Mischa Portnoff

Mischa Portnoff (August 29, 1901 – May 15, 1979) was a German-born American composer and teacher.

Introduction

German-born American composer and teacher Mischa Portnoff’s distinctive gift as a musician was the breadth of his mastery. His classical compositions, ranging from works for solo piano to symphony orchestra, blended romantic passion with contemporary innovation. His lighter music was performed both on the Broadway stage and in Hollywood films. Mischa’s publications for piano students introduced innovative approaches to instruction and learning; they included material representative of different eras and cultures, as well as numerous arrangements of hit show tunes. His talent as a young pianist led to successful concert tours throughout Europe and North America. Mischa was born in Berlin in 1901. At the age of eight, he began learning to play the piano from his father, Leo Portnoff, a well known violinist and composer. He later studied with Leo and others at Berlin's Stern Conservatory, where Leo taught from 1906 to 1915. He completed his formal studies spending two years at the Swedish Royal Academy of Music, mastering piano technique, theory and composition.[1]

Professional life

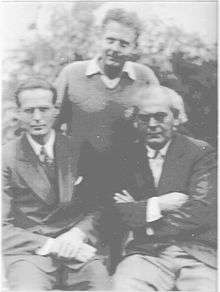

In 1918, Mischa, already at seventeen a virtuoso pianist, and his older brother, accomplished violinist Vassily Portnoff, embarked on a concert tour of Denmark, Sweden, Norway and England. Crossing the Atlantic, they performed throughout Canada and the United States. The brothers’ musical aspirations eventually led them to New York City, the then-uncontested hub of American musical creativity. Leo, their father, had emigrated to the U.S. in 1922, where he taught in New York for eleven years before becoming a professor of violin and composition at the University of Miami in Florida.[2]

In 1925, putting touring behind them, the Portnoff brothers opened a music studio in Brooklyn. Here, with a piano readily at hand, Mischa turned his attention to teaching and to exploring his own musical ideas. For critical evaluation during the development of his more highly challenging compositions, he relied upon his father, who remained an influence and valued adviser throughout his life.[3]

Mischa initially focused on compositions for two pianos, a medium that he believed offered many more creative possibilities than had thus far been explored.[4] His works were heard by audiences in American and European concert halls and were broadcast on network radio, performed by duo-piano teams Pierre Luboshutz and Genia Neminoff, and Ethel Bartlett and Rae Robertson. Concerto Quasi una Fantasia (Unaccompanied), his first extended work, premiered in 1937 performed by Bartlett and Robertson in New York’s Town Hall. It was well received by New York Times music critic "N.S." who wrote this review:

Conceived in the modern idiom, it reveled in a melodic flow not usually encountered in compositions of its dissonant genre . . . There was rugged strength in the first and last divisions, while the slow movement, which harkened back to Debussy (via Gershwin), Albeniz and Ravel, served to give a poetic touch to the whole.[5]

The Bartlett and Robertson duo subsequently performed the concerto in several European cities.[6] Upon hearing a performance of the work at a private reception, John Barbirolli (not yet Sir John), then conductor of the New York Philharmonic, wrote in a letter to Portnoff: "I have not been moved by any new work for a long time as I was by the work Ethel and Rae played for me. One feels real gratitude that such talents as yours are still to be found." [7] This marked the beginning of a three-year collaborative relationship that was supportive of Mischa's work on his most ambitious composition, a concerto for piano and full orchestra.

In 1940, Barbirolli wrote to the brilliant pianist Nadia Reisenberg asking her to "introduce to the public an excellent new piano concerto." [8] Reisenberg, already appreciated by audiences of New York City’s classical radio broadcasts,[9] agreed, and on February 23, 1941 she performed Mischa’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at Carnegie Hall.[10] New York Times music critic Olin Downes reviewed the performance:

John Barbirolli, in the course of one of the best concerts he has conducted here, led the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra yesterday afternoon in Carnegie Hall in the first performance of Mischa Portnoff’s Piano Concerto. The solo part was played by Nadia Reisenberg. The performance was received with prolonged applause. Miss Reisenberg must have gratified the composer, who appeared on the platform with her after the performance, by the virtuosity and command that she showed in her mastery of a piano part that called not merely for physical deeds of derring do, but also for musical thinking of a highly concentrated kind. The complexities of her task did not blind her at any time to the essential proportions of the music.[11]

Musicologist David Ewen described the Concerto’s harmonic and rhythmic structure as "clearly the work of a 20th century composer, but also expressive of a romantic spirit." [12] The Barbirolli Society’s 2008 compact disc includes the Concerto, and the liner notes describe it as "...a dazzlingly effective work, with extremely virtuosic writing for the soloist, composed in a style perhaps best described as a mixture of the then-contemporary music of Prokofiev and Shostakovitch rather than, say, that of Stravinsky," further noting that the work "...surely does not deserve the neglect that has befallen it." [13] Nothing found in family or public archives explains that neglect.

