Invasive species in the United States

Invasive species are a significant threat to many native habitats and species of the United States and a significant cost to agriculture, forestry, and recreation. The term "invasive species" can refer to introduced or naturalized species, feral species, or introduced diseases. Some species, such as the dandelion, while non-native, do not cause significant economic or ecologic damage and are not widely considered as invasive. Overall, it is estimated that 50,000 non-native species have been introduced to the United States, including livestock, crops, pets, and other non-invasive species. Economic damages associated with invasive species' effects and control costs are estimated at $120 billion per year.[1]

Notable invasive species

For a more complete list of invasive species, see List of invasive species in North America

| Picture | Name | Species Name | Introduced | Control Measures | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | Kudzu | Pueraria lobata | Southern U.S. | Mowing, herbicides, conservation grazing | Known as "the vine that ate the south", forms dense monocultures that outcompete native ground cover and forest trees. Can grow by up to one foot a day. |

| Tumbleweed | Kali tragus | Throughout North America | Managed grazing | Introduced through imported flaxseed from Russia that was contaminated with Kali seeds. Although invasive, it was used in Westerns to symbolize frontier areas of the United States. |

| Privet | Ligustrum spp. | Southeastern U.S. | Mechanical removal, herbicides | Highly invasive in urban areas and forested area of the southeastern U.S. |

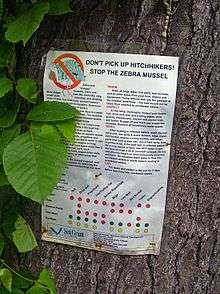

| Zebra mussels | Dreissena polymorpha | Great Lakes, U.S. waterways & lakes | Ballast water transport bans, manual removal from clogged pipes | Initially spread by ballast tanks of oceangoing vessels on the Great Lakes, now spread lake-to-lake by trailer-drawn boats. May be a source of avian botulism in the Great Lakes region. |

| | European starlings | Sturnus vulgaris | Lower 48 states | Hunting, trapping | Introduced in 19th century as part of an effort to bring all species mentioned in Shakespeare's works to the United States. 100 birds released in Central Park have spread all over the mainland U.S. |

| Brown tree snake | Boiga irregularis | Guam | Dog-sniffing of incoming ships, paracetamol as poison | Has reached densities on Guam of up to 100 snakes per hectare, caused extinction on Guam of at least 12 bird species |

| Burmese pythons | Python molarus | Everglades | Hunting season created | Introduced by hurricane damage to breeding facilities. |

| Africanized bee | Apis hybrid | Southwestern U.S. | Cold weather has limited spread | Hybrid of African and European honeybees created in Brazil in the 1950s, described as "Killer bees." While individually no more poisonous than common honeybee, attacks are particularly violent and usually involve large numbers of stings, which can be cumulatively fatal to animals and people. |

| Asian carp | Multiple Cyprinidae | Mississippi River and tributaries | Rotenone poison, electric barriers | Have the habit of jumping out of the water, which can injure boaters. Introduced to eat algae in fish ponds in Southern U.S., escaped during flood events. |

| Emerald ash borer | Agrilus planipennis | Eastern U.S. | Culling infected stands, bans on firewood transport | Threatens to severely reduce or eliminate the ash lumber industry of U.S., worth an estimated value of $25.1 billion per year |

| Hemlock woolly adelgid | Adelges tsugae | Eastern U.S. | Insecticide treatment | Could kill most eastern hemlocks in the U.S. within the next decade |

| Multiflora rose | Rosa multiflora | Eastern U.S. | Manual removal, herbicides[2] | Introduced for erosion control and promoted as a "living fence" to attract wildlife, now competes with native understory plants |

