES, retailers were still unwilling to sign up to distribute the console.[6]

R.O.B. is credited as a significant factor in building initial support for the NES in North America,[6][19] but the accessory itself was not very successful. Its Famicom counterpart, the Famicom Robot, was already failing in Japan at the time of the North American launch, and R.O.B. would sell similarly poorly. Only two games, Gyromite and Stack-Up, were ever produced for the device.

Only after an intense direct campaign by a dedicated "Nintendo SWAT team",[20] including telemarketing and shopping mall demonstrations, as well as a risk-free proposition to retailers, did Nintendo secure enough retailer support (about 500 retailers, including FAO Schwarz) to conduct a market test in New York City. Nintendo agreed to handle all store setup and marketing, extend 90 days credit on the merchandise, and accept returns on unsold inventory. Retailers would pay nothing upfront, and after 90 days would either pay for the merchandise or return it to Nintendo.[11]

North American launch (1985-1986)

Nintendo initiated a limited test launch process prior to nationwide release. The first test launch saw the NES and its initial library of eighteen games[21] released in New York City on October 18, 1985, with an initial shipment of 100,000 systems. Each set included a console, two gamepads, a R.O.B., a Zapper, and the Game Paks Gyromite and Duck Hunt.[22] The library of eighteen[21] launch titles are 10-Yard Fight, Baseball,[21] Clu Clu Land, Duck Hunt, Excitebike, Golf, Gyromite, Hogan's Alley, Ice Climber, Kung Fu, Pinball, Stack-Up, Tennis, Wild Gunman, and Wrecking Crew. Lucas M. Thomas wrote for IGN that he considered the Baseball title to be a prominent key of success at the test launch event.[21]

Sales were encouraging throughout the holiday season, though sources vary on how many consoles were sold then.[6][23] In 1986, Nintendo said it sold nearly 90,000 units in nine weeks during its 1985 New York City test run.[19][24][25] Nintendo added Los Angeles as a test market in February 1986, followed by Chicago and San Francisco, then other top 12 US markets, and nationwide sales in September.[26] It and Sega, which was similarly exporting its Master System to the US, planned to spend $15 million in the fourth quarter of 1986 to market their consoles;[12] later, Nintendo said it planned to spend $16 million and Sega said more than $9 million.[25] Nintendo obtained a distribution deal with toy company Worlds of Wonder, which leveraged its popular Teddy Ruxpin and Lazer Tag products to solicit more stores to carry the console.[13] The largest retailer Sears sold it through its Christmas catalog and the second largest retailer Kmart sold it in 700 stores.[25] Nintendo sold 1.1 million consoles in 1986, estimating that it could have sold 1.4 million if inventory had held out.[27] Nintendo earned $310 million in sales, out of total 1986 video game industry sales of $430 million,[28] compared to total 1985 industry sales of $100 million.[29]

For the nationwide launch, the NES was available in two different packages: The fully featured $249 USD "Deluxe Set" as configured during the New York City launch, and a scaled-down "Control Deck" package which includes two gamepads and a copy of Super Mario Bros.

Europe and Oceania

The NES was also released in Europe, albeit in stages and in a rather haphazard manner. Most of mainland Europe (excluding Italy, Portugal and Spain) received the system in 1986, where it was distributed by various companies. The United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Australia and New Zealand received the system in 1987, where it was distributed by Mattel.[30] In Europe, the NES received a less enthusiastic response than it had elsewhere, and Nintendo lagged in market and retail penetration (though the console did see more success later on in its life). The NES did outsell the Master System in Australia, though by a much smaller margin than in North America.[31]

South Korea

In South Korea, the hardware was licensed to Hyundai Electronics, which marketed it as the Comboy. After World War II, the government of Korea (later South Korea) imposed a wide ban on all Japanese "cultural products." Until repealed in 1998, the only way Japanese products could legally enter the South Korean market was through licensing to a third-party (non-Japanese) distributor, as was the case with the Comboy and its successor, the Super Comboy, a version of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[32]

Soviet Union/Russia

While the NES in its heyday was never officially released in the Soviet Union, an unlicensed Chinese hardware clone named the Dendy was produced in Russia in the early 1990s. Aesthetically, it is an exact duplicate of the original Famicom, with the color scheme and labels altered. In addition, the hardwired controllers of the original console were omitted in favor of removable controllers which connected to the front of the unit using DE-9 serial connectors, identical to those used in the Atari 2600 and the Atari 8-bit family of computers.[33] All games sold in Russia for Dendy are bootleg copies, not the original Nintendo cartridges.

