Jean Giraud

| Jean Giraud | |

|---|---|

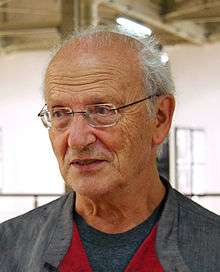

Jean Giraud at the International Festival of Comics in Łódź, 4 October 2008. | |

| Born |

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud 8 May 1938 Nogent-sur-Marne, France |

| Died |

10 March 2012 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Area(s) | Writer, Artist |

| Pseudonym(s) | Mœbius, Gir |

Notable works | |

Notable collaborations | Alejandro Jodorowsky, Jean-Michel Charlier |

| Awards | full list |

| Spouse(s) |

Claudine Conin (m. 1967–94) Isabelle Champeval (m. 1995–2012) |

| Children | fr:Hélène Giraud (1970), Julien Giraud (1972), Raphaël Giraud (1997), Nausicaa Giraud |

| Signature | |

|

| |

|

moebius | |

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud (French: [ʒiʁo]; 8 May 1938 – 10 March 2012) was a French artist, cartoonist and writer who worked in the Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées tradition. Giraud garnered worldwide acclaim predominantly under the pseudonym Mœbius and to a lesser extent Gir, which he used for the Blueberry series and his paintings. Esteemed by Federico Fellini, Stan Lee and Hayao Miyazaki among others,[1] he has been described as the most influential bandes dessinées artist after Hergé.[2]

His most famous works include the series Blueberry, created with writer Jean-Michel Charlier, featuring one of the first anti-heroes in Western comics. As Mœbius he created a wide range of science fiction and fantasy comics in a highly imaginative, surreal, almost abstract style. These works include Arzach and the Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius. He also collaborated with avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky for an unproduced adaptation of Dune and the comic book series The Incal.

Mœbius also contributed storyboards and concept designs to numerous science fiction and fantasy films, such as Alien, Tron, The Fifth Element and The Abyss. In 2004,[3] Moebius and Jodorowsky sued Luc Besson for using The Incal as inspiration for Fifth Element, a lawsuit which they lost.[4] Blueberry was adapted for the screen in 2004 by French director Jan Kounen.

Early life

Jean Giraud was born in Nogent-sur-Marne, Val-de-Marne, in the suburbs of Paris, on 8 May 1938,[5][6] as the only child to Raymond Giraud, an insurance agent, and Pauline Vinchon who had worked at the agency.[7] When he was three years old, his parents divorced and he was raised mainly by his grandparents, who were living in the neighboring municipality of Fontenay-sous-Bois (much later, when he was the acclaimed artist, Giraud returned to live in the municipality in the mid-1970s, but was regrettably unable to buy his grandparents house[8]). The rupture between mother and father created a lasting trauma that he explained lay at the heart of his choice of separate pen names.[9] An introverted and somewhat sickly child at first, the latter resulting from the poor food situation in German occupied France during World War II, young Giraud found solace after the war in a small theater, located on a corner in the street where his grandparents lived, which concurrently provided an escape from the dreary atmosphere in post-war reconstruction era France. Playing an abundance of American B-Westerns, it was there that Giraud, frequenting the theater as often as he was able to, developed a passion for the genre, as had so many other European boys his age in those times.[8] In 1954 at age 16,[10] he began his only technical training at the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré, where he, unsurprisingly, started producing Western comics, which however did not sit well with his teachers.[11] He became close friends with another comic artist, Jean-Claude Mézières, in no small part due to their shared passion for Westerns and the Far West. In 1956 he left art school without graduating to visit his mother, who had married a Mexican in Mexico, and stayed there for eight months.

It was the experience of the Mexican desert, in particular its endless blue skies and unending flat plains, now seeing and experiencing for himself the vistas that had enthralled him so much when watching westerns on the silver screen only a few years earlier, which left an everlasting, "quelque chose qui m'a littéralement craqué l'âme",[12] enduring impression on him, easily recognizable in almost all of his later seminal works.[13] After his return to France, he started to work as a full-time artist.[14] In 1959–1960 he was slated for military service in Algeria,[15] in the throes of the vicious Algerian War at the time, but fortunately for him, ended up serving out his military obligations in the French occupation zone of Germany where he collaborated on the army magazine 5/5 Forces Françaises.[8]

