Neutral Moresnet

| Neutral Moresnet | ||||||||||

| French: Moresnet Neutre German: Neutral-Moresnet Dutch: Neutraal-Moresnet Esperanto: Neŭtrala Moresneto | ||||||||||

| neutral zone | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

3 Neutral Moresnet

| ||||||||||

| Capital | Kelmis | |||||||||

| Languages | Esperanto · French · German · Dutch | |||||||||

| Government | Condominium | |||||||||

| Mayor | ||||||||||

| • | 1817–1859 | Arnold Timothée de Lasaulx | ||||||||

| • | 1918–1920 | Pierre Grignard | ||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Agreement of Aachen | June 26, 1816 | ||||||||

| • | Annexation by Belgium | January 10, 1920 | ||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||

| • | 1900 | 3.5 km² (1 sq mi) | ||||||||

| • | 1914 | 3.6 km² (1 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||

| • | 1900 est. | 3,000 | ||||||||

| Density | 857.1 /km² (2,220 /sq mi) | |||||||||

| • | 1914 est. | 3,500 | ||||||||

| Density | 972.2 /km² (2,518 /sq mi) | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| [1] | ||||||||||

Neutral Moresnet[2] [mɔ.ʁe.ne] was a small Belgian–Prussian condominium that existed from 1816 to 1920 between present-day Belgium and Germany. Its northernmost border point at the Vaalserberg connected it to a quadripoint shared additionally with the Dutch Province of Limburg, which today is known as Three‑Country Point. Prior to Belgian independence in 1830, the territory was a Dutch–Prussian condominium. During the First World War, the territory was annexed into Germany, although the allies did not recognise the annexation.

The former territory is now in the Belgian municipality of Kelmis. Today, it is especially of interest to Esperantists because of initiatives to found an Esperanto‑speaking state, named Amikejo (lit. "friendship place"), on the territory in the early 20th century.

History

Origins

After the demise of Napoleon's Empire, the Congress of Vienna of 1814/1815 redrew the European map, aiming at creating a balance of power. One of the borders to be delineated was the one between the newly founded United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Prussia. Both parties could agree on the larger part of the territory, as borders mostly followed older lines, but the district of Moresnet proved problematic, mainly because of the valuable zinc spar mine called Altenberg (German) or Vieille Montagne (French) located there. Both the Netherlands and Prussia were keen to appropriate this resource, which was needed in the production of zinc and brass—at that time, Bristol in England was the only other place where zinc ore was processed.[3]

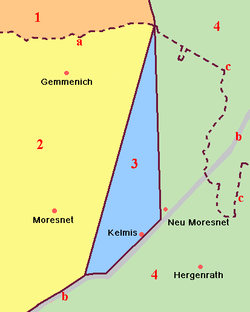

In December 1815, Dutch and Prussian representatives convened in nearby Aachen and on June 26, 1816 a compromise was reached, dividing the district of Moresnet into three parts. The village of Moresnet itself would become part of the Dutch province of Liège, whereas the Prussian village Moresnet (renamed Neu-Moresnet after World War I) would become part of the Prussian Rhine province, and the mine and the adjacent village—would become a neutral territory pending a future agreement. The two powers, both barred from occupying the area with their military, established a joint administration.

When Belgium gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1830, the Belgians took over the Dutch role in Neutral Moresnet (though formally the Dutch never ceded their claim).

Borders

Formal installation of border demarcation markers for the territory occurred on September 23, 1818. The territory of Neutral Moresnet had a somewhat triangular shape with the base being the main road from Aachen to Liège. The village and mine lay just to the north of this road. To east and west two straight lines converged on the Vaalserberg.

The roads from Germany and Belgium to Three‑Country Point are named Dreiländerweg (lit. Three Countries Way) and Route des Trois Bornes (lit. Three Boundary Stones Road) respectively; the road from the Netherlands is called Viergrenzenweg (lit. Four Boundaries Way).[4]

Flag

From 1883, Neutral Moresnet used a tricolore with horizontal bars in black, white and blue as its territorial flag. The origin is unclear and has been explained in two different ways:[5]

- Some hold that the colours were taken from the two conflicting powers' flags, with black and white standing for Prussia and white and blue for the Netherlands.