Leading the industry (1987–1990)

In North America, the NES widely outsold its primary competitors, the Atari 7800 and the Sega Master System. The successful launch of the NES positioned Nintendo to dominate the home video game market for the remainder of the 1980s. Buoyed by the success of the system, NES Game Paks produced similarly appropriate sales records. Released in 1988 in Japan, Super Mario Bros. 3 would gross well over US$500 million, selling over 7 million copies in America and 4 million copies in Japan, making it the most popular and fastest selling[34] standalone home video game in history. The original Super Mario Bros. actually outsold Super Mario Bros. 3 by a margin of 40.24 million to 17.28 million. Many of the sales of the original game, however, were the result of the fact that it was packaged alongside the NES console itself.

By mid-1986, 19% (6.5 million) of Japanese households owned a Famicom;[12] one third by mid-1988.[35] By 1990, 30% of American households had the NES, compared to 23% for all personal computers.[36] Its popularity greatly affected the computer-game industry, with executives stating that "Nintendo's success has destroyed the software entertainment market" and "there's been a much greater falling off of disk sales than anyone anticipated". The growth in sales of the Commodore 64 ended; Nintendo sold almost as many consoles in 1988 as the total number of 64s had been sold in five years. Trip Hawkins called Nintendo "the last hurrah of the 8-bit world".[37] By 1990, the NES had reached a larger user base in the United States than any previous console, surpassing the previous record set by the Atari 2600 in 1982.[38] In 1990 Nintendo surpassed Toyota as Japan's most successful corporation.[39]

Market decline (1990–1995)

In the late 80s, Nintendo's dominance was threatened by newer, technologically superior consoles. 1987, NEC and Hudson Soft released the PC Engine, and a year later, Sega released the 16 bit Mega Drive. Both were introduced in North America in 1989, where they were respectively marketed as the "TurboGrafx-16" and the "Genesis." Facing new competition from the PC Engine in Japan, and the Genesis in North America, Nintendo's market share began to erode. Nintendo responded in the form of the Super Famicom ("Super Nintendo Entertainment System" in North America and Europe), the Famicom's 16-bit successor, in 1990. Although Nintendo announced their intention to continue to support the Famicom alongside their newer console, the success of the newer offering began to draw even more gamers and developers from the original NES, whose decline accelerated. However, Nintendo did continue support of the NES for about three years after the September 1991 release of the Super NES, with the NES's final first-party games being Zoda's Revenge: StarTropics II and Wario's Woods.

The original Japanese Famicom hardware features an RF modulator audio/video output connector, but more Japanese television sets had dropped RF connectors in favor of higher-quality RCA composite video output by the early 1990s. A revised Famicom (HVC-101 model), often referred to unofficially as the AV Famicom, was released in Japan in 1993, largely to address this problem. It borrowed some design cues from the Super NES. The HVC-101 model replaced the original HVC-001 model's RF modulator with RCA composite cables, eliminated the hardwired controllers, and features a new, more compact case design. Retailing for ¥4,800 to ¥7,200 (equivalent to approximately $42 to $60 USD), the HVC-101 model remained in production for almost a decade before being finally discontinued in 2003.[40] The case design of the AV Famicom was adopted for a subsequent North American rerelease of the NES. The NES-101 model (sometimes referred to unofficially as the "NES 2") differs from the Japanese HVC-101 model in that it omitted the RCA composite output connectors that had been included in the original NES-001 model, and sports only RF output capabilities.[41]

