Levamisole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ergamisol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a697011 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | P02CE01 (WHO) QP52AE01 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Biological half-life | 3–4 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (70%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

14769-73-4 |

| PubChem (CID) | 26879 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7210 |

| DrugBank |

DB00848 |

| ChemSpider |

25037 |

| UNII |

2880D3468G |

| KEGG |

D08114 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:6432 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1454 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.035.290 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

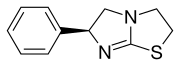

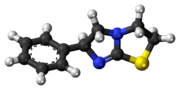

| Formula | C11H12N2S |

| Molar mass | 204.292 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Density | 1.31 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 60 °C (140 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Levamisole, marketed under the trade name Ergamisol, is a medication used to treat parasitic worm infections.[1] It has also been studied as a method to stimulate the immune system as part of the treatment of cancer.[2] Levamisole remains in veterinary use as a dewormer for livestock.

The most serious side effect of levamisole is low white blood cells that leaves person vulnerable to infection. It belongs to the class of synthetic imidazothiazole derivatives.

Levamisole was discovered in 1966 by Janssen Pharmaceutica.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[4] It was withdrawn from the U.S. and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to the risk of side effects and the availability of more effective medications.[5] The medication has been used as an adulterant in cocaine sold in the United States, Canada and United Kingdom, resulting in serious side effects.[6][7][8]

Medical uses

Levamisole was originally used as an anthelmintic to treat worm infestations in both humans and animals. Levamisole works as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist that causes continued stimulation of the parasitic worm muscles, leading to paralysis. In countries that still permit the use of levamisole, the recommended dose for anthelmintic therapy is a single dose, with a repeated dose 7 days later if needed for a severe hookworm infection.[9] Most current commercial preparations are intended for veterinary use as a dewormer in cattle, pigs, and sheep. However, levamisole has also recently gained prominence among aquarists as an effective treatment for Camallanus roundworm infestations in freshwater tropical fish.[10]

After being pulled from the market in the U.S. and Canada in 1999 and 2003, respectively, levamisole has been tested in combination with fluorouracil to treat colon cancer. Evidence from clinical trials support its addition to fluorouracil therapy to benefit patients with colon cancer. In some of the leukemic cell line studies, both levamisole and tetramisole showed similar effect.[11]

Levamisole has been used to treat a variety of dermatologic conditions, including skin infections, leprosy, warts, lichen planus, and aphthous ulcers.[12]

An interesting adverse side effect these reviewers reported in passing was "neurologic excitement". Later papers, from the Janssen group and others, indicate levamisole and its enantiomer, dexamisole, have some mood-elevating or antidepressant properties, although this was never a marketed use of the drug.[13][14]

Adverse effects

One of the more serious side effects of levamisole is agranulocytosis, or the depletion of the white blood cells. In particular, neutrophils appear to be affected the most. This occurs in 0.08–5% of the studied populations.[15] There have also been reports of levamisole induced necrosis syndrome in which erythematous painful papules can appear almost anywhere on skin.

Metabolism

Levamisole is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and metabolized in the liver. Its time to peak plasma concentration is 1.5–2 hours. The plasma elimination half-life is fairly quick at 3–4 hours which can contribute to not detecting Levamisole intoxication. The metabolite half-life is 16 hours. Levamisole's excretion is primarily through the kidneys, with about 70% being excreted over 3 days. Only about 5% is excreted as unchanged levamisole.[16][17]

Drug testing of racehorse urine has led to the revelation that among levamisole equine metabolites are both pemoline and aminorex, stimulants that are forbidden by racing authorities.[18][19][20] Further testing confirmed aminorex in human and canine urine, meaning that both humans and dogs also metabolize levamisole into aminorex.[21] The stimulant properties of aminorex contribute to the use of levamisole as a cocaine adulterant, potentiating the reinforcing effects of cocaine.

