Sacred language

A sacred language, "holy language" (in religious context) or liturgical language is a language that is cultivated for religious reasons by people who speak another language in their daily life.

Concept

Once a language becomes associated with religious worship, its believers may ascribe virtues to the language of worship that they would not give to their native tongues. In the case of sacred texts, there is a fear of losing authenticity and accuracy by a translation or re-translation, and difficulties in achieving acceptance for a new version of a text. A sacred language is typically vested with a solemnity and dignity that the vernacular lacks. Consequently, the training of clergy in the use of a sacred language becomes an important cultural investment, and their use of the tongue is perceived to give them access to a body of knowledge that untrained lay people cannot (or should not) access. In medieval Europe, the (real or putative) ability to read (see also benefit of clergy) scripture—which was in Latin—was considered a prerogative of the priesthood, and a benchmark of literacy; until near the end of the period almost all who could read and write could do so in Latin.

Because sacred languages are ascribed with virtues that the vernacular is not perceived to have, the sacred languages typically preserve characteristics that would have been lost in the course of language development. In some cases, the sacred language is a dead language. In other cases, it may simply reflect archaic forms of a living language. For instance, 17th-century elements of the English language remain current in Protestant Christian worship through the use of the King James Bible or older versions of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. In more extreme cases, the language has changed so much from the language of the sacred texts that the liturgy is no longer comprehensible without special training.

In some instances, the sacred language may not even be (or have been) native to a local population, that is, missionaries or pilgrims may carry the sacred language to peoples who never spoke it, and to whom it is an altogether alien language.

The concept of sacred languages is distinct from that of divine languages, which are languages ascribed to the divine (i.e. God or gods) and may not necessarily be natural languages. The concept, as expressed by the name of a script, for example in Devanāgarī, the name of a script that means "of city of deities (/Gods)".

Buddhism

Theravada Buddhism uses Pali as its main liturgical language, and prefers its scriptures to be studied in the original Pali. In Thailand, Pali is written using the Thai alphabet, resulting in a Thai pronunciation of the Pali language.

Mahayana Buddhism makes little use of its original language, Sanskrit. In some Japanese rituals, Chinese texts are read out or recited with the Japanese pronunciations of their constituent characters, resulting in something unintelligible in both languages.[1] In Tibetan Buddhism, Tibetan language is used, but mantras are in Sanskrit.

Christianity

.jpg)

Christian rites, rituals, and ceremonies are not celebrated in one single sacred language. The Churches which trace their origin to the Apostles continued to use the standard languages of the first few centuries AD.

These include:

- Ecclesiastical Latin in the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic Church (N.B. While Latin is the official language of all formal works of the church, it has largely been replaced by the vernacular in liturgical use since 1964.)

- Koine Greek in the Greek Orthodox Church and Greek Catholic Church

- Church Slavonic in several of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches and sui iuris Eastern Catholic Churches

- Old Georgian in the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Georgian Catholic Church

- Classical Armenian in the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Armenian Catholic Church

- Ge'ez in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Ethiopian Catholic Church and Eritrean Orthodox Church

- Coptic in the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and Coptic Catholic Church

- Syriac in Syriac Christianity represented by the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syrian Catholic Church, Syrian Orthodox Church, Maronite Church and Saint Thomas Christian Churches

The extensive use of Greek in the Roman Liturgy has continued, in theory; it was used extensively on a regular basis during the Papal Mass, which has not been celebrated for some time. The continuous use of Greek in the Roman Liturgy came to be replaced in part by Latin by the reign of Pope Saint Damasus I. Gradually, the Roman Liturgy took on more and more Latin until, generally, only a few words of Hebrew and Greek remained. The adoption of Latin was further fostered when the Vetus Latina version of the Bible was edited and parts retranslated from the original Hebrew and Greek by Saint Jerome in his Vulgate. Latin continued as the Western Church's language of liturgy and communication. One simply practical reason for this may be that there were no standardized vernaculars throughout the Middle Ages. Church Slavonic was used for the celebration of the Roman Liturgy in the 9th century (twice, 867-873 and 880-885).