After a full decade of production, the NES was formally discontinued in the U.S. in 1995.[31] By the end of its run, over 60 million NES units had been sold throughout the world.[42]

Discontinuation and emulation (1995–present)

The NES's market presence declined from 1991 to 1995, with the Sega Genesis and Nintendo's own Super NES gaining market share, with next-generation CD-ROM-based systems forthcoming. Even though the NES was discontinued in North America in 1995, many millions of cartridges for the system existed. The secondhand market of video rental stores, thrift stores, yard sales, flea markets, and games repackaged by Game Time Inc. / Game Trader Inc. and sold at retail stores such as K-Mart, was burgeoning. Many people began to rediscover the NES around this time, and by 1997, many older NES games were becoming popular with collectors.

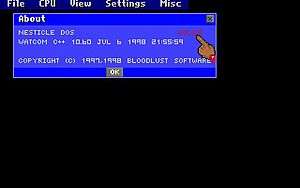

At the same time, computer programmers began to develop emulators capable of reproducing the internal workings of the NES on modern personal computers. When paired with a ROM image (a bit-for-bit copy of a NES cartridge's program code), the games can be played on a computer. Emulators also come with a variety of built-in functions that change the gaming experience, such as save states which allow the player to save and resume progress at an exact spot in the game.

Nintendo did not respond positively to these developments and became one of the most vocal opponents of ROM image trading. Nintendo and its supporters claim that such trading represents blatant software piracy.[43] Proponents of ROM image trading argue that emulation preserves many classic games for future generations, outside of their more fragile cartridge formats.[44]

In 2005, Nintendo announced plans to make classic NES titles available on the Virtual Console download service for the Wii console, which is based on their own emulation technology. Initial titles released included Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda and Donkey Kong,[45] with blockbuster titles such as Super Mario Bros., Punch-Out!! and Metroid appearing in the following months.[46]

In 2007, Nintendo Co., Ltd. announced that it would no longer repair Famicom systems, due to an increasing shortage of the necessary parts.[47]

See also

References

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 15, 2003). "Building the Ultimate Game Machine". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 7. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004.

- 1 2 Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "History of the Nintendo Entertainment System or Famicom". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ "Gaming for 5 to 95". Nintendo Co Ltd. March 31, 2003. 82-2544. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 15, 2003). "Codename: Famicom". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 7. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004.

- ↑ Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "The Famicom rules the world! – (1983–89)". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goldberg, Marty (October 18, 2005). "Nintendo Entertainment System 20th Anniversary". ClassicGaming.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ "Obituary: Gaming pioneer Steve Bristow helped design Tank, Breakout". Ars Technica. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ Teiser, Don (June 14, 1983). "Interoffice Memo". Retrieved February 12, 2006 – via Atari History Museum.

- ↑ "The NES turns 30: How it began, worked, and saved an industry". Ars Technica. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 15, 2003). "Coming to America". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 11. Archived from the original on July 1, 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 Nielsen, Martin (August 19, 2005). "The Nintendo Entertainment System". NES World. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Takiff, Jonathan (June 20, 1986). "Video Games Gain In Japan, Are Due For Assault On U.S.". The Vindicator. p. 2. Retrieved 10 April 2012 – via Google News Archive.

- 1 2 3 Jeremiah Black (director), Jeff Rubin, Josh Shabtai, Dan Ackerman, Libe Goad, Shandi Sullivan, T. J. Allard (July 13, 2007). Play Value: The Rise of Nintendo (podcast). ON Networks. Archived from the original (Flash Video) on February 22, 2011. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The Game System That Almost Wasn't". Nintendo Power Source. Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on October 12, 1997. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Beschizza, Rob (November 2, 2007). "Retro: Nintendo's 1985 Wireless-Equipped Gaming PC". Gadget Lab. Wired. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 2003). "Uphill Struggle". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ↑ Bloom, Steve, ed. (March 1985). "Nintendo's Final Solution". Hotline. Electronic Games. Reese Communications. 4 (36): 9. ISSN 0730-6687. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ↑ Wilson, Johnny L. (November 1991). "A History of Computer Games" (Portable Document Format). Computer Gaming World. Anaheim Hills, California: Golden Empire Publications (88): 22, 24. ISSN 0744-6667. Retrieved November 18, 2013 – via Computer Gaming World Museum.

