Marshall Court

| Marshall Court | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Established | 1801 |

| Dissolved | 1835 |

| Country | United States |

| Location |

Old Supreme Court Chamber United States Capitol Washington, D.C. |

| Number of positions |

6 (1801-1807) 7 (1807-1835) |

The Marshall Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1801 to 1835, when John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Roger Taney took office. The Marshall Court played a major role in increasing the power of the judicial branch, as well as the power of the national government.[1]

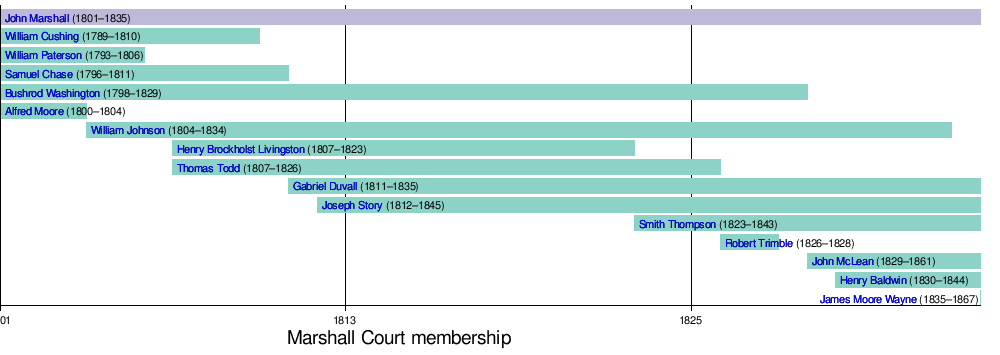

Membership

The Marshall Court began in 1801, when President John Adams appointed Secretary of State John Marshall to replace the retiring Oliver Ellsworth. Marshall was nominated after former Chief Justice John Jay refused the position; many in Adams's party advocated the elevation of Associate Justice William Paterson, but Adams refused to nominate someone close to his intra-party rival, Alexander Hamilton.[2] The Marshall Court began with Marshall and five Associate Justices from the Ellsworth Court: William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, Bushrod Washington, and Alfred Moore. President Thomas Jefferson appointed William Johnson to replace Moore after Moore resigned in 1804. In 1807, Jefferson appointed two more justices, as Paterson died and Congress added a new seat for an Associate Justice. Jefferson successfully nominated Henry Brockholst Livingston and Thomas Todd. President James Madison appointed Gabriel Duvall and Joseph Story in 1811 and 1812, replacing Cushing and Chase. Madison had nominated Alexander Wolcott to replace Cushing, but the Senate voted him down. President James Monroe appointed Smith Thompson to succeed Livingston in 1823. President John Quincy Adams successfully nominated Robert Trimble to replace Todd in 1826. Trimble died in 1828, and Adams's nomination of John J. Crittenden was blocked by the Senate. Instead, Trimble was succeeded by John McLean, who was appointed by Andrew Jackson. In 1830, Jackson appointed Henry Baldwin to replace Washington, and in 1834, Jackson appointed James Moore Wayne to replace Johnson. In 1835, Jackson nominated Roger Taney to succeed the retiring Duvall, but the nomination was denied by the Senate. Marshall died in 1835, and Taney was instead nominated to replace Marshall as Chief Justice. Taney was confirmed in 1836, beginning the Taney Court.

