Impeachment in the United States

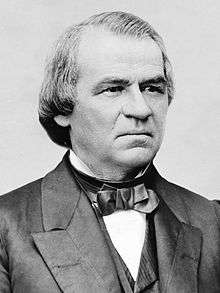

Impeachment in the United States is an enumerated power of the legislature that allows formal charges to be brought against a civil officer of government for crimes alleged to have been committed. Most impeachments have concerned alleged crimes committed while in office, though there have been a few cases in which Congress has impeached and convicted officials partly for prior crimes.[1] The actual trial on such charges, and subsequent removal of an official upon conviction, is separate from the act of impeachment itself. Impeachment proceedings have been initiated against several presidents of the United States. Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton are the only two presidents to have been successfully impeached by the House of Representatives, and both were later acquitted by the Senate. The impeachment process of Richard Nixon was technically unsuccessful, as Nixon resigned his office before the vote of the full House for impeachment, but successful in the broader sense of leading to Nixon's departure. To date, no U.S. President has been removed from office by impeachment and conviction.

Impeachment is analogous to indictment in regular court proceedings; trial by the other house is analogous to the trial before judge and jury in regular courts. Typically, the lower house of the legislature impeaches the official and the upper house conducts the trial.

At the federal level, Article II of the United States Constitution states in Section 4 that "The President, Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors." The House of Representatives has the sole power of impeaching, while the United States Senate has the sole power to try all impeachments. The removal of impeached officials is automatic upon conviction in the Senate. In Nixon v. United States (1993), the Supreme Court determined that the federal judiciary cannot review such proceedings.

Impeachment can also occur at the state level: state legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors, in accordance with their respective state constitutions.

At the Philadelphia Convention, Benjamin Franklin noted that, historically, the removal of "obnoxious" chief executives had been accomplished by assassination. Franklin suggested that a proceduralized mechanism for removal—impeachment—would be preferable.[2]

Federal impeachment

House of Representatives

Impeachment proceedings may be commenced by a member of the House of Representatives on her or his own initiative, either by presenting a list of the charges under oath, or by asking for referral to the appropriate committee. The impeachment process may be initiated by non-members. For example, when the Judicial Conference of the United States suggests a federal judge be impeached, a charge of actions constituting grounds for impeachment may come from a special prosecutor, the President, or state or territorial legislature, grand jury, or by petition.

The type of impeachment resolution determines the committee to which it is referred. A resolution impeaching a particular individual is typically referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. A resolution to authorize an investigation regarding impeachable conduct is referred to the House Committee on Rules, and then to the Judiciary Committee. The House Committee on the Judiciary, by majority vote, will determine whether grounds for impeachment exist. If the Committee finds grounds for impeachment they will set forth specific allegations of misconduct in one or more articles of impeachment. The Impeachment Resolution, or Article(s) of Impeachment, are then reported to the full House with the committee's recommendations.

The House debates the resolution and may at the conclusion consider the resolution as a whole or vote on each article of impeachment individually. A simple majority of those present and voting is required for each article or the resolution as a whole to pass. If the House votes to impeach, managers (typically referred to as "House managers", with a "lead House manager") are selected to present the case to the Senate. Recently, managers have been selected by resolution, while historically the House would occasionally elect the managers or pass a resolution allowing the appointment of managers at the discretion of the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. These managers are roughly the equivalent of the prosecution/district attorney in a standard criminal trial.

Also, the House will adopt a resolution in order to notify the Senate of its action. After receiving the notice, the Senate will adopt an order notifying the House that it is ready to receive the managers. The House managers then appear before the bar of the Senate and exhibit the articles of impeachment. After the reading of the charges, the managers return and make a verbal report to the House.