- 1 2 Steve Lin [stevenplin] (31 October 2015). "Nintendo funded research in Jan/Feb 1986 showed the main reason kids wanted an NES was ROB & 90% sell through in NYC" (Tweet). Retrieved 2 November 2015 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Hill, Charles W. L.; Jones, Gareth R. (2006). Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach. Houghton Mifflin. p. 127. ISBN 0-13-102009-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, Lucas M. (January 16, 2007). "Baseball VC Review". IGN. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ "The first to move video action off the screen.". New York Magazine. 18 (43). November 4, 1985. p. 9.

- ↑ Turner, Benjamin; Nutt, Christian (July 2003). "Big Apple, Little N". Nintendo Famicom: 20 Years of Fun!. GameSpy. p. 13. Archived from the original on August 5, 2004. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Smith, Steve (June 23, 1986). "Atari, Sega, and Nintendo Plan Comeback for Video Games". HFN: The Weekly Home Furnishings Newspaper. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via The Nintendo Classic Archive.

- 1 2 3 Pollack, Andrew (September 27, 1986). "Video Games, Once Zapped, In Comeback". The New York Times. A1. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Vidgame.net: Nintendo Entertainment System NES Toaser". Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Zap! Video Games Make A Comeback". Peach Section. The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Scripps Howard News Service. February 28, 1987. P-3. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ↑ Dvorchak, Robert (July 30, 1989). "NEC out to dazzle Nintendo fans". Business. Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. The Associated Press. 1D. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ↑ Belson, Eve (December 1988). "America's Toy Box". Features. Orange Coast. Costa Mesa, California: Emmis Communications. 14 (12): 87–88, 90. ISSN 0279-0483. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "PAL releases". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- 1 2 Nielsen, Martin (October 8, 1997). "The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) FAQ v3.0A". Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2005 – via ClassicGaming.com's Museum.

- ↑ Japan Echo Inc., eds. (7 December 1998). "Breaking the Ice". Trends in Japan. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- ↑ "Dendy". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Rick (August 2002). "Super Mario Sales Data: Historical Units Sold Numbers for Mario Bros on NES, SNES, N64...". GameCubicle.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ Keiser, Gregg (June 1998). "One Million Sold in One Day". News & Notes. Compute!. New York City: COMPUTE! Publications. 10: 7. ISSN 0194-357X. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Fusion, Transfusion or Confusion: Future Directions In Computer Entertainment" (Portable Document Format). News & Notes. Computer Gaming World. Anaheim Hills, California: Golden Empire Publications (77): 26, 28. December 1990. ISSN 0744-6667. Retrieved November 10, 2013 – via Computer Gaming World Museum.

- ↑ Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Features. Compute!. New York City: COMPUTE! Publications. 11: 28–33. ISSN 0194-357X. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ↑ GaZZwa. "History of games (part 2)". Gaming World. Archived from the original on November 3, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ Liedholm, Marcus; Liedholm, Mattias. "A new era – (1990–97)". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ "AV Family Computer". |tsr's NES archive. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ "Nintendo Entertainment System 2". Vidgame.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- ↑ "| Nintendo - Corporate Information | Company History". Nintendo.com. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ↑ "| Nintendo - Corporate Information | Legal Information (Copyrights, Emulators, ROMs, etc.)". Nintendo.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ Pettus, Sam (10 March 2000), "Module One: The Emulator | Part 1 - The Basis for Emulation", Emulation: Right or Wrong? (Final ed.), retrieved November 2, 2015 – via World of Spectrum

- ↑ "IGN: Wii: 62 Games in First Five Weeks". IGN Wii. Retrieved November 3, 2006.

- ↑ "Nintendo: Virtual Console". Nintendo. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Nintendo's classic Famicom faces end of road". AFP. October 31, 2007. Archived from the original on November 5, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.