Le Mans (film)

| Le Mans | |

|---|---|

|

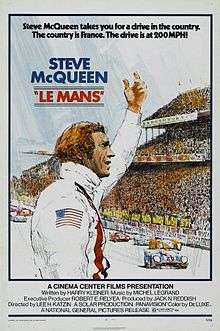

Theatrical release poster by Tom Jung | |

| Directed by | Lee H. Katzin |

| Produced by | Jack N. Reddish [1] |

| Written by | Harry Kleiner |

| Starring | Steve McQueen |

| Music by | Michel Legrand |

| Cinematography |

René Guissart Jr. Robert B. Hauser |

| Edited by |

Ghislaine Desjonquères Donald W. Ernst John Woodcock |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | National General Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7.6 million (est.) |

| Box office | $5.5 million (North American rentals)[2] |

Le Mans is a 1971 film depicting a fictional 24 Hours of Le Mans auto race starring Steve McQueen and directed by Lee H. Katzin. It features actual footage captured during the 1970 race held the previous June.[3]

Released in June 1971 and given a G rating,[1] the film was a flop at the box office in the United States. However, unlike the similar but much more successful 1966 film Grand Prix (for which McQueen had turned down the starring role, given afterwards to James Garner), LeMans remains popular today as an historically accurate depiction of its era, albeit focusing on racing at the expense of both plot and dialogue.

Plot

Top flight LeMans racing driver Michael Delaney spots former rival Piero Belgetti's widow Lisa buying flowers in the days before the fictional 1971 race; he then drives to the scene of the accident which killed her husband the previous year. He has a flashback of Belgetti losing control of his Ferrari, forcing him to crash as well.

Like many others, Lisa appears to feel Delaney was responsible, at least in part, for the accident. At the race she is understandably downcast while working through her emotions. In an awkward scene, Delaney looks for a place to sit in the crowded track commissary, only to ask Lisa if he may join her. There is obvious tension between them, but also respect and a hint of mutual attraction.

After 13 hours of racing, Erich Stahler spins his Ferrari 512 at Indianapolis Corner, causing teammate Claude Aurac to veer off the track in a major accident. Dodging the flames of Aurac's car, Delaney avoids a slower car but collides with the crash barrier and goes off the track, totaling his Porsche 917. Both survive, but Aurac's injuries are extensive and he is medevaced to a hospital by helicopter. Lisa appears at the track clinic where Delaney is briefly treated. She is distraught at his near miss, which stirs up emotions from Piero's passing she had been seeking to put in the past. Delaney consoles her and rescues her from a horde of reporters. After he puts her in a waiting car, a journalist asks Delaney whether his and Aurac's accident can be compared to the one with Belgetti in the previous year's race. Delaney merely stares him down.

Porsche driver Johann Ritter senses that his wife, Anna, would like for him to quit racing. He suggests it, thinking she will be overjoyed. She demurs and says she would like it only if he likes it. He chides her a bit about not being entirely honest. Later the decision is taken out of his hands when team manager David Townsend replaces him for not being quick enough on the track. Anna tries to comfort him, reminding him that he was planning to quit anyway.

Lisa goes to Delaney's trailer to talk with him. After his brush with death she is even more drawn to him and despairs that he may meet the same fate as her husband, but Delaney finds the thrill too addictive to quit. Townsend enters and asks him to take over driving Ritter's car, not to win the race but serve as a spoiler to ensure a victory for team Porsche. After a moment's unspoken communion with Lisa, he follows Townsend.

In the closing minutes of the race the two Porsches and their rival Ferraris vie for the win, with Delaney in the #21 car and teammate Larry Wilson in #22. The Ferrari leading the race retires due to a flat tire, leaving Wilson in the lead and only Delaney's archrival, Stahler, to contend. The faster pair quickly catch Wilson. Delaney passes Stahler for second place.

Slower traffic in his lane forces Delaney to brake, allowing Stahler to overtake on the left. Delaney drafts the German, then both move alongside Wilson. Rather than try to pass Stahler, then possibly Wilson, Delaney drops back and bumps Stahler, forcing him to throttle back to avoid spinning out when the Ferrari goes partially off the pavement. Delaney then uses the guardrail to block the aggressive Stahler's last ditch effort to overhaul, ensuring a win for Porsche. The teammates cross the finish line 1-2.