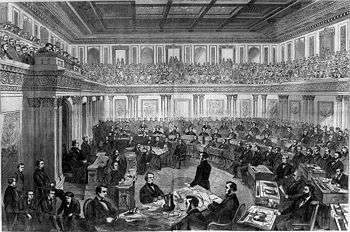

Senate

The proceedings unfold in the form of a trial, with each side having the right to call witnesses and perform cross-examinations. The House members, who are given the collective title of managers during the course of the trial, present the prosecution case and the impeached official has the right to mount a defense with his own attorneys as well. Senators must also take an oath or affirmation that they will perform their duties honestly and with due diligence (as opposed to the House of Lords in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, who vote upon their honor). After hearing the charges, the Senate usually deliberates in private. The U.S. Constitution requires a two-thirds majority for conviction.

The Senate enters judgment on its decision, whether that be to convict or acquit, and a copy of the judgment is filed with the Secretary of State.[3] Upon conviction, the official is automatically removed from office and may also be barred from holding future office. The removed official is also liable to criminal prosecution. The President may not grant a pardon in the impeachment case, but may in any resulting criminal case.

Beginning in the 1980s with Harry E. Claiborne, the Senate began using "Impeachment Trial Committees" pursuant to Senate Rule XI.[4] These committees presided over the evidentiary phase of the trials, hearing the evidence and supervising the examination and cross-examination of witnesses. The committees would then compile the evidentiary record and present it to the Senate; all senators would then have the opportunity to review the evidence before the chamber voted to convict or acquit. The purpose of the committees was to streamline impeachment trials, which otherwise would have taken up a great deal of the chamber's time. Defendants challenged the use of these committees, claiming them to be a violation of their fair trial rights as well as the Senate's constitutional mandate, as a body, to have "sole power to try all impeachments." Several impeached judges sought court intervention in their impeachment proceedings on these grounds, but the courts refused to become involved due to the Constitution's granting of impeachment and removal power solely to the legislative branch, making it a political question.

History

In the United Kingdom, impeachment was a procedure whereby a member of the House of Commons could accuse someone of a crime. If the Commons voted for the impeachment, a trial would then be held in the House of Lords. Unlike a bill of attainder, a law declaring a person guilty of a crime, impeachments did not require royal assent, so they could be used to remove troublesome officers of the Crown even if the king was trying to protect them.

The king himself, however, was above the law and could not be impeached, or indeed judged guilty of any crime. When King Charles I was tried before the Rump Parliament of the New Model Army in 1649 he denied that they had any right to legally indict him, their king, whose power was given by God and the laws of the country, saying: "no earthly power can justly call me (who is your King) in question as a delinquent … no learned lawyer will affirm that an impeachment can lie against the King." While the House of Commons pronounced him guilty and ordered his execution anyway, the jurisdictional issue tainted the proceedings.

With this example in mind, the delegates to the Philadelphia Convention chose to include an impeachment procedure in Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution which could be applied to any government official; they explicitly mentioned the President to ensure there would be no ambiguity. Opinions differed, however, as to the reasons Congress should be able to initiate an impeachment. Initial drafts listed only treason and bribery, but George Mason favored impeachment for "maladministration" (incompetence). James Madison argued that impeachment should only be for criminal behavior, arguing that a maladministration standard would effectively mean that the President would serve at the pleasure of the Senate.[5] Thus the delegates adopted a compromise version allowing impeachment for "treason, bribery and other high crimes and misdemeanors."

The precise meaning of the phrase "high crimes and misdemeanors" is somewhat ambiguous; some scholars, such as Kevin Gutzman, argue that it can encompass even non-criminal abuses of power. Whatever its theoretical scope, however, Congress traditionally regards impeachment as a power to use only in extreme cases. The House of Representatives has actually initiated impeachment proceedings only 62 times since 1789. Two cases did not come to trial because the individuals had left office.

Actual impeachments of 19 federal officers have taken place. Of these, 15 were federal judges: thirteen district court judges, one court of appeals judge (who also sat on the Commerce Court), and one Supreme Court Associate Justice. Of the other four, two were Presidents, one was a Cabinet secretary, and one was a U.S. Senator. Of the 19 impeached officials, eight were convicted. One, former judge Alcee Hastings, was elected as a member of the United States House of Representatives after being removed from office.

