Mary Boleyn

| Mary Boleyn | |

|---|---|

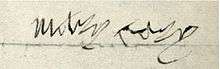

Portrait of Mary Boleyn | |

| Spouse(s) |

William Carey, of Aldenham William Stafford, of Chebsey |

|

Issue | |

| Noble family | Boleyn |

| Father | Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire |

| Mother | Lady Elizabeth Howard |

| Born |

c. 1499/1500 Blickling Hall, Norfolk |

| Died | 19 July 1543 (aged 43–44) |

Mary Boleyn, also known as Lady Mary [1] (c. 1499/1500 – 19 July 1543), was the sister of English queen Anne Boleyn, whose family enjoyed considerable influence during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Mary was one of the mistresses of Henry VIII, from a period of roughly 1521 to 1526. It has been rumoured that she bore two of the king's children, though Henry did not acknowledge either of them as he had acknowledged Henry FitzRoy, his son by another mistress, Elizabeth Blount. Mary was also rumoured to have been a mistress of Henry VIII's rival, King Francis I of France, for some period between 1515 and 1519.[2]

Mary Boleyn was married twice: in 1520 to William Carey, and again, secretly, in 1534, to William Stafford, a soldier from a good family but with few prospects. This secret marriage to a man considered beneath her station angered both Henry VIII and her sister, Queen Anne, and resulted in Mary's banishment from the royal court. She spent the remainder of her life in obscurity. She then died seven years later. Leaving the Boleyn's no heir but Elizabeth I a female was considered unfit to inherit though, or Henry Carey.

Early life

Mary was probably born at Blickling Hall, the family seat in Norfolk, and grew up at Hever Castle, Kent.[3] She was the daughter of a rich diplomat and courtier, Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, by his marriage to Lady Elizabeth Howard, the eldest daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk.

There is no evidence of Mary's exact date of birth, but it occurred sometime between 1499 and 1508. Most historians suggest that she was the eldest of the three surviving Boleyn children.[4] Evidence suggests that the Boleyn family treated Mary as the eldest child; in 1597, her grandson Lord Hunsdon claimed the earldom of Ormond on the grounds that he was the Boleyns’ legitimate heir. Many ancient peerages can descend through female heirs, in the absence of an immediate male heir. If Anne had been the elder sister, the better claim to the title would have belonged to her daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. However, it appears that Queen Elizabeth offered Mary's son, Henry, the earldom as he was dying, although he declined it. If Mary had been the eldest Boleyn sister, Henry would have inherited the title upon his grandfather's death without a new grant from the queen.[5] There is more evidence to suggest that Mary was older than Anne. She was married first, on 4 February 1520;[6] an elder daughter was traditionally married before her younger sister. In 1532, when Anne was created Marchioness of Pembroke, she was referred to as "one of the daughters of Thomas Boleyn". Were she the eldest, that status would probably have been mentioned. Most historians now accept Mary as the eldest child, placing her birth some time in 1499.[7]

Mary was brought up with her brother George and her sister Anne by a French governess at Hever Castle in Kent. She was given a conventional education deemed essential for young ladies of her rank and status, which included the basic principles of arithmetic, grammar, history, reading, spelling, and writing. In addition to her family genealogy, Mary learned the feminine accomplishments of dancing, embroidery, etiquette, household management, music, needlework, and singing, and games such as cards and chess. She was also taught archery, falconry, riding, and hunting.[8]

It is possible that Mary began her education abroad and spent time as a companion to Archduchess Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands, but it is believed that it was Anne who was chosen to go to the court of the Archduchess.[9] Mary remained in England for most of her childhood, until she was sent abroad in 1514 around the age of fifteen when her father secured her a place as maid-of-honour to the King’s sister, Princess Mary, who was going to Paris to marry King Louis XII of France.