For whatever reasons, the concerto was never again performed. Mischa was in no way prepared to give up on composing, but the commitments inherent in producing major orchestral works and the uncertainty of them as a source of income were incompatible with supporting a family. Mischa turned to creating briefer compositions for solo piano, an endeavor that could fit around an active schedule of teaching.

In 1947, Mischa received a call from Hollywood’s Paramount music director Boris Morros asking whether he and Wesley could compose a rhapsody for the climax of the film Carnegie Hall. Bernardo Segall (1911-1993), a Brazilian classical pianist and friend of Mischa’s, had established a career in Hollywood films; most likely it was he who referred Morros to the brothers. The rhapsody was to be performed by the New York Philharmonic, with Harry James as trumpet soloist. The catch was that the film was already in production and the music was needed within three days. Somehow, the brothers pulled that off.[14] In the film, during The 57th Street Rhapsody, Mischa’s hands are shown playing; unfortunately, there’s no record of whether or not it is his performance that we hear.[15] (More recently, in a reprise of sorts, a more light-hearted tune that Mischa composed in 1931 played throughout the conclusion of the 2005 Russell Crowe depression-era film, Cinderella Man.)[16]

In 1950, Mischa was once more drawn into a major compositional commitment by the opportunity to create a score for a musical adaptation of Donagh MacDonagh's verse play, Happy as Larry. Burgess Meredith would direct and star in the production, which also featured opera singer Marguerite Piazza in her Broadway debut Irwin Corey and Gene Barry. Larry opened January 6, 1950 at Broadway’s Coronet Theater[[17]] to widely divergent reviews. Brooks Atkinson, the most authoritative theater critic of his times, dismissed it as "an ordeal," but gave a nod to the Portnoffs’ songs, calling them "eccentric" and "charming." [18] William Saroyan, on the other hand, appraised the production as one of the two "most daring, effective, meaningful, and satisfying plays of our time." [19] Louis Sheaffer's review in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle comments on the polarization: "Playgoers who like their fare to fall into neat conventional patterns, easily labeled, may be disconcerted by Happy as Larry, but the more adventurous ones will enjoy it." Sheaffer went on to highlight the music:

It is time now to mention the Portnoff brothers’ score, for it is one of the show’s brightest assets. Best known in longhair circles for their serious compositions, Happy as Larry reveals them as equally at home on Broadway. Writing in a variety of moods, they have contributed ear-caressing ballads . . . [and] others zingy with spirit. Theirs is a brilliantly resourceful contribution.[20]

In spite of the non-musical production having been a hit in London, after three performances in New York, McDonagh’s Happy as Larry closed on January 7, 1950.* Later that year Mischa went on to compose ballet music for (orchestrated by Don Walker) for a Broadway musical revue, Bless You All, directed by Lehman Engel and starring Valerie Bettis and Pearl Bailey; the cast gave eighty-four performances.

At various times throughout his career, Mischa considered accepting opportunities to teach at a university or to relocate to Hollywood to compose for films, but he could not bring himself to leave the creative vitality of New York City. He remained there, making his living by composing pedagogical material and arranging piano versions of popular show tunes, while maintaining the amount of time he devoted to private teaching, until his death in 1979.[21]

- Atkinson's 1984 New York Times obituary noted: "He frequently scoffed at the notion that he could make or break a play. But there was never any doubt that he had a potent influence over success or failure on stage."

Personal life

Mischa Portnoff was born in Berlin (Germany) on August 29, 1901 to Ukrainian Jewish parents, Leo and Tscharna Portnoff. His brother Vassily (later called "Wesley") was a year older. Their mother died when Mischa was about five, and as an adult he remembered little about her. His father remarried; the brothers were raised primarily by a series of tutors and housekeepers, not uncommon in middle-class German families of the period. In addition to his music studies, Mischa enjoyed sports, particularly swimming and tennis.

As mentioned above, for six successful years, as young musicians, Mischa and Wesley toured Northern Europe and North America, Mischa on piano and Vassily on violin, before settling in New York City. There, they rented an apartment with studio space overlooking Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, just twenty minutes by subway from Manhattan’s concert halls and theaters.