The 1797 impeachment of Senator William Blount of Tennessee stalled on the grounds that the Senate lacked jurisdiction over him. Because, in a separate action unrelated to the impeachment procedure, the Senate had already expelled Blount, the lack of jurisdiction may have been either because Blount was no longer a Senator, or because Senators are not civil officers of the federal government and therefore not subject to impeachment. No other member of Congress has ever been impeached, although the Constitution does give authority to either house to expel its own members (not members of the other chamber), which each has done on occasion (see List of United States senators expelled or censured and List of United States Representatives expelled, censured, or reprimanded). Expulsion removes the individual from functioning as a representative or senator because of their misbehavior, but unlike impeachment, expulsion cannot result in barring an individual from holding future office.

Impeachment of a U.S. President

The law of presidential powers and duties is ill-defined. Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote in 1952 that there is "a poverty of really useful and unambiguous authority applicable to concrete problems of executive power as they actually present themselves."[6] Two U.S. Presidents have been impeached by the House of Representatives—Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998—both later acquitted at trials held by the Senate. While articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon were passed by the House Judiciary Committee in 1974,[7] Nixon resigned the Presidency before the impeachment resolutions could be considered by the full House.[8]

When an impeachment process involves a U.S. President, the Chief Justice of the United States is required to preside during the Senate trial.[9] In all other trials, the Vice President would preside in his capacity as President of the Senate. Some academics have suggested that due to an omission in the Constitution, the Vice President also would preside over his or her own impeachment trial,[10] but the logic of this argument has been questioned.[11]

Federal officials impeached

| # | Date of Impeachment | Accused | Office | Accusation(s) | Result[Note 1] | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | July 7, 1797 |  William Blount |

United States Senator (Tennessee) | Conspiring to assist Britain in capturing Spanish territory | Senate refused to accept impeachment of a Senator by the House of Representatives, instead expelling him from the Senate on their own authority[12][Note 2] | [13] |

| 2 | March 2, 1803 | |

Judge (District of New Hampshire) | Drunkenness and unlawful rulings | Removed on March 12, 1804[12][14] | [13][14] |

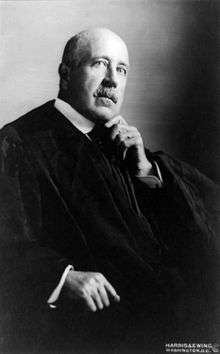

| 3 | March 12, 1804 |  Samuel Chase |

Associate Justice (Supreme Court of the United States) | Political bias and arbitrary rulings, promoting a partisan political agenda on the bench [15] | Acquitted on March 1, 1805 | [12][14] |

| 4 | April 24, 1830 |  James H. Peck |

Judge (District of Missouri) | Abuse of power[16] | Acquitted on January 31, 1831[12][14] | [13][14] |

| 5 | May 6, 1862 |  West Hughes Humphreys |

Judge (Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts of Tennessee) | Supporting the Confederacy | Removed and disqualified on June 26, 1862[13][12][14] | [13][14] |

| 6 | February 24, 1868 |  Andrew Johnson |

President of the United States | Violating the Tenure of Office Act | Acquitted on May 26, 1868[12] | [13] |

| 7 | February 28, 1873 |  Mark W. Delahay |

Judge (District of Kansas) | Drunkenness | Resigned on December 12, 1873[14][17] | [14][17] |

| 8 | March 2, 1876 |  William W. Belknap |

United States Secretary of War | Graft/corruption | Acquitted after his resignation on August 1, 1876.[12] | [13] |

| 9 | December 13, 1904 | |

Judge (Northern District of Florida) | Failure to live in his district, abuse of power[18] | Acquitted on February 27, 1905[12][14] | [13][14] |

| 10 | July 11, 1912 |  Robert Wodrow Archbald |

Associate Justice (United States Commerce Court) Judge (Third Circuit Court of Appeals) |

