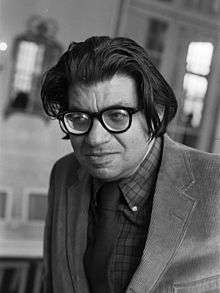

Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer.

A major figure in 20th-century music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School of composers also including John Cage, Christian Wolff, and Earle Brown. Feldman's works are characterized by notational innovations that he developed to create his characteristic sound: rhythms that seem to be free and floating; pitch shadings that seem softly unfocused; a generally quiet and slowly evolving music; recurring asymmetric patterns. His later works, after 1977, also begin to explore extremes of duration.

Biography

Feldman was born in Woodside, Queens into a family of Russian-Jewish immigrants from Kiev. His father was a manufacturer of children's coats.[1][2] As a child he studied piano with Vera Maurina Press, who, according to the composer himself, instilled in him a "vibrant musicality rather than musicianship."[3] Feldman's first composition teachers were Wallingford Riegger, one of the first American followers of Arnold Schoenberg, and Stefan Wolpe, a German-born Jewish composer who studied under Franz Schreker and Anton Webern. Feldman and Wolpe spent most of their time simply talking about music and art.[4]

In early 1950 Feldman went to hear the New York Philharmonic give a performance of Anton Webern's Symphony, op. 21. After this work, the orchestra was going to perform a piece by Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Feldman left immediately before that, disturbed by the audience's disrespectful reaction to Webern's work.[5] In the lobby he met John Cage, who was at the concert and had also decided to step out.[6] The two composers quickly became good friends, with Feldman moving into the apartment on the second floor of the building Cage lived in. Through Cage, he met sculptor Richard Lippold (who had a studio next door) and artists Sonia Sekula, Robert Rauschenberg, and others, and composers such as Henry Cowell, Virgil Thomson, and George Antheil.[7]

With encouragement from Cage, Feldman began to write pieces that had no relation to compositional systems of the past, such as the constraints of traditional harmony or the serial technique. He experimented with non-standard systems of musical notation, often using grids in his scores, and specifying how many notes should be played at a certain time, but not which ones. Feldman's experiments with the use of chance in his composition in turn inspired John Cage to write pieces like the Music of Changes, where the notes to be played are determined by consulting the I Ching.

Through Cage, Feldman met many other prominent figures in the New York arts scene, among them Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston and Frank O'Hara. He found inspiration in the paintings of the abstract expressionists,[8] and throughout the 1970s wrote a number of pieces around twenty minutes in length, including Rothko Chapel (1971, written for the building of the same name, which houses paintings by Mark Rothko) and For Frank O'Hara (1973). In 1977, he wrote the opera Neither[9] with original text by Samuel Beckett.

Feldman was commissioned to compose the score for Jack Garfein's 1961 film, Something Wild. However, after hearing the music for the opening scene, in which a character (played by Carroll Baker, incidentally also Garfein's wife) is raped, the director promptly withdrew his commission, opting to enlist Aaron Copland instead. The reaction of the startled director was said to be, "My wife is being raped and you write celesta music?"[10]

Morton Feldman's music "changed radically"[11] in 1970: moving away from his interest in graphic notation and arhythmic notation systems and toward a more rhythmically precise method of composition. The first piece of this new period was a short, fifty-five measure work entitled "Madame Press Died Last Week at Ninety", dedicated to his childhood piano teacher, Vera Maurina Press.

In 1973, at the age of 47, Feldman became the Edgard Varèse Professor (a title of his own devising) at the University at Buffalo. Prior to that time, Feldman had earned his living as a full-time employee at the family textile business in New York's garment district. In addition to teaching at SUNY Buffalo, Feldman also held residences during the mid-1980s at the University of California, San Diego.

Later, he began to produce his very long works, often in one continuous movement, rarely shorter than half an hour in length and often much longer. These works include Violin and String Quartet (1985, around 2 hours), For Philip Guston (1984, around four hours) and, most extreme, the String Quartet II (1983, which is over six hours long without a break.) Typically, these pieces maintain a very slow developmental pace (if not static) and tend to be made up of mostly very quiet sounds. Feldman said himself that quiet sounds had begun to be the only ones that interested him. In a 1982 lecture, Feldman noted: "Do we have anything in music for example that really wipes everything out? That just cleans everything away?"

Feldman married the Canadian composer Barbara Monk shortly before his death. He died from pancreatic cancer in 1987 at his home in Buffalo, New York, after fighting for his life for three months.

