Janusz Korczak

| Janusz Korczak | |

|---|---|

|

Janusz Korczak, photographed c. 1930 | |

| Born |

Henryk Goldszmit 22 July 1878 (or 1879) Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died |

7 August 1942 (aged 64 or 63) Treblinka extermination camp, German-occupied Poland |

| Occupation | Children's author, humanitarian, pediatrician, child pedagogue and defender of children's rights |

Janusz Korczak, the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit[1] (22 July 1878 or 1879 – 7 August 1942[2]), was a Polish-Jewish educator, children's author, and pediatrician known as Pan Doktor ("Mr. Doctor") or Stary Doktor ("Old Doctor"). After spending many years working as director of an orphanage in Warsaw, he refused freedom and stayed with his orphans when the institution was sent from the Ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp, during the Grossaktion Warsaw of 1942.[3]

Biography

Korczak was born in Warsaw in 1878 or 1879 (sources vary[nb 1]) into the family of Józef Goldszmit,[1] a respected lawyer from a family of proponents of the haskalah,[5] and Cecylia née Gębicka, daughter of a prominent Kalisz family.[6] Born to a Jewish family, he was an agnostic in later life who did not believe in forcing religion on children.[7][8][9] His father fell ill around 1890 and was admitted to a mental hospital where he died six years later on 25 April 1896.[10][11] Spacious apartments were given up on Miodowa street, then Świętojerska.[12] As his family financial situation worsened, Henryk, still while attending the gymnasium (the current 8th Lyccee in Warsaw), begun to work as a tutor for other pupils.[12] In 1896 he debuted on the literary scene with a satirical text on raising children, Węzeł gordyjski.[6]

In 1898 he used Janusz Korczak as a writing pseudonym in the Ignacy Jan Paderewski Literary Contest. The name originated from the book Janasz Korczak and the Pretty Swordsweeperlady (O Janaszu Korczaku i pięknej Miecznikównie) by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski.[13] In the 1890s he studied in the Flying University. During the years 1898–1904 Korczak studied medicine at the University of Warsaw[4] and also wrote for several Polish language newspapers. After graduation he became a pediatrician. In 1905−1912 Korczak worked at Bersohns and Baumans Children's Hospital in Warsaw. During the Russo-Japanese War in 1905–1906 he served as a military doctor. Meanwhile, his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu) gained him some literary recognition.

In 1907–1908 Korczak went to study in Berlin. While working for the Orphan's Society in 1909 he met Stefania Wilczyńska, his future closest associate.[14] In 1911–1912 he became a director of Dom Sierot in Warsaw, the orphanage of his own design for Jewish children.[15] He hired Wilczyńska as his assistant. There he formed a kind-of-a-republic for children with its own small parliament, court, and a newspaper. He reduced his other duties as a doctor. Some of his descriptions of the summer camp for Jewish children in this period and subsequently, were later published in his Fragmenty Utworów and have been translated into English.

During World War I, in 1914 Korczak became a military doctor with the rank of Lieutenant. He served again as a military doctor in the Polish Army with the rank of Major during the Polish-Soviet War, but after a brief stint in Łódź was assigned to Warsaw. After the wars he continued his practice in Warsaw.

Sovereign Poland

In 1926 Korczak arranged for the children of the Dom Sierot to begin their own newspaper, the Mały Przegląd (Little Review), as a weekly attachment to the daily Polish-Jewish Newspaper Nasz Przegląd (Our Review). In these years, his secretary was the noted Polish novelist Igor Newerly.

During the 1930s he had his own radio program where he promoted and popularized the rights of children. In 1933 he was awarded the Silver Cross of the Polonia Restituta. Between 1934–36 Korczak traveled every year to Mandate Palestine and visited its kibbutzim, which led to some anti-semitic commentaries in the Polish press. Additionally, it spurred his estrangement with the non-Jewish orphanage he had also been working for. Still, he refused to move to Palestine even when Wilczyńska went to live there in 1938. She returned to Poland in May 1939, unable to fit in, and resumed her role of the Headmistress.[16]

The Holocaust

In 1939, when World War II erupted, Korczak volunteered for duty in the Polish Army but was refused due to his age. He witnessed the Wehrmacht takeover of Warsaw. When the Germans created the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, his orphanage was forced to move from its building, Dom Sierot at Krochmalna 92 to the Ghetto (first to Chłodna 33 and later to Sienna 16 / Śliska 9).[17] Korczak moved in with them. In July, Janusz Korczak decided that the children in the orphanage should put on Rabindranath Tagore’s play, The Post Office.

