Max Brod

Max Brod (Hebrew: מקס ברוד; May 27, 1884 – December 20, 1968) was a German-speaking Czech Jewish, later Israeli, author, composer, and journalist. Although he was a prolific writer in his own right, he is most famous as the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka. As Kafka's literary executor, Brod refused to follow the writer's instructions to burn his life's work, and had them published instead.

Biography

Max Brod was born in Prague, then part of the province of Bohemia in Austria-Hungary, now the capital of the Czech Republic. At the age of four, Brod was diagnosed with a severe spinal curvature and spent a year in corrective harness; despite this he would be a hunchback his entire life.[1] A German-speaking Jew, he went to the Piarist school together with his lifelong friend Felix Weltsch, later attended the Stephans Gymnasium, then studied law at the German Charles-Ferdinand University (which at the time was divided into a German language university and a Czech language university; he attended the German one) and graduated in 1907 to work in the civil service. From 1912, he was a pronounced Zionist (which he attributed to the influence of Martin Buber) and when Czechoslovakia became independent in 1918, he briefly served as vice-president of the Jüdischer Nationalrat. From 1924, already an established writer, he worked as a critic for the Prager Tagblatt.

In 1939, as the Nazis took over Prague, Brod and his wife Elsa Taussig fled to Palestine. He settled in Tel Aviv, where he continued to write and worked as a dramaturg for Habimah, later the Israeli national theatre, for 30 years. For a period following the death of his wife in 1942, Brod published very few works. He became very close to a couple named Otto and Esther Hoffe, regularly taking vacations with the two and employing Esther as a secretary for many years; it is often presumed that their relationship had a romantic dimension.[1] He would later pass stewardship of the Kafka materials in his possession to Esther in his will. He was additionally supported by his close companion Felix Weltsch. Their friendship lasted 75 years, from the elementary school of the Piarists in Prague to Weltsch's death in 1964.[2] Brod died on December 20, 1968 in Tel Aviv.

Literary career

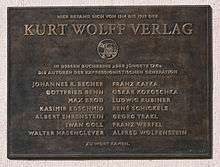

Unlike Kafka, Brod rapidly became a prolific, successful published writer who eventually published 83 titles.[1] His first novel and fourth book overall, Schloss Nornepygge (Nornepygge Castle), published in 1908 when he was only 24, was celebrated in Berlin literary circles as a masterpiece of expressionism. This and other works made Brod a well-known personality in German-language literature. In 1913, together with Weltsch, he published the work Anschauung und Begriff which made him more famous in Berlin and also in Leipzig, where their publisher Kurt Wolff worked.

He unselfishly promoted other writers and musicians. Among his protégés was Franz Werfel, whom he would later fall out with as Werfel abandoned Judaism for Christianity. He would also write at various times both for and against Karl Kraus, a convert from Judaism to Roman Catholicism. His critical endorsement would be crucial to the popularity of Jaroslav Hašek's The Good Soldier Svejk, and he played a crucial role in the diffusion of Leoš Janáček's operas.

Friendship with Kafka

Brod first met Kafka on October 23, 1902, when both were students at Charles University. Brod had given a lecture at the German students' hall on Arthur Schopenhauer. Kafka, one year older, addressed him after the lecture and accompanied him home. "He tended to participate in all the meetings, but up to then we had hardly considered each other," wrote Brod. The quiet Kafka "would have been... hard to notice... even his elegant, usually dark-blue, suits were inconspicuous and reserved like him. At that time, however, something seems to have attracted him to me, he was more open than usual, filling the endless walk home by disagreeing strongly with my all too rough formulations." [3]

From then on, Brod and Kafka met frequently, often even daily, and remained close friends until Kafka's death. Kafka was a frequent guest in Brod's parents' house. There he met his future girlfriend and fiancée Felice Bauer, cousin of Brod's brother-in-law Max Friedmann. After graduating, Brod worked for a time for the post office. The relatively short working hours gave him time to begin a career as an art critic and freelance writer. For similar reasons, Kafka took a job at an insurance agency involved in workmen's accident insurance. Brod, Kafka and Brod's close friend Felix Weltsch constituted the so-called "Der enge Prager Kreis" or "close Prague circle".