After a few weeks, many of the Queen's English maids were sent away, but Mary was allowed to stay, probably due to the fact that her father was the new English ambassador to France. Even when Queen Mary left France after she was widowed on 1 January 1515, Mary remained behind at the court of Louis' successor, Francis I and his queen consort Claude.[10]

Royal affair in France

Mary was joined in Paris by her father, Sir Thomas, and her sister, Anne, who had been studying in France for the past year. During this time Mary is supposed to have embarked on several affairs, including one with King Francis himself.[11][12] Although some historians believe that the reports of her sexual affairs are exaggerated, the French king referred to her as "The English Mare", "my hackney",[12] and as "una grandissima ribalda, infame sopra tutte" ("a great slag, infamous above all").[11][13][14]

She returned to England in 1519, where she was appointed a maid-of-honour to Catherine of Aragon, the queen consort of Henry VIII.[15]

Royal mistress

Soon after her return, Mary was married to William Carey, a wealthy and influential courtier, on 4 February 1520; Henry VIII was a guest at the couple's wedding.[16] At some point, Mary became Henry's mistress; the exact date is unclear, but it probably began some time in 1521.[17] Her first child, Catherine, was born in 1524. Henry's involvement is believed to have ended prior to the birth of Mary's second child, Henry Carey, in March 1526, at which point his involvement would have lasted for five years.[17][18]

During this time, it was rumoured that one, or both, of Mary's children were fathered by the king.[19][20] One witness noted that Mary's son, Henry Carey, bore a resemblance to Henry VIII.[17] John Hale, Vicar of Isleworth, some ten years after the child was born, remarked that he had met a 'young Master Carey' who was the king's purported bastard child.[17] No other contemporary evidence exists to support the argument that Henry was the king’s biological son.

Henry VIII's wife, Catherine of Aragon, had first been married to Henry's elder brother Arthur when he was a little over fifteen years old, but Arthur had died just a few months later. Henry later used this to justify the annulment of his marriage to Catherine, arguing that her marriage to Arthur had created an affinity between Henry and Catherine; as his brother's wife, under canon law she became his sister. When Mary's sister Anne later became Henry's wife, this same canon law might also support that a similar affinity had been created between Henry and Anne due to his earlier liaison with Mary. In 1527, during his initial attempts to obtain a papal annulment of his marriage to Catherine, Henry also requested a dispensation to marry Anne, the sister of his former mistress.[21]

Sister’s rise to power

Anne had returned to England in January 1522; she soon joined the royal court as one of Queen Catherine's maids-of-honour. Anne achieved considerable popularity at court, although the sisters already moved in different circles and were not thought to have been particularly close.

Although Mary was alleged to have been more attractive than her sister, Anne seems to have been more ambitious and intelligent. When the king took an interest in Anne, she refused to become his mistress, being shrewd enough not to give in to his sexual advances and returning his gifts.[22] By the middle of 1527, Henry was determined to marry her. This gave him further incentive to seek the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. A year later, when Mary's husband died during an outbreak of sweating sickness, Henry granted Anne Boleyn the wardship of her nephew, Henry Carey. Mary's husband had left her with considerable debts, and Anne arranged for her nephew to be educated at a respectable Cistercian monastery. Anne also interceded to secure her widowed sister an annual pension of £100.[23]

Second marriage

In 1532, when Anne accompanied Henry to the English Pale of Calais on his way to a state visit to France, Mary was one of her companions. Anne was crowned queen on 1 June 1533 and on 7 September gave birth to Henry's daughter Elizabeth, who later became Queen Elizabeth I. In 1534, Mary secretly married an Essex landowner's younger son: William Stafford (later Sir William Stafford). Since Stafford was a soldier, his prospects as a second son so slight, and his income so small, many believed the union was a love match.[24] When Mary became pregnant, the marriage was discovered. Queen Anne was furious, and the Boleyn family disowned Mary. The couple were banished from court.