Chief Justice Associate Justice

Political role

Marshall took office during the final months of John Adams's presidency, and his appointment entrenched Federalist power within the judiciary. The Judiciary Act of 1801 also established several new court positions that were filled by President Adams, but the act was largely repealed after the Democratic-Republicans took control of the government in the 1800 elections. Regardless, Marshall was the last justice appointed by a president of the Federalist Party, and the last justice appointed by a president who was not a member of the Democratic-Republicans or Democratic Party until the 1840s. Although Democratic-Republicans had appointed a majority of the justices after 1811, Marshall's philosophy of a relatively strong national government continued to guide the decisions of the Supreme Court until his death.[3] The Democratic-Republicans attempted to impeach Justice Chase for overtly campaigning for John Adams's re-election, possibly impeding the independence of the Supreme Court, but the attempt failed after defections from within the party.[4] Marshall's philosophy differed dramatically from that of some of his contemporaries outside the court, including Spencer Roane, who wrote a series of essays arguing that state courts should have the final say in most matters.[5] Marshall's domination of the courts ensured that the federal government would retain relatively strong powers, despite the political domination of Jeffersonians after 1800.[6] Marshall's opinions also helped to reinforce the independent power of the Supreme Court as a check on Congress,[7] and laid some of the philosophical foundations of the Whig Party, which arose in the 1830s.[8] Due to the Marshall Court's many accomplishments, President Adams referred to his appointment of Marshall as the "proudest act of his life."[7]

Rulings of the Court

The Marshall Court issued several major rulings during its tenure, including:[9]

- Marbury v. Madison (1803): In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court struck down Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, since it extended the court's original jurisdiction beyond what was established in Article III of the United States Constitution. In so doing, the court held that a law written by Congress was unconstitutional, firmly establishing the Supreme Court's power of judicial review. Although judicial review had a long history in American and British thought, Marbury was nonetheless extremely important for establishing the Supreme Court's independence and ability to strike down laws of Congress that it deemed unconstitutional.[10]

- Fletcher v. Peck (1810): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court held that the state of Georgia had violated the Contract Clause by voiding land grants in the Yazoo lands that had been influenced by bribery. The case marked the first time that the court struck down a state law as unconstitutional.[11]

- Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1817): In an opinion written by Justice Story, the court held that it had held appellate power over state courts in regards to the United States Constitution and federal laws and treaties. The Supreme Court would again uphold this principle in Cohens v. Virginia (1821).[12]

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819): In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court held that the state of Maryland had no power to tax a federal bank (the Second Bank of the United States) operating in Maryland. In so doing, the court upheld Congress's ability to establish the bank, taking a relatively broad view of the Necessary and Proper Clause.[13]

- Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall (with several concurring opinions), the court invalidated New Hampshire's attempts to alter Dartmouth College's charter. The court held that the Contract Clause protects corporations from having contracts interfered with by the states.

- Johnson v. M'Intosh (1823): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court held that private parties could not validly purchase land from Native Americans.

- Gibbons v. Ogden (1824): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court struck down a New York law that had granted a monopoly on steamship operation in the state of New York. In its decision, the court upheld Congress's ability to regulate commerce under the Commerce Clause.[14]

- Worcester v. Georgia (1832): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court voided the state of Georgia's conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that states have no authority to deal with Native American tribes. However, President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the court's prohibition against Georgia's interference in Cherokee affairs.

- Barron v. Baltimore (1833): In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, the court held that the Bill of Rights does not apply to the actions of state governments. The decision would later be largely overruled by the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and subsequent Supreme Court decisions.

For a full list of decisions by the Marshall Court, see lists of United States Supreme Court cases by volume, volumes 5 through 34.

See also

References

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard (1993). A History of the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Schwartz, 32-34

- ↑ Schwartz, 58-59

- ↑ Schwartz, 57-58

- ↑ Schwartz, 54-57

- ↑ Schwartz, 67-68

- 1 2 Haskins, George L. (November 1981). "LAW VERSUS POLITICS IN THE EARLY YEARS OF THE MARSHALL COURT". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 130 (1): 1–2. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Graber, Mark (Fall 1998). "Federalist or Friends of Adams". Studies in American Political Development. 12: 264–265. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Schwartz, 32-68

- ↑ Schwartz, 42-43

- ↑ Schwartz, 43-44

- ↑ Schwartz, 44-45

- ↑ Schwartz, 45-46

- ↑ Schwartz, 47-49