Impacted wisdom teeth

| Impacted wisdom teeth | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 3D CT of an impacted wisdom tooth adjacent the inferior alveolar nerve prior to removal of wisdom tooth | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | dentistry |

| ICD-10 | K01.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 520.6 |

| OMIM | 189490 |

| DiseasesDB | 32003 |

| MedlinePlus | 001057 |

| MeSH | C07.793.846 |

Impacted wisdom teeth (or impacted third molars) are wisdom teeth which do not fully erupt into the mouth because of blockage from other teeth (impaction). If the wisdom teeth do not have an open connection to the mouth, pain can develop with the onset of inflammation or infection or damage to the adjacent teeth. Common accepted hypothesis that determine eruption is the angle at which the 3rd molars sit, the stage of root formation of 3rd molars at the point of screening, depth of impaction, how much room there is for eruption as well as the size of the 3rd molar.[1]

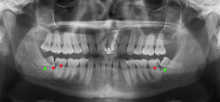

Wisdom teeth likely become impacted because of a mismatch between the size of the teeth and the size of the jaw. Impacted wisdom teeth are classified by their direction of impaction, their depth compared to the biting surface of adjacent teeth and the amount of the tooth's crown that extends through gum tissue or bone. Impacted wisdom teeth can also be classified by the presence or absence of symptoms and disease. Screening for the presence of wisdom teeth often begins in late adolescence when a partially developed tooth may become impacted. Screening commonly includes clinical examination as well as x-rays such as panoramic radiographs.

Infection resulting from impacted wisdom teeth can be initially treated with antibiotics, local debridement or soft tissue surgery of the gum tissue overlying the tooth. Over time, most of these treatments tend to fail and patients develop recurrent symptoms. The most common treatment is wisdom tooth removal. The risks of wisdom tooth removal are roughly proportional to the difficulty of the extraction. Sometimes, when there is a high risk to the inferior alveolar nerve, only the crown of the tooth will be removed (intentionally leaving the roots) in a procedure called a coronectomy. The long-term risk of coronectomy is that chronic infection can persist from the tooth remnants. The prognosis for the second molar is good following the wisdom teeth removal with the likelihood of bone loss after surgery increased when the extractions are completed in people who are 25 years of age or older. A treatment controversy exists about the need for and timing of the removal of disease-free impacted wisdom teeth that are not causing problems. Supporters of early removal cite the increasing risks for extraction over time and the costs of monitoring the wisdom teeth that are not removed. Supporters for retaining wisdom teeth cite the risk and cost of unnecessary surgery.

This condition affects up to 72% of the Swedish population.[2] Wisdom teeth have been described in the ancient texts of Plato and Hippocrates, the works of Darwin and in the earliest manuals of operative dentistry. It was the meeting of sterile technique, radiology and anaesthesia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that allowed the more routine management of impacted wisdom teeth.

Classification

All teeth are classified as either developing, erupted (into the mouth), embedded (failure to erupt despite lack of blockage from another tooth) or impacted. An impacted tooth is one that fails to erupt due to blockage from another tooth.

Wisdom teeth develop between the ages of 14 and 25, with 50% of root formation completed by age 16 and 95% of all teeth erupted by the age of 25. However, tooth movement can continue beyond the age of 25.[3]:140

Impacted wisdom teeth are classified by the direction and depth of impaction, the amount of available space for tooth eruption. and the amount soft tissue or bone (or both) that covers them. The classification structure helps clinicians estimate the risks for impaction, infections and complications associated with wisdom teeth removal.[4] Wisdom teeth are also classified by the presence (or absence) of symptoms and disease.[5]

One review found that 11% of teeth will have evidence of disease and are symptomatic, 0.6% will be symptomatic but have no disease, 51% will be asymptomatic but have disease present and 37% will be asymptomatic and have no disease.[5]

Impacted wisdom teeth are often described by the direction of their impaction (forward tilting, or mesioangular being the most common), the depth of impaction and the age of the patient as well as other factors such as pre-existing infection or the presence of pathology.[3]:143–144 Of these predictors, age correlates best with extraction difficulty and complications during wisdom teeth removal[6] rather than the orientation of the impaction.[7]