Detection in body fluids

Levamisole may be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine as a diagnostic tool in clinical poisoning situations or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of suspicious deaths involving adulterated street drugs. About 3% of an oral dose is eliminated unchanged in the 24-hour urine of humans. A post mortem blood levamisole concentration of 2.2 mg/L was present in a woman who died of a cocaine overdose.[22][23]

Illicit use

Levamisole has increasingly been used as a cutting agent in cocaine sold around the globe with the highest incidence being in the USA. In 2008–2009, levamisole was found in 69% of cocaine samples seized by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).[6] By April 2011, the DEA reported the adulterant was found in 82% of seizures.[24]

Levamisole adds bulk and weight to powdered cocaine (whereas other adulterants produce smaller "rocks" of cocaine) and makes the drug appear purer.[25] In a series of investigative articles for The Stranger, Brendan Kiley details other rationales for levamisole's rise as an adulterant: possible stimulant effects, a similar appearance to cocaine, and an ability to pass street purity tests.[26]

Levamisole suppresses the production of white blood cells, resulting in neutropenia and agranulocytosis. With the increasing use of levamisole as an adulterant, a number of these complications have been reported among cocaine users.[6][27][28] Levamisole has also been linked to a risk of vasculitis,[29] and two cases of vasculitic skin necrosis have been reported in users of cocaine adulterated with levamisole.[30]

Levamisole-tainted cocaine was linked to several high-profile deaths. Toxicology reports showed levamisole, along with cocaine, was present in DJ AM's body at the time of his death.[31] Andrew Koppel, son of newsman Ted Koppel, was also found with levamisole in his body after his death was ruled a drug overdose.[32] More recently it has also been suspected in the death of a Sydney teenager.[33]

In response to the dangers, The Stranger, People's Harm-Reduction Alliance and DanceSafe began producing tests to identify levamisole's presence in cocaine. The kits include a survey postcard, and one revealed its presence in a 1/4-kg block of cocaine, indicating both users and dealers were using the kits.[34]

Chemistry

The original synthesis at Janssen Pharmaceutica resulted in the preparation of a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, whose hydrochloride salt was reported to have a melting point of 264–265 °C; the free base of the racemate has a melting point of 87–89 °C.

Toxicity

The LD50 (intravenous, mouse) is 22 mg/kg.[35]

Laboratory use

Levamisole reversibly and noncompetitively inhibits most isoforms of alkaline phosphatase (e.g., human liver, bone, kidney, and spleen) except the intestinal and placental isoform.[36] It is thus used as an inhibitor along with substrate to reduce background alkaline phosphatase activity in biomedical assays involving detection signal amplification by intestinal alkaline phosphatase, for example in in situ hybridization or Western blot protocols.

It is used to immobilize the nematode C. elegans on glass slides for imaging and dissection.[37]

In a C. elegans behavioral assay, analyzing the time course of paralysis provides information about the neuromuscular junction. Levamisole acts as an acetylcholine receptor agonist, which leads to muscle contraction. Continuing activation leads to paralysis. The time course of paralysis provides information about the acetylcholine receptors on the muscle. For example, mutants with fewer acetylcholine receptors may paralyze slower than wild type.[38]

References

- ↑ Keiser, J; Utzinger, J (23 April 2008). "Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis.". JAMA. 299 (16): 1937–48. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937. PMID 18430913.

- ↑ Dillman, RO (February 2011). "Cancer immunotherapy.". Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals. 26 (1): 1–64. doi:10.1089/cbr.2010.0902. PMID 21355777.

- ↑ Prevenier, Martha Howelland Walter (2001). From reliable sources : an introduction to historical methods (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca: Cornell university press. p. 77. ISBN 9780801485602.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Products Discontinued from the Market Since Publication of the 2000 CPS". Canadian Pharmacists Association. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- 1 2 3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 2009). "Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use - four States, March 2008-November 2009". Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58 (49): 1381–5. PMID 20019655.

- ↑ Chang, A; Osterloh, J; Thomas, J (September 2010). "Levamisole: a dangerous new cocaine adulterant.". Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 88 (3): 408–11. doi:10.1038/clpt.2010.156. PMID 20668440.

- ↑ https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411574/acmd_final_report_12_03_2015.pdf

- ↑ "Levamisole (Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference)". Lexicomp. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Sanford, Shari (2007). "Levamisole Hydrochloride: Its application and usage in freshwater aquariums". Loaches Online. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ (Chirigos et al. (1969, 1973, 1975)).

- ↑ Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM (2004). "Levamisole in dermatology: a review". Am J Clin Dermatol. 5 (2): 97–104. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405020-00004. PMID 15109274.