Improper acceptance of gifts from litigants and attorneys | Removed and disqualified on January 13, 1913[13][12][14] | [13][14] |

| 11 | April 1, 1926 |  George W. English |

Judge (Eastern District of Illinois) | Abuse of power | Resigned on November 4, 1926,[13][12] proceedings dismissed on December 13, 1926[13][14] | [13][14] |

| 12 | February 24, 1933 | |

Judge (Northern District of California) | Corruption | Acquitted on May 24, 1933[12][14] | [13][14] |

| 13 | March 2, 1936 | |

Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Champerty/corruption, tax evasion, practicing law while a judge | Removed on April 17, 1936[12][14] | [13][14] |

| 14 | July 22, 1986 |  Harry E. Claiborne |

Judge (District of Nevada) | Tax evasion | Removed on October 9, 1986[12][14] | [13][14] |

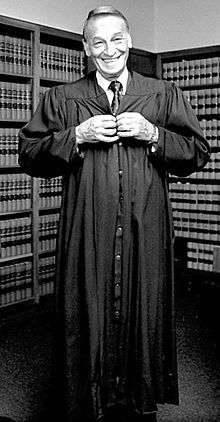

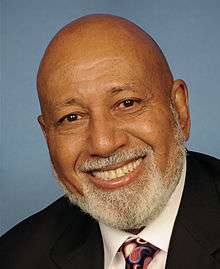

| 15 | August 3, 1988 |  Alcee Hastings |

Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Accepting a bribe, and committing perjury during the resulting investigation | Removed on October 20, 1989[12][14] | [13][14] |

| 16 | May 10, 1989 |  Walter Nixon |

Chief Judge (Southern District of Mississippi) | Perjury | Removed on November 3, 1989[12][14][Note 3] | [13][14] |

| 17 | December 19, 1998 |  Bill Clinton |

President of the United States | Perjury and obstruction of justice | Acquitted on February 12, 1999[12] | [13] |

| 18 | June 19, 2009 |  Samuel B. Kent |

Judge (Southern District of Texas) | Sexual assault, and obstruction of justice during the resulting investigation | Resigned on June 30, 2009,[14][19] proceedings dismissed on July 22, 2009[12][14][20] | [14][21] |

| 19 | March 11, 2010 |  Thomas Porteous |

Judge (Eastern District of Louisiana) | Making false financial disclosures | Removed and disqualified on December 8, 2010[12][14][22] | [14][23] |

Demands for impeachment

While the actual impeachment of a federal public official is a rare event, demands for impeachment, especially of presidents, are common,[24][25] going back to the administration of George Washington in the mid-1790s. In fact, most of the 63 resolutions mentioned above were in response to presidential actions.

While almost all of them were for the most part frivolous and were buried as soon as they were introduced, several did have their intended effect. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon[26] and Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas both resigned in response to the threat of impeachment hearings, and, most famously, President Richard Nixon resigned from office after the House Judiciary Committee had already reported articles of impeachment to the floor.

Impeachment in the states

State legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors. The court for the trial of impeachments may differ somewhat from the federal model — in New York, for instance, the Assembly (lower house) impeaches, and the State Senate tries the case, but the members of the seven-judge New York State Court of Appeals (the state's highest, constitutional court) sit with the senators as jurors as well.[27] Impeachment and removal of governors has happened occasionally throughout the history of the United States, usually for corruption charges. A total of at least eleven U.S. state governors have faced an impeachment trial; a twelfth, Governor Lee Cruce of Oklahoma, escaped impeachment conviction by a single vote in 1912. Several others, most recently Connecticut's John G. Rowland, have resigned rather than face impeachment, when events seemed to make it inevitable.[28] The most recent impeachment of a state governor occurred on January 14, 2009, when the Illinois House of Representatives voted 117-1 to impeach Rod Blagojevich on corruption charges;[29] he was subsequently removed from office and barred from holding future office by the Illinois Senate on January 29. He was the eighth U.S. state governor to be removed from office.

The procedure for impeachment, or removal, of local officials varies widely. For instance, in New York a mayor is removed directly by the governor "upon being heard" on charges — the law makes no further specification of what charges are necessary or what the governor must find in order to remove a mayor.