Another classification system often taught in U.S. dental schools is known as Pell and Gregory Classification. This system includes a horizontal and vertical component to classify the location of third molars (predominately applicable to mandibular third molars): the third molar's relationship to the occlusal plane being the vertical or x-component and to the anterior border of the ramus being the horizontal or y-component. Vertically, Class A impaction is one in which the occlusal surface of the impacted tooth is level or nearly level with the occlusal plane and the cervical line of the adjacent second molar.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Impacted wisdom teeth without a communication to the mouth, that have no pathology associated with the tooth and have not caused tooth resorption on the blocking tooth rarely have symptoms. In fact, only 12% of impacted wisdom teeth are associated with pathology.[9]

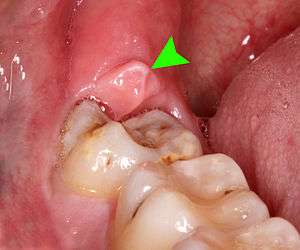

When wisdom teeth communicate with the mouth, the most common symptom is localized pain, swelling and bleeding of the tissue overlying the tooth. This tissue is called the operculum and the disorder called pericoronitis which means inflammation around the crown of the tooth.[3]:141 Low grade chronic periodontitis commonly occurs on either the wisdom tooth or the second molar, causing less obvious symptoms such as bad breath and bleeding from the gums. The teeth can also remain asymptomatic (pain free), even with disease.[5] As the teeth near the mouth during normal development, people sometimes report mild pressure of other symptoms similar to teething.

The term asymptomatic means that the person has no symptoms. The term asymptomatic should not be equated with absence of disease. Most diseases have no symptoms early in the disease process. A pain free or asymptomatic tooth can still be infected for many years before pain symptoms develop.[5]

Causes

Wisdom teeth become impacted when there is not enough room in the jaws to allow for all of the teeth to erupt into the mouth. Because the wisdom teeth are the last to erupt, due to insufficient room in the jaws to accommodate more teeth, the wisdom teeth become stuck in the jaws, i.e., impacted. There is a genetic predisposition to tooth impaction. Genetics plays an important, albeit unpredictable role in dictating jaw and tooth size and tooth eruption potential of the teeth. Some also believe that there is a devolutionary decrease in jaw size due to softer modern diets that are more refined and less coarse than our ancestors'.[4]

Pathophysiology

Impactions completely covered by bone and soft tissue have a low rate of clinically significant pathology – generally small cysts or uncommon tumors that form from the residual epithelial remnants around the crowns of the teeth.

Estimates of the incidence of cysts or other neoplasms (almost all benign) around impacted teeth average at 3%, usually seen in people under the age of 40. This suggests that the chance of tumor formation decreases with age.[3]:141

For partially impacted teeth in those over 20 year of age, the most common pathology seen, and the most common reason for wisdom teeth removal, is pericoronitis or infection of the gum tissue over the impacted tooth. The bacteria associated with infections include Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Bacteroides bacteria. The next most common pathology seen is cavities or tooth decay. Fifteen percent of people with retained wisdom teeth exposed to the mouth have cavities on the wisdom tooth or adjacent second molar due to a wisdom tooth. The rate of cavities on the back of the second molar has been reported anywhere from 1% to 19% with the wide variation attributed to increased age.[10]

In five percent of cases, advanced periodontitis or gum inflammation between the second and third molars precipitates the removal of wisdom teeth.[3]:141[4] Among patients with retained, asymptomatic wisdom teeth, roughly 25% have gum infections (periodontal disease).[11]:ch13 Teeth with periodontal pockets of greater than 5mm have tooth loss rates that start at 10 teeth lost per 1000 teeth per year at 5mm to a rate of 70 teeth lost per year per 1000 teeth at 11mm.[12]:57 The risk of periodontal disease and caries on third molars increases with age with a small minority (less than 2%) of adults age 65 years or older maintaining the teeth without caries or periodontal disease and 13% maintaining unimpacted wisdom teeth without caries or periodontal disease.[13] Periodontal probing depths increase over time to greater than 4 mm in a significant proportion of young adults with retained impacted wisdom teeth which is associated with increases in serum inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and C-reactive protein.[14]