- According to Flags of the World, "it seems more likely that the colours have been taken from the emblem of the Vieille Montagne [mining company]".[6]

Status

The territory was governed by two royal commissioners, one from each neighbour. Eventually, these commissioners were commonly civil servants from the Belgian Verviers and the Prussian Eupen. The municipal administration was headed by a mayor appointed by the commissioners.

The Napoleonic civil and penal codes, introduced under French rule, remained in force throughout the existence of Neutral Moresnet. However, since no law court existed in the neutral territory, Belgian and Prussian judges had to come in and decide cases based on the Napoleonic laws. Since there was no administrative court either, the mayor's decision could not be appealed.

In 1859, Neutral Moresnet was granted a greater measure of self-administration by the installation of a municipal council of ten members. The council, as well as a welfare committee and a school committee, were appointed by the mayor and served an advisory function only. The people had no voting rights.[7]

Life in Neutral Moresnet was dominated by the Vieille Montagne mining company, which not only was the major employer but also operated residences, shops, a hospital and a bank. The mine attracted many workers from the neighboring countries, increasing the population from 256 in 1815 to 2,275 in 1858 and 4,668 in 1914. Most services such as the mail were shared between Belgium and Prussia (in a fashion similar to Andorra). There were five schools in the territory, and Prussian subjects could attend the schools in Prussian Moresnet.

Living in the territory had several benefits. Among these were the low taxes (the national budget being fixed at 2,735 fr. throughout its history), the absence of import tariffs from both neighbouring countries, and low prices compared to just across the border. A downside to their special status was the fact that people from Neutral Moresnet were considered to be stateless and were not allowed a military of their own. However, there is no record of Neutral Moresnet taking a hostile international stance.

Many immigrants settled in Moresnet so they would be exempt from military service, but in 1854 Belgium began to conscript its citizens who had moved to Moresnet, and Prussia did likewise in 1874. From then on, the exemption applied only to descendants of the original inhabitants.[8]

Currency

Neutral Moresnet did not have its own currency. The French franc was legal tender. The currencies of Prussia (and then Germany, after 1871), Belgium and the Netherlands were also in circulation. In 1848 local currency began circulating, though these coins were not considered the official medium.[9]

Uncertain future

When the mine was exhausted in 1885, doubts arose about the continued survival of Neutral Moresnet. Several ideas were put forward to establish the territory as a more independent entity:

In 1886, Dr. Wilhelm Molly (1838–1919), the mine's chief medical doctor and an avid philatelist, tried to organise a local postal service with its own stamps. This enterprise was quickly thwarted by Belgian intervention.[10]

A casino was established in August 1903 after Belgium had forced all such resorts to close. The Moresnet casino operated under strict limitations, permitting no local resident to gamble, and no more than 20 persons to gather at a time. The venture was abandoned, however, when Kaiser Wilhelm II threatened to partition the territory or cede it to Belgium in order to end the gambling. Around this same time, Moresnet boasted three distilleries for the manufacture of gin.[11]

The most remarkable initiative occurred in 1908, when Dr. Molly proposed making Neutral Moresnet the world's first Esperanto‑speaking state, named Amikejo ("place of friendship"). The proposed national anthem was an Esperanto march of the same name. A number of residents learned Esperanto and a rally was held in Kelmis in support of the idea of Amikejo on August 13, 1908. The World Congress of Esperanto, meeting in Dresden, even declared Neutral Moresnet the world capital of the Esperanto community.[10]

However, time was running out for the tiny territory. Neither Belgium nor Prussia (now within the German Empire) had ever surrendered its original claim to it. Around 1900, Germany in particular was taking a more aggressive stance towards the territory and was accused of sabotage and of obstructing the administrative process in order to force the issue.

First World War

The First World War brought about the end of neutrality. On August 4, 1914, Germany invaded Belgium, leaving Moresnet at first "an oasis in a desert of destruction".[12] In 1915, the territory was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, without international recognition.