In the mid-16th century the Council of Trent rejected a proposal to introduce national languages as this was seen, among other reasons, as potentially divisive to Catholic unity.

From the end of 16th century, in coastal Croatia, the vernacular was gradually replacing Church Slavonic as liturgical language. It was being introduced in the rite of the Roman Liturgy, after the Church Slavonic language of glagolitic liturgical books, published in Rome was becoming increasingly unintelligible due to linguistical reforms, namely, adapting Church Slavonic of Croatian recension by the norms os Church Slavonic of Russian recension. For example, vernacular was used in the inquiry of bride and bridegroom as to whether they accepted their marriage-vows itself.

Jesuit missionaries to China had sought, and for a short time, received permission to translate the Roman Missal into scholarly Classical Chinese. (See Chinese Rites controversy). However, ultimately permission was revoked. Among the Algonquin and Iroquois, they received permission to translate the propers of the Mass into the vernacular.[2]

In the 20th century, Pope Pius XII granted permission for a few vernaculars to be used in a few rites, rituals, and ceremonies. This did not include the Roman Liturgy of the Mass.

The Catholic Church, long before the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican ('Vatican II') accepted and promoted the use of the non-vernacular liturgical languages listed above; vernacular (i.e. modern or native) languages were never used liturgically until 1964, when the first permissions were given for certain parts of the Roman Liturgy to be celebrated in certain approved vernacular translations. The use of vernacular language in liturgical practice created controversy for a minority of Catholics, and opposition to liturgical vernacular is a major tenet of the Catholic Traditionalist movement.

In the 20th century, Vatican II set out to protect the use of Latin as a liturgical language. To a large degree, its prescription was initially disregarded and the vernacular became not only standard, but generally used exclusively in the liturgy. Latin, which remains the chief language of the Roman Rite, is the main language of the Roman Missal (the official book of liturgy for the Latin Rite) and of the Code of Canon Law, and use of liturgical Latin is still encouraged. Large-scale papal ceremonies often make use of it. Meanwhile, the numerous Eastern Catholic Churches in union with Rome each have their own respective 'parent-language'. As a subsidiary issue, unrelated to liturgy, the Eastern Code of Canon Law, for the sake of convenience, has been promulgated in Latin.

Eastern Orthodox Churches vary in their use of liturgical languages within Church services. Koine Greek and Church Slavonic are the main sacred languages used in the Churches of the Eastern Orthodox communion. However, the Eastern Orthodox Church permits other languages to be used for liturgical worship, and each country often has the liturgical services in their own language. This has led to a wide variety of languages used for liturgical worship, but there is still uniformity in the liturgical worship itself. So one can attend an Orthodox service in another location and the service will be (relatively) the same.

Liturgical languages used in the Eastern Orthodox Church include: Koine Greek, Church Slavonic, Romanian, Georgian, Arabic, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Serbian, English, Spanish, French, Polish, Portuguese, Albanian, Finnish, Swedish, Chinese, Estonian, Korean, Japanese, several African languages, and other world languages.

Oriental Orthodox Churches regularly pray in the vernacular of the community within which a Church outside of its ancestral land is located. However some clergymen and communities prefer to retain their traditional language or use a combination of languages.

Many Anabaptist groups, such as the Amish, use High German in their worship despite not speaking it amongst themselves.

Hinduism

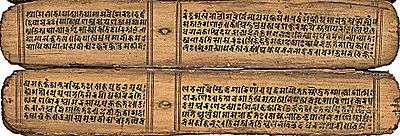

Hinduism is traditionally considered to have two liturgical languages, Sanskrit and Tamil. Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, Bhagavadgita, Puranas like Bhagavatam, and the Upanishads, and various other liturgical texts such as the Sahasranama, Chamakam and Rudram. It is also the tongue of most Hindu rituals.