Mary's financial circumstances became so desperate that she was reduced to begging the king’s adviser Thomas Cromwell to speak to Henry and Anne on her behalf. She admitted that she might have chosen "a greater man of birth and a higher" but never one that should have loved her so well, nor a more honest man. And she went on, "I had rather beg my bread with him than to be the greatest queen in Christendom. And I believe verily ... he would not forsake me to be a king". Henry, however, seems to have been indifferent to her plight. Mary asked Cromwell to speak to her father, her uncle, and her brother, but to no avail. It was Anne who relented, sending Mary a magnificent golden cup and some money, but still refused to reinstate her position at court. This partial reconciliation was the closest the two sisters attained; it is not thought that they met after Mary's exile from the king's court.

Mary's life between 1534 and her sister's execution on 19 May 1536 is difficult to trace. There is no record of her visiting her parents, and no evidence of any correspondence with, or visits to, her sister Anne or her brother George when they were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Like their uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, she may have thought it wise to avoid association with her now-disgraced relatives.

Letters Patent by Henry VIII, referenced in Alison Weir's 2011 book, Mary Boleyn: 'The Great and Infamous Whore', reveal that Mary had been posthumously accorded the title Dame Mary Stafford. Her husband, William, had been knighted on 23 September 1545, with Mary having died in 1543, two years earlier. These letters indicate that, in their final years, the couple had remained outcasts from the court and in 1542 were dealing with family real estate concerns, living in retirement at Rochford Hall in Essex, which was owned by the Boleyns.[25] If the couple had had children, none of them survived infancy. After Anne’s execution, their mother retired from court, dying in seclusion just two years later. Her father, Thomas, died a year after his wife. Following the deaths of her parents, Mary inherited some property in Essex. She seems to have lived out the rest of her days in obscurity and relative comfort with her second husband. Hever Castle, home of the Boleyns, was returned to the Crown at the death of her father, Thomas. When Henry VIII sold it, he sent Mary some of the proceeds, though he had given her nothing of value at the end of their affair when it would have been expected for him to do so. Mary died of unknown causes, on 19 July 1543, in her early forties.

Issue

Mary married William Carey (1500 – 22 June 1528) but it has long been thought that one or both of Mary Boleyn's older children were fathered by Henry VIII.[26][27] Some writers, such as Alison Weir, question whether Henry Carey (Mary's son) was fathered by the King,[28] while others, such as Dr. G.W. Bernard (author of The King's Reformation) and Joanna Denny (author of Anne Boleyn: A New Life of England's Tragic Queen and Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy) argue that he may have been.

When comparing portraits, it has been argued that Catherine Carey and her daughters Lettice, Anne, and Elizabeth Knollys all bore a marked resemblance to Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. If Catherine was indeed born in June 1524, then this would point to her being fathered by Henry VIII, since Mary Boleyn's affair with him appears to have begun around 1522 and ended in the early summer of 1525. This date also makes it possible for Henry Carey to have been conceived just before the end of the affair. A close reading of the Letters and Papers (a collection of surviving documents from the period) seems to pinpoint Henry Carey's birth to March 1526.[29][30]

Also in favour of the king's paternity of Mary's son is that the child was named Henry, and at least one observer noted that Mary's son bore a resemblance to Henry VIII. That person was John Hales, vicar of Isleworth, who some ten years after Mary's son was born remarked that he had met "young Master Carey," who some believed was the king's son. There is no other existing contemporary evidence that Henry Carey was the king’s biological child.

Mary Boleyn was the mother of:

- Catherine Carey (1524 – 15 January 1569). Maid-of-honour to both Anne of Cleves and Catherine Howard, she married a Puritan, Sir Francis Knollys, Knight of the Garter, by whom she had issue. She later became chief lady of the bedchamber to her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. One of her daughters, Lettice Knollys, became the second wife of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, the favourite of Elizabeth I.

- Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon (4 March 1526 – 23 July 1596). He was ennobled by Queen Elizabeth I shortly after her coronation, and later made a Knight of the Garter. When he was dying, Elizabeth offered Henry the Boleyn family title of Earl of Ormond, which he had long sought, but at that point, declined. He was married to Anne Morgan, by whom he had issue.

