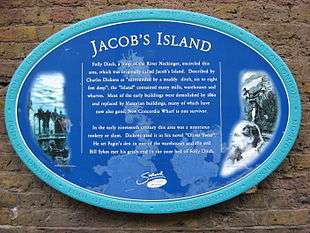

Jacob's Island

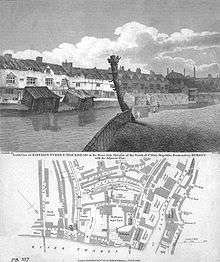

Jacob's Island was a notorious rookery in Bermondsey, on the south bank of the River Thames in London. It was separated from Shad Thames to the west by St Saviour's Dock, the point where the subterranean River Neckinger enters the Thames, and on the other two sides by tidal ditches, one just west of George Row and the other just north of London Street (now named Wolseley Street).

History

The extent of the historic Jacob's Island is approximately delineated by Mill Street, Bermondsey Wall West, George Row and Wolseley Street.

Jacob's Island was once notoriously squalid and described as "The very capital of cholera" and "The Venice of drains" by the Morning Chronicle of 1849.[1] In the 1840s it also became 'a site of radical activity',[2] and, after attention from novelists Charles Dickens and Charles Kingsley, joined other London areas of 'literary-criminal notoriety' which emerged 'as symbols of a developing urban counterculture'.[3]

19th century social researcher Henry Mayhew described Jacob's Island as a "pest island" with "literally the smell of a graveyard" and "crazy and rotten bridges" crossing the tidal ditches, with drains from houses discharging directly into them, and the water harbouring masses of rotting weed, animal carcasses and dead fish.[4] He describes the water being "as red as blood" in some parts, as a result of pollutant tanning agents from the leather dressers in the area.[4][5]

The ditches were filled in the early 1850s, and the area later redeveloped as warehouses. In 1865, Richard King, writing in A Handbook for Travellers in Surrey, Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, observed that 'Many of the buildings have been pulled down since Oliver Twist was written, but the island is still entitled to its bad pre-eminence'.[6] A decade later, a missionary for the London City Mission provided a more positive report:

'The foul ditch no longer pollutes the air. It has long been filled up... there is now a good solid road... Part of London Street, the whole of Little London Street, part of Mill Street, beside houses in Jacob Street and Hickman's Folly, have been demolished. In most of these places warehouses have taken the place of dwelling-houses. The revolting fact of many of the inhabitants of the district having no other water to drink than that which they procured from the filthy ditches is also a thing of the past. Most of the houses are now supplied with good water, and the streets are very well paved. Indeed, so great is the change for the better in the external appearance of the district generally, that a person who had not seen it since the improvements would now scarcely recognise it.'[7]

Charles William Heckethorn had reservations about these improvements, telling readers of London Souvenirs in 1899, that 'Many of the horror's of Jacob's Island are now things of the past... in fact, the romance of the place is gone'.[8]

In 1934, a new public housing development called the Dickens Estate was opened.[9] Houses were named after Dickens' characters but the only one to have lived, and died, on Jacob's Island, the murderous Bill Sikes, was not honoured.[2]

Fiction

Charles Dickens

Jacob's Island was immortalised by Charles Dickens's novel Oliver Twist, in which the principal villain Bill Sikes dies in the mud of 'Folly Ditch'. Dickens provides a vivid description of what it was like:

"... crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem to be too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud and threatening to fall into it – as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage: all these ornament the banks of Jacob's Island."

Dickens was taken to this then-impoverished and unsavory location by the officers of the river police, with whom he would occasionally go on patrol.

.png)

Dickens wrote, in a preface to Oliver Twist, in March 1850, that in the intervening years his descriptions of the disease, crime and poverty of Jacob's Island had come to sound so fanciful to some that Sir Peter Laurie, a former Lord Mayor of London, had expressed his belief publicly that the location was a work of imagination and that no place by that name, or like it, had ever existed.[3][10] (Laurie had himself been fictionalised, a few years earlier, as Alderman Cute in Dickens' short novel The Chimes).[3]

Site of 'Bill Sikes' House'