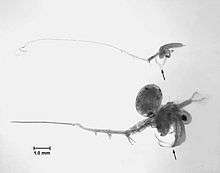

| Spiny waterflea | Bythotrephes longimanus | Great Lakes | Ballast water transport bans | Competes with native fish for prey, spines prevent many native fish from eating it as prey |

| Snakehead fish | Channa argus | East Coast fresh water | Since 2002 it has been illegal to possess a live snakehead in many U.S. states. As of July 2002, snakeheads are being sold in live fish food markets and some restaurants in Boston and New York. Live specimens have been confiscated by authorities in Alabama, California, Florida, Texas and Washington, all states where possession of these fish is illegal. Also, snakeheads are readily available for purchase over the Internet.[3] | Snakeheads can become invasive species and cause ecological damage because they are top-level predators, meaning they have no natural enemies outside of their native environment. Each spawning-age female can release up to 15,000 eggs at once. Snakeheads can mate as often as five times a year. This means in just two years, a single female can release up to 150,000 eggs. |

Economic impacts of invasive species

The economic impacts of invasive species can be difficult to estimate, especially when an invasive species does not affect economically important native species. This is due in part to the difficulty in determining the non-use value of native habitats damaged by invasive species, and in part to incomplete knowledge of the effects of all of the invasive species present in the U.S. Estimates for the damages caused by well-known species can vary as well. The Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) has estimated zebra mussel economic effects at $300,000 a year, while an ACoE study put the number at $1 billion. The United States government spends an estimated $1 billion to recover from the invasive Formosan termite, investing $300 million of this budget is spent in areas surround New Orleans, a major port city.[4] Estimates of total yearly costs due to invasive species range from $1.1 billion per year to $137 billion per year.[5]

In 1993, the OTA estimated that a total of $100 million is invested annually in invasive species aquatic weed control in the US.[6] Introduced rats cause more than $19 billion per year in damages,[7] exotic fish cause up to $5.4 billion annually, and the total costs of introduced weeds are estimated at around $27 billion annually.[8] The total damage to the U.S. native bird population due to invasive species is approximately $17 billion per year. Approximately $2.1 billion in forest products are lost each year to invasive plant pathogens in the United States, and a conservative estimate of the losses to U.S. livestock from exotic microbes and parasites was $9 billion per year in 2001.[9]

Government polices and management efforts

The federal government has historically promoted the introduction and widespread distribution of species that would become invasive, including multiflora rose, kudzu, and others for numerous reasons. Before the 20th century, numerous species were imported and released without government oversight, such as the gypsy moth and house sparrow. Over 50% of flora recognized as invasive or noxious weeds were deliberately introduced to the United States, by either government policy or individuals.[10] Current government policy can be broadly separated into two categories: preventing entry of a potential invasive species and controlling the spread of species already present. This is carried out by different government agencies, depending on what types of damage a species can cause.

Regulations designed to prevent entry of invasive species

The Lacey Act of 1900, originally designed to protect game wildlife, its role has increased to prohibit parties from bringing non-native species that have the potential to become invasive into the United States. The Lacey Act gives the FWS the power to list a species as "injurious" and regulate or prohibit its entry into the U.S.[11] The Alien Species Prevention and Enforcement Act of 1992 makes it illegal to transport a plant or animal deemed injurious into the United States through the mail. The FWS concerns itself mostly with the invasive species likely to threaten sensitive habitats or endangered species.

The USDA is also involved in preventing the introduction of invasive species, largely through the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS. APHIS was originally tasked with preventing damage to agriculture and forestry from alien species, pests, or diseases, but has had its mission expanded to include preventing invasive species spread as well.[12] This includes identifying potential pests and diseases, assisting in international and domestic eradication efforts, and the Smuggling Interdiction and Trade Compliance Program, designed initially to deal with illegally imported produce, but now tasked with preventing the entry of exotic pests, diseases, and potentially invasive species.[13] APHIS also enforces bans against interstate transport of pests, diseases, and species listed as injurious, noxious weeds, or nuisance species. An example of the USDA banning imports is the ban on fresh mangosteen fruit due to concerns about fruit flies from southeast Asia. This ban originally allowed only frozen or canned fruit, but now allows for fresh irradiated fruit to enter.[14]