Mary's marriage to William Stafford (d. 5 May 1556) may have resulted in the birth of two further children:[31]

- Edward Stafford (1535–1545).

- Anne Stafford (b. 1536?–?), probably named in honour of Mary's sister, Queen Anne Boleyn.

Depictions in fiction

Mary was depicted in the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days, and was played by Valerie Gearon.

She was also depicted in the Showtime television series The Tudors (2007–2010), where she was played by Perdita Weeks.

A fictionalised form of her character also features prominently in the novels:

- Brief Gaudy Hour: A Novel of Anne Boleyn by Margaret Campbell Barnes (1949)

- Anne Boleyn by Evelyn Anthony (1957)

- The Concubine: A Novel Based Upon the Life of Anne Boleyn by Norah Lofts (1963)

- Anne, the Rose of Hever by Maureen Peters (1969)

- Anne Boleyn by Norah Lofts (1979)

- Mistress Anne: The Exceptional Life of Anne Boleyn by Carolly Erickson (1984)

- The Lady in the Tower by Jean Plaidy (1986)

- I, Elizabeth: the Word of a Queen by Rosalind Miles (1994)

- The Secret Diary of Anne Boleyn by Robin Maxwell (1997)

- Dear Heart, How Like You This? by Wendy J. Dunn (2002)

- Doomed Queen Anne by Carolyn Meyer (2002)

- Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel (2009)

Mary has been the central character in three novels based on her life:

- Court Cadenza (later published under the title The Tudor Sisters) by British author Aileen Armitage (Aileen Quigley) (1974)

- The Last Boleyn by Karen Harper (1983)

- The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory (2001)

Philippa Gregory later nominated Mary as her personal heroine in an interview to the BBC History Magazine. Her novel was a bestseller and spawned five other books in the same series. However, it was controversial, since many historians found the work inaccurate in regards to historical events and individual characterizations.[12] For example, Gregory characterizes Anne, not Mary, as the elder sister, and makes no mention of Mary's relationships prior to her affair with Henry.[12][32]

The Other Boleyn Girl was made into a BBC television drama in January 2003, starring Natascha McElhone as Mary and Jodhi May as Anne.

A Hollywood film version of the book was released in February 2008, with Scarlett Johansson as Mary and Natalie Portman as Anne and Eric Bana as King Henry VIII. In Wolf Hall, Boleyn is portrayed by Charity Wakefield.

Non-fiction

Mary is also a subject in three non-fiction books:

- Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings by Alison Weir (2011)

- The Mistresses of Henry VIII by Kelly Hart (2009)

- Mary Boleyn: The True Story of Henry VIII's Mistress by Josephine Wilkinson (2010)[33]

Ancestry

References

- ↑ "Katherine Knollys". Westminster Abbey – Founded 960. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Katherine Knollys' tombstone in Westminster Abbey reads thus: "This Lady Knollys and the Lord Hundesdon her brother were the childeren of William Caree Esquyer, and of the Lady Mary his wiffe one of the doughters and heires to Thomas Bulleyne Erle of Wylshier [Wiltshire] and Ormond. Which Lady Mary was sister to Anne Quene of England wiffe to Kinge Henry the Eyght father and mother to Elizabeth Quene of England”.

- ↑ Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII, X, no.450.

- ↑ Letters of Matthew Parker, p.15.

- ↑ Ives, p. 17; Fraser, p. 119; Denny, p. 27. All three scholars argue that Mary was the eldest of the three Boleyn children.

- ↑ Hart, Kelly (1 June 2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII (First ed.). The History Press. ISBN 0-7524-4835-8.

- ↑ The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn: The Most Happy by Eric Ives

- ↑ Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1992), p. 119

- ↑ Wilkinson, Josephine (2009). "The Early years, 1500–1514". Mary Boleyn: The True Story of Henry VIII's Mistress. Amberley. p. 13.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2011). Mary Boleyn: Mistress of Kings. Ballantine Books. Footnote 29.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2002). Henry VIII: The King and His Court. Ballantine Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-345-43708-2.