On 5 or 6 August 1942, German soldiers came to collect the 192 orphans (there is some debate about the actual number: it may have been 196), and about one dozen staff members, to transport them to Treblinka extermination camp. Korczak had been offered sanctuary on the “Aryan side” by Żegota but turned it down repeatedly, saying that he could not abandon his children. On 5 August he again refused offers of sanctuary, insisting that he would go with the children. He stayed with the children all the way until the end.

The children were dressed in their best clothes, and each carried a blue knapsack and a favorite book or toy. Joshua Perle, an eyewitness, described the procession of Korczak and the children through the ghetto to the Umschlagplatz (deportation point to the death camps):

Janusz Korczak was marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a child, without a hat, a leather belt around his waist, and wearing high boots. A few nurses were followed by two hundred children, dressed in clean and meticulously cared for clothes, as they were being carried to the altar.— Ghetto eyewitness, Joshua Perle[18]

According to a popular legend, when the group of orphans finally reached the Umschlagplatz, an SS officer recognized Korczak as the author of one of his favorite children's books and offered to help him escape. By another version, the officer was acting officially, as the Nazi authorities had in mind some kind of "special treatment" for Korczak (some prominent Jews with international reputations were sent to Theresienstadt). Whatever the offer, Korczak once again refused. He boarded the trains with the children and was never heard from again. Korczak's evacuation from the Ghetto is also mentioned in Władysław Szpilman's book The Pianist:

He told the orphans they were going out in to the country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange the horrible suffocating city walls for meadows of flowers, streams where they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms. He told them to wear their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely dressed and in a happy mood. The little column was led by an SS man...

Some time after, there were rumors that the trains had been diverted and that Korczak and the children had survived. There was, however, no basis to these stories. Most likely, Korczak, along with Wilczyńska and most of the children, was killed in a gas chamber upon their arrival at Treblinka. A differing account of Korczak's departure is given in Mary Berg's Warsaw Ghetto diary:

Dr. Janusz Korczak’s children’s home is empty now. A few days ago we all stood at the window and watched the Germans surround the houses. Rows of children, holding each other by their little hands, began to walk out of the doorway. There were tiny tots of two or three years among them, while the oldest ones were perhaps thirteen. Each child carried the little bundle in his hand.— Mary Berg, The Diary [20]

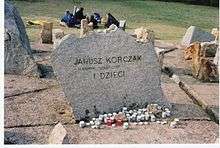

There is a cenotaph for him at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw, with a monumental sculpture of Korczak leading his children to the trains. Created originally by Mieczysław Smorczewski in 1982,[21] the monument was recast in bronze in 2002. The original was re-erected at the boarding school for children with special needs in Borzęciczki, which is named after Janusz Korczak.[22]

Writings

Korczak's best known writing is his fiction and pedagogy, and his most popular works have been widely translated. His main pedagogical texts have been translated into English, but of his fiction, as of 2012 only two of his novels have been translated into English: King Matt the First and Kaytek the Wizard.

As the date of Korczak's death was not officially established, his date of death for legal purposes was established in 1954 by a Polish court as 9 May 1946, a standard ruling for people whose death date was not documented but in all likelihood occurred during World War II. The copyright to all works by Korczak was subsequently acquired by The Polish Book Institute (Instytut Książki), a cultural institution and publishing house affiliated with the Polish government. In 2012 the Institute's right where challenged by the Modern Poland Foundation, whose goal was to establish by court trial that Korczak died in 1942, so that Korczak's works would be available in the Public domain as of 1 January 2013. The Foundation won the case in 2015 and subsequently started to digitize Korczak's works and release them as public domain e-books.[23][24][25]

Korczak's overall literary oeuvre covers the period 1896 to 8 August 1942. It comprises works for both children and adults, and includes literary pieces, social journalism, articles and pedagogical essays, together with some scrappy unpublished work, in all totaling over twenty books, over 1,400 texts published in around 100 publications, and around 300 texts in manuscript or typescript form. A complete edition of his works is planned for 2012.[26]

Children's books

Korczak often employed the form of the fairy tale in order to actually prepare his young readers for the dilemmas and difficulties of real adult life, and the need to make responsible decisions.