Crowding of the front teeth is not believed to be caused by the eruption of wisdom teeth although this is a reason many dental clinicians use to justify wisdom teeth extraction.[3]:141,[15]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of impaction can be made clinically if enough of the wisdom tooth is visible to determine its angulation, depth, and if the patient is old enough that further eruption or uprighting is unlikely. Wisdom teeth continue to move into adulthood (20–30 years old) due to eruption and then continue some later movement owing to periodontal disease.[16]

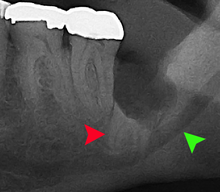

If the tooth cannot be assessed with clinical exam alone, the diagnosis is made using either a panoramic radiograph or cone-beam CT. Where unerupted wisdom teeth still have eruption potential several predictors are used to determine the chance of the teeth becoming impacted. The ratio of space between the tooth crown length and the amount of space available, the angle of the teeth compared to the other teeth are the two most commonly used predictors, with the space ratio being the most accurate. Despite the capacity for movement into early adulthood, the likelihood that the tooth will become impacted can be predicted when the ratio of space available to the length of the crown of the tooth is under 1.[3]:141

Screening

There is no standard to screen for wisdom teeth. It has been suggested, absent evidence to support routinely retaining or removing wisdom teeth, that evaluation with panoramic radiograph, starting between the ages of 16 and 25 be completed every 3 years. Once there is the possibility of the teeth developing disease, then a discussion about the operative risks versus long-term risk of retention with an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or other clinician trained to evaluate wisdom teeth is recommended. These recommendations are based on expert opinion level evidence.[17] Screening at a younger age may be required if the second molars (the "12-year molars") fail to erupt as ectopic positioning of the wisdom teeth can prevent their eruption. Radiographs can be avoided if the majority of the tooth is visible in the mouth.

Treatment

Wisdom teeth that are fully erupted and in normal function need no special attention and should be treated just like any other tooth. It is more challenging, however to make treatment decisions with asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom teeth, i.e. wisdom teeth that have no communication to the mouth and no evidence of clinical or radiographic disease (see Treatment controversy below).[2]

Local treatment

Where there is an operculum of gingiva overlying the tooth that has become infected it can be treated with local cleaning, an antiseptic rinse of the area and antibiotics if severe. Definitive treatment can be excision of the tissue, however, recurrence of these infections is high. Pericoronitis, while a small area of tissue, should be viewed with caution, because it lies near the anatomic planes of the neck and can progress to life-threatening neck infections.[12]:440–441

Wisdom teeth removal

Wisdom teeth removal (extraction) is the most common treatment for impacted wisdom teeth. In the US, 10 million wisdom teeth are removed annually.[18] The general agreement for wisdom tooth removal is the presence of disease or symptoms related to that tooth.

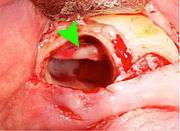

The procedure, depending on the depth of the impaction and angle of the tooth, is to create an incision in the mucosa of the mouth, remove bone of the mandible or maxilla adjacent the tooth, section the tooth and extract it in pieces. This can be completed under local anaesthetic, sedation or general anaesthetic.

Recovery, risks and complications

Most patients will experience pain and swelling (worst on the first post-operative day) then return to work after 2 to 3 days with the rate of discomfort decreased to about 25% by post-operative day 7 unless affected by dry socket: a disorder of wound healing that prolongs post-operative pain. It can be 4 to 6 weeks before patients are fully recovered with a full range of jaw movements.[19] A Cochrane investigation found that the use of antibiotics either just before or just after surgery reduced the risk of infection, pain and dry socket after wisdom teeth are removed by oral surgeons, but that using antibiotics also causes more side effects for these patients. Twelve patients needed to receive antibiotics to prevent 1 infection and for every 21 people who received antibiotics, an adverse event was likely. The conclusion of the review was that antibiotics given to healthy people to prevent infections, may cause more harm than benefit to both the individual patients and the population as a whole.[20] Another Cochrane Investigation has found post-operative pain is effectively managed with either ibuprofen, or ibuprofen in combination with acetaminophen.[21]