Reducing the spread of dangerous invasive species

Many invasive species are spread inadvertently by human activities, such as seeds stuck to clothing or mud transporting firewood, or through ballast water. The government has instituted several different policies related to different pathways the invasive species may be spread. For example, quarantines on a federal and state level exist for firewood across the Eastern United States in an attempt to halt the spread of the emerald ash borer, gypsy moth, oak wilt, and others. Transporting firewood out of quarantine zones can result in a fine of up to $1,000,000 and 25 years in jail, but punishments are usually much lower.[15]

The techniques available for controlling the spread of invasive species can be broadly defined into 6 categories:[16]

- Cultural practices

- Controlled burns and timbering. An example of this in action is the use of prescribed burns in the Everglades to control Melaleuca quinquenervia trees. The burns destroy Melaleuca, but not native species which have adapted to wildfires, which were common, but are now suppressed.[17]

- Interference with dispersal

- May include fencing, reducing accidental seed transport, and the construction of barriers, such as the electric barrier on the Chicago Sanitary & Ship Canal, discussed below.

- Mechanical removal

- Includes mowing, harvesting, manual removal, trapping, & culling. Many invasive plants, such as garlic mustard, can regrow quickly after mowing and must be removed by the roots or chemically.

- Chemical control

- May include the use of any approved pesticide or herbicide, or vaccines to control invasive diseases. Sea lampreys in the Great Lakes have had their numbers significantly reduced by a lampricide that kills larvae, which hatch in streams, before they can enter the lakes. The lampricide is responsible for reducing the sea lamprey population in the Great Lakes from over 3 million in the 1950s to around 450,000 today, and with potentially rescuing several Great Lakes fisheries.[18]

- Biological control

- Can involve the release of specific predators/herbivores, parasites, or diseases designed to control an invasive species without damaging native ones. One example of this is the city of Chattanooga's use of goats to control kudzu growing on mountain ridges. The goats, guarded from predators by llamas, eat the vine often enough to slowly starve the roots, killing the plant. This method is much cheaper than the repeated mowing or herbicidal spraying that would otherwise be necessary.[19] Goats reach areas which are inaccessible to machines and have multichambered stomachs which coupled with their grazing technique mean that goats leave few seeds behind to sprout again.[20]

- Interference with reproduction

- This can include the release of mating-disrupting pheromones or the release of sterile males. Field tests are underway to study the control of sea lampreys in the Great Lakes by the use of pheromone-baited traps in streams, in addition to current chemical controls. When female sea lampreys return to the stream to breed, they are drawn to the traps and captured, preventing reproduction from occurring.[18]

An integrated pest management (IPM) approach, as defined by the National Invasive Species Council, uses scientific data and population monitoring to help determine the most efficient control strategy, which is usually a combination of several of the methods listed above. Agencies are encouraged to use an adaptive management strategy, involving regular reviews on the efficiency of their policies and conduct research into better methods.[16]

Inter-department co-operation

Invasive species control is not overseen by one government agency. Rather, different invasive species are controlled by different agencies. For example, policies aimed at controlling the emerald ash borer are undertaken by the USDA, because National Forests, the body coordinating emerald ash borer control efforts, are within the USDA.[21] The National Invasive Species Council was created by executive order in 1999 and charged with promoting efficiency and coordination between the numerous federal invasive species prevention and control policies. The NISC is co-chaired by the secretaries of the three federal departments that are charged with invasive species control: Interior, Agriculture, and Commerce. [22] Many state efforts use a similar council model to coordinate agencies within a state.

Education and outreach

Many of the policies used to contain invasive species, such as firewood transport bans or cleaning shoes and clothes after hiking are effective only when the general public knows of their existence and importance. Because of this numerous programs to inform the public about invasive species. This includes placing signs at boat ramps, campsites, state borders, hiking trails, and numerous other locations as reminders of policies and potential fines associated with breaking policies. There are also numerous government programs aimed at educating children,[23] promoting volunteer efforts at removal, and the many ways citizens can prevent the spread of invasive species.[24]