Tamil is the language of the 12 Tirumurais (which consists of the great devotional hymns of Tevaram, Tiruvacakam etc.,) and the Nalayira Divya Prabandham (considered to be the essence of the Vedas, in Tamil, and all in praise of Lord Vishnu). These devotional hymns, which were sung in almost every Shiva and Vishnu temple of the South India, the then Tamil country and even North Indian temples like Badrinath Temple, are considered to be the basis for the Bhakti movement.[3]

The people following Kaumaram, Vainavam, Shaivam sects of South India and use Tamil as liturgical language along with Sanskrit. Divya Prabandha is chanted in most of the South Indian Vishnu temples like Tirupati.Indian literature . Dravidian people considered their language Tamil to be sacred and divine with equal status to Sanskrit within temple rituals, which is still being followed even by some temples in present-day non-Tamil speaking areas. The Divya Prabhandams and Devarams are referred to as Dravida Vedam (Tamil Veda).

A long-standing myth states that Sanskrit and Tamil emerged from either side of Lord Shiva's divine drum of creation as he danced the dance of creation as Nataraja or sound of cosmic force.

- Also most of the devotional texts on Lord Murugan or Subrahmanyan are in Tamil and references in the Ancient Tamil literature traces the origin of Lord Murugan to the Ancient Tamil country.[4]

- Tamils consider their language itself a goddess Tamil Tai. She is worshiped by Tamils all over the world. In Madurai, there is a temple for Goddess Tamil Tai.

Islam

Classical Arabic is the sacred language of Islam. It is the language of the Qur'an, and the native language of Muhammad. Like Latin in medieval Europe, Arabic is both the spoken and the liturgical language in the Arab World. Some minor Muslim affiliates, particularly the Nizaris of Khorasan and Badakhshan, witnessed and experienced Persian as a liturgical language during the Alamut period (1094 to 1256 CE) and post-Alamut period (1256 to present).

The spread of Islam throughout Maritime Southeast Asia witnessed and experienced Malay as a liturgical language.

Judaism

The core of the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) is written in Biblical Hebrew, referred to by some Jews as Leshon Ha-Kodesh (לשון הקודש), "The Holy Language". Hebrew (and, in the case of a few texts such as the Kaddish, Aramaic) remains the traditional language of Jewish religious services, although its usage today varies by denomination: Orthodox services are almost entirely in Hebrew, Reform services make more use of the national language and only use Hebrew for a few prayers and hymns, and Conservative services usually fall somewhere in-between. Rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic are used extensively by the Orthodox for writing religious texts. Among many segments of the Ultra-Orthodox, Yiddish, although not used in liturgy, is used for religious purposes, such as for Torah study.

Among the Sephardim Ladino, a calque of Hebrew or Aramaic syntax and Castilian words, was used for sacred translations such as the Ferrara Bible. It was also used during the Sephardi liturgy. Note that the name Ladino is also used for Judeo-Spanish, a dialect of Castilian used by Sephardim as an everyday language until the 20th century.[5][6]

Donmeh

The Donmeh, the descendants of Sephardic followers of Sabbatai Tsevi who converted to Islam, used Judeo-Spanish in some of their prayers, but this seems limited nowadays to the older generations.

Lingayatism

Kannada is the language of Lingayatism. Most of the literature of this Shaivite tradition is in Kannada, but some literature is also found in Telugu and Sanskrit.

Listing of sacred languages

- Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur'an; it differs from the various forms of contemporary spoken Arabic in lexical and grammatical areas.

- Aramaic, the mother tongue of Jesus and his disciples. Used by the earliest Christians, the Nazarenes. Jesus' native western accent survives today in the form of Western Neo-Aramaic in a few remote villages. Aramaic, alongside Hebrew was the language of Post Babylonian Judaism, employed in the Talmud. It also appears in the later books of the Hebrew Bible. It is still used in liturgy today by conservative sects of Judaism, noticeably the Temani.