Works

Notable students

Footnotes

- ↑ Ross 2006.

- ↑ Hirata 2002, 131.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1985, 36.

- ↑ Gagne, Caras 1982.

- ↑ Feldman, Morton. "Liner Notes." Give My Regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman. Ed. B. H. Friedman. Cambridge: Exact Change, 2000. 4. Print.

- ↑ Revill 1993, 101.

- ↑ Feldman 1968.

- ↑ Vigeland, Nils. "Morton Feldman: The Viola in my Life". Liner note essay. New World Records.

- ↑ Ruch, A, Morton Feldman's Neither themodernword.com website, 17 May 2001. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter Niklas. "Canvasses and time canvasses". Chris Villars Homepage. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ Feldman, Morton (February 2, 1973). "Morton Feldman Slee Lecture, February 2, 1973". State University of New York at Buffalo. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

References

- Feldman, Morton. 1968. Give My Regards to Eighth Street, Artnews Annual. Included in Give my regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman (2000), The Music of Morton Feldman, and elsewhere.

- Gagne, Cole, and Caras, Tracey. 1982. Interview with Morton Feldman. In: Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers, 164–177. Metuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press Inc, 1982. Available online.

- Hirata, Catherin. 2002. Morton Feldman. In: Sitsky, Larry, ed. 2002. Music of the Twentieth-century Avant-garde. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Revill, David. 1993. The Roaring Silence: John Cage – a Life. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-220-6, ISBN 978-1-55970-220-1.

- Ross, Alex. 2006. American Sublime. The New Yorker, June 19, 2006. Available online.

- Zimmerman, Walter, ed. 1985. Morton Feldman Essays. Kerpen: Beginner.

Further reading

- Cline, David. The Graph Music of Morton Feldman. Cambridge University Press, 2016

- Eldred, Michael The Quivering of Propriation: A Parallel Way to Music, Section II.4.4 A musical subversion of harmonically logical time (Feldman) www.arte-fact.org 2010

- Feldman, Morton. Morton Feldman Says. Chris Villars, ed. London: Hyphen Press, 2006.

- Feldman, Morton. Morton Feldman in Middelburg. Lectures and Conversations. R. Mörchen, ed. Cologne: MusikTexte, 2008.

- Feldman, Morton. Give my regards to Eighth Street: Collected Writings of Morton Feldman. B.H. Friedman, ed. Cambridge, MA: Exact Change, 2000.

- Gareau, Philip. La musique de Morton Feldman ou le temps en liberté. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2006.

- Hirata, Catherin (Winter 1996). "The Sounds of the Sounds Themselves: Analyzing the Early Music of Morton Feldman", Perspectives of New Music 34, no.1, 6-27.

- Herzfeld, Gregor. "Historisches Bewusstsein in Morton Feldmans Unterrichtsskizzen", Archiv für Musikwissenschaft Vol. 66, no. 3, (Summer 2009), 218-233.

- Lunberry, Clark. "Departing Landscapes: Morton Feldman's String Quartet II and Triadic Memories." SubStance 110: Vol. 35, Number 2 (Summer 2006): 17-50. (Available at http://www.cnvill.net/mftexts.htm [#105 on the list])

- Noble, Alistair. Composing Ambiguity: The Early Music of Morton Feldman. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4094-5164-8

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Morton Feldman |

- Morton Feldman Page

- Morton Feldman Photographs, 1939-1987 from University at Buffalo Libraries

- Jan Williams Photos of Morton Feldman, 1974-1979 from University at Buffalo Libraries

- Morton Feldman in conversation with Thomas Moore

- Morton Feldman: Structures for String Quartet (1951) by Lejaren Hiller

- GregSandow.com: Feldman Draws Blood Village Voice, June 16, 1980

- Morton Feldman profile at New Albion Records

- Morton Feldman at Pytheas Center for Contemporary Music

- "biography" (in French). IRCAM.

Listening

- Art of the States: Morton Feldman three works by the composer

- UbuWeb: Morton Feldman featuring The King of Denmark

- Epitonic.com: Morton Feldman featuring tracks from Only – Works for Voice and Instruments

- In Conversation with John Cage, 1966, Part 1

- In Conversation with John Cage, 1966, Part 2

- In Conversation with John Cage, 1966, Part 3

- In Conversation with John Cage, 1966, Part 4

- In Conversation with John Cage, 1966, Part 5