Invasive species by area

Great Lakes

Current efforts in the Great Lakes ecoregion focus on measures that prevent the introduction of invasive species. As a major transport area, a number of invasive species have already been established within the Great Lakes. In 1998, the United States Coast Guard, in accordance with the National Invasive Species Act of 1996, established a set of voluntary ballast water management program. In 2004 this voluntary program became mandatory for every ship entering US controlled waters.[25] Current measures are among the most stringent in the world and require ships entering from outside the Exclusive Economic Zone to flush ballast water in open seas or retain their ballast water for the length of their stay in the Great Lakes.[26][27] Failure to comply with the US Coast Guards regulations can result in a class C felony.[28]

Another preventative measure in the Great Lakes region is the presence of an electrified barrier in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. The barrier is meant to keep Asian carp from reaching Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes. On December 2, 2010, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin were denied their request to force the closing the Canal by Judge Robert Dow of the United States District Court for Northern District of Illinois.[29][30] The closing of the Canal would have once again permanently separated Lake Michigan and the Mississippi river system. States argued that the canal, and the Asian carp in it, posed a risk to $7 billion worth of industry.[31] Currently the electric barrier is the only preventative measure and some question its effectiveness, particularly following the discovery of Asian carp DNA past the barrier.[32] The discovery of DNA of Asian carp could be linked to live bait used around the Great Lakes region. The method for identifying the DNA is called environmental DNA (eDNA) surveillance. This method uses DNA, that is left in the environment, to identify species in low abundances.

Rocky Mountain Region.

The USDA Rocky Mountain Research Station (RMRS) has a specific Invasive Species Working Group[33] to do the research about invasive species in Rocky Mountain region. The Invasive Species Working Group focuses on four key areas: (1) prediction and prevention, (2) early detection and rapid response, (3) control and management, and (4) restoration and rehabilitation.[5] Specific approaches include prioritizing of invasive species problems, increased collaboration among agencies regarding those problems, and accountability for the responsible use of the limited resources available for invasive control.[34]

Invasive species of particular concern in the Rocky Mountain region include: cheatgrass; leafy spurge; tansy ragwort; spotted knapweed; bufflegrass; saltcedar; white pine blister rust; armillaria root rot; introduced trout species; golden algae; spruce aphid; and banded elm bark beetle.[35]

Colorado River

Already stressed by water management and damming, the Colorado River of Western United States is losing its big-river fish community to combined effects of predation and competition by introduced non-native fishes. This fish community includes four large fishes that are listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. One of these, the Colorado pikeminnow (AKA white or Colorado river salmon, Ptychocheilus lucius) is the largest minnow native to North America, and it is well known for its spectacular fresh water spawning migrations and homing ability. Despite a massive recovery effort, its numbers decline. Hampered by a loss of about 80% of its habitat, the young of this once abundant fish is overwhelmed in its nursery habitat by invasive small fishes (such as red shiner and fathead minnow), whose numbers are as high as 90% of the standing stocks. Its juveniles and adults now must also compete with and are preyed upon by introduced northern pike, channel and flathead catfishes, large and smallmouth basses, common carp, and other fishes.[36]

Invasive species by state

Arizona

California

California has created a policy system towards invasive species, including Invasive Species Council of California (ISCC), California Invasive Species Advisory Committee (CISAC) and California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC), a non-profit organization. The ISCC represents the highest level of leadership and authority in state government regarding invasive species. The ISCC is an inter-agency council that helps to coordinate and ensure complementary, cost-efficient, environmentally sound and effective state activities regarding invasive species. CISAC advises the ISCC, and created the California list of invasive species California has many diverse ecoregions, and numerous endemic species that are at risk from invasive species.[37]

Florida

Florida Everglades

Invasive species in Florida currently make up more than 26% of the animal population and a full one third of the flora population.[38] In 1994, the Everglades Forever Act of 1994 was passed to help in controlling Florida's water supply, recreation areas, and diverse flora and fauna.[39] In addition to control and prevention measures the act also calls for efforts to monitor the distribution of known invasive species.[40]