State and territorial officials impeached

| Date | Accused | Office | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 |  William W. Irvin |

Associate Judge, Fairfield County, Ohio Court of Common Pleas | Removed |

| 1832 |  Theophilus W. Smith |

Associate Justice, Illinois Supreme Court | Acquitted[30] |

| February 26, 1862 |  Charles L. Robinson |

Governor of Kansas | Acquitted[31] |

| February 26, 1862 | |

Secretary of State of Kansas | Removed on June 12, 1862[32] |

| February 26, 1862 | |

Kansas State auditor | Removed on June 16, 1862[32] |

| 1871 |  William Woods Holden |

Governor of North Carolina | Removed |

| 1871 |  David Butler |

Governor of Nebraska | Removed[31] |

| February 1872 |  Harrison Reed |

Governor of Florida | Acquitted[33] |

| 1872 |  Henry C. Warmoth |

Governor of Louisiana | "suspended from office," though trial was not held[34] |

| 1876 |  Adelbert Ames |

Governor of Mississippi | Resigned[31] |

| 1888 |  James W. Tate |

Kentucky State Treasurer | Removed |

| August 13, 1913[35] |  William Sulzer |

Governor of New York | Removed on October 17, 1913[36] |

| July 1917 |  James E. Ferguson |

Governor of Texas | Removed[37] |

| October 23, 1923 |  John C. Walton |

Governor of Oklahoma | Removed |

| January 21, 1929 | Henry S. Johnston |

Governor of Oklahoma | Removed |

| April 6, 1929[38] |  Huey P. Long |

Governor of Louisiana | Acquitted |

| May 1958[39] | |

Judge, Hamilton County, Tennessee Criminal Court | Removed on July 11, 1958[40] |

| March 14, 1984[41] | |

Nebraska Attorney General | Acquitted by the Nebraska Supreme Court on May 4, 1984[42] |

| February 6, 1988[43] | |

Governor of Arizona | Removed on April 4, 1988[44] |

| March 30, 1989[45] | |

West Virginia State treasurer | Resigned on July 9, 1989 before trial started[46] |

| January 25, 1991[47] | |

Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture | Resigned on February 6, 1991 before trial started[48] |

| May 24, 1994[49] | |

Associate Justice, Pennsylvania Supreme Court | Removed on October 4, 1994, and declared ineligible to hold public office in Pennsylvania[50] |

| October 6, 1994[51] | |

Secretary of State of Missouri | Removed by the Missouri Supreme Court on December 12, 1994[52] |

| November 11, 2004[53] | Kathy Augustine |

Nevada State Controller | Censured on December 4, 2004, not removed from office[54] |

| April 11, 2006[55] | |

Member of the University of Nebraska Board of Regents | Removed by the Nebraska Supreme Court on July 7, 2006[56] |

| January 8, 2009 (first vote)[57] |  Rod Blagojevich |

Governor of Illinois | 95th General Assembly ended |

| January 14, 2009 (second vote)[58] | Removed on January 29, 2009, and declared ineligible to hold public office in Illinois[59] | ||

| February 11, 2013[60] |  Benigno Fitial |

Governor of the Northern Mariana Islands | Resigned on February 20, 2013 |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Impeachment in the United States. |

- Censure in the United States

- Efforts to impeach George W. Bush

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal officials

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal judges

- Jefferson's Manual

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- Recall election

Notes

- ↑ "Removed and disqualified" indicates that following conviction the Senate voted to disqualify the individual from holding further federal office pursuant to Article I, Section 3 of the United States Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part, that "[j]udgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States."

- ↑ During the impeachment trial of Senator Blount, it was argued that the House of Representatives did not have the power to impeach members of either House of Congress; though the Senate never explicitly ruled on this argument, the House has never again impeached a member of Congress. The Constitution allows either House to expel one of its members by a two-thirds vote, which the Senate had done to Blount on the same day the House impeached him (but before the Senate heard the case).

- ↑ Judge Nixon later challenged the validity of his removal from office on procedural grounds; the challenge was ultimately rejected as nonjusticiable by the Supreme Court in Nixon v. United States, 506 U.S. 224 (1993).

References

- ↑ Cole, J.P.; Garvey, T. (October 29, 2015). "Impeachment and Removal" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Congressional Research Service. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Josh Chafetz (2010). "Impeachment and Assassination". 95. Minnesota Law Review

- ↑ "Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials" (PDF). law.cornell.edu.