In the 1923 King Matt the First (Król Maciuś Pierwszy) and its sequel King Matt on the Desert Island (Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej) Korczak depicted a child prince who is catapulted to the throne by the sudden death of his father, and who must learn from various mistakes.

He tries to read and answer all his mail by himself and finds that the volume is too much and he needs to rely on secretaries; he is exasperated with his ministers and has them arrested, but soon realises that he does not know enough to govern by himself, and is forced to release the ministers and institute constitutional monarchy; when a war breaks out he does not accept being shut up in his palace, but slips away and joins up, pretending to be a peasant boy - and narrowly avoids becoming a POW; he takes the offer of a friendly journalist to publish for him a "royal paper" -and finds much later that he gets carefully edited news and that the journalist is covering up the gross corruption of the young king's best friend; he tries to organise the children of all the world to hold processions and demand their rights – and ends up antagonising other kings; he falls in love with a black African princess and outrages racist opinion (by modern standards, however, Korczak's depiction of blacks is itself not completely free of stereotypes which were current at the time of writing); finally, he is overthrown by the invasion of three foreign armies and exiled to a desert island, where he must come to terms with reality – and finally does.

Recently (2012), another book by Korczak was translated into English. Kajtuś the Wizard (Kajtuś czarodziej) (1933) anticipated Harry Potter in depicting a schoolboy who gains magic powers, and it was very popular during the 1930s, both in Polish and in translation to several other languages. Kajtuś has, however, a far more difficult path than Harry Potter: he has no Hogwarts-type School of Magic where he could be taught by expert mages, but must learn to use and control his powers all by himself - and most importantly, to learn his limitations.

Pedagogical books

In his pedagogical works, Korczak shares much of his experience dealing with difficult children. Korczak's ideas were further developed by many other pedagogues such as Simon Soloveychik and Erich Dauzenroth.

Thoughts on corporal punishment

Korczak spoke against corporal punishment of children at a time when such treatment was considered a parental entitlement or even duty. In The Child’s Right to Respect (1925), he wrote,

In what extraordinary circumstances would one dare to push, hit or tug an adult? And yet it is considered so routine and harmless to give a child a tap or stinging smack or to grab it by the arm. The feeling of powerlessness creates respect for power. Not only adults but anyone who is older and stronger can cruelly demonstrate their displeasure, back up their words with force, demand obedience and abuse the child without being punished. We set an example that fosters contempt for the weak. This is bad parenting and sets a bad precedent".[27]

List of selected works

Fiction

- Children of the Streets (Dzieci ulicy, Warsaw 1901)

- Fiddle-Faddle (Koszałki opałki, Warsaw 1905)

- Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu, Warsaw 1906, 2nd edition 1927) – partially autobiographical

- Mośki, Joski i Srule (Warsaw 1910)

- Józki, Jaśki i Franki (Warsaw 1911)

- Fame (Sława, Warsaw 1913, corrected 1935 and 1937)

- Bobo (Warsaw 1914)

- King Matt the First (Król Maciuś Pierwszy, Warsaw 1923) ISBN 1-56512-442-1

- King Matt on a Deserted Island (Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej, Warsaw 1923)

- Bankruptcy of Little Jack (Bankructwo małego Dżeka, Warsaw 1924)

- When I Am Little Again (Kiedy znów będę mały, Warsaw 1925)

- Senat szaleńców, humoreska ponura (Madmen's Senate, play premièred at the Ateneum Theatre in Warsaw, 1931)

- Kaytek the Wizard (Kajtuś czarodziej, Warsaw 1935)

Pedagogical books

- Momenty wychowawcze (Warsaw, 1919, 2nd edition 1924)

- How to Love a Child (Jak kochać dziecko, Warsaw 1919, 2nd edition 1920 as Jak kochać dzieci)

- The Child's Right to Respect (Prawo dziecka do szacunku, Warsaw, 1929)

- Playful pedagogy (Pedagogika żartobliwa, Warsaw, 1939)

Other books

- Diary (Pamiętnik, Warsaw, 1958)

- Fragmenty Utworów

- The Stubborn Boy: The Life of Pasteur (Warsaw, 1935)

In popular culture

In addition to theater, opera, TV, and film adaptations of his works, such as King Matt the First and Kaytek the Wizard, there have been a number of works about Korczak, inspired by him, or featuring him as a character.