One invasive species occurring in the Everglades that can have serious consequences is the Burmese python. Between 2000 and 2010, approximately 1,300 of the snakes were removed from the Everglades.[41] Currently the National Park Service is researching control measures for the Burmese python in order to limit the species effects on the delicate Everglades ecosystem.[42]

In 2015, the presence of the invasive land planarian Platydemus manokwari was recorded from several gardens in Miami. Platydemus manokwari is a predator of land snails and is considered a danger to endemic snails wherever it has been introduced.[43]

Hawaii

In Hawaii measures to prevent the introduction and spread of invasive species are coordinated by the Hawaii Invasive Species Council.[44] Currently the council is broken into five committees which focus on different areas of invasive species control. These focus areas are (1) prevention (2) management of established pests (3) increased public awareness (4) research and technology and (5) monetary resources.

Currently, Hawaii requires inspection of any and all plant, animal and microorganism transports.[45] This includes transports from the mainland in addition to transports occurring between islands. Travelers are required to fill out a declaration form for each journey. Failure to declare these transports can result in up to one year imprisonment or a $250,000 fine.[46] Many potential invasives or carriers for invasives require permits and quarantine periods before entry to the state is allowed.[47]

In addition, there are other preventative measures such as a hotline for reporting sightings of known potential invaders like the brown tree snake.[48]

Idaho

The Idaho Department of Agriculture (U.S.) has around 300 introduced or exotic species listed with 36 classified as noxious weeds (invasive species). The legal designation of noxious weed for a plant species can use these four criteria:[49]

- It is present in but not native to state-province-ecosystem.

- It is potentially more harmful than beneficial to that area.

- Its management, control, or eradication is economically and physically feasible.

- The potential adverse impact of it exceeds the cost of its control.

Some of the plants on Idaho's noxious weed list that are harmful or poisonous are:

- Leafy spurge: native to Eurasia. It has a milky latex in all its parts that can produce blisters and dermatitis in humans, cattle, and horses and may cause permanent blindness if rubbed into an eye.

- Poison hemlock: native to Europe. It contains highly poisonous alkaloids toxic to all classes of domesticated grazing animals.

- Russian knapweed: native to the Caucasus in southern Russia and Asia. It causes chewing disease in horses.

- Tansy ragwort: native to Eurasia. All parts are poisonous, it causes liver damage to cattle and horses, while it affects sheep to a lesser extent.

- Toothed spurge: native to the Great Plains region. A milky latex exists in all parts of the plant that can produce blisters and dermatitis in humans, cattle, and horses. It may cause permanent blindness if rubbed into the eye.

- Yellow starthistle: native to the Mediterranean basin area and Asia. It causes death and chewing disease in horses.

- Yellow toadflax: native to Europe. It contains a poisonous glucoside that may be harmful to livestock.

Louisiana

The city of New Orleans, the "gateway to the Mississippi", is a porous port city with rich soils. In turn, many aquatic plants are introduced to the region, making Louisiana the state with the second largest list of invasive aquatic species,[50] second to Florida.

The "Dirty Dozen"[51] details a list of the United States' most destructive invasive species. Of the twelve, four are identified in the state, including the zebra mussel, tamarisk, hydrilla, and Chinese tallow.

Maryland

Nevada

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

Invasive species pose a threat to wildlife, habitat, waterways, economy, and the health of humans in New York State. The NY Department of Environmental Conservation (NYDEC)works with stewards of natural resources, non-profits and citizen scientists to detect, record and manage invasive species. These collaborations are organized into 8 Partnerships for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISMs) throughout NYS. THE PRISMS were formed under Title 17, Environmental Conservation Law 9-1705(5)(g).