During Kafka's lifetime, Brod tried repeatedly to reassure him of his writing talents, of which Kafka was chronically doubtful. Brod pushed Kafka to publish his work, and it is probably owing to Brod that he began to keep a diary. Brod tried, but failed, to arrange common literary projects. Notwithstanding their inability to write in tandem—which stemmed from clashing literary and personal philosophies—they were able to publish one chapter from an attempted travelogue in May 1912, for which Kafka wrote the introduction. It was published in the journal Herderblätter. Brod prodded his friend to complete the project several years later, but the effort was in vain. Even after Brod's 1913 marriage with Elsa Taussig, he and Kafka remained each other's closest friends and confidants, assisting each other in problems and life crises.

Publication of Kafka's work

On Kafka's death in 1924 Brod was the administrator of the estate and preserved his unpublished works from incineration despite what was stipulated in Kafka's will.[4] He defended this course by saying that when Kafka asked him to burn his papers, he told him he would not carry out this wish: "Franz should have appointed another executor if he had been absolutely and finally determined that his instructions should stand."[5] Before even a line of Kafka's most famous work had been made public, Brod had already praised him as "the greatest poet of our time", ranking with Goethe or Tolstoy. As Kafka's works were posthumously published (The Trial arrived in 1925, followed by The Castle in 1926 and Amerika in 1927), this early positive assessment was bolstered by more general critical acclaim.[1]

When Brod fled Prague in 1939, he took with him a suitcase of Kafka's papers, many of them unpublished notes, diaries, sketches, and so forth.[1] Although some of these materials were later edited and published in 6 volumes of collected works, much of them remained unreleased. Upon his death, this trove of materials was passed to Esther Hoffe, who maintained most of them until her own death in 2007 (one original manuscript of The Trial was auctioned in 1988 for $2 million).[1] Due to certain ambiguities regarding Brod's wishes, the proper disposition of the materials is now being litigated. On one side is the National Library of Israel, which believes that Brod passed the papers to Esther as an executor of his actual intent to have the papers donated to the institution. On the other side are Esther's daughters, who claim that Brod passed the papers to their mother as a pure inheritance which should be theirs. The sisters have announced their intention to sell the materials to the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, Germany.[1]

Published works

.jpg)

- Schloß Nornepygge (Nornepygge Castle, 1908)

- Weiberwirtschaft (Woman's Work, 1913)

- Über die Schönheit häßlicher Bilder (On the Beauty of Ugly Pictures, 1913)

- Die Höhe des Gefühls (The Height of Feeling, 1913)

- Anschauung und Begriff: Grundzüge eines Systems der Begriffsbildung, 1913 (together with Felix Weltsch)-->

- Tycho Brahes Weg zu Gott (Tycho Brahe's Path to God 1915)

- Heidentum, Christentum, Judentum: Ein Bekenntnisbuch (Paganism, Christianity, Judaism: A Credo, 1921)

- Sternenhimmel: Musik- und Theatererlebnisse (1923, reissued as Prager Sternenhimmel)

- Reubeni, Fürst der Juden (Reubeni, Prince of the Jews, 1925)

- Zauberreich der Liebe (The Charmed Realm of Love, 1930)

- Biografie von Heinrich Heine (Biography of Heinrich Heine, 1934) Subtitled The Artist in Revolt it was first published in English in 1956 in a revised version translated by Joseph Witriol

- Die Frau, die nicht enttäuscht (The Woman Who Does Not Disappoint, 1934)

- Novellen aus Böhmen (Novellas from Bohemia, 1936)

- Rassentheorie und Judentum (Race Theory and Judaism, 1936)