Career

Western comics

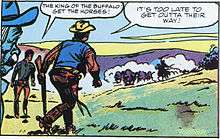

At 18, Giraud was drawing his own comic Western strip, "Frank et Jeremie", for the magazine Far West, his very first commercial sale. From 1956 to 1958 he published Western comics, alongside several others of a French historical nature, in the magazines "Fripounet et Marisette", "fr:Cœurs Valiants" and "Ames Valliantes" – all from catholic publisher Fleurus, and all of them of a strong edifying nature aimed at France's adolescent youth – , among them a strip called "King of the Buffalo", and another called "A Giant with the Hurons".[16] It was for Fleurus that Giraud also illustrated his first three books.[17] Already in this period his style was heavily influenced by his later mentor, Joseph "Jijé" Gillain.[14] In 1961, returning from military service in Germany (where he, being the only service man available with a graphics background, was set to work as illustrator on 5/5 Forces Françaises), Giraud became an apprentice of Jijé, who was one of the leading comic artists in Europe of the time. For Jijé, Giraud created several other shorts and illustrations for the short-lived magazine Bonux-Boy (1960/61), his first work after military service, and his last before embarking on Blueberry.[18] In his period, Jijé used Giraud as his assistant on an album of his Western series Jerry Spring, "The Road to Coronado", which Giraud inked.[15]

In 1962, Giraud and writer Jean-Michel Charlier started the comic strip Fort Navajo for Pilote magazine no. 210. At this time affinity between the styles of Giraud and Jijé (who actually had been Charlier's first choice for the series, but who was reverted to Giraud by Jijé) was so close that Jijé penciled several pages for the series, when Giraud went AWOL on two occasions; the first time during the production of "Thunder in the West" (1964) when he still inexperienced Giraud, buckling under the stress of having to produce a strictly scheduled magazine serial, suffered from a nervous breakdown, with Jijé taking on plates 28–36.[19] The second time occurred one year later, during the production of "Mission to Mexico (The Lost Rider)", when Giraud unexpectedly packed up and left to travel the United States,[20]and, again, Mexico; yet again former mentor Jijé came to the rescue by penciling plates 17–38.[21][22] Had the art style of both artists been nearly indistinguishable from each other in "Thunder in the West", after Giraud resumed work on plate 39 of "Mission to Mexico", a clearly noticeable style breach was this time observable, indicating that Giraud was now well on his way to develop his own signature style, eventually surpassing that of his former teacher Jijé.

The Lieutenant Blueberry character, whose facial features were based on those of the actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, was created in 1963 by Charlier (scenario) and Giraud (drawings) for Pilote magazine[23][24] and, while the Fort Navajo series had had originally been intended as an ensemble narrative, it quickly gravitated towards Blueberry as its most popular figure. His adventures featured in, what was later re-coined, the Blueberry series (usually encompassing multi-volume story lines) may be Giraud's work best known in his native France and the rest of Europe, before later collaborations with Alejandro Jodorowsky. The early Blueberry comics used a simple line drawing style similar to that of Jijé, and standard Western themes and imagery (specifically, those of John Ford's US Cavalry Western trilogy, with Howard Hawk's 1959 Rio Bravo thrown in for good measure for the sixth, one-shot title "The Man with the Silver Star"), but gradually Giraud developed a darker and grittier style inspired by, firstly the 1970 Westerns Soldier Blue and Little Big Man (for the "Iron Horse" saga), and subsequently by the Spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone and the dark realism of Sam Peckinpah in particular (for the "Lost Goldmine" saga and beyond).[25] With the fifth album, "The Trail of the Navajos", Giraud established his own style, and after censorship laws were loosened in 1968 the strip became more explicitly adult, and also adopted a wider range of thematics.[2][22] The first Blueberry album penciled by Giraud after he had begun publishing science fiction as Mœbius, "Broken Nose", was much more experimental than his previous Western work.[22]

Giraud left the series in 1974, partly because he was tired of the publication pressure he was under in order to produce the series, partly because of an emerging royalties conflict, but mostly because he wanted further explore and develop his "Mœbius" alter ego, the work he produced as such being published in the by him co-founded Métal hurlant magazine, in the process revolutionizing the Franco-Belgian comic world. He returned to the series in 1979.

In 1979, the long-running disagreement Charlier and Giraud had a with their publishing house Dargaud over the publishing residuals from Blueberry, came to a head. Instead they began the western comic Jim Cutlass as a means to put the pressure on Dargaud. It did not work, and Charlier and Giraud turned their back on the parent publisher, leaving for greener pastures elsewhere, and in the process taking all of Charlier's co-creations with them. It would take nearly fifteen years before the Blueberry series returned to the parent publisher after Charlier died. After the first album, "Mississippi River", first serialized in Métal Hurlant Giraud took on scripting the series years later, but left the artwork to Christian Rossi.[26]

When Charlier, Giraud's collaborator on Blueberry, died in 1989, Giraud assumed responsibility for the scripting of the main series. Blueberry has been translated into 19 languages, the first English book translations being published in 1977/78 by UK publisher Egmont/Methuen. The original Blueberry series has spun off a prequel series called "Young Blueberry", but left the artwork to Colin Wilson and later Michel Blanc-Dumont after volume three in that series, as well as an intermezzo called "Marshall Blueberry".[23]

Science fiction and fantasy comics

The Mœbius pseudonym, which Giraud came to use for his science fiction and fantasy work, was born in 1963.[15] In a satire magazine called Hara-Kiri, Giraud used the name for 21 strips in 1963–64. Subsequently, the pseudonym went unused for a decade.