- Avestan, the language of the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism.

- Classical Chinese, the language of older Chinese literature and the Confucian, Taoist, and in East Asia also of the Mahayana Buddhist sacred texts, which also differs markedly from contemporary spoken Mandarin.

- Coptic, a form of ancient Egyptian, is used by the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and the Coptic Catholic Church.

- Damin, an initiation language of the Lardil in Australia

- Early Modern Dutch is the language of the Statenvertaling, still in use among (ultra-)orthodox Calvinist denominations in the Netherlands.

- Early Modern English is used in some parts of the Anglican Communion and by the Continuing Anglican movement, as well as by a variety of English-speaking Protestants.

- Eskayan in the Philippines

- Etruscan, cultivated for religious and magical purposes in the Roman Empire.

- Ge'ez, the predecessor of many Ethiopian Semitic languages (e.g. Amharic, Tigrinya, Tigre) used as a liturgical language by Ethiopian Jews and by Ethiopian and Eritrean Christians (in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and the Roman Catholic Church).

- Early New High German is used in Amish communities for Bible readings and sermons.

- Gothic, sole East Germanic language which is attested by significant texts, usually considered to have been preserved for the Arian churches, while the Goths themselves spoke vulgar Latin dialects of their areas.

- Koine Greek, the language of early Pauline Christianity and all of its New Testament books. It is today the liturgical language of Greek Christianity. It differs markedly from Modern Greek, but still remains comprehensible for Modern Greek speakers.

- Biblical Hebrew - the languages in which the Hebrew Bible Tanakh/Miqra has been written over time; these differ from today's spoken Hebrew in lexical and grammatical areas. Its closest living descendant is the Temani (Yemenite Hebrew).

- Jamaican Maroon Spirit Possession Language, spoken by Jamaican Maroons, the descendants of runaway slaves in the mountains of Jamaica, during their "Kromanti Play", a ceremony in which the participants are said to be possessed by their ancestors and to speak as their ancestors did centuries ago.

- Judeo-Spanish, used in some Donmeh prayers.

- Kallawaya, a secret medicinal language used in the Andes

- Kannada is the language of Vachana sahitya, which is a literature of Lingayatism. Some literature of this religion is also in Telugu and Sanskrit.

- Korean is the language preferred by the Unification Church. Church founder Sun Myung Moon has instructed all Unification Church members to learn Korean because "Korean is the language closest to God's Heart, and the future world language will be Korean".

- Kurdish is the language of the Yazidi and Yârsân.

- Ladino, used in translations of the Hebrew Bible and some Sephardic Jewish communities.[5]

- Ecclesiastical Latin is the liturgical language of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church. It is also the official language of the Holy See.

- Old Latin was used in various prayers in Roman paganism, such as the Carmen Arvale and Carmen Saliare. These texts were unintelligible to classical Latin speakers and remain somewhat obscure to scholars even today.

- Manchu was the language used in Manchu shamanic rituals.

- Mandaic, an Aramaic language, in Mandaeanism

- Medefidrino, a constructed language of Nigeria

- Classical Mongolian was used alongside Classical Tibetan as sacred languages of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia.

- Historian Robert Beverley, Jr., in his History and Present State of Virginia (1705), wrote that the "priests and conjurers" of the Virginia Indian tribes "perform their adorations and conjurations" in the Occaneechi language, much "as the Catholics of all nations do their Mass in the Latin". He also stated the language was widely used as a lingua franca "understood by the chief men of many nations, as Latin is in many parts of Europe"—even though, as he says, the Occaneechis "have been but a small nation, ever since those parts were known to the English". Scholars believe that the Occaneechi spoke a Siouan dialect similar to Tutelo.