- ↑ http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/3_1986SenatesImpeachmentRules.pdf

- ↑ Welcome to The American Presidency

- ↑ John R. Labovitz, "Presidential Impeachment", p.132. (New Haven: Yale University Press 1978)

- ↑ Lyons, Richard; Chapman, William (July 28, 1974). "Judiciary Committee Approves Article to Impeach President Nixon, 27 to 11". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Kilpatrick, Carroll (August 9, 1974). "Nixon Resigns". The Washington Post.

- ↑ The Constitution of the United States, Article 1, Section 3. "The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present."

- ↑ "Someone Should Have Told Spiro Agnew" by Stokes Paulsen, Michael – Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 14, Issue 2, Summer 1997 | Questia, Your Online Research Library. Questia.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Articles And Essays: Can The Vice President Preside At His Own Impeachment Trial?: A Critique Of Bare Textualism. Litigation-essentials.lexisnexis.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Staff (n.d.). "Chapter 4: Complete List of Senate Impeachment Trials". United States Senate. Retrieved 2010-12-08. (Archived by WebCite)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 U.S. Joint Committee on Printing (September 2006). "Impeachment Proceedings". Congressional Directory. Retrieved 2009-06-19. (Archived by WebCite)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 staff (n.d.). "Impeachments of Federal Judges". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved 2010-12-08. (Archived by WebCite)

- ↑ "1801: Senate Tries Supreme Court Justice". 25 November 2014.

- ↑ PBS NewsHour

- 1 2 staff (n.d.). "Judges of the United States Courts – Delahay, Mark W.". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Hinds' Precedents, Volume 3 - Chapter 78 - The Impeachment and Trial of Charles Swayne".

- ↑ Gamboa, Suzanne (2009-06-30). "White House accepts convicted judge's resignation". AP. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-22. (Archived by WebCite)

- ↑ Gamboa, Suzanne (2009-07-22). "Congress ends jailed judge's impeachment". AP. Archived from the original on September 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-08. (Archived by WebCite)

- ↑ Powell, Stewart (2009-06-19). "U.S. House impeaches Kent". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

In action so rare it has been carried out only 14 times since 1803, the House on Friday impeached a federal judge — imprisoned U.S. District Court Judge Samuel B. Kent...

(Archived by WebCite) - ↑ Alpert, Bruce; Jonathan Tilove (2010-12-08). "Senate votes to remove Judge Thomas Porteous from office". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ Alpert, Bruce (2010-03-11). "Judge Thomas Porteous impeached by U.S. House of Representatives". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ↑ Tentative description of a dinner given to promote the impeachment of President Dwight Eisenhower: [poem] by Lawrence Ferlinghetti; City Lights Books: (1958)

- ↑ Clark, Richard C. (2008-07-22). "McFadden's Attempts to Abortababy the Federal Reserve System". Scribd. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

Though a Republican, he moved to impeach President Herbert Hoover in 1932 and introduced a resolution to bring conspiracy charges against the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

- ↑ "National Affairs: Texan, Texan & Texan". Time. January 25, 1932. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ NYS Constitution, Article VI, § 24

- ↑ Staff reporter (2004-06-21). "Embattled Conn.governor resigns". AP. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ "House votes to impeach Blagojevich again". Chicago Tribune. 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ Bateman, Newton; Paul Selby; Frances M. Shonkwiler; Henry L Fowkes (1908). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois. Chicago, IL: Munsell Publishing Company. p. 489.

- 1 2 3 "Impeachment of State Officials". Cga.ct.gov. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- 1 2 Blackmar, Frank (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History. Standard Publishing Co. p. 598.