Books:

- Milkweed by Jerry Spinelli (2003) – Doctor Korczak runs an orphanage in Warsaw where the main character often visits him

- Moshe en Reizele (Mosje and Reizele) by Karlijn Stoffels (2004) – Mosje is sent to live in Korczak's orphanage, where he falls in love with Reizele. Set in the period 1939-1942. Original Dutch, German translation available. No English version as of 2009.

- Once by Morris Gleitzman (2005), partly inspired by Korczak, featuring a character modeled after him

- Kindling by Alberto Valis (Felici Editori, 2011), Italian thriller novel. The life of Korczak through the voice of a Warsaw ghetto's orphan. As of 2011, no English translation.

- The Time Tunnel - Kingdom of the Children by Galila Ron-Feder-Amit (2007) is an Israeli children's book in the Time Tunnel series that takes place in Korczak's orphanage.

- The Book of Aron by Jim Shepherd (2015) is a fictional work that features Dr. Korczak and his orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto as main characters in the book.

Stage plays:

- Dr Korczak and the Children by Erwin Sylvanus (1957)

- Korczak's Children by Jeffrey Hatcher (2003)

- Dr Korczak's Example by David Greig (2001)[28]

- The Children's Republic A play based on the life and work of Yanusz Korczak (2008) by Elena Khalitov, Harmony Theatre Company and School

- The Children's Republic by Hannah Moscovitch (2009)

- "Loving Every Child: Wisdom for Parents" Edited by [Sandra Joseph] korczak.org.uk

Musicals:

- Facing the wall - Janusz Korczak by Klaus-Peter Rex and Daniel Hoffmann (1997) presented by Music-theatre fuenf brote und zwei fische, Wülfrath

- Korczak by Nick Stimson and Chris Williams (2011) presented by Youth Music Theatre: UK at the Rose Theatre, Kingston in August 2011.

Film:

- Sie sind frei, Dr. Korczak (The Martyr), written by Ben Barzman and Alexander Ramati, directed by Aleksander Ford (1975)

- Korczak, written by Agnieszka Holland, directed by Andrzej Wajda (1990)

- Uprising (2001) directed by Jon Avnet, written by Avnet and Paul Brickman. Palle Granditsky portrayed Korczak.

Television:

- Studio 4: Dr Korczak and the Children - BBC adaptation of Sylvanus's play, written and directed by Rudolph Cartier (13 March 1962)

Music:

- Korczak's Orphans – opera, music by Adam Silverman, libretto by Susan Gubernat (2003)

- Kaddish – long poem/song by Alexander Galich (1970)

- King Mattias I - opera, music by Viggo Edén, from writings by Korczak, given World Premiere at Höör's Summer Opera (Sweden) on 9 August 2012.

- 'The Little Review' from album 'Where the Darkness Goes', Awna Teixeira, 2012

- Janusz - piece for piano, music by Nicola Gelo (2013)

Astronomy:

- Asteroid 2163 Korczak is named in his honor.

Notes

- ↑ Korczak himself was unsure of his birth date, which he attributed to his father's failure to promptly acquire a birth certificate for him.[4]

References

- 1 2 Yad Vashem (2010). "Ceremony Marking 68 Years Since its Murder of Korczak and the Children of the Orphanage". Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "Jewish Doctor Janusz Korczak Died With 190 Children at Treblinka Court: Changes Date of Death for Orphanage Director". JTA. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Sandra Joseph, Institute of Education in London (July–August 2002). "POLE APART - the life and work of Janusz Korczak". Young Minds Magazine 59. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Polskie Stowarzyszenie im. Janusza Korczaka". www.pskorczak.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ Tadeusz Lewowicki (2000). "Janusz Korczak (1878–1942)" (PDF, 43 KB). Prospects:the quarterly review of comparative education, vol. XXIV, no. 1/2, 1994, p. 37–48. UNESCO: International Bureau of Education. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- 1 2 Prof. Barbara Smolińska–Theiss (2012). "Janusz Korczak – zarys portretu (the portrait)" (in Polish). Rok Janusza Korczaka (The official year of Janusz Korczak). Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ The Month, Volume 39. Simpki, Marshall, and Company. 1968. p. 350.

When Dr. Janusz Korczak, a Jewish philanthropist and agnostic, voluntarily chooses to follow the Jewish orphans under his care to the Nazi extermination camp in Treblinka...

- ↑ Chris Mullen (March 7, 1983). "Korczak's Children: Flawed Faces in a Warsaw Ghetto". The Heights. p. 24. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

An assimilated Jew, he changed his name from Henryk Goldschmidt and was an agnostic who did not believe in forcing religion on children.

