Judaism in Australia

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

97,335[1] 0.5% of Australia's population | |

| Languages | |

| Australian English, Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, Hungarian, Romanian, Arabic |

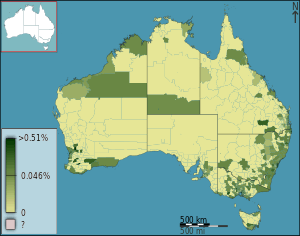

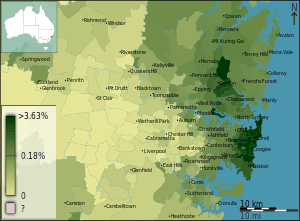

Judaism is a minority religion in Australia. 97,335 Australians identified as Jewish in the 2011 census, which accounts for about 0.5% of the population.[2]

History

In 1830 the first Jewish wedding in Australia was celebrated, the contracting parties being Moses Joseph and Rosetta Nathan.[3]

Jewish immigration came at a time of antisemitism and the Returned Services League and other groups publicized cartoons to encourage the government and the immigration Minister Arthur A. Calwell to stem the flow of Jewish immigrants.[4]

Affiliations

Until the 1930s, all synagogues in Australia were affiliated with Orthodox, acknowledging leadership of the Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom. To this day, about 70% of synagogues in Australia are Orthodox.

There had been at least two short-lived efforts to establish Reform congregations, the first as early as the 1890s. However, in 1930, under the leadership of Ada Phillips, a Liberal or Progressive congregation, Temple Beth Israel (Melbourne, Australia), was permanently established in Melbourne. In 1938 the long-serving Senior Rabbi, Rabbi Dr Herman Sanger, was instrumental in establishing another synagogue, Temple Emanuel in Sydney. He also played a part in founding a number of other Liberal synagogues in other cities in both Australia and New Zealand. The first Australian-born rabbi, Rabbi Dr John Levi, served the Australian Liberal movement.[5]

Demographics

About 90 percent of the Australian Jewish community live in Sydney and Melbourne.[6] Melbourne Ports has the largest Jewish community of any electorate in Australia.[7]

The Jewish Community Council of Victoria has estimated that 60,000 Australian Jews live in Victoria.[8] In Frankston, the Jewish community has nearly doubled since 2007.[9]

In Adelaide Australian Jews have been present throughout the history of the city, with many successful civic leaders and people in the arts.[10]

The same social and cultural characteristics of Australia that facilitated the extraordinary economic, political, and social success of the Australian Jewish community have also been attributed to contributing to widespread assimilation.[11]

People

- Raymond Apple, Senior Rabbi of the Great Synagogue of Sydney

- Zelman Cowen, Politician, Governor-General of Australia

- Alan Finkel, Australia's Chief Scientist

- John Gandel, Businessman, philanthropist

- David Gonski, Businessman, philanthropist

- David Helfgott, Pianist (inspired Academy Award-winning film Shine)

- Isaac Isaacs, Judge and politician, Chief Justice of Australia, and Governor-General of Australia

- Barrie Kosky, Opera director

- Solomon Lew, Businessman

- Frank Lowy, Slovak-born Israeli Australian businessman

- Miriam Margolyes, British-Australian actress

- John Monash, Australian General

- Bernhard Neumann, German-born British-Australian mathematician

- Anthony Pratt, Australian businessman

- Peter Singer, Philosopher

- Troye Sivan, South African-born Australian singer, actor and YouTuber

- Victor Smorgon, Businessman

- Harry Triguboff, Chinese-born Australian businessman

- Alex Waislitz, Businessman

- Ghil'ad Zuckermann, Linguist and revivalist

See also

References

- ↑ "Australia's Jewish population rises to 100,000". Haaretz. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- ↑ "Australia's Jewish population rises to 100,000 | The Israeli News". Haaretz. 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Suzanne D. Rutland (2008). "Jews". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ Rutland, Susan, 2005, The Jews in Australia

- ↑ Rubinstein and Freeman, (Editors), "A Time to Keep: The story of Temple Beth Israel: 1930 to 2005" A Special publication of the Australian Jewish Historical Society, 2005.

- ↑ Goldberg, Dan (2013-01-02). "Australian Jews may top Forbes' rich list, but 20% live on poverty line Israel News". Haaretz. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ http://blogs.crikey.com.au/pollbludger/2012/12/22/seat-of-the-week-melbourne-ports/

- ↑ "Jewish Community Council of Victoria (JCCV) - Overview". JCCV. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ "Census shows Jews are on the move | The Australian Jewish News". Jewishnews.net.au. 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Adelaide Jewish Museum Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Postrel, Virginia (May 1993). "Uncommon Culture". Reason Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-05.