In 1975 he revived the Mœbius pseudonym, and with Jean-Pierre Dionnet, Philippe Druillet and Bernard Farkas, he became one of the founding members of the comics art group "Les Humanoïdes Associés".[27] Together they started the magazine Métal hurlant,[28] and for which he had temporarily abandoned his Blueberry series. The magazine known in the English-speaking world as Heavy Metal. Mœbius' famous serial The Airtight Garage and his groundbreaking Arzach both began in Métal hurlant.[29] In 1976, Métal hurlant published "The Long Tomorrow", written by Dan O'Bannon.

Arzach is a wordless comic, created in a conscious attempt to breathe new life into the comic genre which at the time was dominated by American superhero comics. It tracks the journey of the title character flying on the back of his pterodactyl through a fantastic world mixing medieval fantasy with futurism. Unlike most science fiction comics, it has no captions, no speech balloons and no written sound effects. It has been argued that the wordlessness provides the strip with a sense of timelessness, setting up Arzach's journey as a quest for eternal, universal truths.[1]

His series The Airtight Garage is particularly notable for its non-linear plot, where movement and temporality can be traced in multiple directions depending on the readers own interpretation even within a single planche (page or picture). The series tells of Major Grubert, who is constructing his own universe on an Asteroid named fleur, where he encounters a wealth of fantastic characters including Michael Moorcock's creation Jerry Cornelius.[30]

In 1980 he started his famous L'Incal series in collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky. From 1985 to 2001 he also created his six-volume fantasy series Le Monde d'Edena, portions of which appeared in English as The Aedena Cycle. The stories were strongly influenced by the teachings of Jean-Paul Appel-Guéry.[lower-alpha 1]

In his later life, Giraud decided to revive the Arzak character in an elaborate new adventure series; the first volume of a planned trilogy, Arzak l'arpenteur, appeared in 2010. He also added to the Airtight Garage series with a new volume entitled Le chasseur déprime.

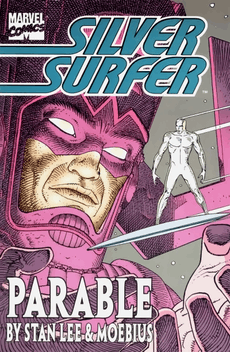

Marvel Comics

A two-issue Silver Surfer miniseries (later collected as Silver Surfer: Parable), written by Stan Lee and drawn by Giraud (as Mœbius), was published through Marvel's Epic Comics imprint in 1988 and 1989. According to Giraud, this was his first time working under the Marvel method instead of from a full script.[28] This miniseries won the Eisner Award for best finite/limited series in 1989.

Other work

From 2000 to 2010, Giraud published Inside Mœbius (French text despite English title), an illustrated autobiographical fantasy in six hardcover volumes totaling 700 pages.[9] Pirandello-like, he appears in cartoon form as both creator and protagonist trapped within the story alongside his younger self and several longtime characters such as Blueberry, Arzak (the latest re-spelling of the Arzach character's name), Major Grubert (from The Airtight Garage) and others.

Jean Giraud drew the first of the two-part volume of the XIII series titled La Version Irlandaise ("The Irish Version") from a script by Jean Van Hamme, to accompany the second part by the regular team Jean Van Hamme–William Vance, Le dernier round ("The Last Round"). Both parts were published on the same date (13 November 2007)[31] and were the last ones written by Van Hamme before Yves Sentes took over the series.[32] Vance incidentally, had previously provided the artwork for the first two titles in the Marshall Blueberry spin-off series.

Illustrator and author

Under the names Giraud and Gir, he also wrote numerous comics for other comic artists like Auclair and Tardi. He also made illustrations for books and magazines, illustrating for example one edition of the novel The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho.

Films

As Mœbius, Giraud contributed storyboards and concept designs to numerous science fiction films, including Alien by Ridley Scott, Tron by Disney, The Fifth Element by Luc Besson, Star Wars Episode V and for Jodorowsky's planned adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, which was however abandoned in pre-production.[33] Jodorowsky's Dune, a 2013 American-French documentary directed by Frank Pavich, explores Jodorowsky's unsuccessful attempt.

In 1982 he collaborated with director René Laloux to create the science fiction feature-length animated movie Les Maîtres du temps (released in English as Time Masters) based on a novel by Stefan Wul. He and director Rene Laloux shared the award for Best Children's Film at the Fantafestival that year.[34]

With Yutaka Fujioka, he wrote the story for the 1989 Japanese animated feature film Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland; as well, he was a conceptual designer for the movie.[34]

Giraud made original character designs and did visual development for Warner Bros. partly animated 1996 movie Space Jam. And, though uncredited, he provided characters and situations for the "Taarna" segment of Ivan Reitman's 1981 film Heavy Metal.[34]

In 1991 his graphic novel Cauchemar Blanc was cinematized by Matthieu Kassovitz. The Blueberry series was adapted for the screen in 2004, by Jan Kounen, as Blueberry: L'expérience secrète. Two previous attempts to bring Blueberry to the silver screen in the 1980s had fallen through; American actor Martin Kove had actually already been signed to play the titular role for one of the attempts.[35]

2005 saw the release of the Chinese movie Thru the Moebius Strip, based on a story by Giraud who also served as the production designer.