For both brothers, the most unexpected outcome of their American tour followed from a performance in Washington State. In Seattle, Mischa was introduced to the Levine family and their youngest daughter, Marguerite, a piano prodigy. It was soon decided that once the Portnoff brothers were established in New York, Mischa would accept Marguerite as a student. She would live with her sister Ida, an advanced ballet student (and, later, one of the famed Ziegfeld Girls), who had already moved to New York to study with dancer/choreographer Mikhail Fokine. In 1929, Marguerite, then about 16 years old, crossed the country to live with her 19-year-old sister and to continue studying piano.

Eventually, through Mischa, Wesley and Ida Levine also became acquainted, and the couple subsequently married. Three years after taking Marguerite on as a student, Mischa proposed marriage and Marguerite accepted. The two couples lived together until Ida’s untimely death of an illness at age 29. In October 1938, Mischa and Marguerite’s only child, Gregory, was born, and in December of that year Mischa became an American citizen. Wesley, who remained Mischa’s closest friend and sometime colleague, continued living in the family’s home until his death in 1969.

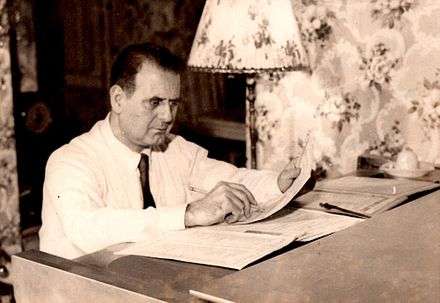

Although Marguerite chose not to pursue a solo career as a pianist, the couple occasionally performed two-piano and four-hand compositions together in public. She taught her own piano students, and when Mischa turned to developing pedagogical material, she took the lead in researching and writing accompanying text (e.g., introductory material, biographical sketches of composers, descriptions of musical forms) and in preparing submissions for publication. Mischa devoted considerable time to music, even apart from working on specific projects and teaching. Seated at the piano, an inch-long ash drooping from a cigarette he had not drawn upon, he would experiment with a phrase until he had created an iteration that pleased him or that fit well into a composition that he had previously written. An eclectic listener, while Brahms remained his favorite composer, Mischa was also captivated by the musicality of the Beatles. He found much pleasure in life beyond music, as well. He was an avid reader of popular fiction (particularly the noir mysteries of the forties) and enjoyed movies and games. Mischa and Marguerite clearly found pleasure one another’s company, walking together in Prospect Park, competing at Scrabble and double solitaire, occasionally having dinner out, attending a dance recital, or spending an evening with long-time friends.

In 1960, the couple’s son Gregory married and, in 1971, moved to Olympia, Washington. Throughout the 1970s, Mischa and Marguerite traveled west to spend summers near their three grandsons. In 1977, the two of them fulfilled a long-time dream by vacationing in Europe. When Gregory remarried in 1978, Mischa and Marguerite visited Canada with the new couple and welcomed three additional grandchildren into their family circle. The pleasure Mischa took in such activities, in friends and in Marguerite is reflected in an excerpt from a letter to Gregory. On Marguerite’s recreational eight-hand piano playing in their home, he wrote: "It’s not just the playing, but the company of good friends, and believe me, you hear as much laughter and honest-to-goodness giggles as you hear notes."

Until his sudden death from a heart attack late in 1979, Mischa continued to teach and to enjoy life, sharing his warmth, sense of humor and thoughtful care with those around him. Initially after his death, Marguerite remained in the family’s apartment and continued to teach. In the mid-1980s, she left New York and returned to Seattle to be nearer her son and family members, where she resided in a Jewish group residence. She continued to play privately with musician friends, giving occasional recitals for other residents, until her death at 94 years of age.[22]

Principal works

Chamber music: Berceuse (for cello and piano), 1933 Serenade (for violin and piano), 1933 Romance (for violin and piano), 1933 Quartet (for piano and strings), 1944

Solo piano music: Prelude Impressions and Fuga Libra,1934 (revised 1939) Marches for Tomorrow, 1943 Murals, 1943 Piano Sonata, 1944 Cancion Popular, 1947 Gavotte, 1947 Second Sonata, 1947 Nostalgia,1947 First Sonatina, 1948 Pastorale, 1948 Third Sonata, 1948 Variations on Hatikvah (undated)