In 1918, the Armistice between France and Germany, signed on November 11 at Compiègne, forced Germany to withdraw from Belgium and also from Moresnet.

On June 28, 1919, the Treaty of Versailles settled the dispute that had created the neutral territory a century earlier by awarding Neutral Moresnet, along with Prussian Moresnet and the German municipalities of Eupen and Malmedy, to Belgium,[13] thus permanently ending the status of a neutral territory.

Post-war history

The territory was formally annexed by Belgium on January 10, 1920. To distinguish it from the already existing town of Moresnet (in the neighboring municipality of Plombières), Neutral Moresnet was renamed Kelmis (in French: La Calamine) – after kelme, the local dialect word for zinc spar – while Prussian Moresnet was renamed Neu‑Moresnet (New Moresnet).

After 1920, Moresnet shared the history of Eupen and Malmedy.[14] Germany briefly re‑annexed the area during World War II, but it returned to Belgium in 1944. Since 1973, Kelmis has formed a part of the German‑speaking community of Belgium. In 1977, Kelmis absorbed the neighbouring communes of Neu‑Moresnet and Hergenrath.

A small museum in Neu‑Moresnet, the Göhltal Museum (French: Musée de la Vallée de la Gueule), includes exhibits on Neutral Moresnet. Of the 60 border markers for the territory, more than 50 are still standing.[15]

As a company, Vieille Montagne survived Neutral Moresnet. It branched out and after two centuries continues to exist as VMZINC, a part of Union Minière, the latter renamed in 2001 as Umicore, a global materials company.[3]

Dutch newspaper Trouw reported in November 2016 there was still one survivor left of the former territory, after the death of Alwine Hackens-Paffen (19 October 1913 - 26 October 2016). Mrs. Hackens' death left Catharina Meessen as the last remaining person to be born in Neutral Moresnet.[16]

Famous people

- Emil Dovifat (1890–1969), German scholar of journalism

- Bart Vreeken (1901–1988), Dutch zoologist

- Paul Verbeek (1875–1941), Dutch theologian

List of executive officers

List of Royal Commissioners

| Name | Term | Notes | Name | Term | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appointed by the United Kingdom of the Netherlands: | Appointed by the Kingdom of Prussia: | ||||

| Werner Jacob | December 8, 1817 – December 2, 1823 | lawyer | Wilhelm Hardt | August 6, 1817 – 1819 | Mining consultant |

| Johann Martin Daniel Mayer | April 22, 1819 – March 1836 |

Mining consultant | |||

| Joseph Brandès | December 2, 1823 – 1830 | School inspector | |||

| Vacancy due to the Belgian Revolution, followed by Royal Commissioners appointed by the Kingdom of Belgium: | |||||

| Lambert Ernst | June 8, 1835 – 1840 | Deputy Prosecutor, Court of Appeal in Liège | |||

| Heinrich Martins | July 9, 1836 – November 9, 1853 or 1854 | Mining consultant | |||

| Mathieu Crémer | February 1, 1840 – 1889 | Judge from Verviers | |||

| Peter Benedict Joseph Amand von Harenne | August 11, 1852 or 1854 – January 7, 1866 | District commissioner of Eupen | |||

| Freiherr von der Heydt | December 12, 1866 – 1868 | Former district commissioner of Eupen | |||

| Edward Gülcher | 1868–1871 | District commissioner of Eupen | |||

| Alfred Theodor Sternickel | June 18, 1871 – April 1893 |

District commissioner of Eupen | |||

| Fernand Jacques Bleyfuesz | November 30, 1889 – March 27, 1915 | District commissioner of Verviers | |||

| Alfred Jakob Bernhard Theodor Gülcher | April 18, 1893 – January 1, 1909 |

District commissioner of Eupen | |||

| Walter Karl Maria The Losen | January 13, 1909 – November 1, 1918 | District commissioner of Eupen | |||

| De facto end of Belgian control due to German military occupation on August 4, 1914 | |||||

| Dr. Bayer (acting) | March 27 – June 27, 1915 |

Civil commissioner of Verviers | |||

| Annexed by Prussia in 1915, without international recognition | |||||

| Fernand Jacques Bleyfuesz | November 1918 – January 10, 1920 | District commissioner of Verviers | Vacancy due to the Armistice of 1918 | ||