Exhibitions

From December 2004 to March 2005, his work was exhibited with that of Hayao Miyazaki at La Monnaie in Paris.[36]

From 12 October 2010 to 13 March 2011, the Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain presented the exhibition MOEBIUS-TRANSE-FORME, which the museum called "the first major exhibition in Paris devoted to the work of Jean Giraud, known by his pseudonyms Gir and Mœbius."[37] A prestigious event, it reflected the status Giraud has attained in French (comic) culture.

Stamps

In 1988 Giraud was chosen, among 11 other winners of the prestigious Grand Prix of the Angoulême Festival, to illustrate a postage stamp set issued on the theme of communication.[38]

Style

Giraud's working methods were various and adaptable ranging from etchings, white and black illustrations, to work in colour of the ligne claire genre and water colours.[39] Giraud's solo Blueberry works were sometimes criticized by fans of the series because the artist dramatically changed the tone of the series as well as the graphic style.[40] However, Blueberry's early success was also due to Giraud's innovations, as he did not content himself with following earlier styles, an important aspect of his development as an artist.[41]

To distinguish between work by Giraud and Moebius, Giraud used a brush for his own work and a pen when he signed his work as Moebius. Giraud drew very quickly.[42]

His style has been compared to the Nouveaux réalistes, exemplified in his turn from the bowdlerized realism of Hergé's Tintin towards a grittier style depicting sex, violence and moral bankruptcy.[1]

Throughout his career he used drugs and cultivated various New Age type philosophies, such as Guy-Claude Burger's instinctotherapy, which influenced his creation of the comic book series Le Monde d'Edena.[1][9] However, it also negatively influenced his relationship with Philippe Charlier, heir and steward of his father's Blueberry co-creation and legacy, who had no patience whatsoever with Giraud's New Age predilections, particularly for his admitted fondness for mind-expanding substances. Charlier jr. has vetoed several later Blueberry project proposals by Giraud, the Blueberry 1900 project in particular, precisely for these reasons, as they were to prominently feature substance induced scenes.[43]

Death

Giraud died in Paris, on 10 March 2012, aged 73, after a long battle with cancer.[44][45][46][47] The immediate cause of death was pulmonary embolism caused by a lymphoma. Mœbius was buried on 15 March, in the Montparnasse Cemetery.[48] Fellow comic artist François Boucq (incidentally, the artist pegged by Giraud in person for the artwork of the canceled Blueberry 1900 project) stated that Mœbius was a "master of realist drawing with a real talent for humour, which he was still demonstrating with the nurses when I saw him in his hospital bed a fortnight ago".[49]

Influence and legacy

Many artists from around the world have cited Giraud as an influence on their work. Giraud was longtime friends with manga author and anime filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. Giraud even named his daughter Nausicaä after the character in Miyazaki's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.[50][51] Asked by Giraud in an interview how he first discovered his work, Miyazaki replied:

Through Arzach, which dates from 1975, I believe. I only read it in 1980, and it was a big shock. Not only for me. All manga authors were shaken by this work. Unfortunately, when I discovered it, I already had a consolidated style so I couldn't use its influence to enrich my drawing. Even today, I think it has an awesome sense of space. I directed Nausicaä under Mœbius's influence.[52][53]

Pioneering cyberpunk author William Gibson said of Giraud's work "The Long Tomorrow":

So it's entirely fair to say, and I've said it before, that the way Neuromancer-the-novel "looks" was influenced in large part by some of the artwork I saw in Heavy Metal. I assume that this must also be true of John Carpenter's Escape from New York, Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, and all other artefacts of the style sometimes dubbed 'cyberpunk'. Those French guys, they got their end in early.[54]

"The Long Tomorrow" also came to the attention of Ridley Scott and was a key visual reference for Blade Runner.[54]

"I consider him more important than Doré", said Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini:

"He's a unique talent endowed with an extraordinary visionary imagination that's constantly renewed and never vulgar. Moebius disturbs and consoles. He has the ability to transport us into unknown worlds where we encounter unsettling characters. My admiration for him is total. I consider him a great artist, as great as Picasso and Matisse."[55]

Following his death, Brazilian author Paulo Coelho paid tribute on Twitter stating:

"The great Moebius died today, but the great Mœbius is still alive. Your body died today, your work is more alive than ever."[49]

Benoît Mouchart, artistic director at France's Angoulême International Comics Festival, made an assessment of his importance to the field of comics:

"France has lost one of its best known artists in the world. In Japan, Italy, in the United States he is an incredible star who influenced world comics. Mœbius will remain part of the history of drawing, in the same right as Dürer or Ingres. He was an incredible producer, he said he wanted to show what eyes do not always see".[49]

French Culture Minister Frédéric Mitterrand said that by the simultaneous death of Giraud and Mœbius, France had lost "two great artists".[49]

Awards

- 1973: Shazam Award, Best Foreign Comic Series, for Lieutenant Blueberry

- 1975: Yellow Kid Award, Lucca, Italy, Best Foreign Artist[56]

- 1977: Angoulême International Comics Festival Best French Artist

- 1979: Adamson Award, for Lieutenant Blueberry etc.