Two-piano pieces: Four Children’s Pieces, 1935 Perpetual Motion on a Theme of Brahms, 1937 (also, possibly a solo piano version) Improvisation for Two Pianos after a Theme of K.P.E. Bach, 1937 Concerto Quasi Una Fantasia (Concerto for Two Pianos - unaccompanied), 1937 Four Pieces for Two Pianos, 1938 Rondino for Two Pianos, 1940 March of the Imps (undated) Brief Flirtation (undated Sentimental Parting (undated) Playful Leaves (undated) A Story My Music Box Told Me (undated)

Orchestral music: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, 1941 (revised 1946) Orchestral Accompaniment for Chopin’s Rondo for Two Pianos in C Major (written at the request of Pierre Luboshutz and Genia Nemenoff)

Theater: Incidental music for The Royal Blush, a Theater Guild adaptation of The Merry Wives of Windsor, an early vehicle for Jessie Royce Landis, Score for Happy as Larry, 1950; Burgess Meredith, director and lead actor Ballet for Bless You All, 1950; ballet sequence with Don Walker. (Piano score of ballet I Can Hear it Now may be found in the Library of Congress, Music Division, Special Collections, Don Walker Collection, Box 30, Folder 24.)

Films: Cheer Up! Smile! Nertz!, 1931. Lyrics by Norman Anthony, recorded by Eddie Cantor. 57th Street Rhapsody, 1947, for Carnegie Hall, Dir. E.G. Ulmer, United Artists.

References

- ↑ McNamara, Daniel (ed). 1952. ASCAP's Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers, 2nd ed. Thomas Y Crowell Co.

- ↑ Obituary, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y. Nov.8, 1940

- ↑ Personal correspondence collection, from Leo to Mischa

- ↑ Ewen, David (ed). 1949. American Composers Today: A Biographical and Critical Guide. New York: H.W. Wilson Co.

- ↑ N.S., "Duo-pianists give Town Hall recital: Composition by Mischa Portnoff is on program for its first hearing." New York Times, Nov.1, 1937. While for some reason identified by initials only, the reviewer was almost certainly Nicholas Slonimsky.

- ↑ Ewen, David (ed). American Composers Today: A Biographical and Critical Guide. New York: H.W. Wilson Co.

- ↑ Personal correspondence, cited in archival excerpt from article in Brooklyn Daily Eagle. N.Y., Feb.1, 1941. See https://www.newspapers.com/image/52673238.

- ↑ Personal correspondence, Barbirolli to Reisenberg, May 29, 1940; also see A. Tommasini, "Reopening a Pianist's Treasury of Chopin," in The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2009. http://nytimes/2009/01/05/arts/music/05nadi.html?_r=0.

- ↑ Sherman, Robert and Alexander Sherman. 1986 Nadia Reisenberg: A Musician's Scrapbook, first ed. International Archives.

- ↑ Frank Gallop, taped introduction to the February 23, 1941 radio broadcast of the Carnegie Hall premier of Portnoff's concerto. Columbia Broadcasting Co., New York.

- ↑ Downes, Olin 1941. Premier is Given by Philharmonic: First Performance of Mischa Portnoff's Piano Concerto Heard at Carnegie Hall." In The New York Times, Feb. 25

- ↑ Ewen, David (ed). 1949, American Composers Today: A Biographical and Critical Guide. New York: H.W. Wilson Co.

- ↑ Matthew-Walker, Robert. 2008. John Barbirolli/New York Philharmonic Orchestra, liner notes. Ottoxeter, England: Barbirolli Society.

- ↑ "Film's Rhapsody by Boro Brothers." In The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y. Oct. 10, 1947. See https://www.newspapers.com/image/52876013

- ↑ Portnoff, Mischa and Wesley, composers for the 1947 film Carnegie Hall, Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer. Bel Canto Society VHS, 1995; DVD, 2005.

- ↑ Cinderella Man, Director: Ron Howard, Universal Pictures, May 29, 2005.

- ↑ "Theater Notes" In The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y. Jan. 6, 1950. See https://www.newspapers.com/image/53780104

- ↑ Atkinson, Brooks. 1950. "At the Theatre: Burgess Meredith Appears in a Musical Fantasy Entitled 'Happy as Larry' at the Coronet." In The New York Times, Jan. 7.

- ↑ Saroyan, William. 1953. "Some Frank Talk from William Saroyan." In The New York Times, Jan. 4.

- ↑ Shaeffer, Louis. 1950. "Curtain Time" Coronet's 'Happy as Larry' and Unusual Sort of Musical" In The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 7.

- ↑ Obituary. 1979. In The New York Times, May 17.

- ↑ Ewen, David ed. 1949 American Composers Today: A Biographical and Critical Guide. New York: H.W. Wilson Co. Supplemented by interviews of Marguerite Portnoff and family documents.