Long-term complications can include periodontal complications such as bone loss on the second molar following wisdom teeth removal. Bone loss as a complication after wisdom teeth removal is uncommon in the young but present in 43% of those of 25 years of age or older. Initiation or worsening of temporomandibular joint problems is uncommon and unpredictable. Injury to the inferior alveolar nerve resulting in numbness or partial numbness of the lower lip and chin has reported rates that vary widely from 0.04% to 5%. The largest study is from a survey of 535 oral and maxillofacial surgeons in California, where a rate of 1:2,500 was reported. The large variation in report rates is attributed to variations in technique, the patient pool and surgeon experience. Other complications that are uncommon have been reported including persistent sinus communication, damage to adjacent teeth, lingual nerve injury, displaced teeth, osteomyelitis and jaw fracture.[19] Alveolar osteitis, post-operative infection, excessive bleeding may also be expected.[22]

Treatment controversy

Many impacted wisdom teeth are extracted prior to the age of 25, when full eruption can be reasonably expected and before symptoms or disease have begun. This has led to a treatment controversy generally referred to as the extraction of asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom teeth.

In 2000, the first National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) of the United Kingdom set guidelines[23] to limit the removal of asymptomatic disease-free third molars citing the number of pathology free impacted teeth being removed and the potential cost savings to the public purse. Advocates of the policy point out that the impacted wisdom teeth can be monitored and avoidance of surgery also means avoidance of the recovery, risks, complications and costs associated with it. Following implementation of the NICE guidelines the UK saw a decrease in the number of impacted third molar operations between 2000 and 2006 and a rise in the average age at extraction from 25 to 31 years.[10] American Public Health Association has adopted a similar policy against removal of third molars before any problems have occurred.[24]

Those who argue against a blanket moratorium on the extraction of asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom teeth point out that wisdom teeth commonly develop periodontal disease or cavities which may eventually damage the second molars and that there are costs associated with monitoring wisdom teeth. They also point to the fact that there is an increase in the rate of post-operative periodontal disease on the second molar,[5] difficulty of surgery and post-operative recovery time with age.[6] The UK has also seen an increase in the rate of dental caries on the lower second molars increasing from 4–5% prior to the NICE guideline to 19% after its adoption.[10]

Although most studies arrive at the conclusion of negative long-term outcomes e.g. increased pocketing & attachment loss after surgery, it is clear that early removal (before 25 years old), good post-operative hygiene & plaque control, and lack of pre-existing periodontal pathology before surgery are the most crucial factors that minimise the probability of adverse post-surgical outcomes.[25]

The Cochrane review of surgical removal versus retention of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth suggests that the presence of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth may be associated with increased risk of periodontal disease affecting adjacent 2nd molar (measured by distal probing depth > 4 mm on that tooth) in the long term, however it is of very low quality evidence and high risk of bias. Another study which was at high risk of bias, found no evidence to suggest that removal of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth has an effect on crowding in the dental arch. There is also insufficient evidence to highlight a difference in risk of decay with or without impacted wisdom tooth.[22]

One trial in adolescents who had orthodontic treatment comparing the removal of impacted mandibular wisdom teeth with retention was identified. It only examined the effect on late lower incisor crowding and was rated 'highly biased' by the authors. The authors concluded that there is not enough evidence to support either the routine removal or retention of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth.[15] Another randomised controlled trial done in the UK has suggested that it is not reasonable to remove asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom tooth merely to prevent incisor crowding as there is not strong enough evidence to show this association.[26]

Due to the lack of sufficient evidence to determine whether such teeth should be removed or not, the patient's preference and values should be taken into account with clinical expertise exercised and careful consideration of risks & benefits to determine treatment.[25] If it is decided to retain asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth, clinical assessment at regular intervals is advisable to prevent undesirable outcomes (pericoronitis, root resorption, cyst formation, tumour formation, inflammation/infection).[22]

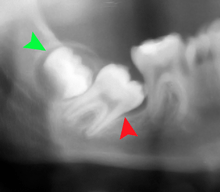

Coronectomy

Coronectomy is a procedure used when the surgeon believes that there is a high risk of inferior alveolar nerve injury. After making the incision in the mucosa and removing bone adjacent the tooth, the crown is cut and removed with no attempt at removing the roots. It is indicated when there is no disease of the dental pulp or infection around the crown of the tooth and there is a high risk of inferior alveolar nerve injury.