- 1980: Yellow Kid Award, Lucca, Italy, Best Foreign Author[57]

- 1980: Grand Prix de la Science Fiction Française, Special Prize, for Major Fatal[58]

- 1981: Angoulême International Comics Festival Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême

- 1985: Angoulême International Comics Festival Grand Prix for the graphic arts

- 1986: Inkpot Award

- 1988: Harvey Award, Best American Edition of Foreign Material, for Moebius album series

- 1989: Eisner Award, Best Finite Series, for Silver Surfer

- 1989: Harvey Award, Best American Edition of Foreign Material, for Incal

- 1991: Eisner Award, Best Single Issue, for Concrete

- 1991: Harvey Award, Best American Edition of Foreign Material, for Lieutenant Blueberry

- 1997: Designated finalist for induction into the Harvey Award Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1989, inducted in 1997

- 1997: World Fantasy Award for Best Artist[59]

- 1998: Included in the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame

- 2000: Max & Moritz Prizes, Special Prize for outstanding life's work

- 2001: Haxtur Award Best Long Comic Strip, for The Crowned Heart

- 2001: Spectrum Grandmaster[59]

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame inducted Jean Giraud in 2011.[59][60]

Bibliography

Those works for which English translations have been published are noted as such. Their respective pages describe this further.

As Jean Giraud

- Blueberry (29 volumes, English translation, 1965 – ), artist (all vol), writer vol 25–29

- Jim Cutlass (7 volumes, 1979–1999), artist vol. 1, writer vol 2–7 (artist: Christian Rossi)

- XIII (volume 18, La Version irlandaise in 2007), artist

- Marshall Blueberry (3 volumes, 2000), writer

- Le Cristal Majeur (7 volumes, 1986–2003), artist (writer: Marc Bati), Paris: Dargaud

As Mœbius

- Le Bandard fou (English translation, 1975), writer and artist

- Arzach (English translation, 1976), writer and artist

- "The Long Tomorrow" (originally in English, 1976), artist

- L'Homme est-il bon? (English translation, 1977), writer and artist

- Le Garage Hermétique (The Airtight Garage, English translation, 1976–1980), writer and artist

- Les Yeux du Chat (1978), artist

- Tueur de monde (1979), writer and artist

- l'Incal (The Incal, 6 volumes, English translation, 1981–1988), artist

- Les Maîtres du temps (1982), artist

- Venise céleste (1984), writer and artist

- Le Monde d'Edena (6 volumes, 1985–2001), writer and artist

- Silver Surfer: Parable (Originally in English, 1988–1989), artist

- Escale sur Pharagonescia (1989), writer and artist

- Les Vacances du Major (1992), writer and artist

- Le Cœur couronné (The Crowned Heart, English translation, 1992), artist

- Les Histoires de Monsieur Mouche (1994), artist

- Griffes d'Ange (1994), artist

- Little Nemo (1994), writer

- Ballades (1 volume, 1995), artist

- L'Homme du Ciguri (1995), writer and artist

- 40 Days dans le Désert B (1999), writer and artist

- Après l'Incal (2000 – ), artist

- Inside Mœbius (6 volumes, 2000–2010), writer and artist

- Icare (2005), writer

- The Halo Graphic Novel (originally in English, 2006), artist

- Le Chasseur Déprime (2008), writer and artist

- Arzak L'Arpenteur (2010), writer and artist

- La Faune de Mars (2011), writer and artist

- Le Major (2011), writer and artist

Collected editions

The English-language versions of many of Mœbius's comics have been collected into various editions, beginning with a series of trade paperbacks from Marvel Comics' Epic imprint in the late 1980s and early 1990s, translated and introduced by Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier:

The Collected Fantasies of Jean Giraud (1987–1994):

- Moebius 0 – The Horny Goof & Other Underground Stories (72 pages, Dark Horse, 1990, ISBN 1-878574-16-7)

- Moebius ½ – The Early Moebius & Other Humorous Stories (Graphitti Designs, 1992, ISBN 0-936211-28-8)

- Moebius 1 – Upon A Star (72 pages, Marvel/Epic, 1987, ISBN 0-87135-278-8)

- Moebius 2 – Arzach & Other Fantasy Stories (72 pages, Titan, ISBN 1-85286-045-6, Marvel/Epic, 1987)

- Moebius 3 – The Airtight Garage (120 pages, Titan, ISBN 1-85286-046-4, Marvel/Epic, 1987)