In 1911, the Bermondsey Council opposed a suggestion by the London County Council that George's Yard, in Bermondsey, should be renamed Twist's Court, to reflect the site of the fictional home of the Dickens' character Bill Sikes.[11] Nine years later, G.W. Mitchell, a clerk with the Bermondsey Council found a plan dated 5 April 1855, in the London County Council archives, which showed 'Bill Sikes' house' marked on Jacob's Island.[12] This was at a time when the London County Council was proposing that Jacob's Island should be 'demolished'.[13] The following year, it was noted that 'so accurately' did Dickens' 'describe the scene that the house that he chose for Bill Sikes's end was easily located' in 1855, and 'became a Dickens' landmark', leading it to be marked on the Council's plan.[13] At the time of the 1920s news reports, the house, as shown in a reproduction of the 1855 plan,[13] was at 18 Eckell Street (formerly Edwards Street), in Metcalf Court,[13] and 'occupied as stables by Messers. R. Chartors and Co.'.[12] But 'in the time of a Dickens' it overlooked the Folly Ditch on one side and was approached by means of two wooden bridges across the mill stream',[12] and was 'used by thieves of the area'.[13]

In The Mysteries of Paris and London (1992), author Richard Maxwell describes a poster in 1846 inviting Jacob's Island residents to celebrate the end of the Corn Laws. Maxwell identifies the location given on the poster of 'that highly interesting Spot, described by Charles Dickens' as the site of Bill Sikes' house.[2]

Charles Kingsley

In Charles Kingsley's 1850 novel Alton Locke, the title character visits Jacob's Island and sees the death of the drunken Jimmy Downes, who's been reduced to poverty, and the bodies of his family, taken by Typhus.[14] Kingsley had been inspired by the accounts of the 1849 cholera epidemics published by the Morning Chronicle to visit Jacob's Island with his friend Charles Blachford Mansfield.[15] In addition to his fictional portrayal, Kingsley joined with Mansfield and fellow Christian socialist John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow in purchasing water-carts that were sent to Jacob's Island to supply clean drinking water to the residents.[15]

Modern era

The area was extensively bombed during the Second World War and today only one Victorian warehouse survives. It was one of the very first in Docklands to be converted to expensive loft apartments (in 1981) and has since been joined by new blocks of luxury flats, including a development by architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands. Over the past thirty years the Island area has undergone considerable regeneration and gentrification, with significant friction at times between the new land-based arrivals and the more bohemian set based in the houseboats moored just offshore at Reed Wharf.

See also

References

- ↑ Ackroyd, Peter (2011-03-30). "London Under: The lost catacombs of London". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- 1 2 3 Richard Maxwell (1992). The Mysteries of Paris and London. University of Virginia Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-8139-1341-4.

- 1 2 3 Simon Joyce (2003). Capital Offenses: Geographies of Class and Crime in Victorian London. University of Virginia Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8139-2180-8.

- 1 2 Charles John Chetwynd Talbot Shrewsbury (Earl of) (1852). Meliora: or, Better times to come: Being the contributions of many men touching the present state and prospects of society. Parker. pp. 276–280.

- ↑ in a letter to the Chronicle of 24 September 1849; from "Selections from London Labour and the London Poor", Oxford University Press, 1965, page xxxvi

- ↑ John Murray (Firm); Richard John KING (1865). A Handbook for Travellers in Surrey, Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight. By Richard J. King. With map. p. 2.

- ↑ Walford, Edward (1878). "IX". Old and New London. 6. pp. 100–117. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ↑ Heckethorn, Charles William (1899). London Souvenirs. Chatto & Windus. p. 248. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ↑ "CHRISTENING SETTLEMENTS.". The Canberra Times. National Library of Australia. 24 December 1934. p. 4. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ Charles Dickens (5 April 2005). Oliver Twist: (200th Anniversary Edition). Penguin Group US. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-1-101-07769-6.

- ↑ "OLIVER TWIST'S COURT.". West Gippsland Gazette. Warragul, Vic.: National Library of Australia. 8 August 1911. p. 3. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Where Bill Sykes Died.". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 28 September 1920. p. 6. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Jacob's Island and Bill Sikes' House.". The Chronicle. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 31 October 1925. p. 61. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Claudia Durst Johnson; Vernon Elso Johnson (2002). The Social Impact of the Novel: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-313-31818-4.

- 1 2 Edward R. Norman (3 October 2002). The Victorian Christian Socialists. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-53051-4.

Further reading

- The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson, Penguin Books, 2006, ISBN 1-4295-0131-6

External links

Coordinates: 51°30′05″N 0°04′14″W / 51.5013°N 0.0706°W