According to NYDEC [52] PRISMS perform the following tasks: plan regional invasive species management;develop early detection and rapid response capacity;implement eradication projects; educate the public in cooperation with DEC contracted Education and Outreach providers; coordinate PRISM partners; recruit and train volunteers; support research through citizen science. [53]

Terrestrial species of high concern in New York include

- Acer platanoides—Norway maple

- Ailanthus altissima—Tree of heaven

- Alliaria petiolata—Garlic mustard

- Ampelopsis glandulosa—Porcelain berry

- Aralia elata—Japanese angelica tree

- Berberis thunbergii—Japanese barberry

- Celastrus orbiculatus—Asian bittersweet

- Euonymus alatus—Burning bush

- Fallopia japonica—Japanese knotweed

- Lonicera japonica—Japanese honeysuckle

- Lonicera maackii—Bush honeysuckle

- Microstegium vimineum—Japanese stiltgrass

- Miscanthus sinensis—Chinese silvergrass

- Ranunculus ficaria—Lesser celandine

- Rosa multiflora—Multiflora rose

- Rubus phoenicolasius—Wineberry

Aquatic species of high concern in New York include

- Trapa natans L.—Water chestnut

- Myriophyllum spicatum—Eurasian Watermilfoil

- Hydrilla verticillata—Hydrilla

Insects

- Anoplophora glabripennis—Asian Longhorned Beetle

- Agrilus planipennis—Emerald Ash Borer

See also

- List of invasive species in North America

- List of invasive species in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States

- Environmental issues in the United States

- Fauna of the United States

References

- ↑ David Pimentel, Rodolfo Zuniga, Doug Morrison. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecological Economics. 52 (2005) 273-288.

- ↑ "Invasive Species: Plants - Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)". Invasivespeciesinfo.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ http://www.dnr.state.md.us/fisheries/snakeheadfactsheetedited.pdf

- ↑ "Louisiana Invasive Species". is.cbr.tulane.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- 1 2 "Invasive Species Research - Rocky Mountain Research Station - USDA Forest Service". Rmrs.nau.edu. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ OTA, 1993. Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States. Office of Technology Assessment, United States Congress, Washington, DC.

- ↑ USDA, 2001. Agricultural Statistics. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC

- ↑ Pimentel, D., Lach, L., Zuniga, R., Morrison, D., 1999. Environmental and economic costs associated with introduced nonnative species in the United States. Manuscript, pp. 1– 28.

- ↑ David Pimentel, Rodolfo Zuniga, Doug Morrison. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecological Economics. 52 (2005) 273-288

- ↑ The United States Naturalized Flora: Largely the Product of Deliberate Introductions Richard N. Mack and Marianne Erneberg. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Vol. 89, No. 2 (Spring, 2002), pp. 176-189

- ↑ "Nation marks Lacey Act centennial, 100 years of federal wildlife law enforcement. US Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved on July 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Usda - Aphis - About Aphis". Aphis.usda.gov. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "USDA - APHIS - International Safeguarding - Services". Aphis.usda.gov. 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Karp, David (8 August 2007). "Mangosteens Arrive, but Be Prepared to Pay". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ "Web Page Redirect - Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources". Dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- 1 2 "Guidelines for ranking invasive species control projects. Volume I." National Invasive Species Council. May, 2005. http://www.invasivespecies.gov/global/CMR/CMR_documents/NISC%20Control%20and%20Management%20Guidelines.pdf

- ↑ "In Practice - Prescribed Burning: Management Methods - Managing Invasive Plants". Fws.gov. 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- 1 2 "Pheromones in river traps attract sea lampreys". Great Lakes Echo. 2009-05-11. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Emery, Theo (5 June 2007). "In Tennessee, Goats Eat the 'Vine That Ate the South'". The New York Times.

- ↑ Jolly, Joanna. "The goats fighting America's plant invasion". BBC Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Emerald Ash Borer Beetle (EAB) | Stop The Beetle". Stopthebeetle.info. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Emerton, L. and G. Howard, 2008, A Toolkit for the Economic Analysis of Invasive Species. Global Invasive Species Programme, Nairobi.