- Moebius 4 – The Long Tomorrow & Other Science Fiction Stories (70 pages, Marvel/Epic, 1987, ISBN 0-87135-281-8)

- Moebius 5 – The Gardens of Aedena (72 pages, Titan, ISBN 1-85286-047-2, Marvel/Epic, 1988, ISBN 0-87135-282-6)

- Moebius 6 – Pharagonesia & Other Strange Stories (72 pages, Titan, ISBN 1-85286-048-0, Marvel/Epic, 1988)

- Moebius 7 – The Goddess (88 pages, Marvel/Epic, 1990, ISBN 0-87135-714-3)

- Moebius 8 – Mississippi River (64 pages, Marvel/Epic, 1991, ISBN 0-87135-715-1)

- Moebius 9 – Stel (Marvel/Epic, 1994)

Excepting Moebius 9, these volumes were very shortly thereafter reissued by Graphitti Designs as a series of signed and numbered to 1500 copies, hardcover limited editions, combining these with the similar Blueberry releases by Epic, in a single "Mœbius", complete works, nine-volume anthology collection.

In 2010 and 2011, the publisher Humanoids (in the U.S.) began releasing new editions of Mœbius works, starting with three of Mœbius's past collaborations with Alejandro Jodorowsky: The Incal (original series complete in one volume), Madwoman of the Sacred Heart (all three parts complete in one volume) and The Eyes of the Cat.

Filmography

- Alien (1979)

- The Time Masters (1982)

- Tron (1982)

- Masters of the Universe (1987)

- Willow (1988)

- The Abyss (1989)

- Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989)

- The Fifth Element (1997) – The production design for the film was developed by Giraud and Jean-Claude Mézières.

- Fellini: I'm a Born Liar (2002) – Giraud conceived the poster for the documentary's 2003 North American release and appears in the DVD bonus extras of the French version.

- Blueberry (2004) – On the DVD extras Giraud talks about the comic, the film etc., dressed in period costume.

- Thru the Moebius Strip (2005)

- Strange frame (2009)

Video games

- Fade to Black cover art (1995)

- Panzer Dragoon (1995)

- Pilgrim: Faith as a Weapon (1998)

- An arcade and bar based on Giraud's work, called The Airtight Garage, was one of the original main attractions at the Metreon in San Francisco when the complex opened in 1999. It included three original games: Quaternia, a first-person shooter networked between terminals and based on the concept of "junctors" from Major Fatal and The Airtight Garage; a virtual reality bumper cars game about mining asteroids; and Hyperbowl, an obstacle course bowling game incorporating very little overtly Moebius imagery. The arcade was closed and reopened as "Portal One", retaining much of the Moebius-based decor and Hyperbowl but eliminating the other originals in favor of more common arcade games.

- Jet Set Radio Future inspired the artwork and graphics of the game (2002)

- Seven Samurai 20XX character design (2004)

- Gravity Rush inspired the artwork and graphics of the game

Documentaries

- The Masters of Comic Book Art – Documentary by Ken Viola (USA, 1987, 60 min.)

- La Constellation Jodorowsky – Documentary by Louis Mouchet. Giraud and Alejandro Jodorowsky on The Incal and their abandoned film adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune. During the psycho-genealogical session that concludes the film, Giraud impersonates Mouchet's father (Switzerland, 1994, 88 min. and 52 min.)

- Mister Gir & Mike S. Blueberry – Documentary by Damian Pettigrew. Giraud executes numerous sketches and watercolors for the Blueberry album, "Géronimo l'Apache", travels to Saint Malo for the celebrated comic-book festival, visits his Paris editor Dargaud, and in the film's last sequence, does a spontaneous life-size portrait in real time of Geronimo on a large sheet of glass (France, 2000: Musée de la Bande dessinée d'Angoulême, 55 min.)

- Moebius Redux: A Life in Pictures – Biographical documentary by Hasko Baumann (Germany, England, Finland, 2007: Arte, BBC, ZDF, YLE, 68 min.)

- Jean Van Hamme, William Vance et Jean Giraud à l'Abbaye de l'Épau – Institutional documentary (France, 2007: FGBL Audiovisuel, 70 min.)

- Métamoebius – Autobiographical portrait co-written by Jean Giraud and directed by Damian Pettigrew for the 2010 retrospective held at the Fondation Cartier for Contemporary Art in Paris (France, 2010: Fondation Cartier, CinéCinéma, 72 min. and 52 min.)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Appel-Guéry encouraged Moebius to tap into the more positive zones of his subconscious. 'Most of the people that were studying spirituality with Appel-Guéry did not know much about comics, but they immediately picked on the morbid, and overall negative feelings that permeated my work,' said Moebius. 'So I began to feel ashamed, and I decided to do something really different, just to show them that I could do it.'"[61]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Screech, Matthew. 2005. Moebius/Jean Giraud: Nouveau Réalisme and Science fiction. in Libbie McQuillan (ed) "The Francophone bande dessinée" Rodopi. p. 1