- ↑ Janusz Korczak (1978). Ghetto diary. Holocaust Library. p. 42.

You know I am an agnostic, but I understood: Pedagogy, tolerance, and all that.

- ↑ Janusz Korczak; Aleksander Lewin (1996). Sława: Opowiadania (1898-1914) (in Polish). Oficyna Wydawnicza Latona. p. 387. ISBN 978-83-85449-35-5.

- ↑ Maria Falkowska (1978). Kalendarium życia, działalności i twórczości Janusza Korczaka (in Polish). Wydaw-a Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. p. 8.

- 1 2 Joanna Cieśla (15 January 2012). "Henryk zwany Januszem. Janusz Korczak - pedagog rewolucjonista" (in Polish). S.P. Polityka. Historia. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (2012). "Moja Biblioteczka". Historia o Janaszu Korczaku i o pięknej Miecznikównie. LubimyCzytać.pl. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Carrie-Anne (2006). "Stefania Wilczyńska (1886–August 6, 1942)". Biography and photographs. Findagrave.com. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Hanna Mortkowicz-Olczakowa (1960). "Goldszmit Henryk", in Polski Słownik Biograficzny, T. VIII. P. 214

- ↑ Agnieszka Litwiniuk (March 29, 2012). "Stefania Wilczyńska". Sylwetki warszawskich Żydówek (Profiles of Warsaw Jewish women) (in Polish). Warszefroj, Centrum Kultury Jidysz (Yidish Centre). Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Dom Sierot. Krochmalna 92". Swedish Holocaust Memorial Association. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Nick Shepley (7 December 2015). Hitler, Stalin and the Destruction of Poland: Explaining History. Andrews UK Limited. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-78333-143-7.

- ↑ Jerzy Waldorff, Władysław Szpilman, The Pianist. Page 96.

- ↑ Mary Berg, The Diary of Mary Berg: Growing Up in the Warsaw Ghetto, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1996, pages 169-170.

- ↑ "The Jewish Cemetery on Okopowa Street in Warsaw (Cmentarz żydowski przy ul. Okopowej w Warszawie)". Cmentarium. 2007. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ↑ Mirosław Gorzelanny (November 27, 2012). "School history". Specjalny Ośrodek Szkolno – Wychowawczy im Janusza Korczaka w Borzęciczkach. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Wyrok w sprawie Korczaka – omówienie". Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Wygrany spór o datę śmierci Korczaka. Prawda pokonała "własność intelektualną"". Dziennik Internautów. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Author: Janusz Korczak". Wolne Lektury. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Janusz Korczak", Book Institute

- ↑ Modig, Cecilia (2009). Never Violence – Thirty Years on from Sweden's Abolition of Corporal Punishment (PDF). Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden; Save the Children Sweden. Reference No. S2009.030. p. 8.

- ↑ Hickling, Alfred (June 12, 2008). "?". The Guardian. London.

Further reading

- Bystrzycka, Anna (July 2007). "Dzieci z sierocińca". Zwrot: 30–31.

- Cohen, Adir (1994). The Gate of Light: Janusz Korczak, the Educator and Writer who Overcame the Holocaust. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-838-63523-0.

- Joseph, Sandra (1999). A Voice for the Child: The inspirational words of Janusz Korczak. Collins Publishers.

- Lifton, Betty Jean (1988). The King of Children: The Life and Death of Janusz Korczak Collins Publishers.

- Mortkowicz-Olczakowa, Hanna (1961). Bunt wspomnień. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Parenting Advice from a Polish Holocaust Hero from National Public Radio

- Lawrence Kohlberg (1981). The Philosophy of Moral Development: Education for Justice pp. 401–408. Harper & Row, Publishers, San Francisco.

- Mark Celinscak (2009). “A Procession of Shadows: Examining Warsaw Ghetto Testimony.” New School Psychology Bulletin. Volume 6, Number 2: 38-50.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Janusz Korczak. |

| Polish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Janusz Korczak Living Heritage Association

- Ojemba Productions presents 'KORCZAK' at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2005!

- Korczak's Orphans opera by Adam Silverman and Susan Gubernat

- I'm small, but important, German Documentary by Walther Petri and Konrad Weiss

- Wiersz Kazimierza Dąbrowskiego "Wątek X - Janusz Korczak" Heksis 1/2010

- Janusz Korczak at culture.pl

- 2012 - The Year of Janusz Korczak