List of mayors

| Name | Term |

|---|---|

| Arnold Timothée de Lasaulx | 1817 – February 2, 1859 |

| Adolf Hubert van Scherpenzeel-Thim | February 2 – May 30, 1859 |

| Joseph Kohl | June 1, 1859 – February 3, 1882 |

| Vacancy 1882–1885 | |

| Hubert Schmetz | June 20, 1885 – March 15, 1915 |

| Wilhelm Kyll | March 29, 1915 – December 7, 1918 |

| Pierre Grignard | December 7, 1918 – January 10, 1920 |

See also

References

- ↑ Martin, Lawrence; Reed, John (2006). The Treaties of Peace, 1919–1923. 1. Lawbook Exchange. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-58477-708-3. LCCN 2006005097.

Neutral Moresnet, added to this map as an independent country, is a mile [1.6 km] wide and 3 miles [4.8 km] long. It is so small that it has never been shown on maps of Europe as a whole. It has an area of 900 acres [360 ha] and about 3500 people . . .

- ↑ "The Moresnet Republic; Belgium Expects the District to Revert to Her" The New York Times, September 20, 1903, p. 5.

- 1 2 "VMZINC : un leadership enraciné dans l'histoire". Qui sommes nous? (in French). VMZINC. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Route 4: Landgraben" (PDF) (in French). GrenzRouten. 2009. pp. 45–46, 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2016.

- ↑ Neutral-Moresnet: History

- ↑ Sache, Ivan; Sensen, Mark (May 1, 2005). "The Neutral Territory of Moresnet (1816–1918)". Flags of the World. OCLC 39626054. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- ↑ Robert Shackleton, Unvisited Places of Old Europe, 1914, p. 161.

- ↑ Charles Hoch, The Neutral Territory of Moresnet, trans. William Warren Tucker, 1882, p. 13.

- ↑ Damen, Cees. "Coins". Neutral Moresnet. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- 1 2 Hoffmann, Eduard; Nendza, Jürgen (September 19, 2003). "Galmei und Esperanto, der fast vergessene europäische Kleinstaat Neutral‑Moresnet" (PDF) (in German). Südwestrundfunk. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Awaiting a Crisis in Belgium". The New York Times. September 13, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2016.

- ↑ Musgrave, George Clarke (1918). "The Belgian Prelude". Under Four Flags for France. New York: D. Appleton & Company. p. 8. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t8qb9xr4b. LCCN 18003816. OCLC 1157994. OL 7209571M.

As a proof of German preparation, war had come automatically at 7 a.m., August 3 [1914]. At 23 o’clock (Belgian time) the outposts on the main roads holding Pepinster, Battice, Herve and smaller hamlets, were heavily engaged and finally forced back to the fortified lines of [Liège]. The pretty towns defended near the frontier were soon flaming ruins, the quaint neutral territory of Moresnet rising as an oasis in a desert of destruction.

- ↑ Peace Treaty of Versailles Articles 32–33

- ↑ Wenselaers, Selm (2008). De laatste Belgen, een geschiedenis van de oostkantons (The last Belgians, a history of the eastern districts). Meulenhoff/Manteau. ISBN 978-90-8542-149-8.

- ↑ Berns, Eef (2002). "In search of the bordermarkers of Moresnet". Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ↑ Kuiken, Alwin (5 November 2016). "Dwergstaatje Neutraal Moresnet heeft nog slechts één oud-bewoner". Trouw (in Dutch).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neutral Moresnet. |

- Neutral Moresnet

- "Moresnet, Belgium". Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Pictures of the old mines

- Official website Kelmis (in German)

- Göhltalmuseum, a local museum that shows the history of Neutral Moresnet and its zinc mining (in German)

- Anarchy in the Aachen (Mises.org)

- Het vergeten land van Moresnet, documentary, 1990 (48', languages spoken: Dutch, German, French, Esperanto)

Coordinates: 50°43′49″N 6°00′48″E / 50.73028°N 6.01333°E