- 1 2 Screech, Matthew. 2005. "A challenge to Convention: Jean Giraud/Gir/Moebius" Chapter 4 in Masters of the ninth art: bandes dessinées and Franco-Belgian identity. Liverpool University Press. pp 95 – 128

- ↑ [Archived index at the Wayback Machine. "Moebius perd son procès contre Besson"] Check

|url=value (help). toutenbd.com. 28 May 2004. - ↑ "Moebius perd son procès contre Besson". ToutenBD.com (in French). 28 May 2004. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ↑ Comics Buyer's Guide #1485; 3 May 2002; Page 29

- ↑ De Weyer, Geert (2008). 100 stripklassiekers die niet in je boekenkast mogen ontbreken (in Dutch). Amsterdam / Antwerp: Atlas. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-450-0996-4.

- ↑ https://www.whoswho.fr/decede/biographie-m%C5%93bius_42760

- 1 2 3 Giraud has discussed his early life at length throughout the interview book Moebius: Entretiens avec Numa Sadoul (ISBN 2203380152). In the book his mother Pauline is also featured in her only known interview, relating events surrounding Giraud's earliest years such as the family's headlong flight from the German invaders during the tumultuous 1940 Blitzkrieg months, being bombed by Stukas along the way. (pp. 146–147). Whereas the relationship with his mother had been mended, Giraud also divulged that he had no memories of father Raymond. (pp. 26–27)

- 1 2 3 Booker, Keith M. 2010. "Giraud, Jean" in Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels, Volume 1ABC-CLIO pp. 259–60

- ↑ [Archived index at the Wayback Machine. "page-Biographie"] Check

|url=value (help). moebius.fr. 5 January 2011. - ↑ Blueberry L'integrale 1, Paris: Dargaud 2012, p. 6, ISBN 9782205071238; As in so many other countries at the time, comics were considered by the conservative establishment as a perfidious influence on their youths, and the medium still had decades to go before it attained the revered status in French culture as "le neuvième art" (the 9th art)

- ↑ Moebius Redux: Mexico

- ↑ In Search of Moebius/Moebius Redux: A Life in Pictures 2007 on YouTube

- 1 2 Giraud, Jean. "Introduction to King of the Buffalo by Jean Giraud". 1989. Moebius 9: Blueberry. Graphitti designs.

- 1 2 3 "Jean Giraud". Comiclopedia. Lambiek.

- ↑ Schtroumpf, Les cahier de la bande dessinee, issue 25, 1974, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Two educational books, Hommes et cavernes (1957, OCLC 300051389), Amérique an mille (1959, OCLC 936885225), and one novel for girls, Sept filles dans la brousse (1958, OCLC 759796722)

- ↑ Sapristi!, issue 27, Winter 1993, p. 77; Invariably overlooked by Giraud scholars, Bonux-Boy was a digest-sized marketing enticer for a French detergent of the same name, conceived by its marketing manager, Jijé's son Benoit Gillain. For Giraud however, it was nevertheless of seminal importance, as his work therein showed a marked progression over the work he had provided previously for Fleurus, indicating he had continued to work on his style during his military service.

- ↑ http://www.jmcharlier.com/blueberry1.php#1

- ↑ Close friend Mézières, like Giraud passionate about Westerns and the Far West, took it up a notch, when he too left at about the same time for the United States, actually working as a cowboy for two years, albeit not in the South-West, but rather in the North-West.

- ↑ http://bdzoom.com/47677/patrimoine/pour-se-souvenir-de-jean-giraud%E2%80%A6/

- 1 2 3 Jean-Marc Lofficier. 1989. "The Past Master", in Moebius 5: Blueberry. Graphitti designs.

- 1 2 Booker Keith M. 201. "Blueberry" in Encyclopedia of comic books and graphic novels, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 69

- ↑ Dargaud archive: "C'est en 1963 qu'est créé ce personnage pour PILOTE par Charlier et Giraud."

- ↑ Booker Keith M. 201. "Western Comics" in Encyclopedia of comic books and graphic novels, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 691

- ↑ Jean-Marc Lofficier. 1989. "Gone with the Wind Revisited", in Moebius 9: Blueberry. Graphitti designs.

- ↑ Le Blog des Humanoïdes Associés: Adieu Mœbius, merci Mœbius

- 1 2 Lofficier, Jean-Marc (December 1988). "Moebius". Comics Interview (64). Fictioneer Books. pp. 24–37.

- ↑ "Breasts and Beasts: Some Prominent Figures in the History of Fantasy Art." 2006. Dalhousie University

- ↑ Grove, Laurence. 2010. Comics in French: the European bande dessinée in context Berghahn Books p. 46

- ↑ Libiot, Eric (4 January 2007). "Giraud s'aventure dans XIII" (in French). L'Express.

- ↑ Lestavel, François (18 December 2012). "Yves Sente et Jean Van Hamme: le succès en série" (in French). Paris Match.