Cast

- Steve McQueen as Michael Delaney

- Siegfried Rauch as Erich Stahler

- Elga Andersen as Lisa Belgetti

- Ronald Leigh-Hunt as David Townsend

- Fred Haltiner as Johann Ritter

- Luc Merenda as Claude Aurac

- Christopher Waite as Larry Wilson

- Louise Edlind as Mrs. Anna Ritter

- Angelo Infanti as Lugo Abratte

- Jean-Claude Bercq as Paul-Jacques Dion

- Michele Scalera as Vito Scaliso

- Gino Cassani as Loretto Fuselli

- Alfred Bell as Tommy Hopkins

- Carlo Cecchi as Paolo Scadenza

Production

Le Mans was filmed on location on the Le Mans circuit between June and November 1970, including during that season's actual 24 Hours of Le Mans race in mid-June. [3] McQueen had intended to race a Porsche 917 together with Jackie Stewart,[4][5] but the #26 entry was not accepted. Instead, he is depicted as starting the race in the blue #20 Gulf-Porsche 917K driven by Jo Siffert and Brian Redman. The race-leading white #25 Porsche 917 "Long tail" was piloted by Vic Elford and Kurt Ahrens, Jr..

The Porsche 908/2 which McQueen had previously co-driven to a second place in the 12 Hours of Sebring was entered in the race by Solar Productions, complete with heavy movie cameras capturing actual racing footage. This #29 camera car, which can be briefly seen in the starting grid covered with a black sheet (at approximately 17:51) and again at just before the 79 minute-mark (at 1:18:42) racing past the starting line, was driven by Porsche's Herbert Linge and Jonathan Williams.[6] It travelled 282 laps, or 3,798 kilometres (2,360 miles) and finished the race in 9th position,[7] but it was not classified as it had not covered the required minimum distance due to the stops to change film reels. It did, however, manage to finish 2nd in the P3.0 class.

Additional footage shot after the race used actual Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512s, in competition liveries.[6] In the crash scenes comparatively expendable technologically obsolete Lola T70 chassis were fitted with replica Porsche and Ferrari bodywork.

Though depicted as the factory-backed Scuderia Ferrari team, the 512's used were borrowed from Belgian Ferrari distributor Jacques Swaters after Enzo Ferrari balked at supplying cars due to the script's Porsche team victory.

McQueen had wanted to employ Christopher Chapman's new multi-dynamic image technique in the film, as had been done at his instigation with The Thomas Crown Affair, in which he starred in 1968. Chapman advised against it, much to McQueen's disappointment; in Chapman's words, “it was much too big a film, with too many writers; it wouldn't work that way.”[8]

Legacy

Despite the film's original lack of success, it now has a large cult following, who appreciate its authenticity. A time capsule for how Le Mans was run in its day – the men, machines, rules, and racing ethos – it is celebrated for using the actual Le Mans circuit, footage of the real race captured by a participating car, and renowned drivers and actual Le Mans race cars in the recreations staged to flesh out the movie's plot. The expense of doing so and the risks involved are prohibitive today, replaced by simulated green screen fabrications and CGI imagery.

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans is a 2015 documentary film, detailing the actor's quest to make the 1971 film Le Mans.

See also

- List of American films of 1971

- List of American films of 1970

- TAG Heuer Monaco

- Grand Prix (film)

- Truth in 24

References

- 1 2 "Le Mans". Milwaukee Journal. (advertisement). June 22, 1971. p. 13.

- ↑ "All-time Film Rental Champs", Variety, 7 January 1976 p 46

- 1 2 Huber, Jim (July 4, 1971). "'Le Mans' gives a gripping insight into racing world". Spartanburg (SC) Herald-Journal. p. D6.

- ↑ "McQueen may join Stewart". St. Petersburg Independent. Associated Press. March 2, 1970. p. 5C.

- ↑ Bell, Derek (April 22, 1988). "McQueen: The main man of LeMans". Palm Beach Post. p. 9C.

- 1 2 Williams, Jonathan (June 27, 2011). "Le Mans 1970". AutoWeek. Crain Communications Inc. 61 (13): 24–28. ISSN 0192-9674.

- ↑ http://www.formula2.net/1970.htm

- ↑ The Personal Vision of Christopher Chapman, CM, RCA, CSC, CFE, Ontario Film Institute; 1989 interview published March, 2010, http://www.csc.ca/news/default.asp?aID=1423

Further reading

- Michael Keyser, Jonathan Williams, A French Kiss With Death, Bentley Publishers, 1999 - A lengthy, profusely illustrated and very readable history of the making of the movie

External links

- Le Mans at the Internet Movie Database

- Le Mans at the TCM Movie Database

- Le Mans at AllMovie

- Sebring Results