- ↑ "Letters Relating to the Efforts to Impeach Governor Harrison Reed During the Reconstruction Era". floridamemory.com. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ↑ "State Governors of Louisiana: Henry Clay Warmoth". Enlou.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-06. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ↑ "SULZER IMPEACHED BY ASSEMBLY BUT REFUSES TO SURRENDER OFFICE", Syracuse Herald, August 13, 1913, p1

- ↑ "HIGH COURT REMOVES SULZER FROM OFFICE BY A VOTE OF 43 TO 12", Syracuse Herald, October 17, 1913, p1

- ↑ Block, Lourenda (2000). "Permanent University Fund: Investing in the Future of Texas". TxTell (University of Texas at Austin). Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ Official Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana, April 6, 1929 pp. 292-94

- ↑ "Raulston Schoolfield, Impeached Judge, Dies". UPI. October 8, 1982. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ "Impeachment Trial Finds Judge Guilty". AP. July 11, 1958. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ Staff reporter (1984-03-14). "Attorney General is Impeached". AP. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- ↑ Staff reporter (1984-05-04). "Nebraskan Found Not Guilty". AP. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- ↑ Gruson, Lindsey (1988-02-06). "House Impeaches Arizona Governor". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Gruson, Lindsey (1988-04-05). "Arizona's Senate Ousts Governor, Voting Him Guilty of Misconduct". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Staff reporter (1989-03-30). "Impeachment in West Virginia". AP. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ↑ Wallace, Anise C. (1989-07-10). "Treasurer of West Virginia Retires Over Fund's Losses". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ↑ "Kentucky House Votes To Impeach Jailed Official". Orlando Sentinel. 1991-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

The House voted unanimously Friday to impeach the agriculture commissioner six days after he began serving a one-year sentence for a payroll violation.

- ↑ "Jailed Official Resigns Before Impeachment Trial". Orlando Sentinel. 1991-02-07. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

Kentucky's commissioner of agriculture, serving a one-year jail sentence for felony theft, resigned Wednesday hours before his impeachment trial was scheduled to begin in the state Senate.

- ↑ Hinds, Michael deCourcy (1994-05-25). "Pennsylvania House Votes To Impeach a State Justice". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

A State Supreme Court justice convicted on drug charges was impeached today by the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

- ↑ Moushey, Bill; Tim Reeves (1994-10-05). "Larsen Removed Senate Convicts Judge On 1 Charge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA USA. p. A1. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

Rolf Larsen yesterday became the first justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to be removed from office through impeachment. The state Senate, after six hours of debate, found Larsen guilty of one of seven articles of impeachment at about 8:25 p.m, then unanimously voted to remove him permanently from office and bar him from ever seeking an elected position again.

- ↑ Young, Virginia (1994-10-07). "Moriarty Is Impeached – Secretary Of State Will Fight Removal". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO USA. p. 1A. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

The House voted overwhelmingly Thursday to impeach Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty for misconduct that "breached the public trust." The move, the first impeachment in Missouri in 26 years, came at 4:25 p.m. in a hushed House chamber.

- ↑ Young, Virginia; Kim Bell (1994-12-13). "High Court Ousts Moriarty". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO USA. p. 1A. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

In a unanimous opinion Monday, the Missouri Supreme Court convicted Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty of misconduct and removed her from office.

- ↑ Vogel, Ed (2004-11-12). "Augustine impeached". Review-Journal. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Whaley, Sean (2004-12-05). "Senate lets controller keep job". Review-Journal. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Jenkins, Nate (2006-04-11). "Hergert impeached". Lincoln Journal Star. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

With the last vote and by the slimmest of margins, the Legislature did to University of Nebraska Regent David Hergert Wednesday what it hadn’t done in 22 years — move to unseat an elected official.

- ↑ Staff reporter (2006-08-08). "Hergert Convicted". WOWT-TV. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

University of Nebraska Regent David Hergert was convicted Friday of manipulating campaign-finance laws during his 2004 campaign and then lying to cover it up. The state Supreme Court ruling immediately removed Hergert, 66, from office.

- ↑ Staff reporter (2009-01-09). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". AP. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Mckinney, Dave; Jordan Wilson (2009-01-14). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Long, Ray; Rick Pearson (2009-01-30). "Blagojevich is removed from office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Haidee V. Eugenio (2009-01-09). "CNMI governor impeached on 13 charges". Saipan Tribune. Retrieved 2013-09-14.