- ↑ Grove, Laurence. 2010. Comics in French: the European bande dessinée in context Berghahn Books p. 211

- 1 2 3 Minovitz, Ethan (11 March 2012). "French cartoonist Jean "Moebius" Giraud dies at 73". Big Cartoon News. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Collective (1986). L'univers de 1: Gir. Paris: Dargaud. p. 85. ISBN 2205029452.

- ↑ Official website on the Miyazaki-Moebius exhibition at La Monnaie, Paris

- ↑ Museum web page for exhibition, Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Hachereau, Dominique. "BD – Bande Dessinee et Philatelie" (in French). Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Expo GIR et MOEBIUS, 1997, accessed 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "Blueberry au bord du Nervous break-down...". bdparadisio

- ↑ "Jean Giraud sur un scénario de Jean-Michel Charlier". bdparadisio.com (French)

- ↑ "Moebius – Jean Giraud – Video del Maestro all' opera" on YouTube. 30 May 2008

- ↑ Svane, Erik; Surmann, Martin; Ledoux, Alain; Jurgeit, Martin; Förster, Horst; Berner, Gerhard (2003). Zack-Dossier 1: Blueberry und der europäische Western-Comic. Berlin: Mosaik. p. 12. ISBN 393266759X.

- ↑ Hamel, Ian (10 March 2012). "Décès à Paris du dessinateur et scénariste de BD Moebius". Le Point.fr.

- ↑ Connelly, Brendon (10 March 2012). "Moebius, aka Jean Girard, aka Gir, Has Passed Away". Bleeding Cool.

- ↑ "Jean Giraud alias Moebius, père de Blueberry, s'efface". Libération. 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "French ‘master of comics’ artist Moebius dies". euronews.com. 10 March 2012.

- ↑ "L’enterrement de Jean Giraud, alias Moebius, aura lieu à Paris le 15 mars". Frencesoir.fr.

- 1 2 3 4 "Comic book artist Moebius dies". Jakarta Globe. 11 March 2012

- ↑ Bordenave, Julie. "Miyazaki Moebius : coup d'envoi". AnimeLand.com. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ↑ Ghibli Museum (ed.). Ghibli Museumdiary 2002-08-01 (in Japanese). Tokuma Memorial Cultural Foundation for Animation. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ↑ "Miyazaki and Moebius". Nausicaa.net. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "R.I.P. Jean 'Moebius' Giraud (1938–2012) – ComicsAlliance | Comic book culture, news, humor, commentary, and reviews". ComicsAlliance. 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Did Blade Runner influence William Gibson when he wrote his cyberpunk classic, Neuromancer?". brmovie.com Archived 9 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Italian television interview cited in Mollica, Vincenzo (2002), Fellini mon ami, Paris: Anatolia, 84.

- ↑ "11° Salone Internationale del Comics, del Film di Animazione e dell'Illustrazione" (in Italian). immaginecentrostudi.org.

- ↑ "14° Salone Internationale del Comics, del Film di Animazione e dell'Illustrazione" (in Italian). immaginecentrostudi.org.

- ↑ noosfere.org. "Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire" (in French).

- 1 2 3 "Giraud, Jean ('Moebius')". The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Art Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ "Science Fiction Hall of Fame" at the Wayback Machine (archived 21 July 2011). [Quote: "EMP is proud to announce the 2011 Hall of Fame inductees: ..."]. May/June/July 2011. EMP Museum (empmuseum.org). Archived 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ↑ Randy Lofficier and Jean-Marc Lofficier, Moebius Comics No. 1, Caliber Comics, 1996.

Sources

- Jean Giraud (Gir, Moebius) publications in Spirou, Pilote, Métal Hurlant, Fluide Glacial, (A SUIVRE) and BoDoï BDoubliées (French)

- Jean Giraud albums Bedetheque (French)

- Moebius albums Bedetheque (French)

- Jean Giraud on Bdparadisio.com (French)

- Jean Giraud Moebius on Artfacts.net, about the expositions of original drawings of Moebius.

- Moebius publications in English www.europeancomics.net

- Illustration Art Gallery

- Jean Giraud at the Comic Book DB

Further reading

- Erik Svane, Martin Surmann, Alain Ledoux, Martin Jurgeit, Gerhard Förster, Horst Berner (2003, Zack-Dossier 1; Berlin: Mosaik): "Blueberry und der europäische Western-Comic" (German) ISBN 3-932667-59-X

External links

- Official website (French)

- Twists of Fate on France magazine

- Jean Giraud profile on Artfacts

- Giraud on bpip.com

- Jean Giraud on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Moebius at the Internet Movie Database

- Giraud at the Internet Movie Database

- Moebius at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Moebius on contours-art.de (German)

- Interview Jean Giraud – The Eternal Traveler

- "Jean Moebius Giraud biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- French comic book illustrator Moebius dies in Paris by Radio France Internationale English service

- Moebius Interview - Virtual Reality – ArtFutura

- Moebius, 1938–2012 at Library of Congress Authorities – with 31 catalogue records