Coronectomy, while lessening the immediate risk to the inferior alveolar nerve function has its own complication rates and can result in repeated surgeries. Between 2.3% and 38.3% of roots loosen during the procedure and need to be removed and up to 4.9% of cases require reoperation due to persistent pain, root exposure or persistent infection. The roots have also been reported to migrate in 13.2% to 85.9% of cases.[27]

Prognosis

The prognosis for impacted wisdom teeth depends on the depth of the impaction. When they lack a communication to the mouth, the main risk is the chance of cyst or neoplasm formation which is relatively uncommon.

Once communicating with the mouth, the onset of disease or symptoms cannot be predicted but the chance of it does increase with age. Less than 2% of wisdom teeth are free of either periodontal disease or caries by age 65.[13] Further, several studies have found that between 30% – 60% of people with previously asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth will have them extracted due to symptoms or disease, 4–12 years after initial examination.[2]

Extraction of the wisdom teeth removes the disease on the wisdom tooth itself and also appears to improve the periodontal status of the second molar, although this benefit diminishes beyond the age of 25.[13]

Epidemiology

Few studies have looked at the percentage of the time wisdom teeth are present or the rate of wisdom teeth eruption. The lack of up to five teeth (excluding third molars, i.e. wisdom teeth) is termed hypodontia. Missing third molars occur in 9-30% of studied populations.

One large scale study on a group of young adults in New Zealand showed 95.6% had at least 1 wisdom tooth with an eruption rate of 15% in the maxilla and 20% in the mandible.[28] Another study on 5000 army recruits found 10,767 impacted wisdom teeth.[29]:246 The frequency of impacted lower third molars has been found to be 72%[2] and the frequency of retained impacted wisdom teeth that are free of disease and symptoms is estimated at 11.6% to 29% which drops with age.[28]

The incidence of wisdom tooth removal was estimated to be 4 per 1000 person years in England and Wales prior to the 2000 NICE guidelines.[2]

History

Wisdom teeth have been described in the ancient texts of Plato and Hippocrates. "Teeth of wisdom" being from the Latin, dentes sapientiæ, which in turn is derived from the Hippocratic term, sophronisteres, from the Greek sophron, meaning prudent.[30]

Charles Darwin believed the wisdom teeth to be in decline with evolution which his contemporary, Paolo Mantegazza, later proved to be false when he discovered Darwin was not opening the jawbones of specimens to find the impacted tooth stuck in the jaw.[31]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the collision of sterile technique, anaesthesia and radiology made routine surgery on the wisdom teeth possible. John Tomes's 1873 text A System of Dental Surgery describes techniques for removal of "third molars, or dentes sapientiæ" including descriptions of inferior alveolar nerve injury, jaw fracture and pupil dilation after opium is placed in the socket.[32] Other texts from about this time speculate on their deevolution, that they are prone to decay and discussion on whether or not they lead to crowding of the other teeth.[33]

References

- ↑ "Third Molar Surgery: A Review Of Current Controversies In Prophylactic Removal Of Wisdom Teeth - Oral Health Group". Oral Health Group. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodson TB, Susarta SM (Apr 2010). "Impacted wisdom teeth (systematic review)". Clin Evid (Online). 2010 (1302). PMC 2907590

. PMID 21729337.

. PMID 21729337. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peterson, Larry J.; Miloro, Michael (2004). Peterson's Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (2nd ed.). PMPH-USA. ISBN 978-1-55009-234-9.

- 1 2 3 Juodzbalys G, Daugela P (Apr–Jun 2013). "Mandibular Third Molar Impaction: Review of Literature and a Proposal of a Classification (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Res. 4 (2): e1. doi:10.5037/jomr.2013.4201. PMC 3886113

. PMID 24422029.

. PMID 24422029. - 1 2 3 4 5 Dodson TB (Sep 2012). "The management of the asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom tooth: removal versus retention. (review)". Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 20 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.005. PMID 23021394.

- 1 2 Pogrel MA (2012). "What Is the Effect of Timing of Removal on the Incidence and Severity of Complications (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 37–40.