- ↑ Vanhoutte, P. M.; et al. (1977). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 200: 127–140. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Przegalinski, E.; et al. (1980). Pol. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 32: 21–29. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Levamisole" (PDF). DEA. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Kouassi, E (1986). "Novel assay and pharmacokinetics of levamisole and p-hydroxylevamisole in human plasma and urine". Biopharmaceutics and Drug Disposition. 7 (1): 71–89. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510070110. PMID 3754161.

- ↑ Luyckx, M (1982). "Pharmacokinetics of levamisole in healthy subjects and cancer patients". European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 7 (4): 247–54. doi:10.1007/bf03189626. PMID 7166176.

- ↑ J. Guiterrez et al. (2010) "Pemoline and tetramisole 'positives' in English racehorses following levamisole administration." Irish Veterinary Journal 63:8 498-500.

- ↑ E.N. Ho et al. (2009) "Aminorex and pemoline as metabolites of levamisole in the horse." Anal Chem Acta. 638(1); 58-68.

- ↑ J. Scarth et al. (2010) "The use of in vitro drug metabolism studies to complement, reduce and refine in vivo administrations in medication and doping control." Proceedings of the 18th International Conference of Racing Analyists and Veterinarians. pp 213-222

- ↑ Bertol E, Mari F, Milia MG, Politi L, Furlanetto S, Karch SB (2011). "[Determination of aminorex in human urine samples by GC-MS after use of levamisole.]". J Pharm Biomed Anal. 15 (55): 1186–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2011.03.039. PMID 21531521.

- ↑ Vandamme, TF; Demoustier, M; Rollmann, B (1995). "Quantitation of levamisole in plasma using high performance liquid chromatography". Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 20 (2): 145–149. doi:10.1007/bf03226369.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2011, pp.901-902. http://www.biomedicalpublications.com/levamisole.pdf.

- ↑ Moisse, Katie (2011-06-23). "Cocaine Laced With Veterinary Drug Levamisole Eats Away at Flesh". ABC News. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ↑ Doheny, Kathleen (Jun 1, 2010). "Contaminated Cocaine Can Cause Flesh to Rot". Yahoo!. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ↑ Kiley, Brendan (August 17, 2010). "The Mystery of the Tainted Cocaine". The Stranger. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Nancy Y Zhu; Donald F. LeGatt; A Robert Turner (February 2009). "Agranulocytosis After Consumption of Cocaine Adulterated With Levamisole". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (4): 287–289. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00102 (inactive 2016-10-25). PMID 19153405. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ↑ Kinzie, Erik (April 2009). "Levamisole Found in Patients Using Cocaine". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 53 (4): 546–7. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.10.017. PMID 19303517. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Menni S, Pistritto G, Gianotti R, Ghio L, Edefonti A (1997). "Ear lobe bilateral necrosis by levamisole-induced occlusive vasculitis in a pediatric patient". Pediatr Dermatol. 14 (6): 477–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00695.x. PMID 9436850.

- ↑ Bradford, M., Rosenberg, B., Moreno, J., Dumyati, G. (June 2010). "Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole". Ann. Intern. Med. 152 (11): 758–9. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00026 (inactive 2016-10-25). PMID 20513844.

- ↑ "'Kate Plus Eight' is enough". The San Francisco Chronicle. September 29, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ↑ Parascandola, Rocco (2010-06-18). "Ted Koppel's son, Andrew Koppel, overdosed on cocktail containing booze, heroin, cocaine and Valium". Daily News. New York.

- ↑ Olding, Rachel (2014-01-12). "Young man's death highlights the tragic reality of online illegal drug stores". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney.

- ↑ Brendan Kiley (September 11, 2012). "Now Drug Dealers (Not Just Users) Are Testing Their Cocaine for Levamisole". The Stranger. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ↑ J. Symoens et al. (1979). In Pharmacological and Biochemical Properties of Drug Substances, Vol. 2, (M. E. Goldberg, Ed.), pp. 407-464, Washington: American Pharmaceutical Association.

- ↑ Van Belle, H. (1976). "Alkaline phosphatase. I. Kinetics and inhibition by levamisole of purified isoenzymes from humans". Clin. Chem. 22 (7): 972–6. PMID 6169.

- ↑ http://genetics.wustl.edu/tslab/protocols/dissection-staining-in-situ/gonad-dissections/ Schedl Lab Protocol for gonad dissections

- ↑ http://www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_acetylcholine/acetylcholine.html