- 1 2 Weir, Alison (2002). "Henry VIII: The King and His Court", p. 216. New York: Ballantine Books

- 1 2 3 4 von Tunzelmann, Alex (6 August 2008). "The Other Boleyn Girl: Hollyoaks in fancy dress". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Charles Carlton, Royal Mistresses (1990)

- ↑ Denny, p. 38

- ↑ Marie-Louise Bruce, p. 13

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2002). Henry VIII: The King and His Court. Ballantine Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-345-43708-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Weir, Alison (2002). "Henry VIII: The King and His Court", p. 216-217. New York: Ballantine Books

- ↑ See Letters & Papers viii.567 and Ives, pp. 16 – 17.

- ↑ Ives, Eric William (2004). "The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn", p. 369 (note 75). Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (1991). "The Six Wives of Henry VIII", p. 133-134. New York: Grove Weidenfeld

- ↑ Kelly, Henry Angsar: The Matrimonial Trials of Henry VIII pp42 ff

- ↑ Weir, p. 160

- ↑ Karen Lindsey, p. 73

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2011). Mary Boleyn: Mistress of Kings. Ballantine Books. Footnote 10.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (20 September 2012). Mary Boleyn: 'The Great and Infamous Whore'. Vintage. p. 226. ISBN 9780099546481.

Letters Patent by Henry VIII, referenced in Alison Weir's 2011 book, Mary Boleyn: "The Great and Infamous Whore", reveal that Mary had been posthumously accorded the title Dame Mary Stafford. Her husband, William, had been knighted on 23 September 1545, with Mary having died in 1543, two years earlier. These letters indicate that, in their final years, the couple had remained outcasts from the court and in 1542 were dealing with family real estate concerns, living in retirement at Rochford Hall in Essex, which was owned by the Boleyns.

- ↑ Hart pp.60–63

- ↑ Sally Varlow, "Knollys, Katherine, Lady Knollys (c.1523–1569)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Oxford University Press, October 2006; online edn, January 2009, accessed 11 April 2010

- ↑ Weir. Henry VIII: The King and His Court. p. 216.

- ↑ Public Record Office. Letters & Papers. vol. viii, p.567.

- ↑ Ives. Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Hart p. 118

- ↑ Gregory, Philippa, "The Other Boleyn Girl"

- ↑ ISBN 1-84868-089-9

- ↑ Lady Elizabeth Howard, Anne Boleyn's mother, was the sister of Lord Edmund Howard, father of Catherine Howard (fifth wife of King Henry VIII), making Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard first cousins.

- ↑ Elizabeth Tilney is the paternal grandmother of Catherine Howard.

Further reading

- Weir, Alison. (2011). Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-52133-0

- Wilkinson, Josephine. (2010). Mary Boleyn: The True Story of Henry VIII's Favorite Mistress. Amberley. ISBN 978-1-84868-525-3

- Hart, Kelly. (2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5852-6

- Harper, Karen. (2006). The Last Boleyn: A Novel. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-23790-3

- Lofts, Norah. (1979). Anne Boleyn.

- Gregory, Philippa. (2003). The Other Boleyn Girl. Touchstone. ISBN 0-7432-2744-1

- Adair, Anne. (2011). Mary Boleyn: Sister to Queen Anne Boleyn and Sister in Law to King Henry VIII. Webster's Digital Services. ISBN 978-1-241-00378-4

- Denny, Joanna. (2004). Anne Boleyn: A New Life of England's Tragic Queen. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81540-9

- Fraser, Antonia. (1992). The Wives of Henry VIII. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-14-013293-9

- Bruce, Marie-Louise. (1972). Anne Boleyn

- Ives, Eric.(2004). The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3463-7

- Lindsey, Karen. (1995). Divorced Beheaded Survived: A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-201-40823-2

- Weir, Alison.(1991). The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3683-1