- ↑ Bali A, Bali D, Sharma A, Verma G (Sep 2013). "Is Pederson Index a True Predictive Difficulty Index for Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Surgery? A Meta-analysis.". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 12 (3): 359–364. doi:10.1007/s12663-012-0435-x.

- ↑ Hupp, James R., et. al. Contemporary Maxillofacial Surgery, 6E, Elsevier-Mosby, 2014. ISBN 978-0-323-09177-0

- ↑ Friedman, JW (September 2007). "The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard.". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (9): 1554–9. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.100271. PMC 1963310

. PMID 17666691.

. PMID 17666691. - 1 2 3 Renton T, Al-Haboubi M, Pau A, Shepherd J, Gallagher JE (2012). "What Has Been the United Kingdom's Experience with Retention of Third Molars?". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 48–57.

- ↑ Bell RB, Khan HA (2012). Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2527-6.

- 1 2 Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA (2012). Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- 1 2 3 Marciani RD (2012). "Is there pathology associated with asymptomatic third molars (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 15–19. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.025.

- ↑ Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Moss KL, et al. (2012). "What Are the Local and Systemic Implications of Third Molar Retention". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 58–65.

- 1 2 Mettes TD (Jun 2012). "Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. (Cochrane Invest)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 13 (6): CD003879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub3. PMID 22696337.

- ↑ Phillips C, White RP (2012). "How Predictable Is the Position of Third (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 11–14.

- ↑ Dodson TB (2012). "Surveillance as a Management Strategy for Retained Third Molars: Is it Desirable?". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 20–24. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.026. PMID 22916696.

- ↑ Moisse, Katie (15 December 2011). "Parents Sue After Teen Dies During Wisdom Tooth Surgery". ABC News. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- 1 2 Pogrel MA (2012). "What are the Risks of Operative Intervention (review)". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 33–36.

- ↑ Lodi G, Figini L, et al. (Nov 2012). "Antibiotics to prevent complications following tooth extractions". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (11): CD003811. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003811.pub2. PMID 23152221.

- ↑ Bailey E, Worthington HV, et al. (Dec 2013). "Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: 12:CD004624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004624.pub2.

- 1 2 3 Ghaeminia, Hossein; Perry, John; Nienhuijs, Marloes EL; Toedtling, Verena; Tummers, Marcia; Hoppenreijs, Theo JM; Van der Sanden, Wil JM; Mettes, Theodorus G (2016-08-31). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003879.pub4. ISSN 1465-1858.

- ↑ TA1 Wisdom teeth – removal: guidance. London, United Kingdom: National Institute for Clinical Excellence (UK). 2000.

- ↑ "Opposition to Prophylactic Removal of Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth)". Policy Statement Database. American Public Health Association. 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- 1 2 Dodson, Thomas B. Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. pp. 122–126.

- ↑ Song, F.; O'Meara, S.; Wilson, P.; Golder, S.; Kleijnen, J. (2000-01-01). "The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth". Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 4 (15): 1–55. ISSN 1366-5278. PMID 10932022.

- ↑ Ghaeminia H (2013). "Coronectomy may be a way of managing impacted third molars (systematic review)". Evid Based Dent. 14 (2): 57–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400939. PMID 23792405.

- 1 2 Dodson TB (2012). "How Many Patients Have Third Molars and How Many Have One or More Asymptomatic, Disease-Free Third Molars?". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 70 (Suppl 1): 4–7. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.038.

- ↑ Fonseca RJ (2000). Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Volume 1. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-9632-5.

- ↑ Mitchell E, Barclay J (1819). A Series of Engravings: Representing the Bones of the Human Skeleton; with the Skeletons of Some of the Lower Animals. High Street, London, UK: Oliver & Boyd.

- ↑ Mantegazza, P (June 1878). "Concerning the Atrophy and Absence of Wisdom Teeth". In Stevenson, RK. Anthropology Society of Paris Meeting of June 20, 1878. Paris, France: Anthropology Society of Paris. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Tomes, J.; Tomes, C. S. (1873). A System of Dental Surgery. London, UK: J&A Churchill.

- ↑ Gant, F (1878). Science and Practice of Surgery ; Including Special Chapters by Different Authors, Volume 2. Philadelphia, USA: Lindsay & Blakiston. p. 308.