- Palaic and Luwian, cultivated as a religious language by the Hittites.

- Pali, the original language of Theravada Buddhism.

- Some Portuguese and Latin prayers are retained by the Kakure Kirishitan (Hidden Christians) of Japan, who recite it without understanding the language.

- Sant Bhasha, a mélange of archaic Punjabi and several other languages, is the language of the Sikh holy scripture Guru Granth Sahib.[7] It is different from the various dialects of Punjabi that exist today.

- Sanskrit, the tongue of the Vedas and other sacred texts of Hinduism as well as the original language of Mahayana Buddhism and a language of Jainism.

- Old Church Slavonic, which was the liturgical language of the Slavic Eastern Orthodoxy, and the Romanian Orthodox Church

- Church Slavonic is the current liturgical language of the Russian Orthodox Church, Orthodox Church of Serbia, Orthodox Church of Bulgaria and the Macedonian Orthodox Church and certain Byzantine (Ruthenian) Eastern Catholic churches.

- Sumerian, cultivated and preserved in Assyria and Babylon long after its extinction as an everyday language.

- Syriac, a type of Aramaic, is used as a liturgical language by Syriac Christians who belong to the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church, and Maronite Church.

- Tamil is the language of the Shaiva (Devaram) and Vaishnava (Divya Prabhandham) scriptures. It is an inalienable part of temple ritual in Tamil Nadu and other South Indian temples especially during the time of vaikunta ekadasi in vaishnava .

- Classical Tibetan, known as Chhokey in Bhutan, the sacred language of Tibetan Buddhism

- Various Native American languages are cultivated for religious and ceremonial purposes by Native Americans who no longer use them in daily life.

- Yoruba (known as Lucumi in Cuba), the language of the Yoruba people, brought to the New World by African slaves, and preserved in Santería, Candomblé, and other transplanted African religions. The Yoruba descendents in these communities, as well as non-descendents that have adopted one of the Yoruba-based religions in the diaspora, no longer speak any of the Yoruba dialects with any level of fluency. And the liturgical usage also reflects the compromise of the language whereby there isn't an understand of correct grammar nor proper intonation. Spirit possession by the Yoruba deities in Cuba shows that the deity manifested in the devotee at a Cuban orisa ceremony delivers messages to the faithful in bozal, a type of Spanish-based creole with some words of Yoruba language as well as those of Bantu origin with an inflection similar to the way Africans would speak as they were learning Spanish during enslavement.

References

- ↑ Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2003), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 1, London: Macmillan, p. 137.

- ↑ Salvucci, Claudio R. 2008. The Roman Rite in the Algonquian and Iroquoian Missions. Merchantville, NJ:Evolution Publishing. See also http://mysite.verizon.net/driadzbubl/IndianMasses.html

- ↑ Cutler, Norman (1987). Songs of Experience: The Poetics of Tamil Devotion. Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Kanchan Sinha, Kartikeya in Indian art and literature, 1979,Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan.

- 1 2 EL LADINO: Lengua litúrgica de los judíos españoles, Haim Vidal Sephiha, Sorbona (París), Historia 16 - AÑO 1978:

- ↑ "Clearing up Ladino, Judeo-Spanish, Sephardic Music" Judith Cohen, HaLapid, winter 2001; Sephardic Song Judith Cohen, Midstream July/August 2003

- ↑ Nirmal Dass (2000). Songs of Saints from Adi Granth. SUNY Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7914-4684-3. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

Any attempt at translating songs from the Adi Granth certainly involves working not with one language, but several, along with dialectical differences. The languages used by the saints range from Sanskrit; regional Prakrits; western, eastern and southern Apabhramsa; and Sahaskrit. More particularly, we find sant bhasha, Marathi, Old Hindi, central and Lehndi Panjabi, Sindhi and Persian. There are also many dialects deployed, such as Purbi Marwari, Bangru, Dakhni, Malwai, and Awadhi.