- ↑ "Invasive Species: Manager's Tool Kit - Outreach Tools". Invasivespeciesinfo.gov. 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "What Can You Do - Invasive Species - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". Fws.gov. 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Ballast Water Management". Uscg.mil. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Seaway System - The Environment - Ballast Water". Greatlakes-seaway.com. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "SERC - Marine Invasions: Mid-ocean Ballast Water Exchange". Serc.si.edu. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Aquatic Nuisance Species". Uscg.mil. 2011-01-04. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Another setback in the legal fight to keep Asian carp out of the Great Lakes". Great Lakes Law. 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Case: 1:10-cv-04457 Document #: 155 Filed: 12/02/10 Page 1 of 61 PageID #:4980" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Egan, Dan (2010-01-05). "Illinois fights back over carp lawsuit". JSOnline. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Chicago waterway gets third electric barrier aimed at keeping Asian carp out of Great Lakes". TwinCities.com. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Invasive Species Working Group - Rocky Mountain Research Station - USDA Forest Service". Rmrs.nau.edu. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "A Framework for the Development of the National Invasive Species Management Strategy for the USDA Forest Service" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Research Summary and Expertise Directory" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ H.M. Tyus and J.F. Saunders 2000. Nonnative fish control and endangered fish recovery: Lessons from the Colorado River. Fisheries 25(9):17-24)

- ↑ "Welcome to the Invasive Species Council of California". Iscc.ca.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Ferriter, et al (2001) http://mytest.sfwmd.gov/portal/page/portal/pg_grp_sfwmd_sfer/portlet_prevreport/consolidated_01/chapter%2014/ch14.pdf

- ↑ Florida Statutes Chapter 373.4592, http://exchange.law.miami.edu/everglades/statutes/state/florida/E_forever.htm

- ↑ Ferriter, "et al" (2001) http://mytest.sfwmd.gov/portal/page/portal/pg_grp_sfwmd_sfer/portlet_prevreport/consolidated_01/chapter%2014/ch14.pdf

- ↑ "Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing Three Python Species and One Anaconda Species as Injurious Reptiles". Fish and Wildlife Service. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Natural Resources Management - Burmese Pythons" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Justine, Jean-Lou; Winsor, Leigh; Barrière, Patrick; Fanai, Crispus; Gey, Delphine; Han, Andrew Wee Kien; La Quay-Velázquez, Giomara; Lee, Benjamin Paul Yi-Hann; Lefevre, Jean-Marc; Meyer, Jean-Yves; Philippart, David; Robinson, David G.; Thévenot, Jessica; Tsatsia, Francis (2015). "The invasive land planarianPlatydemus manokwari(Platyhelminthes, Geoplanidae): records from six new localities, including the first in the USA". PeerJ. 3: e1037. doi:10.7717/peerj.1037. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ↑ "Hawaii Invasive Species Council (HISC)". Hawaiiinvasivespecies.org. 2003-10-29. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Plant Quarantine — Hawaii Department of Agriculture". Hawaii.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Exhibit 3. State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture Plants and Animals Declaration Form" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions on Import and Export Regulations of Plant Species". Hawaiiplants.com. 2010-12-15. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Brown Tree Snake Program — Hawaii Department of Agriculture". Hawaii.gov. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Prather, Timothy (2002). Idaho's Noxious Weeds. University of Idaho.

- ↑ "Nonindigenous Aquatic Species". nas.er.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ "The dirty dozen: 12 of the most destructive invasive animals in the United States". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ NYDEC PRISM Fact Sheet, http://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/lands_forests_pdf/prismfactsheet.pdf

- ↑ NY Invasive Species Information, http://nyis.info/index.php

Further reading

- Coates, Peter (2007). American Perceptions of Immigrant and Invasive Species: Strangers on the Land. University of California Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-520-24930-5.

External links

- Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States

- Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia

- Center for Invasive Species Research at the University of California, Riverside

- Invasive Species Specialist Group - global invasive species database

- Invasive Species Research at the Rocky Mountain Research Station

- National Invasive Species Information Center, National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for invasive species.

- Weeds at the Bureau of Land Management

- The Nature Conservancy's Great Lakes Project- Aquatic Invasive Species

- Invasive and Noxious Weeds the Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Noxious Weed Program at the Department of Agriculture

- By state

- Montana's Weed Awareness Program: Pulling Together

- Noxious Weed Photos, King County, Washington State

- cal-ipc: "Noxious Weed definitions"