- Annerl (Annie, 1937)

- Franz Kafka, eine Biographie (Franz Kafka, a Biography, 1937, later collected in Über Franz Kafka, 1974)

- Franz Kafkas Glauben und Lehre (Franz Kafka's Thought and Teaching, 1948)

- Die Musik Israels (The Music of Israel, Tel Aviv, 1951)

- Beinahe ein Vorzugsschüler, oder pièce touchée: Roman eines unauffälligen Menschen (Almost a Gifted Pupil, 1952)

- Die Frau, nach der man sich sehnt (The Woman For Whom One Longs, 1953)

- Rebellische Herzen (Rebellious Hearts, 1957)

- Verzweiflung und Erlösung im Werke Franz Kafkas (Despair and Redemption in the Works of Franz Kafka, 1959)

- Beispiel einer deutsch-jüdischen Symbiose (An Example of German-Jewish Symbiosis, 1961)

- Die verkaufte Braut, translation of the Czech libretto of Prodaná nevěsta (The Bartered Bride, a comic opera by Bedřich Smetana), and numerous other translations of Czech opera libretti

- Über Franz Kafka, (Fischer, Frankfurt am Main, 1974)

Music

Brod's musical compositions are little known, even compared to his literary output. They include songs, works for piano and incidental music for his plays. He translated some of Bedřich Smetana's and Leoš Janáček's operas into German, and wrote the first book on Janáček (first published in Czech in 1924). He authored a study of Gustav Mahler, Beispiel einer deutsch-jüdischen Symbiose, in 1961. Max had studied Orchestration under Alexander Uriah Boskovich.

Awards

In 1948, Brod was awarded the Bialik Prize for literature.[6] In 1965, Brod was awarded the Honor Gift of the Heinrich Heine Society in Düsseldorf, Germany.[7]

Selected filmography

- The Woman One Longs For (1929)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Batuman, Elif (September 22, 2010), "Kafka's Last Trial", New York Times Magazine

- ↑ Where are the missing index cards

- ↑ Brod, Max. Über Franz Kafka'.' p 45)

- ↑ Butler, Judith (March 3, 2011). "Who Owns Kafka". London Review of Books. 33 (5): 3–8. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ Postscript to the first edition of The Trial (1925)

- ↑ "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004, Tel Aviv Municipality website (in Hebrew)" (PDF).

- ↑ "Heinrich-Heine-Ehrengabe 1965-2012, Heinrich Heine Society (in German)".

Further reading

- Kayser, Werner, Max Brod, Hans Christians, Hamburg, 1972 (in German)

- Pazi, Margarita (Ed.): Max Brod 1884–1984. Untersuchungen zu Max Brods literarischen und philosophischen Schriften. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, 1987 (in German)

- Lerperger, Renate, Max Brod. Talent nach vielen Seiten (exhibit catalog), Vienna, 1987 (in German)

- Wessling, Berndt W. Max Brod: Ein Portrait. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin, Cologne and Mainz, 1969. New edition: Max Brod: Ein Portrait zum 100. Geburtstag, Bleicher, Gerlingen, 1984 (in German)

- Bärsch, Claus-Ekkehard, Max Brod im Kampf um das Judentum. Zum Leben und Werk eines deutsch-jüdischen Dichters aus Prag. Passagen Verlag, Wien, 1992.

- Vassogne, Gaelle, Max Brod in Prag: Identität und Vermittlung, Niemeyer, Conditio Judaica 75, 2009 (in German).

- The Modern Hebrew Poem Itself (2003), ISBN 0-8143-2485-1

- Barbora Šrámková: Max Brod und die tschechische Kultur. Arco Verlag, Wuppertal 2010, Arco Wissenschaft Band 17; ISBN 978-3-938375-27-3.

- Christoph Schult (2009-09-28). "The Trial Fight for Kafka's Papers Winds through Israeli Courts". Der Spiegel.